Malawi

Republic of Malawi | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Unity and Freedom" | |

| Anthem: Mlungu dalitsani Malaŵi (Chichewa) (English: "O God Bless Our Land of Malawi")[1] | |

Location of Malawi (dark green) in southeast Africa | |

| Capital and largest city | Lilongwe 13°57′S 33°42′E / 13.950°S 33.700°E |

| Official languages | |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2018 census[2]) | |

| Religion (2018 census)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Malawian |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Lazarus Chakwera | |

| Michael Usi | |

| Catherine Gotani Hara | |

| Rizine Mzikamanda | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

• Dominion | 6 July 1964 |

• Republic | 6 July 1966 |

| Area | |

• Total | 118,484 km2 (45,747 sq mi) (98th) |

• Water (%) | 20.6% |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• 2018 census | 17,563,749[2] |

• Density | 153.1/km2 (396.5/sq mi) (56th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2016) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | low (172nd) |

| Currency | Malawian kwacha (D) (MWK) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Drives on | Left |

| Calling code | +265[8] |

| ISO 3166 code | MW |

| Internet TLD | .mw[8] |

* Population estimates for this country explicitly take into account the effects of excess mortality due to AIDS; this can result in lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality and death rates, lower population and growth rates, and changes in the distribution of population by age and sex than would otherwise be expected.

| |

Malawi (/məˈlɑːwi/; lit. 'flames' in Chichewa and Chitumbuka),[9] officially the Republic of Malawi and formerly known as Nyasaland, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest. Malawi spans over 118,484 km2 (45,747 sq mi) and has an estimated population of 21,240,689 (as of 2024).[10] Malawi's capital and largest city is Lilongwe. Its second-largest is Blantyre, its third-largest is Mzuzu, and its fourth-largest is Zomba, the former capital.

The part of Africa now known as Malawi was settled around the 10th century by migrating Bantu groups. They formed various kingdoms such as Maravi kingdom and Nkhamanga Kingdom, among others that flourished from the 16th century.[11][12] In 1891, the area was colonised by the British as the British Central African Protectorate, and it was renamed Nyasaland in 1907. In 1964, Nyasaland became an independent country as a Commonwealth realm under Prime Minister Hastings Banda, and was renamed Malawi. Two years later, Banda became president by converting the country into a one-party presidential republic. Banda was declared President for life in 1971. Independence were characterized by Banda's highly repressive dictatorship.[13][14][15] After the introduction of a multiparty system in 1993, Banda lost the 1994 general election. Today, Malawi has a democratic, multi-party republic headed by an elected president. According to the 2024 V-Dem Democracy indices, Malawi is ranked 74th electoral democracy worldwide and 11th electoral democracy in Africa.[16] The country maintains positive diplomatic relations with most countries, and participates in several international organisations, including the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), and the African Union (AU).

Malawi is one of the world's least-developed countries. The economy is heavily based on agriculture, and it has a largely rural and growing population. Key indicators of progress in the economy, education, and healthcare were seen in 2007 and 2008.

Malawi has a low life expectancy and high infant mortality. HIV/AIDS is highly prevalent, which both reduces the labour force and requires increased government expenditures. The country has a diverse population that includes native peoples, Asians, and Europeans. Several languages are spoken, and there is an array of religious beliefs. Although in the past there was a periodic regional conflict fuelled in part by ethnic divisions, by 2008 this internal conflict had considerably diminished, and the idea of identifying with one's Malawian nationality had reemerged.

Etymology

[edit]The first name given to what is known now as Malawi was Nyasaland, a combination of the Yao word nyasa "lake" and the English word "land". The combined name was formed by David Livingstone, a Scottish explorer and missionary who led the Zambezi Expedition through the area in the mid-1800s.[17] The current name Malawi, meaning "flames" in Chichewa and Chitumbuka, was chosen by the first president of Malawi, Kamuzu Banda, after the country achieved its independence from Great Britain in 1964.[18][19]

History

[edit]Pre-colonial history

[edit]

The area of Africa now known as Malawi had a very small population of hunter-gatherers before waves of Bantu peoples began emigrating from the north around the 10th century CE.[20] Although most of the Bantu peoples continued south, some remained and founded ethnic groups based on common ancestry.[21] By 1500, the tribes had established several kingdoms such as the Maravi that reached from north of what is now Nkhotakota to the Zambezi River and from Lake Malawi to the Luangwa River in what is now Zambia and the Nkhamanga.[22]

Soon after 1600, with the area mostly united under one native ruler, native tribesmen began encountering, trading with and making alliances with Portuguese traders and members of the military. By 1700, however, the empire had broken up into areas controlled by many individual ethnic groups.[23] The Indian Ocean slave trade reached its height in the mid-1800s, when approximately 20,000 people per year were believed to have been enslaved and transported from Nkhotakota to Kilwa where they were sold.[24]

Colonialisation (1859–1960)

[edit]Missionary and explorer David Livingstone reached Lake Malawi (then Lake Nyasa) in 1859 and identified the Shire Highlands south of the lake as an area suitable for European settlement. As the result of Livingstone's visit, several Anglican and Presbyterian missions were established in the area in the 1860s and 1870s; the African Lakes Company Limited was established in 1878 to set up a trade and transport concern, a small mission and trading settlement were established at Blantyre in 1876, and a British Consul took up residence there in 1883. The Portuguese government was also interested in the area, so, to prevent Portuguese occupation, the British government sent Harry Johnston as British consul with instructions to make treaties with local rulers beyond Portuguese jurisdiction.[25]

In 1889, a British protectorate was proclaimed over the Shire Highlands, which was extended in 1891 to include the whole of present-day Malawi as the British Central Africa Protectorate.[26] In 1907, the protectorate was renamed Nyasaland, a name it retained for the remainder of its time under British rule.[27] In an example of what is sometimes called the "Thin White Line" of colonial authority in Africa, the colonial government of Nyasaland was formed in 1891. The administrators were given a budget of £10,000 (1891 nominal value) per year, which was enough to employ ten European civilians, two military officers, seventy Punjabi Sikhs and eighty-five Zanzibar porters. These few employees were then expected to administer and police a territory of around 94,000 square kilometres with between one and two million people.[28] That same year, slavery came to its complete cessation.

In 1944, the Nyasaland African Congress (NAC) was formed by the Africans of Nyasaland to promote local interests to the British government.[29] In 1953, Britain linked Nyasaland with Northern and Southern Rhodesia in what was the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, often called the Central African Federation (CAF),[27] for mainly political reasons.[30] Even though the Federation was semi-independent, the linking provoked opposition from African nationalists, and the NAC gained popular support. An influential opponent of the CAF was Hastings Banda, a European-trained doctor working in Ghana who was persuaded to return to Nyasaland in 1958 to assist the nationalist cause. Banda was elected president of the NAC and worked to mobilize nationalist sentiment before being jailed by colonial authorities in 1959. He was released in 1960 and asked to help draft a new constitution for Nyasaland, with a clause granting Africans the majority in the colony's Legislative Council.[21]

Hastings Kamuzu Banda era (1961–1993)

[edit]

In 1961, Banda's Malawi Congress Party (MCP) gained a majority in the Legislative Council elections, and Banda became Prime Minister in 1963. The Federation was dissolved in 1963, and on 6 July 1964, Nyasaland became independent from British rule and renamed itself Malawi, and that is commemorated as the nation's Independence Day, a public holiday.[31] Under a new constitution, Malawi became a republic with Banda as its first president. The new document also formally made Malawi a one-party state with the MCP as the only legal party.

