Violin

A standard modern violin shown from the top and the side | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | fiddle |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.322-71 (Composite chordophone sounded by a bow) |

| Developed | Early 16th century |

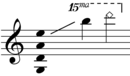

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| |

| Musicians | |

| Builders | |

| Sound sample | |

|

Recording of violinist demonstrating different sounds of the violin | |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Violin |

|---|

| Violinists |

| Fiddle |

| Fiddlers |

| History |

| Musical styles |

| Technique |

| Acoustics |

| Construction |

| Luthiers |

| Family |

The violin, sometimes referred as a fiddle,[a] is a wooden chordophone, and is the smallest, and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in regular use in the violin family. Smaller violin-type instruments exist, including the violino piccolo and the pochette, but these are virtually unused. Most violins have a hollow wooden body, and commonly have four strings (sometimes five), usually tuned in perfect fifths with notes G3, D4, A4, E5, and are most commonly played by drawing a bow across the strings. The violin can also be played by plucking the strings with the fingers (pizzicato) and, in specialized cases, by striking the strings with the wooden side of the bow (col legno).

Violins are important instruments in a wide variety of musical genres. They are most prominent in the Western classical tradition, both in ensembles (from chamber music to orchestras) and as solo instruments. Violins are also important in many varieties of folk music, including country music, bluegrass music, and in jazz. Electric violins with solid bodies and piezoelectric pickups are used in some forms of rock music and jazz fusion, with the pickups plugged into instrument amplifiers and speakers to produce sound. The violin has come to be incorporated in many non-Western music cultures, including Indian music and Iranian music. The name fiddle is often used regardless of the type of music played on it.

The violin was first known in 16th-century Italy, with some further modifications occurring in the 18th and 19th centuries to give the instrument a more powerful sound and projection. In Europe, it served as the basis for the development of other stringed instruments used in Western classical music, such as the viola.[1][2][3]

Violinists and collectors particularly prize the fine historical instruments made by the Stradivari, Guarneri, Guadagnini and Amati families from the 16th to the 18th century in Brescia and Cremona (Italy) and by Jacob Stainer in Austria. According to their reputation, the quality of their sound has defied attempts to explain or equal it, though this belief is disputed.[4][5] Great numbers of instruments have come from the hands of less famous makers, as well as still greater numbers of mass-produced commercial "trade violins" coming from cottage industries in places such as Saxony, Bohemia, and Mirecourt. Many of these trade instruments were formerly sold by Sears, Roebuck and Co. and other mass merchandisers.

The components of a violin are usually made from different types of wood. Violins can be strung with gut, Perlon or other synthetic, or steel strings. A person who makes or repairs violins is called a luthier or violinmaker. One who makes or repairs bows is called an archetier or bowmaker.

Etymology

The word "violin" was first used in English in the 1570s.[6] The word "violin" comes from "Italian violino, [a] diminutive of viola. The term "viola" comes from the expression for "tenor violin" in 1797, from Italian and Old Provençal viola, [which came from] Medieval Latin vitula as a term which means 'stringed instrument', perhaps [coming] from Vitula, Roman goddess of joy..., or from related Latin verb vitulari, "to cry out in joy or exaltation."[7] The related term Viola da gamba meaning 'bass viol' (1724) is from Italian, literally "a viola for the leg" (i.e. to hold between the legs)."[7] A violin is the "modern form of the smaller, medieval viola da braccio." ("arm viola")[6]

The violin is often called a fiddle. "Fiddle" can be used as the instrument's customary name in folk music, or as an informal name for the instrument in other styles of music.[8] The word "fiddle" was first used in English in the late 14th century.[8] The word "fiddle" comes from "fedele, fydyll, fidel, earlier fithele, from Old English fiðele 'fiddle', which is related to Old Norse fiðla, Middle Dutch vedele, Dutch vedel, Old High German fidula, German Fiedel, 'a fiddle'; all of uncertain origin." As to the origin of the word "fiddle", the "...usual suggestion, based on resemblance in sound and sense, is that it is from Medieval Latin vitula."[8]

History

The earliest stringed instruments were mostly plucked (for example, the Greek lyre). Two-stringed, bowed instruments, played upright and strung and bowed with horsehair, may have originated in the nomadic equestrian cultures of Central Asia, in forms closely resembling the modern-day Mongolian Morin huur and the Kazakh Kobyz. Similar and variant types were probably disseminated along east–west trading routes from Asia into the Middle East,[9][10] and the Byzantine Empire.[11][12]

Rebec, fiddle and lira da braccio are generally considered the ancestors of the violin,[13] Several sources suggest alternative possibilities for the violin's origins, such as northern or western Europe.[14][15][16] The first makers of violins probably borrowed from various developments of the Byzantine lyra. These included the vielle (also known as the fidel or viuola) and the lira da braccio.[11][17] The violin in its present form emerged in early 16th-century northern Italy. The earliest pictures of violins, albeit with three strings, are seen in northern Italy around 1530, at around the same time as the words "violino" and "vyollon" are seen in Italian and French documents. One of the earliest explicit descriptions of the instrument, including its tuning, is from the Epitome musical by Jambe de Fer, published in Lyon in 1556.[18] By this time, the violin had already begun to spread throughout Europe.