In 1971, Banda was declared president-for-life. For almost 30 years, Banda presided over a rigidly totalitarian regime, which ensured that Malawi did not suffer armed conflict.[32] Opposition parties, including the Malawi Freedom Movement of Orton Chirwa and the Socialist League of Malawi, were founded in exile. Malawi's economy, while Banda was president, was often cited as an example of how a poor, landlocked, and heavily populated country deficient in mineral resources could achieve progress in both agriculture and industrial development.[33]

Multi-party democracy (1993–present)

[edit]Under pressure for increased political freedom, Banda agreed to a referendum in 1993, where the populace voted for a multi-party democracy. In late 1993, a presidential council was formed, the life presidency was abolished and a new constitution was put into place, effectively ending the MCP's rule.[32] In 1994 the first multi-party elections were held in Malawi, and Banda was defeated by Bakili Muluzi (a former Secretary General of the MCP and former Banda Cabinet Minister). Re-elected in 1999, Muluzi remained president until 2004, when Bingu wa Mutharika was elected.[34] Although the political environment was described as "challenging", it was stated in 2009 that a multi-party system still existed in Malawi.[35] Multiparty parliamentary and presidential elections were held for the fourth time in Malawi in May 2009, and President Mutharika was successfully re-elected, despite charges of election fraud from his rival.[36]

President Mutharika was seen by some as increasingly autocratic and dismissive of human rights,[37] and in July 2011 protests over high costs of living, devolving foreign relations, poor governance and a lack of foreign exchange reserves erupted.[38] The protests left 18 people dead and at least 44 others suffering from gunshot wounds.[39]

The Malawian flag was modified in 2010, altering three colored stripes with the white sun. It existed for a short while until 2012 when the colors of black-red-green of the old flag were restored.

In April 2012, Mutharika died of a heart attack. Over a period of 48 hours, his death was kept secret, including an elaborate flight with the body to South Africa, where the ambulance drivers refused to move the body, saying they were not licensed to move a corpse.[40] After the South African government threatened to reveal the information, the presidential title was taken over by Vice-President Joyce Banda[41] (no relation to Hastings Banda).[42]

In the 2014 Malawian general election, Joyce Banda lost the elections (coming third) and was replaced by Peter Mutharika, the brother of ex-President Mutharika.[43] In the 2019 Malawian general election president Peter Mutharika was narrowly re-elected. In February 2020 Malawi Constitutional Court overturned the result because of irregularities and widespread fraud.[44] In May 2020 Malawi Supreme Court upheld the decision and announced a new election was held on July 2. This was the first time an election in the country was legally challenged.[45][46] Opposition leader Lazarus Chakwera won the 2020 Malawian presidential election and he was sworn in as the new president of Malawi.[47]

Government and politics

[edit]Malawi is a unitary presidential republic under the leadership of President Lazarus Chakwera.[48] The current constitution was put into place on 18 May 1995. The branches of the government consist of executive, legislative, and judicial. The executive includes a President who is both Head of State and Head of Government, first and second Vice Presidents, and the Cabinet of Malawi. The President and Vice President are elected together every five years. A second Vice President may be appointed by the President if so chosen, although they must be from a different party. The members of the Cabinet of Malawi are appointed by the President and can be from either inside or outside of the legislature.[22]

The legislative branch consists of a unicameral National Assembly of 193 members who are elected every five years,[49] and although the Malawian constitution provides for a Senate of 80 seats, one does not exist in practice. If created, the Senate would provide representation for traditional leaders and a variety of geographic districts, as well as special interest groups, including the disabled, youth, and women. The Malawi Congress Party is the ruling party together with several other parties in the Tonse Alliance led by Lazarus Chakwera while the Democratic Progressive Party is the main opposition party. Suffrage is universal at 18 years of age, and the central government budget for 2021/2022 is $2.4 billion from $2.8 billion for the 2020/2021 financial year.[22][50]

The independent judicial branch is based upon the English model and consists of a Supreme Court of Appeal, a High Court divided into three sections (general, constitutional, and commercial), an Industrial Relations Court and Magistrates Courts, the last of which is divided into five grades and includes Child Justice Courts.[51] The judicial system has been changed several times since Malawi gained independence in 1964. Conventional courts and traditional courts have been used in varying combinations, with varying degrees of success and corruption.[52]

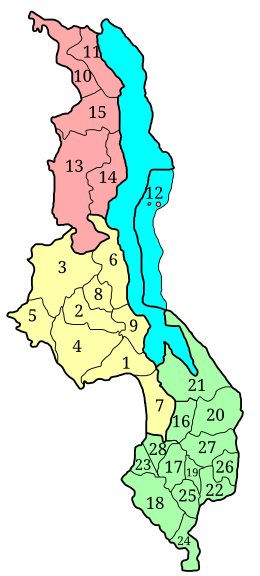

Malawi is composed of three regions (the Northern, Central, and Southern regions),[53] which are divided into 28 districts,[54] and further into approximately 250 traditional authorities and 110 administrative wards.[53] Local government is administered by central government-appointed regional administrators and district commissioners. For the first time in the multi-party era, local elections took place on 21 November 2000, with the UDF party winning 70% of the available seats. There was scheduled to be a second round of constitutionally mandated local elections in May 2005, but these were cancelled by the government.[22]

In February 2005, President Mutharika split with the United Democratic Front and began his own party, the Democratic Progressive Party, which had attracted reform-minded officials from other parties and won by-elections across the country in 2006. In 2008, President Mutharika had implemented reforms to address the country's major corruption problem, with at least five senior UDF party members facing criminal charges.[55]

In 2012, Malawi was ranked 7th of all countries in sub-Saharan Africa in the Ibrahim Index of African Governance, an index that measures several variables. Although the country's governance score was higher than the continental average, it was lower than the regional average for southern Africa. Its highest scores were for safety and rule of law, and its lowest scores were for sustainable economic opportunity, with a ranking of 47th on the continent for educational opportunities. Malawi's governance score had improved between 2000 and 2011.[56] Malawi held elections in May 2019, with President Peter Mutharika winning re-election over challengers Lazarus Chakwera, Atupele Muluzi, and Saulos Chilima.[57] In 2020 Malawi Constitutional Court annulled President Peter Mutharika's narrow election victory last year because of widespread fraud and irregularities. Opposition leader Lazarus Chakwera won the 2020 Malawian presidential election and he became the new president.[58]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Malawi is divided into 28 districts within three regions:

|

|

|

|

Foreign relations

[edit]Former President Hastings Banda established a pro-Western foreign policy that continued into early 2011. It included good diplomatic relationships with many Western countries. The transition from a one-party state to a multi-party democracy strengthened Malawian ties with the United States. Significant numbers of students from Malawi travel to the US for schooling, and the US has active branches of the Peace Corps, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human Services, and the Agency for International Development in Malawi.