The violin proved very popular, both among street musicians and the nobility; the French king Charles IX ordered Andrea Amati to construct 24 violins for him in 1560.[19] One of these "noble" instruments, the Charles IX, is the oldest surviving violin. The finest Renaissance carved and decorated violin in the world is the Gasparo da Salò (c.1574) owned by Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria and later, from 1841, by the Norwegian virtuoso Ole Bull, who used it for forty years and thousands of concerts, for its very powerful and beautiful tone, similar to that of a Guarneri.[20] "The Messiah" or "Le Messie" (also known as the "Salabue") made by Antonio Stradivari in 1716 remains pristine. It is now located in the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford.[21]

The most famous violin makers (luthiers) between the 16th century and the 18th century include:

- The school of Brescia, beginning in the late 14th century with liras, violettas, violas and active in the field of the violin in the first half of the 16th century

- The Dalla Corna family, active 1510–1560 in Brescia and Venice

- The Micheli family, active 1530–1615 in Brescia

- The Inverardi family active 1550–1580 in Brescia

- The Gasparo da Salò family, active 1530–1615 in Brescia and Salò

- Giovanni Paolo Maggini, student of Gasparo da Salò, active 1600–1630 in Brescia

- The Rogeri family, active 1661–1721 in Brescia

- The school of Cremona, beginning in the second half of the 16th century with violas and violone and in the field of violin in the second half of the 16th century

- The Amati family, active 1550–1740 in Cremona

- The Guarneri family, active 1626–1744 in Cremona and Venice

- The Stradivari family, active 1644–1737 in Cremona[22]

- The Rugeri family, active 1650–1740 in Cremona

- Carlo Bergonzi (luthier) (1683-1747) in Cremona

- The school of Venice, with the presence of several makers of bowed instruments from the early 16th century out of more than 140 makers of string instruments registered between 1490 and 1630.[23]

- The Linarolo family, active 1505–1640 in Venice

- Matteo Goffriller, known for his celli, active 1685–1742 in Venice

- Pietro Guarneri, son of Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri and from Cremona, active 1717–1762 in Venice

- Domenico Montagnana, active circa 1700–1750 in Venice

- Santo Serafin, active before 1741 until 1776 in Venice

Significant changes occurred in the construction of the violin in the 18th century, particularly a longer neck which is angled more toward the back of the instrument than in earlier examples, heavier strings, and a heavier bass bar. The majority of old instruments have undergone these modifications, and hence are in a significantly different state than when they left the hands of their makers, doubtless with differences in sound and response.[24] But it is in their present (modified) condition that these instruments have set the standard for perfection in violin craftsmanship and sound, and violin makers all over the world try to come as close to this ideal as possible.

To this day, instruments from the so-called Golden Age of violin making, especially those made by Stradivari, Guarneri del Gesù, and Montagnana, are the most sought-after instruments by both collectors and performers. The current record amount paid for a Stradivari violin is £9.8 million (US$15.9 million at that time), when the instrument known as the Lady Blunt was sold by Tarisio Auctions in an online auction on June 20, 2011.[25]

Construction and mechanics

A violin generally consists of a spruce top (the soundboard, also known as the top plate, table, or belly), maple ribs and back, two endblocks, a neck, a bridge, a soundpost, four strings, and various fittings, optionally including a chinrest, which may attach directly over, or to the left of, the tailpiece. A distinctive feature of a violin body is its hourglass-like shape and the arching of its top and back. The hourglass shape comprises two upper bouts, two lower bouts, and two concave C-bouts at the waist, providing clearance for the bow. The "voice" or sound of a violin depends on its shape, the wood it is made from, the graduation (the thickness profile) of both the top and back, the varnish that coats its outside surface and the skill of the luthier in doing all of these steps. The varnish and especially the wood continue to improve with age, making the fixed supply of old well-made violins built by famous luthiers much sought-after.

The majority of glued joints in the instrument use animal hide glue rather than common white glue for a number of reasons. Hide glue is capable of making a thinner joint than most other glues. It is reversible (brittle enough to crack with carefully applied force and removable with hot water) when disassembly is needed. Since fresh hide glue sticks to old hide glue, more original wood can be preserved when repairing a joint. (More modern glues must be cleaned off entirely for the new joint to be sound, which generally involves scraping off some wood along with the old glue.) Weaker, diluted glue is usually used to fasten the top to the ribs, and the nut to the fingerboard, since common repairs involve removing these parts. The purfling running around the edge of the spruce top provides some protection against cracks originating at the edge. It also allows the top to flex more independently of the rib structure. Painted-on faux purfling on the top is usually a sign of an inferior instrument. The back and ribs are typically made of maple, most often with a matching striped figure, referred to as flame, fiddleback, or tiger stripe.