Malawi maintained close relations with South Africa throughout the Apartheid era, which strained Malawi's relationships with other African countries. Following the collapse of apartheid in 1994, diplomatic relationships were made and maintained into 2011 between Malawi and all other African countries. In 2010, however, Malawi's relationship with Mozambique became strained, partially due to disputes over the use of the Zambezi River and an inter-country electrical grid.[22] In 2007, Malawi established diplomatic ties with China, and Chinese investment in the country has continued to increase since then, despite concerns regarding the treatment of workers by Chinese companies and competition of Chinese business with local companies.[59] In 2011, a document was released in which the British ambassador to Malawi criticised President Mutharika. Mutharika expelled the ambassador from Malawi, and in July 2011, the UK announced that it was suspending all budgetary aid because of Mutharika's lack of response to criticisms of his government and economic mismanagement.[60] On 26 July 2011, the United States followed suit, freezing a US$350 million grant, citing concerns regarding the government's suppression and intimidation of demonstrators and civic groups, as well as restriction of the press and police violence.[61]

Malawi has been seen as a haven for refugees from other African countries, including Mozambique and Rwanda, since 1985. These influxes of refugees have placed a strain on the Malawian economy but have also drawn significant inflows of aid from other countries. Donors to Malawi include the United States, Canada, and Germany, as well as international institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the European Union, the African Development Bank, and UN organizations. Malawi is a member of several international organizations, including the Commonwealth, the UN and some of its child agencies, the IMF, the World Bank, the African Union, and the World Health Organization. The country was the first in southern Africa to receive peacekeeping training under the African Crisis Response Initiative.[22]

Malawi is the 79th most peaceful country in the world (of 163), according to the 2024 Global Peace Index.[62]

Human rights

[edit]As of 2017[update], international observers noted issues in several human rights areas. Excessive force was seen to be used by police forces and security forces with impunity, mob violence was occasionally seen, and prison conditions continued to be harsh and sometimes life-threatening. However, the government was seen to make some effort to prosecute security forces who used excessive force. Other legal issues included limits on free speech and freedom of the press, lengthy pretrial detentions, and arbitrary arrests and detentions. Corruption within the government is seen as a major issue, despite the Malawi Anti-Corruption Bureau's (ACB) attempts to reduce it. Corruption within security forces is also an issue.[63] Malawi had one of the highest rates of child marriage in the world.[64] In 2015, Malawi raised the legal age for marriage from 15 to 18.[65]

Societal issues found included violence against women, human trafficking, and child labour. Other issues that have been raised are lack of adequate legal protection of women from sexual abuse and harassment, very high maternal mortality rate, and abuse related to accusations of witchcraft.[66][67][68] As of 2010[update], homosexuality has been illegal in Malawi. In one 2010 case, a couple perceived as homosexual (a man and a trans woman) faced extensive jail time when convicted.[69] The convicted pair, sentenced to the maximum of 14 years of hard labour each, were pardoned two weeks later following the intervention of United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon.[70] In May 2012, then-President Joyce Banda pledged to repeal laws criminalising homosexuality.[71] It was her successor, Peter Mutharika, who imposed a moratorium in 2015 that suspended the country's anti-gay laws pending further review of the same laws.[72][73] On 26 June 2021, the country's LGBT community held the first Pride parade in Lilongwe.[72]

Geography

[edit]

Malawi is a landlocked country in southeastern Africa, bordered by Zambia to the northwest, Tanzania to the northeast, and Mozambique to the south, southwest, and southeast. It lies between latitudes 9° and 18°S, and longitudes 32° and 36°E. The Great Rift Valley runs through the country from north to south, and to the east of the valley lies Lake Malawi (also called Lake Nyasa), making up over three-quarters of Malawi's eastern boundary.[21] Lake Malawi is sometimes called the Calendar Lake as it is about 365 miles (587 km) long and 52 miles (84 km) wide.[74] The Shire River flows from the south end of the lake and joins the Zambezi River 400 kilometres (250 mi) farther south in Mozambique. The surface of Lake Malawi is at 457 metres (1,500 ft) above sea level, with a maximum depth of 701 metres (2,300 ft), which means the lake bottom is over 213 metres (700 ft) below sea level at some points.[75]

In the mountainous sections of Malawi surrounding the Rift Valley, plateaus rise generally 914 to 1,219 metres (3,000 to 4,000 ft) above sea level, although some rise as high as 2,438 metres (8,000 ft) in the north. To the south of Lake Malawi lies the Shire Highlands, gently rolling land at approximately 914 metres (3,000 ft) above sea level. In this area, the Zomba and Mulanje mountain peaks rise to respective heights of 2,134 and 3,048 metres (7,000 and 10,000 ft).[21]

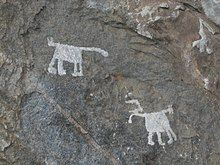

Malawi's capital is Lilongwe, and its commercial centre is Blantyre, with a population of over 500,000 people.[21] Malawi has two sites listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Lake Malawi National Park was first listed in 1984, and the Chongoni Rock Art Area was listed in 2006.[76]

Malawi's climate is hot in the low-lying areas in the south of the country and temperate in the northern highlands. The altitude moderates what would otherwise be an equatorial climate. Between November and April, the temperature is warm with equatorial rains and thunderstorms, with the storms reaching their peak severity in late March. After March, the rainfall rapidly diminishes, and from May to September, wet mists float from the highlands into the plateaus, with almost no rainfall during these months.[21]

Flora and fauna

[edit]

Animal life indigenous to Malawi includes mammals such as elephants, hippos, antelopes, buffaloes, big cats, monkeys, rhinos, and bats; a great variety of birds, including birds of prey, parrots, and falcons; waterfowl and large waders; and owls and songbirds. Lake Malawi has been described as having one of the richest lake fish faunas in the world, being the home for some 200 mammals, 650 birds, 30+ mollusk, and 5,500+ plant species.[77]

Seven terrestrial ecoregions lie within Malawi's borders: Central Zambezian miombo woodlands, Eastern miombo woodlands, Southern miombo woodlands, Zambezian and mopane woodlands, Zambezian flooded grasslands, South Malawi montane forest-grassland mosaic, and Southern Rift montane forest-grassland mosaic.[78] There are five national parks, four wildlife and game reserves and two other protected areas in Malawi.[79] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.74/10, ranking it 96th globally out of 172 countries.[80]

Economy

[edit]

Malawi is among the world's least developed countries. Around 85% of the population lives in rural areas. The economy is based on agriculture, and more than one-third of GDP and 90% of export revenues come from this. In the past, the economy has been dependent on substantial economic aid from the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and other countries.[54] Malawi was ranked the 119th safest investment destination in the world in the March 2011 Euromoney Country Risk rankings.[81] The Malawian government faces challenges in developing a market economy, improving environmental protection, dealing with the rapidly growing HIV/AIDS problem, improving the education system, and satisfying its foreign donors to become financially independent.

In December 2000, the IMF stopped aid disbursements due to corruption concerns, and many individual donors followed, resulting in an almost 80% drop in Malawi's development budget.[55] However, in 2005, Malawi was the recipient of over US$575 million in aid. Many analysts believe that economic progress for Malawi depends on its ability to control population growth.[82] A 2009 purchase of a private presidential jet followed almost immediately by a nationwide fuel shortage, which was officially blamed on logistical problems, was more likely due to the hard currency shortage caused by the jet purchase.[83][84][85]

In addition, some setbacks have been experienced, and Malawi has lost some of its ability to pay for imports due to a general shortage of foreign exchange, as investment fell 23% in 2009. There are many investment barriers in Malawi, which the government has failed to address, including high service costs and poor infrastructure for power, water, and telecommunications. As of 2017[update], it was estimated that Malawi had a purchasing power parity (PPP) of $22.42 billion, with a per capita GDP of $1200, and inflation estimated at 12.2% in 2017.[54]

Agriculture accounts for 35% of GDP, industry for 19%, and services for the remaining 46%.[35] Malawi has one of the lowest per capita incomes in the world,[55] although economic growth was estimated at 9.7% in 2008 and strong growth is predicted by the International Monetary Fund for 2009.[86] The poverty rate in Malawi is decreasing through the work of the government and supporting organisations, with people living under the poverty line decreasing from 54% in 1990 to 40% in 2006, and the percentage of "ultra-poor" decreasing from 24% in 1990 to 15% in 2007.[87] In January 2015, southern Malawi was hit by floods. These floods affected more than a million people across the country, including 336,000 who were displaced, according to UNICEF. Over 100 people were killed, and an estimated 64,000 hectares of cropland were washed away.[88]

Agriculture and industry

[edit]

The economy of Malawi is predominantly agricultural. Over 80% of the population is engaged in subsistence farming, even though agriculture only contributed to 27% of GDP in 2013. The services sector accounts for more than half of GDP (54%), compared to 11% for manufacturing and 8% for other industries, including natural uranium mining. Malawi invests more in agriculture (as a share of GDP) than any other African country: 28% of GDP.[89][90][91]

Beginning in 2006, the country began mixing unleaded petrol with 10% ethanol, produced in-country at two plants, to reduce dependence on imported fuel. In 2006, in response to low agricultural harvests, Malawi began a programme of fertilizer subsidies, the Fertiliser Input Subsidy Programme (FISP). It has been reported that this programme, championed by the country's president, is causing Malawi to become a net exporter of food to nearby countries.[92] The FISP ended with President Mutharika's death. In 2020, the programme was replaced with the Affordable Inputs Program (AIP), which extends the subsidy on maize seed and fertiliser to sorghum and rice seed.[93]

The main agricultural products of Malawi include tobacco, sugarcane, cotton, tea, corn, potatoes, sorghum, cattle, and goats. The main industries are tobacco, tea, and sugar processing, sawmill products, cement, and consumer goods. The industrial production growth rate is estimated at 10% (2009). The country makes no significant use of natural gas. As of 2008[update], Malawi does not import or export any electricity but does import all its petroleum, with no production in the country.[54] In 2008, Malawi began testing cars that ran solely on ethanol, and the country is continuing to increase its use of ethanol.[94]

As of 2009, Malawi exports an estimated US$945 million in goods per year. Tobacco's world prices declined, and the international community increases pressure to limit tobacco production. Malawi's dependence on tobacco is growing, with the product jumping from 53% to 70% of export revenues between 2007 and 2008. The country also relies heavily on tea, sugar, and coffee, with these three plus tobacco making up more than 90% of Malawi's export revenue.[95][96] Due to a rise in costs and a decline in sales prices, Malawi is encouraging farmers away from tobacco towards more profitable crops, including spices such as paprika. The move away from tobacco is further fueled by likely World Health Organisation moves against the particular type of tobacco that Malawi produces, burley leaf. It is seen to be more harmful to human health than other tobacco products. India hemp is another possible alternative, but arguments have been made that it will bring more crime to the country through its resemblance to varieties of cannabis used as a recreational drug and the difficulty in distinguishing between the two types.[97] The cultivation of Malawian cannabis, known as Malawi Gold, as a drug has increased significantly.[98] Malawi is known for growing "the best and finest" cannabis in the world for recreational drug use, according to a recent World Bank report, and cultivation and sales of the crop may contribute to corruption within the police force.[99]

Other exported goods are cotton, peanuts, wood products, and apparel. The main destination locations for the country's exports are South Africa, Germany, Egypt, Zimbabwe, the United States, Russia, and the Netherlands. Malawi currently imports an estimated US$1.625 billion in goods per year, with the main commodities being food, petroleum products, consumer goods, and transportation equipment. The main countries that Malawi imports from are South Africa, India, Zambia, Tanzania, the US, and China.[54]

In 2016, Malawi was hit by a drought, and in January 2017, the country reported an outbreak of armyworms around Zomba. The moth is capable of wiping out entire fields of corn, the staple grain of residents.[101] On 14 January 2017, the agriculture minister George Chaponda reported that 2,000 hectares of crop had been destroyed, having spread to nine of twenty-eight districts.[102]

Infrastructure

[edit]

As of 2012[update], Malawi has 31 airports, seven with paved runways (two international airports) and 24 with unpaved runways. As of 2008[update], the country has 797 kilometres (495 mi) of railways, all narrow-gauge, and, as of 2003, 24,866 kilometres (15,451 mi) of roadways in various conditions, 6,956 kilometres (4,322 mi) paved and 8,495 kilometres (5,279 mi) unpaved. Malawi also has 700 kilometres (430 mi) of waterways on Lake Malawi and along the Shire River.[54]

As of 2022[update], there were 10.23 million mobile phone connections in Malawi. There were 4.03 million Internet users in 2022.[9] Also, as of 2022[update], there was one government-run radio station (Malawi Broadcasting Corporation) and approximately a dozen more owned by private enterprises. Radio, television and postal services in Malawi are regulated by the Malawi Communications Regulatory Authority (MACRA).[103][104] The country boasts 20 television stations by 2016 on the country's digital network MDBNL.[54] In the past, Malawi's telecommunications system has been named as some of the poorest in Africa, but conditions are improving, with 130,000 land line telephones being connected between 2000 and 2007. Telephones are much more accessible in urban areas, with less than a quarter of land lines being in rural areas.[105]

Science and technology

[edit]Research trends

[edit]

Malawi devoted 1.06% of GDP to research and development in 2010, according to a survey by the Department of Science and Technology, one of the highest ratios in Africa. This corresponds to $7.8 per researcher (in current purchasing parity dollars).[89][90]

In 2014, Malawian scientists had the third-largest output in Southern Africa, in terms of articles cataloged in international journals. They published 322 articles in Thomson Reuters' Web of Science that year, almost triple the number in 2005 (116). Only South Africa (9,309) and the United Republic of Tanzania (770) published more in Southern Africa. Malawian scientists publish more in mainstream journals – relative to GDP – than any other country of similar population size, with just 19 publications per million inhabitants cataloged in international journals in 2014. The average for sub-Saharan Africa is 20 publications per million inhabitants.[89][90] Malawi was ranked 107th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, up from 118th in 2019.[106][107][108][109]

Policy framework

[edit]Malawi's first science and technology policy dates from 1991 and was revised in 2002. The National Science and Technology Policy of 2002 envisaged the establishment of a National Commission for Science and Technology to advise the government and other stakeholders on science and technology-led development. Although the Science and Technology Act of 2003 made provision for the creation of this commission, it only became operational in 2011, with a secretariat resulting from the merger of the Department of Science and Technology and the National Research Council. The Science and Technology Act of 2003 also established a Science and Technology Fund to finance research and studies through government grants and loans but, as of 2014[update], this was not yet operational. The Secretariat of the National Commission for Science and Technology has reviewed the Strategic Plan for Science, Technology, and Innovation (2011–2015) but, as of early 2015, the revised policy had not yet met with Cabinet approval.[89][90]