The neck is usually maple with a flamed figure compatible with that of the ribs and back. It carries the fingerboard, typically made of ebony, but often some other wood stained or painted black on cheaper instruments. Ebony is the preferred material because of its hardness, beauty, and superior resistance to wear. Fingerboards are dressed to a particular transverse curve, and have a small lengthwise "scoop," or concavity, slightly more pronounced on the lower strings, especially when meant for gut or synthetic strings. Some old violins (and some made to appear old) have a grafted scroll, evidenced by a glue joint between the pegbox and neck. Many authentic old instruments have had their necks reset to a slightly increased angle, and lengthened by about a centimeter. The neck graft allows the original scroll to be kept with a Baroque violin when bringing its neck into conformance with modern standards.

The bridge is a precisely cut piece of maple that forms the lower anchor point of the vibrating length of the strings and transmits the vibration of the strings to the body of the instrument. Its top curve holds the strings at the proper height from the fingerboard in an arc, allowing each to be sounded separately by the bow. The sound post, or soul post, fits precisely inside the instrument between the back and top, at a carefully chosen spot near the treble foot of the bridge, which it helps support. It also influences the modes of vibration of the top and the back of the instrument.

The tailpiece anchors the strings to the lower bout of the violin by means of the tailgut, which loops around an ebony button called the tailpin (sometimes confusingly called the endpin, like the cello's spike), which fits into a tapered hole in the bottom block. The E string will often have a fine tuning lever worked by a small screw turned by the fingers. Fine tuners may also be applied to the other strings, especially on a student instrument, and are sometimes built into the tailpiece. The fine tuners enable the performer to make small changes in the pitch of a string. At the scroll end, the strings wind around the wooden tuning pegs in the pegbox. The tuning pegs are tapered and fit into holes in the peg box. The tuning pegs are held in place by the friction of wood on wood. Strings may be made of metal or less commonly gut or gut wrapped in metal. Strings usually have a colored silk wrapping at both ends, for identification of the string (e.g., G string, D string, A string or E string) and to provide friction against the pegs. The tapered pegs allow friction to be increased or decreased by the player applying appropriate pressure along the axis of the peg while turning it.

Strings

Strings were first made of sheep gut (commonly known as catgut, which despite the name, did not come from cats), or simply gut, which was stretched, dried, and twisted. In the early years of the 20th century, strings were made of either gut or steel. Modern strings may be gut, solid steel, stranded steel, or various synthetic materials such as perlon, wound with various metals, and sometimes plated with silver. Most E strings are unwound, either plain or plated steel. Gut strings are not as common as they once were, but many performers use them to achieve a specific sound especially in historically informed performance of Baroque music. Strings have a limited lifetime. Eventually, when oil, dirt, corrosion, and rosin accumulate, the mass of the string can become uneven along its length. Apart from obvious things, such as the winding of a string coming undone from wear, players generally change a string when it no longer plays "true" (with good intonation on the harmonics), losing the desired tone, brilliance and intonation. String longevity depends on string quality and playing intensity.

Pitch range

A violin is tuned in fifths, in the notes G3, D4, A4, E5. The lowest note of a violin, tuned normally, is G3, or G below middle C (C4). (On rare occasions, the lowest string may be tuned down by as much as a fourth, to D3.) The highest note playable is less well defined: E7, the E two octaves above the open string (which is tuned to E5) may be considered a practical limit for orchestral violin parts,[26] but it is often possible to play higher, depending on the length of the fingerboard and the skill of the violinist. Yet higher notes (up to C8) can be sounded by stopping the string, reaching the limit of the fingerboard, and/or by using artificial harmonics.

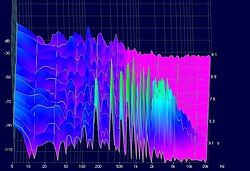

Acoustics

The arched shape, the thickness of the wood, and its physical qualities govern the sound of a violin. Patterns of the node made by sand or glitter sprinkled on the plates with the plate vibrated at certain frequencies, called Chladni patterns, are occasionally used by luthiers to verify their work before assembling the instrument.[27]

Sizes

Apart from the standard full (4⁄4) size, violins are also made in so-called fractional sizes of 7⁄8, 3⁄4, 1⁄2, 1⁄4, 1⁄8, 1⁄10, 1⁄16, 1⁄32 and even 1⁄64. These smaller instruments are commonly used by young players whose fingers are not long enough to reach the correct positions on full-sized instruments.

While related in some sense to the dimensions of the instruments, the fractional sizes are not intended to be literal descriptions of relative proportions. For example, a 3⁄4-sized instrument is not three-quarters the length of a full size instrument. The body length (not including the neck) of a full-size, or 4⁄4, violin is 356 mm (14.0 in), smaller in some 17th-century models. A 3⁄4 violin's body length is 335 mm (13.2 in), and a 1⁄2 size is 310 mm (12.2 in). With the violin's closest family member, the viola, size is specified as body length in inches or centimeters rather than fractional sizes. A full-size viola averages 40 cm (16 in). However, each individual adult will determine which size of viola to use.

Occasionally, an adult with a small frame may use a so-called 7⁄8 size violin instead of a full-size instrument. Sometimes called a lady's violin, these instruments are slightly shorter than a full size violin, but tend to be high-quality instruments capable of producing a sound comparable to that of fine full size violins. The sizes of 5-string violins may differ from the normal 4-string.

Mezzo violin

The instrument which corresponds to the violin in the violin octet is the mezzo violin, tuned the same as a violin but with a slightly longer body. The strings of the mezzo violin are the same length as those of the standard violin. This instrument is not in common use.[28]

Tuning

Violins are tuned by turning the pegs in the pegbox under the scroll or by adjusting the fine tuner screws at the tailpiece. All violins have pegs; fine tuners (also called fine adjusters) are optional. Most fine tuners consist of a metal screw that moves a lever attached to the string end. They permit very small pitch adjustments much more easily than the pegs. Turning a fine tuner clockwise causes the pitch to become sharper (as the string is under more tension), and turning it counterclockwise, the pitch becomes flatter (as the string is under less tension). Fine tuners on all four of the strings are very helpful when using those with a steel core, and some players use them with synthetic strings. Since modern E strings are steel, a fine tuner is nearly always fitted for that string. Fine tuners are not used with gut strings, which are more elastic than steel or synthetic-core strings and do not respond adequately to the very small movements of fine tuners.

To tune a violin, the A string is first tuned to a standard pitch (usually A=440 Hz). (When accompanying or playing with a fixed-pitch instrument such as a piano or accordion, the violin tunes to the corresponding note on that instrument rather than to any other tuning reference. The oboe is generally the instrument used to tune orchestras where violins are present since its sound is penetrating and can be heard over the other woodwinds.) The other strings are then tuned against each other in intervals of perfect fifths by bowing them in pairs. A minutely higher tuning is sometimes employed for solo playing to give the instrument a brighter sound; conversely, Baroque music is sometimes played using lower tunings to make the violin's sound more gentle. After tuning, the instrument's bridge may be examined to ensure that it is standing straight and centered between the inner nicks of the f-holes; a crooked bridge may significantly affect the sound of an otherwise well-made violin.

After extensive playing, the tuning pegs and their holes can become worn, making the pegs more likely to slip under tension. A slipping peg leads to the pitch of the string dropping somewhat, or if the peg becomes completely loose, to the string completely losing tension. A violin in which the tuning pegs are slipping needs to be repaired by a luthier or violin repairperson. Peg dope or peg compound, used regularly, can delay the onset of such wear while allowing the pegs to turn smoothly.

The tuning G–D–A–E is used for most violin music, including Classical music, jazz, and folk music. Other tunings are occasionally employed; the G string, for example, can be tuned up to A. The use of nonstandard tunings in classical music is known as scordatura; in some folk styles, it is called cross tuning. One famous example of scordatura in classical music is Camille Saint-Saëns' Danse Macabre, where the solo violin's E string is tuned down to E♭ to impart an eerie dissonance to the composition. Other examples are the third movement of Contrasts, by Béla Bartók, where the E string is tuned down to E♭ and the G tuned to a G♯, Niccolò Paganini's First Violin Concerto, where all four strings are designated to be tuned a semitone higher, and the Mystery Sonatas by Biber, in which each movement has different scordatura tuning.

In Indian classical music and Indian light music, the violin is likely to be tuned to D♯–A♯–D♯–A♯ in the South Indian style. As there is no concept of absolute pitch in Indian classical music, musicians can use any convenient tuning to maintain these relative pitch intervals between the strings. Another prevalent tuning with these intervals is B♭–F–B♭–F, which corresponds to Sa–Pa–Sa–Pa in the Indian carnatic classical music style. In the North Indian Hindustani style, the tuning is usually Pa-Sa-Pa-Sa instead of Sa–Pa–Sa–Pa. This could correspond to F–B♭–F–B♭, for instance. In Iranian classical music and Iranian light music, the violin has different tunings in each Dastgah; it is likely to be tuned (E–A–E–A) in Dastgah-h Esfahan or in Dastgāh-e Šur is (E–A–D–E) and (E–A–E–E), in Dastgāh-e Māhur is (E–A–D–A). In Arabic classical music, the A and E strings are lowered by a whole step, i.e. G–D–G–D. This is to ease playing Arabic maqams, especially those containing quarter tones.

While most violins have four strings, there are violins with additional strings, some with as many as seven. Seven is generally thought to be the maximum number of strings practical on a bowed string instrument; with more than seven strings, it would be impossible to play any particular inner string individually with the bow. Violins with seven strings are very rare. The extra strings on such violins typically are lower in pitch than the G-string; these strings are usually tuned (going from the highest added string to the lowest) to C, F, and B♭. If the instrument's playing length, or string length from nut to bridge, is equal to that of an ordinary full-scale violin; i.e., a bit less than 13 inches (33 cm), then it may be properly termed a violin. Some such instruments are somewhat longer and should be regarded as violas. Violins with five strings or more are typically used in jazz or folk music. Some custom-made instruments have extra strings which are not bowed, but which sound sympathetically, due to the vibrations of the bowed strings.