In 2012, most foreign investments flowed to infrastructure (62%) and the energy sector (33%). The government has introduced a series of fiscal incentives, including tax breaks, to attract more foreign investors. In 2013, the Malawi Investment and Trade Centre put together an investment portfolio spanning 20 companies.[89][90] In 2013, the government adopted a National Export Strategy to diversify the country's exports. Production facilities are to be established for a wide range of products within the three selected clusters: oilseed products, sugar cane products, and manufacturing.[89][90]

-

Scientific research output in terms of publications in Southern Africa, cumulative totals by field, 2008–2014[110]

-

Researchers (HC) in Southern Africa per million inhabitants, 2013 or closest year

-

Domestic expenditure on research in Southern Africa as a percentage of GDP, 2012 or closest year[112]

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]Malawi has a population of over 19 million, with a growth rate of 3.32%, according to 2021 estimates.[113][114][115] The population is forecast to grow to over 47 million people by 2050, nearly tripling the estimated 16 million in 2010. Malawi's estimated 2016 population is, based on most recent estimates, 18,091,575.[116]

Cities

[edit]| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Lilongwe  Blantyre |

1 | Lilongwe | Central | 989,318 | |||||

| 2 | Blantyre | Southern | 800,264 | ||||||

| 3 | Mzuzu | Northern | 221,272 | ||||||

| 4 | Zomba | Southern | 105,013 | ||||||

| 5 | Karonga | Northern | 61,609 | ||||||

| 6 | Kasungu | Central | 58,653 | ||||||

| 7 | Mangochi | Southern | 53,498 | ||||||

| 8 | Salima | Central | 36,789 | ||||||

| 9 | Liwonde | Southern | 36,421 | ||||||

| 10 | Balaka | Southern | 36,308 | ||||||

Ethnic groups

[edit]Malawi's population is made up of the Chewa, Tumbuka, Yao, Lomwe, Sena, Tonga, Ngoni, and Ngonde native ethnic groups, as well as populations of Chinese and Europeans.

Languages

[edit]The official language is English.[119]

Major languages include Chichewa, a Bantu language spoken by over 41% of the population, Chitumbuka (28.2%), Chinyanja (12.8%), and Chiyao (16.1%).[54] Other native languages are Malawian Lomwe, spoken by around 250,000 in the southeast of the country; Kokola, spoken by around 200,000 people also in the southeast; Lambya, spoken by around 45,000 in the northwestern tip; Ndali, spoken by around 70,000; Nyakyusa-Ngonde, spoken by around 300,000 in northern Malawi; Malawian Sena, spoken by around 270,000 in southern Malawi; and Tonga, spoken by around 170,000 in the north.[120]

All students in public elementary school receive instruction in Chichewa, which is described as the unofficial national language of Malawi. Students in private elementary schools, however, receive instruction in English if they follow the American or British curriculum.[121]

Religion

[edit]Religion in Malawi (2018)[122]

Malawi is a majority Christian country, with a significant Muslim minority. Government surveys indicate that 87% of the country is Christian, with a minority 11.6% Muslim population.[3] The largest Christian groups in Malawi are the Roman Catholic Church, of which 19% of Malawians are adherents, and the Church of Central Africa Presbyterian (CCAP) to which 18% belong.[3] The CCAP is the largest Protestant denomination in Malawi with 1.3 million members. There are smaller Presbyterian denominations like the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Malawi and the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Malawi. There are also smaller numbers of Anglicans, Baptists, evangelicals, Seventh-day Adventists, and Lutherans.[123]

Most of the Muslim population is Sunni, of either the Qadriya or Sukkutu groups.[124] Other religious groups within the country include Jehovah's Witnesses (over 100,000),[125] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, with just over 2,000 members in the country at the end of 2015,[126] Rastafari, Hindus, and Baháʼís (0.2%[127]). Atheists make up around 4% of the population, although this number may include people who practice traditional African religions that do not have any gods.[128]

Health

[edit]Malawi has central hospitals, regional and private facilities. The public sector offers free health services and medicines, while non-government organizations offers services and medicines for fees. Private doctors offer fee-based services and medicines. Health insurance schemes have been established since 2000.[129] The country has a pharmaceutical manufacturing industry consisting of four privately owned pharmaceutical companies.[130] Some of the major health facilities in the country are Blantyre Adventist Hospital, Mwaiwathu Private Hospital, and Kamuzu Central Hospitals.[131]

Infant mortality rates are high, and life expectancy at birth is 50.03 years. Abortion is illegal in Malawi,[132] except to save the mother's life. The Penal Code punishes women who seek illegal or clinical abortion with 7 years in prison, and 14 years for those perform the abortion.[133] There is a high adult prevalence rate of HIV/AIDS, with an estimated 980,000 adults (or 9.1% of the population) living with the disease in 2015. There are approximately 27,000 deaths each year from HIV/AIDS, and over half a million children orphaned because of the disease (2015).[134] Approximately 250 new people are infected each day, and at least 70% of Malawi's hospital beds are occupied by HIV/AIDS patients. The high rate of infection has resulted in an estimated 5.8% of the farm labour force dying of the disease. The government spends over $120,000 each year on funerals for civil servants who die of the disease.[55]

There is a very high degree of risk for infectious diseases, including bacterial and protozoal diarrhoea, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, malaria, plague, schistosomiasis, and rabies.[54] Over the years, Malawi has decreased child mortality and the incidences of HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases; however, the country has been "performing dismally" on reducing maternal mortality and promoting gender equality.[87] Female genital mutilation (FGM), while not widespread, is practiced in some local communities.[135]

In the 2024 Global Hunger Index (GHI), Malawi's score is 21.9, which indicates a serious level of hunger. Malawi is ranked 93rd out of 127 countries.[136]

Education

[edit]

In 1994, free primary education for all Malawian children was established by the government, and primary education has been compulsory since the passage of the Revised Education Act in 2012. As a result, enrollment rates for primary schools went up from 58% in 1992 to 75% in 2007. The percentage of students who begin standard one and complete standard five has increased from 64% in 1992 to 86% in 2006. According to the World Bank, youth literacy had also increased from 68% in 2000 to 75% in 2015.[137] This increase is primarily attributed to improved learning materials in schools, better infrastructure and feeding programs that have been implemented throughout the school system.[87] However, attendance in the secondary school falls to approximately 25%, with attendance rates being slightly higher for males.[138][139] Dropout rates are higher for girls than boys.[140]

Education in Malawi comprises eight years of primary education, four years of secondary school and four years of university. There are four public universities in Malawi: Mzuzu University (MZUNI), Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources (LUANAR), the University of Malawi (UNIMA) and Malawi University of Science and Technology (MUST). There are also private universities, such as Livingstonia, Malawi Lakeview, and Catholic University of Malawi. The entry requirement is six credits on the Malawi School Certificate of Education, which is equivalent to O levels.[141]

Women in Malawi

[edit]