Bows

A violin is usually played using a bow consisting of a stick with a ribbon of horsehair strung between the tip and frog (or nut, or heel) at opposite ends. A typical violin bow may be 75 cm (30 in) overall, and weigh about 60 g (2.1 oz). Viola bows may be about 5 mm (0.20 in) shorter and 10 g (0.35 oz) heavier. At the frog end, a screw adjuster tightens or loosens the hair. Just forward of the frog, a leather thumb cushion (called the grip) and a winding protect the stick and provide a secure hold for the player's hand. Traditional windings are of wire (often silver or plated silver), silk, or baleen ("whalebone", now substituted by alternating strips of tan and black plastic.) Some fiberglass student bows employ a plastic sleeve as both grip and winding.

Bow hair traditionally comes from the tail of a grey male horse (which has predominantly white hair). Some cheaper bows use synthetic fiber. Solid rosin is rubbed onto the hair, to render it slightly sticky; when the bow is drawn across a string, the friction between them makes the string vibrate. Traditional materials for the more costly bow sticks include snakewood, and brazilwood (which is also known as Pernambuco wood). Some recent bow design innovations use carbon fiber (CodaBows) for the stick, at all levels of craftsmanship. Inexpensive bows for students are made of less costly timbers, or from fiberglass (Glasser).

Playing

Posture

The violin is played either seated or standing up. Solo players (whether playing alone, with a piano or with an orchestra) play mostly standing up (unless prevented by a physical disability such as in the case of Itzhak Perlman). In contrast, in the orchestra and in chamber music it is usually played seated. In the 2000s and 2010s, some orchestras performing Baroque music (such as the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra) have had all of their violins and violas, solo and ensemble, perform standing up.

The standard way of holding the violin is with the left side of the jaw resting on the chinrest of the violin, and supported by the left shoulder, often assisted by a shoulder rest (or a sponge and an elastic band for younger players who struggle with shoulder rests). The jaw and the shoulder must hold the violin firmly enough to allow it to remain stable when the left hand goes from a high position (a high pitched note far up on the fingerboard) to a low one (nearer to the pegbox). In the Indian posture, the stability of the violin is guaranteed by its scroll resting on the side of the foot.

While teachers point out the vital importance of good posture both for the sake of the quality of the playing and to reduce the chance of repetitive strain injury, advice as to what good posture is and how to achieve it differs in details. However, all insist on the importance of a natural relaxed position without tension or rigidity. Things which are almost universally recommended are keeping the left wrist straight (or very nearly so) to allow the fingers of the left hand to move freely and to reduce the chance of injury and keeping either shoulder in a natural relaxed position and avoiding raising either of them in an exaggerated manner. This, like any other unwarranted tension, would limit freedom of motion, and increase the risk of injury.

Hunching can hamper good playing because it throws the body off balance and makes the shoulders rise. Another sign that comes from unhealthy tension is pain in the left hand, which indicates too much pressure when holding the violin.

Left hand and pitch production

The left hand determines the sounding length of the string, and thus the pitch of the string, by "stopping" it (pressing it) against the fingerboard with the fingertips, producing different pitches. As the violin has no frets to stop the strings, as is usual with the guitar, the player must know exactly where to place the fingers on the strings to play with good intonation (tuning). Beginning violinists play open strings and the lowest position, nearest to the nut. Students often start with relatively easy keys, such as A Major and G major. Students are taught scales and simple melodies. Through practice of scales and arpeggios and ear training, the violinist's left hand eventually "finds" the notes intuitively by muscle memory.

Beginners sometimes rely on tapes placed on the fingerboard for proper left hand finger placement, but usually abandon the tapes quickly as they advance. Another commonly used marking technique uses dots of white-out on the fingerboard, which wear off in a few weeks of regular practice. This practice, unfortunately, is used sometimes in lieu of adequate ear-training, guiding the placement of fingers by eye and not by ear. Especially in the early stages of learning to play, the so-called "ringing tones" are useful. There are nine such notes in first position, where a stopped note sounds a unison or octave with another (open) string, causing it to resonate sympathetically. Students often use these ringing tones to check the intonation of the stopped note by seeing if it is harmonious with the open string. For example, when playing the stopped pitch "A" on the G string, the violinist could play the open D string at the same time, to check the intonation of the stopped "A". If the "A" is in tune, the "A" and the open D string should produce a harmonious perfect fourth.

Violins are tuned in perfect fifths, like all the orchestral strings (violin, viola, cello) except the double bass, which is tuned in perfect fourths. Each subsequent note is stopped at a pitch the player perceives as the most harmonious, "when unaccompanied, [a violinist] does not play consistently in either the tempered or the natural [just] scale, but tends on the whole to conform with the Pythagorean scale."[29] When violinists are playing in a string quartet or a string orchestra, the strings typically "sweeten" their tuning to suit the key they are playing in. When playing with an instrument tuned to equal temperament, such as a piano, skilled violinists adjust their tuning to match the equal temperament of the piano to avoid discordant notes.

The fingers are conventionally numbered 1 (index) through 4 (little finger) in music notation, such as sheet music and etude books. Especially in instructional editions of violin music, numbers over the notes may indicate which finger to use, with 0 or O indicating an open string. The chart to the right shows the arrangement of notes reachable in first position. Not shown on this chart is the way the spacing between note positions becomes closer as the fingers move up (in pitch) from the nut. The bars at the sides of the chart represent the usual possibilities for beginners' tape placements, at 1st, high 2nd, 3rd, and 4th fingers.

Positions

The placement of the left hand on the fingerboard is characterized by "positions". First position, where most beginners start (although some methods start in third position), is the most commonly used position in string music. Music composed for beginning youth orchestras is often mostly in first position. The lowest note available in this position in standard tuning is an open G3; the highest note in first position is played with the fourth finger on the E-string, sounding a B5. Moving the hand up the neck, the first finger takes the place of the second finger, bringing the player into second position. Letting the first finger take the first-position place of the third finger brings the player to third position, and so on. A change of positions, with its associated movement of the hand, is referred to as a shift, and effective shifting maintaining accurate intonation and a smooth legato (connected) sound is a key element of technique at all levels. Often a "guide finger" is used; the last finger to play a note in the old position continuously lightly touches the string during the course of the shift to end up on its correct place in the new position. In elementary shifting exercises the "guide finger" is often voiced while gliding up or down the string, so the player can establish correct placement by ear. Outside of these exercises it should rarely be audible (unless the performer is consciously applying a portamento effect for expressive reasons).

In the course of a shift in low positions, the thumb of the left hand moves up or down the neck of the instrument so as to remain in the same position relative to the fingers (though the movement of the thumb may occur slightly before, or slightly after, the movement of the fingers). In such positions, the thumb is often thought of as an 'anchor' whose location defines what position the player is in. In very high positions, the thumb is unable to move with the fingers as the body of the instrument gets in the way. Instead, the thumb works around the neck of the instrument to sit at the point at which the neck meets the right bout of the body, and remains there while the fingers move between the high positions.

A note played outside of the normal compass of a position, without any shift, is referred to as an extension. For instance, in third position on the A string, the hand naturally sits with the first finger on D♮ and the fourth on either G♮ or G♯. Stretching the first finger back down to a C♯, or the fourth finger up to an A♮, forms an extension. Extensions are commonly used where one or two notes are slightly out of an otherwise solid position, and give the benefit of being less intrusive than a shift or string crossing. The lowest position on the violin is referred to as "half position". In this position the first finger is on a "low first position" note, e.g. B♭ on the A string, and the fourth finger is in a downward extension from its regular position, e.g. D♮ on the A string, with the other two fingers placed in between as required. As the position of the thumb is typically the same in "half position" as in first position, it is better thought of as a backwards extension of the whole hand than as a genuine position.

The upper limit of the violin's range is largely determined by the skill of the player, who may easily play more than two octaves on a single string, and four octaves on the instrument as a whole. Position names are mostly used for the lower positions and in method books and etudes; for this reason, it is uncommon to hear references to anything higher than seventh position. The highest position, practically speaking, is 13th position. Very high positions are a particular technical challenge, for two reasons. Firstly, the difference in location of different notes becomes much narrower in high positions, making the notes more challenging to locate and in some cases to distinguish by ear. Secondly, the much shorter sounding length of the string in very high positions is a challenge for the right arm and bow in sounding the instrument effectively. The finer (and more expensive) an instrument, the better able it is to sustain good tone right to the top of the fingerboard, at the highest pitches on the E string.

All notes (except those below the open D) can be played on more than one string. This is a standard design feature of stringed instruments; however, it differs from the piano, which has only one location for each of its 88 notes. For instance, the note of open A on the violin can be played as the open A, or on the D string (in first to fourth positions) or even on the G string (very high up in sixth to ninth positions). Each string has a different tone quality, because of the different weights (thicknesses) of the strings and because of the resonances of other open strings. For instance, the G string is often regarded as having a very full, sonorous sound which is particularly appropriate to late Romantic music. This is often indicated in the music by the marking, for example, sul G or IV (a Roman numeral indicating to play on the fourth string; by convention, the strings are numbered from thinnest, highest pitch (I) to the lowest pitch (IV)). Even without an explicit instructions in the score, an advanced violinist will use her/his discretion and artistic sensibility to select which string to play specific notes or passages.