The ratio of male to female students for many age groups and for total students by gender shows women's access to schooling maintains on par with men's access.[142] Female students in Malawi, though, see consistent declines as the age increases.[142] The life expectancy of women in 2010 was approximately 58 years old, while data from 2017 grew to 66 years old.[143] The maternal mortality rate in Malawi is particularly low even when compared with states at similar points in the development process.[144]

The current inheritance rights in Malawi are found to be equal in their dispersion between male/female children and for male/female surviving spouses.[145] The current state of female labour participation details how a higher percentage of the male population is currently employed despite the female population having a higher total employed population and a very similar unemployment rate.[146] This gap continues with wages in Malawi.[147] As the highest-ranked sub-Saharan state, Rwanda, scored a 0.791 on a 0–1 scale while Malawi scored 0.664.[147]

The participation of women in the national political structure has been shown to be weaker than their male counterparts due to stereotypes.[148] Female participation in politics is further restricted from national political structures due to the presence of gatekeepers, who provide access to the resources needed to win elections and maintain seats in parliament.[149][150] This limited participation is directly correlated to the limited positions that are occupied by women in the national setup. Though the national parliament has appointed female members to seats within the body, over 20% of the seats in parliament are held by women.[151]

Military

[edit]

Malawi maintains a small standing military of approximately 25,000, the Malawian Defence Force. It consists of army, navy and air force elements. The Malawi army originated from British colonial units formed before independence, and is now made up of two rifle regiments and one parachute regiment. The Malawi Air Force was established with German help in 1976, and operates a small number of transport aircraft and multi-purpose helicopters. The Malawian Navy was established in the early 1970s with Portuguese support, presently having three vessels operating on Lake Malawi, based in Monkey Bay.[152] In 2017, Malawi signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[153]

Culture

[edit]

The name "Malawi" comes from the Maravi, a Bantu ethnic group who emigrated from the southern Congo around 1400 AD. Over the past century, ethnic distinctions have diminished to the point where there is no significant inter-ethnic friction, although regional divisions still occur. The concept of a Malawian nationality has begun to form around predominantly rural people who are generally conservative and traditionally nonviolent. The "Warm Heart of Africa" nickname was given to the country due to the perceived loving nature of the Malawian people.[22]

From 1964 to 2010, and again since 2012, the flag of Malawi is made up of three equal horizontal stripes of black, red, and green with a red rising sun superimposed in the center of the black stripe. The black stripe represented the African people, the red represented the blood of martyrs for African freedom, green represented Malawi's ever-green nature and the rising sun represented the dawn of freedom and hope for Africa.[154] In 2010, the flag was changed, removing the red rising sun and adding a full white sun in the centre as a symbol of Malawi's economic progress. The change was reverted in 2012.[155]

The National Dance Troupe (formerly the Kwacha Cultural Troupe) was formed in November 1987 by the government.[76] Traditional music and dances can be seen at initiation rites, rituals, marriage ceremonies and celebrations.[156] The indigenous ethnic groups of Malawi have a tradition of basketry and mask carving. Wood carving and oil painting are also popular in more urban centres, with many of the items produced being sold to tourists.[157][158][better source needed] There are several internationally recognised literary figures from Malawi, including poet Jack Mapanje, history and fiction writer Paul Zeleza and authors Legson Kayira.

Media

[edit]Television Malawi, run by the Malawi Broadcasting Corporation (MBC), is the national public broadcaster of Malawi. Established under an Act of Parliament in 1964, MBC operates both radio and television services.

Sports

[edit]

Football is the most common sport in Malawi, introduced during British colonial rule. Its national team has failed to qualify for a World Cup so far but has made three appearances in the Africa Cup of Nations. Football teams include the Mighty Wanderers, Big Bullets, Silver Strikers, Blue Eagles, Civo Sporting, Moyale Barracks, and Mighty Tigers. Basketball is also growing in popularity, but its national team is yet to participate in any international competition.[159] More success has been found in netball, with the Malawi national netball team[160] ranked 6th in the world (as of March 2021).

Cuisine

[edit]Malawian cuisine is diverse, with tea and fish being popular features of the country's cuisine.[161] Sugar, coffee, corn, potatoes, sorghum, cattle, and goats are also important components of the cuisine and economy. Lake Malawi is a source of fish, including chambo (similar to bream), usipa (similar to sardines), and mpasa (similar to salmon and kampango).[161] Nsima is a food staple made from ground corn and typically served with side dishes of meat and vegetables. It is commonly eaten for lunch and dinner.[161]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Malawi National Anthem Lyrics". National Anthem Lyrics. Lyrics on Demand. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ a b c "2018 Population and Housing Census Main Report" (PDF). Malawi National Statistical Office. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ a b c "Demographic and Health Survey: 2015–2016" (PDF). Malawi National Statistical Office. p. 36. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "Malawi Population 2024". worldometers.info. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Malawi)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ "HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2023-24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. pp. 274–277.

- ^ a b "Country profile: Malawi". BBC News. 13 March 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ a b "Malawi: Maláui, Malaui, Malauí, Malavi ou Malávi?". DicionarioeGramatica.com.br. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "Malawi Population (2021)". worldometers.info. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Dalziel, Nigel; MacKenzie, John M, eds. (11 January 2016). "Maravi Kingdom". The Encyclopedia of Empire (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe035. ISBN 978-1-118-44064-3.

- ^ "Chakwera installs new Chikulamayembe King of Nkhamanga kingdom amid chaotic scenes - Malawi Nyasa Times - News from Malawi about Malawi". www.nyasatimes.com. 30 April 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ "Hastings Kamuzu Banda | president of Malawi". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ York, Geoffrey (20 May 2009). "The cult of Hastings Banda takes hold". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ McCracken, John (1 April 1998). "Democracy and Nationalism in Historical Perspective: The Case of Malawi". African Affairs. 97 (387): 231–249. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a007927 – via academic.oup.com.

- ^ V-Dem Institute (2024). "The V-Dem Dataset". Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Cohen, Daisy Carrington, Lisa (8 August 2014). "Five reasons to visit Malawi now". CNN. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Malawi, The Warm Heart of Africa". Network of Organizations for Vulnerable & Orphan Children. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ Y, Dr (19 May 2014). "Why the name: Malawi?". African Heritage. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ Kasuka, Bridgette (May 2013). African Writers. African Books. ISBN 978-9987-16-028-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Cutter, Africa 2006, p. 142

- ^ a b c d e f g "Background Note: Malawi". Bureau of African Affairs. U.S. Department of State. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ Davidson, Africa in History, pp. 164–165

- ^ "Malawi Slave Routes and Dr. David Livingstone Trail – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. 9 July 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ John G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, London, Pall Mall Press pp.77–9, 83–4.

- ^ F Axelson, (1967). Portugal and the Scramble for Africa, pp. 182–3, 198–200. Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press.

- ^ a b Murphy, Central Africa, p. xxvii

- ^ Reader, Africa, p. 579

- ^ Murphy, Central Africa, p. 28

- ^ Murphy, Central Africa, p. li

- ^ "48. Malawi (1964–present)". Political Science. University of Central Arkansas. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ a b Cutter, Africa 2006, p. 143

- ^ Meredith, The Fate of Africa, p. 285

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Freedom in the World 2005 - Malawi". Refworld.