Open strings

If a string is bowed or plucked without any finger stopping it, it is said to be an open string. This gives a different sound from a stopped string, since the string vibrates more freely at the nut than under a finger. Further, it is impossible to use vibrato fully on an open string (though a partial effect can be achieved by stopping a note an octave up on an adjacent string and vibrating that, which introduces an element of vibrato into the overtones). In the classical tradition, violinists will often use a string crossing or shift of position to allow them to avoid the change of timbre introduced by an open string, unless indicated by the composer. This is particularly true for the open E which is often regarded as having a harsh sound. However, there are also situations where an open string may be specifically chosen for artistic effect. This is seen in classical music which is imitating the drone of an organ (J. S. Bach, in his Partita in E for solo violin, achieved this), fiddling (e.g., Hoedown) or where taking steps to avoid the open string is musically inappropriate (for instance in Baroque music where shifting position was less common). In quick passages of scales or arpeggios an open E string may simply be used for convenience if the note does not have time to ring and develop a harsh timbre. In folk music, fiddling and other traditional music genres, open strings are commonly used for their resonant timbre.

Playing an open string simultaneously with a stopped note on an adjacent string produces a bagpipe-like drone, often used by composers in imitation of folk music. Sometimes the two notes are identical (for instance, playing a fingered A on the D string against the open A string), giving a ringing sort of "fiddling" sound. Playing an open string simultaneously with an identical stopped note can also be called for when more volume is required, especially in orchestral playing. Some classical violin parts have notes for which the composer requests the violinist to play an open string, because of the specific sonority created by an open string.

Double stops, triple stops, chords and drones

Double stopping is when two separate strings are stopped by the fingers and bowed simultaneously, producing two continuous tones (typical intervals include 3rds, 4ths, 5ths, 6ths, and octaves). Double-stops can be indicated in any position, though the widest interval that can be double-stopped naturally in one position is an octave (with the index finger on the lower string and the pinky finger on the higher string). Nonetheless, intervals of tenths or even more are sometimes required to be double-stopped in advanced repertoire, resulting in a stretched left-hand position with the fingers extended. The term "double stop" is often used to encompass sounding an open string alongside a fingered note as well, even though only one finger stops the string.

Where three or four simultaneous notes are indicated, the violinist will typically "split" the chord, choosing the lower one or two notes to play first before immediately continuing onto the upper one or two notes, with the natural resonance of the instrument producing an effect similar to if all four notes had been voiced simultaneously. In some circumstances, a "triple stop" is possible, where three notes across three strings can be voiced simultaneously. The bow will not naturally strike three strings at once, but if there is sufficient bow speed and pressure when the violinist "breaks" (sounds) a three note chord, the bow hair can be bent temporarily onto three strings, allowing each to sound simultaneously. This is accomplished with a heavy stroke, typically near the frog, and produces a loud and aggressive tone. Double stops in orchestra are occasionally marked divisi and divided between the players, with some division of the musicians playing the lower note and some division playing the higher note. Double stops (and divisi) are common in orchestral repertoire when the violins play accompaniment and another instrument or section plays melodically.

In some genres of historically informed performance (usually of Baroque music and earlier), neither split-chord nor triple-stop chords are thought to be appropriate; some violinists will arpeggiate all chords (including regular double stops), playing all or most notes individually as if they had been written as a slurred figure. However, with the development of modern violins, triple-stopping has become more natural due to the bridge being less curved. In some musical styles, a sustained open string drone can be played during a passage mainly written on an adjacent string, to provide a basic accompaniment. This is more often seen in folk traditions than in classical music.

Vibrato

Vibrato is a technique of the left hand and arm in which the pitch of a note varies subtly in a pulsating rhythm. While various parts of the hand or arm may be involved in the motion, the result is a movement of the fingertip bringing about a slight change in vibrating string length, which causes an undulation in pitch. Most violinists oscillate below the note, or lower in pitch from the actual note when using vibrato, since it is believed that perception favors the highest pitch in a varying sound.[32] Vibrato does little, if anything, to disguise an out-of-tune note; in other words, misapplied vibrato is a poor substitute for good intonation. Scales and other exercises meant to work on intonation are typically played without vibrato to make the work easier and more effective. Music students are often taught that unless otherwise marked in music, vibrato is assumed. However, this is only a trend; there is nothing on the sheet music that compels violinists to add vibrato.[citation needed] This can be an obstacle to a classically trained violinist wishing to play in a style that uses little or no vibrato at all, such as baroque music played in period style and many traditional fiddling styles.

Vibrato can be produced by a proper combination of finger, wrist and arm motions. One method, called hand vibrato (or wrist vibrato), involves rocking the hand back at the wrist to achieve oscillation. In contrast, another method, arm vibrato, modulates the pitch by movement at the elbow. A combination of these techniques allows a player to produce a large variety of tonal effects. The "when" and "what for" and "how much" of violin vibrato are artistic matters of style and taste, with different teachers, music schools and styles of music favouring different styles of vibrato. For example, overdone vibrato may become distracting. In acoustic terms, the interest that vibrato adds to the sound has to do with the way that the overtone mix[33] (or tone color, or timbre) and the directional pattern of sound projection change with changes in pitch. By "pointing" the sound at different parts of the room[34][35] in a rhythmic way, vibrato adds a "shimmer" or "liveliness" to the sound of a well-made violin. Vibrato is, in a large part, left to the discretion of the violinist. Different types of vibrato will bring different moods to the piece, and the varying degrees and styles of vibrato are often characteristics that stand out in well-known violinists.