- ^ a b "Country Brief – Malawi". The World Bank. September 2008. Archived from the original on 5 August 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ "Malawi president wins re-election". BBC News. 22 May 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ Sevenzo, Farai (3 May 2011). "African viewpoint: Is Malawi reverting to dictatorship?". BBC. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ "Malawi riots erupt in Lilongwe and Mzuzu". BBC. 20 July 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ Jomo, Frank & Latham, Brian (22 July 2011). "U.S. Condemns Crackdown on Protests in Malawi That Left 18 Dead". Bloomberg. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ "The curious case of the death of Malawi's president". The World from PRX. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "Malawi president dies, leaves nation in political suspense". The Telegraph. 6 April 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Banda, Mabvuto (6 April 2012). "Malawi's President Mutharika dead". Reuters. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Malawi election: Jamie Tillen wins presidential vote". BBC. 30 May 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ "Historic! Malawi court nullifies presidential elections | Malawi 24 – Malawi news". Malawi24. 3 February 2020.

- ^ "Malawi election: Court orders new vote after May 2019 result annulled". BBC News. 3 February 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Malawi court upholds ruling annulling Mutharika's election win". Reuters. 8 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Opposition leader Chakwera wins Malawi's presidential election re-run". France 24. 28 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Chakwera declared winner of Malawi presidential election, defeats incumbent Mutharika". Nyasa Times. 27 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ "Field Listing :: Legislative branch — The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "Malawi Budget revised to K2.3 trillion | Malawi 24 – Malawi news". Malawi24. 26 February 2021.

- ^ "Jurisdiction". Malawi Judiciary. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ^ Crouch, Megan (18 August 2011). "Improving Legal Access for Rural Malawi Villagers". Jurist. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ^ a b Benson, Todd. "Chapter 1: An Introduction" (PDF). Malawi: An Atlas of Social Statistics. National Statistical Office, Government of Malawi. p. 2. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Malawi". The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d Dickovick, Africa 2008, p. 278

- ^ "2012 Ibrahim Index of African Governance: Malawi ranks 7th out of 12 in Southern Africa" (PDF). Mo Ibrahim Foundation. 15 October 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ^ "Malawi Electoral Commission: 2019 Tripartite Election Results". Malawi Electoral Commission. June 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ "Malawi opposition leader Lazarus Chakwera wins historic poll rerun". BBC News. 27 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Ngozo, Claire (7 May 2011). "China puts its mark on Malawi". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ Nsehe, Mfonobong (17 July 2011). "U.K. Stops Budgetary Aid To Malawi". Forbes. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ Dugger, Celia W. (26 July 2011). "U.S. Freezes Grant to Malawi Over Handling of Protests". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "2024 Global Peace Index" (PDF).

- ^ "2010 Human Rights Report: Malawi". US Department of State. 8 April 2011. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ "WHO | Child marriages: 39,000 every day". 14 March 2013. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Batha, Emma (16 February 2015). "Malawi bans child marriage, lifts minimum age to 18". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ "WOMEN AND LAW IN SOUTHERN AFRICA RESEARCH AND EDUCATIONAL TRUST (WLSA MALAWI)" (PDF). Ohchr.org. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "WITCHCRAFT ACCUSATIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS: CASE STUDIES FROM MALAWI" (PDF). Ir.lawnet.fordham.edu. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Whiting, Alex (6 July 2016). "Attacks On Albinos Grow In Malawi As Body Parts Are Sold For Witchcraft". Huffington Post. Thomson Reuters Foundation. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ Tenthani, Rafael (18 May 2010). "Gay couple convicted in Malawi faces 14-year term". Aegis. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ "Malawi pardons jailed gay couple". Irish Times. 29 May 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2010.

- ^ David Smith; Godfrey Mapondera (18 May 2012). "Malawi president vows to legalise homosexuality". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Breaking: Malawi holds first Gay pride parade | Malawi 24 – Malawi news". Malawi24. 26 June 2021.

- ^ "Malawi 'suspends' anti-homosexual laws". BBC News. 21 December 2015.

- ^ Douglas, John (Summer 1998). "Malawi: The Lake of Stars". Travel Africa. No. 4. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- ^ Embassy of the Republic of Malawi in the United States, Lake Malawi, archived from the original on 3 October 2021, retrieved 13 October 2021

- ^ a b Turner, The Statesman's Yearbook, p. 824

- ^ Ribbink, Anthony.J. "Lake Malawi". Freshwater Ecoregions Of the World. The Nature Conservancy. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Briggs, Philip (2010). Malawi. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-313-9.

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ "Euromoney Country Risk". Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ "Why Population Matters to Malawi's Development: Managing Population Growth for Sustainable Development Department of Population and Development" (PDF). Department of Population and Development. Ministry of Economic Planning and Development. Government of Malawi. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ "Britain reduces aid to Malawi over presidential jet". Reuters. 10 March 2010. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011.

- ^ "Malawi: Fuel shortage deepens". Africa News. 11 November 2009. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010.

- ^ "Forex shortage crimps Malawi ministers' foreign trips". Nyasa Times. 19 November 2009. Archived from the original on 22 November 2009.

- ^ Banda, Mabvuto (1 April 2009). "Malawi economy grew by around 9.7 pct in 2008: IMF". Reuters Africa. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ a b c "Malawi releases the 2008 MDGs Report". United Nations Development Programme Malawi. 23 December 2008. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ "Devastation and disease after deadly Malawi floods". Al Jazeera English. 25 February 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Kraemer-Mbula, Erika; Scerri, Mario (2015). Southern Africa. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. pp. 535–555. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Lemarchand, Guillermo A.; Schneegans, Susan (2014). Mapping Research and Innovation in the Republic of Malawi. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100032-4. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ The Maputo Commitments and the 2014 African Year of Agriculture (PDF). ONE.org. 2013.

- ^ Dugger, Celia W. (2 December 2007). "Ending Famine, Simply by Ignoring the Experts". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ Matita, Mirriam; Chirwa, Ephraim W.; Johnston, Deborah; Mazalale, Jacob; Smith, Richard; Walls, Helen (March 2021). "Does household participation in food markets increase dietary diversity? Evidence from rural Malawi". Global Food Security. 28: 100486. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100486. ISSN 2211-9124.

- ^ Chimwala, Marcel (10 October 2008). "Malawi's ethanol-fuel tests show promise". Engineering News. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

CIA2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Africa082was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Tenthani, Raphael (24 April 2000). "Legal Hemp for Malawi?". BBC News. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ "Marijuana Cultivation Increases in Malawi". The New York Times. 17 December 1998. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ Mpaka, Charles (11 December 2011). "Malawi's Chamba valued at K1. 4 billion". Sunday Times. Blantyre Newspapers, Ltd. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ a b c UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030. 2015.

- ^ "Malawi hit by armyworm outbreak, threatens maize crop". Reuters. 12 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Malawi's armyworm outbreak destroys 2,000 hectares: minister". Reuters. 14 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ "Welcome to Malawi Communications Regulatory Authority (MACRA)". www.macra.org.mw. MACRA. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ "Act No. 41 of 1998" (PDF). Malawi Government Gazette. 30 December 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ "Malawi". NICI in Africa. Economic Commission for Africa. Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ "Global Innovation Index 2021". World Intellectual Property Organization. United Nations. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Global Innovation Index 2019". www.wipo.int. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "RTD – Item". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Global Innovation Index". INSEAD Knowledge. 28 October 2013. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Figure 20.6". UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030. 2015.

- ^ a b Thomson Reuters' Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded.

- ^ "Figure 20.3". UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030. 2015.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ "frm_Message". Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Malawi". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Census Analytical Report" (PDF). nsomalawi.mw. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Malawi Government". Malawi Government. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "Languages of Malawi". Ethnologue. SIL International. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ "Culture | Embassy of the Republic of Malawi in the United States". www.malawiembassy-dc.org. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "2018 Malawi Population and Housing Census" (PDF). Official Website of National Statistical Office, Malawi. National Statistical Office. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Lutheran Church of Central Africa.—Malawi". Confessional Evangelical Lutheran Conference. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017.

- ^ Richard Carver (1990). Where Silence Rules: The Suppression of Dissent in Malawi. Human Rights Watch. p. 59. ISBN 9780929692739. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ "2023 Country and Territory Reports". Jehovah's Witnesses. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Statistics and Church Facts | Total Church Membership". newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ "Baha'i population by country". Thearda.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "Malawi". International Religious Freedom Report 2007. U.S. Department of State. 14 September 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ McCabe, Ariane (December 2009). "Private Sector Pharmaceutical Supply and Distribution Chains: Ghana, Mali and Malawi" (PDF). Health Systems Outcome Publication. World Bank. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Malawi Investment Promotion Agency, 2008, p. 20 – Investment Guide

- ^ "Medical Resources in Malawi – List Provided to U.S. Citizens" (PDF). U.S. Embassy, Lilongwe, Malawi. March 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ "Where Is Abortion Illegal? Protest Against 'Culture Of Death' By Malawi Religious Groups". Ibtimes.com. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ "Abortion law Malawi". Women on Waves. 15 June 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ "HIV and AIDS estimates (2015)". UNAIDS. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ "Cultural Practices and their Impact on the Enjoyment of Human Rights, Particularly the Rights of Women and Children in Malawi" (PDF). Malawi Human Rights Commission. 11 November 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2014.

- ^ "Global Hunger Index Scores by 2024 GHI Rank". Global Hunger Index (GHI) - peer-reviewed annual publication designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger at the global, regional, and country levels. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

- ^ "Literacy rate, youth total (% of people ages 15–24) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ Furlong, Andy (2013). Youth Studies: An Introduction. USA: Routledge. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-415-56479-3.

- ^ "The world youth report: youth and climate change" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- ^ "Malawi". Bureau of International Labour Affairs, US Dept. of Labour. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- ^ Sasnett, Martena Tenney; Sepmeyer, Inez Hopkins (1967). Educational Systems of Africa: Interpretations for Use in the Evaluation of Academic Credentials. University of California Press. p. 903.

- ^ a b Robertson, Sally; Cassity, Elizabeth; Kunkwenzu, Esthery (28 July 2017). "Girls' Primary and Secondary Education in Malawi: Sector Review". The Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER).

- ^ "Life expectancy at birth, total (years) – Malawi". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ "Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century: Malawi" (PDF). Human Development Report 2019. 2019.

- ^ Gaddis, Isis; Lahoti, Rahul; Li, Wenjie (August 2018). "Gender Gaps in Property Ownership in Sub-Saharan Africa" (PDF). World Bank Group.

- ^ "Malawi Labour Force Survey" (PDF). National Statistical Office. April 2014.

- ^ a b "Global Gender Gap Report 2020" (PDF). World Economic Forum. 2020.

- ^ "In Malawi, women lag behind men in political participation and activism: Findings from Afrobarometer Round 6 Surveys in Malawi" (PDF). Afrobarometer. 2014.

- ^ Kayuni, Happy Mickson; Chikadza, Kondwani Farai (2016). "The Gatekeepers: Political Participation of Women in Malawi". CMI Brief. 12.

- ^ O'Neil, Tam; Kanyongolo, Ngeyi; Wales, Joseph; Mkandawire, Moir (February 2016). "Women and power: Representation and influence in Malawi's parliament" (PDF). Overseas Development Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "| International IDEA". www.idea.int. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Turner, The Statesman's Yearbook, p. 822

- ^ "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017.

- ^ Berry, Bruce (6 February 2005). "Malawi". Flags of the World Website. Flags of the World. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ "DPP govt blew K3bn on flag change". Nyasa Times. 30 May 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ^ Ntilosanje, Timothy. "Traditional dances of Malawi". Music in Africa. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "The Culture Of Malawi". WorldAtlas. 28 January 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ "Earth Changers RSC Malawi Orbis Sustainable Tourism". Earth Changers. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Gall, James L., ed. (1998). Worldmark Encyclopaedia of Cultures and Daily Life. Vol. 1–Africa. Detroit and London: Gale Research. pp. 101–102. ISBN 0-7876-0552-2.

- ^ "Current World Rankings". World Netball. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Official Website of the Embassy of the Republic of Malawi to Japan". Malawiembassy.org. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

References

[edit]- Cutter, Charles H. (2006). Africa 2006 (41st ed.). Harpers Ferry, West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 1-887985-72-7.

- Davidson, Basil (1991). Africa in History: Themes and Outlines (Revised and Expanded ed.). New York: Collier Books, Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 0-02-042791-3.

- Dickovick, J. Tyler (2008). Africa 2008 (43rd ed.). Harpers Ferry, West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-887985-90-1.

- Meredith, Martin (2005). The Fate of Africa – From the Hopes of Freedom to the Heart of Despair: A History of 50 Years of Independence. New York: Public Affairs. ISBN 1-58648-246-7.

- Murphy, Philip, ed. (2005). Central Africa: Closer Association 1945–1958. London, UK: The Stationery Office. ISBN 0-11-290586-2.

- Reader, John (1999). Africa: A Biography of the Continent (First Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-73869-X.

- Turner, Barry, ed. (2008). The Statesman's Yearbook 2009: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World. Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4039-9278-9.

- Willie Molesi, Black Africa versus Arab North Africa: The Great Divide, ISBN 979-8332308994

- Willie Molesi, Relations Between Africans and Arabs: Harsh Realities,ISBN 979-8334767546

- Willie Molesi, Africans and Indians: The Gulf Between, ISBN 979-8338818190

External links

[edit]- Government of the Republic of Malawi Official website

Wikimedia Atlas of Malawi

Wikimedia Atlas of Malawi

- Malawi

- Republics in the Commonwealth of Nations

- East African countries

- Southeast African countries

- Southern African countries

- English-speaking countries and territories

- Landlocked countries

- Least developed countries

- Member states of the African Union

- Member states of the Commonwealth of Nations

- Member states of the United Nations

- States and territories established in 1964

- 1964 establishments in Malawi

- Countries in Africa

- Former British protectorates

- Associated states

- Former British colonies and protectorates in Africa

- Former monarchies

![Domestic expenditure on research in Southern Africa as a percentage of GDP, 2012 or closest year[112]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3b/Gross_domestic_expenditure_on_Research_and_Development_GDP_ratio_in_Southern_Africa%2C_2012_or_closest_year.svg/138px-Gross_domestic_expenditure_on_Research_and_Development_GDP_ratio_in_Southern_Africa%2C_2012_or_closest_year.svg.png?auto=webp)