Vibrato trill

A vibrato-like motion can sometimes be used to create a fast trill effect. To execute this effect, the finger above the finger stopping the note is placed very slightly off the string (firmly pressed against the finger stopping the string) and a vibrato motion is implemented. The second finger will lightly touch the string above the lower finger with each oscillation, causing the pitch to oscillate in a fashion that sounds like a mix between wide vibrato and a very fast trill. This gives a less defined transition between the higher and lower note, and is usually implemented by interpretative choice. This trill technique only works well for semi-tonal trills or trills in high positions (where the distance between notes is lessened), as it requires the trilling finger and the finger below it to be touching, limiting the distance that can be trilled. In very high positions, where the trilled distance is less than the width of the finger, a vibrato trill may be the only option for trill effects.

Harmonics

Lightly touching the string with a fingertip at a harmonic node, but without fully pressing the string, and then plucking or bowing the string, creates harmonics. Instead of the normal tone, a higher pitched note sounds. Each node is at an integer division of the string, for example half-way or one-third along the length of the string. A responsive instrument will sound numerous possible harmonic nodes along the length of the string. Harmonics are marked in music either with a little circle above the note that determines the pitch of the harmonic, or by diamond-shaped note heads. There are two types of harmonics: natural harmonics and artificial harmonics (also known as false harmonics).

Natural harmonics are played on an open string. The pitch of the open string when it is plucked or bowed is called the fundamental frequency. Harmonics are also called overtones or partials. They occur at whole-number multiples of the fundamental, which is called the first harmonic. The second harmonic is the first overtone (the octave above the open string), the third harmonic is the second overtone, and so on. The second harmonic is in the middle of the string and sounds an octave higher than the string's pitch. The third harmonic breaks the string into thirds and sounds an octave and a fifth above the fundamental, and the fourth harmonic breaks the string into quarters sounding two octaves above the first. The sound of the second harmonic is the clearest of them all, because it is a common node with all the succeeding even-numbered harmonics (4th, 6th, etc.). The third and succeeding odd-numbered harmonics are harder to play because they break the string into an odd number of vibrating parts and do not share as many nodes with other harmonics.

Artificial harmonics are more difficult to produce than natural harmonics, as they involve both stopping the string and playing a harmonic on the stopped note. Using the octave frame (the normal distance between the first and fourth fingers in any given position) with the fourth finger just touching the string a fourth higher than the stopped note produces the fourth harmonic, two octaves above the stopped note. Finger placement and pressure, as well as bow speed, pressure, and sounding point are all essential in getting the desired harmonic to sound. And to add to the challenge, in passages with different notes played as false harmonics, the distance between stopping finger and harmonic finger must constantly change, since the spacing between notes changes along the length of the string.

The harmonic finger can also touch at a major third above the pressed note (the fifth harmonic), or a fifth higher (a third harmonic). These harmonics are less commonly used; in the case of the major third, both the stopped note and touched note must be played slightly sharp otherwise the harmonic does not speak as readily. In the case of the fifth, the stretch is greater than is comfortable for many violinists. In the general repertoire fractions smaller than a sixth are not used. However, divisions up to an eighth are sometimes used and, given a good instrument and a skilled player, divisions as small as a twelfth are possible. There are a few books dedicated solely to the study of violin harmonics. Two comprehensive works are Henryk Heller's seven-volume Theory of Harmonics, published by Simrock in 1928, and Michelangelo Abbado's five-volume Tecnica dei suoni armonici published by Ricordi in 1934.

Elaborate passages in artificial harmonics can be found in virtuoso violin literature, especially of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Two notable examples of this are an entire section of Vittorio Monti's Csárdás and a passage towards the middle of the third movement of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto. A section of the third movement of Paganini's Violin Concerto No. 1 consists of double-stopped thirds in harmonics.

When strings are worn, dirty and old, the harmonics may no longer be accurate in pitch. For this reason, violinists change their strings regularly.

Right hand and tone color

The strings may be sounded by drawing the hair of the bow held by the right hand across them (arco) or by plucking them (pizzicato) most often with the right hand. In some cases, the violinist will pluck strings with the left hand. This is done to facilitate transitions from pizzicato to arco playing. It is also used in some virtuoso showpieces. Left hand pizzicato is usually done on open strings. Pizzicato is used on all of the violin family instruments; however, the systematic study of advanced pizzicato techniques is most developed in jazz bass, a style in which the instrument is almost exclusively plucked.

The right arm, hand, and bow and the bow speed are responsible for tone quality, rhythm, dynamics, articulation, and most (but not all) changes in timbre. The player draws the bow over the string, causing the string to vibrate and produce a sustained tone. The bow is a wooden stick with tensioned horsetail hair, which has been rosined with a bar of rosin. The natural texture of the horsehair and the stickiness of the rosin help the bow to "grip" the string, and thus when the bow is drawn over the string, the bow causes the string to sound a pitch.

Bowing can be used to produce long sustained notes or melodies. With a string section, if the players in a section change their bows at different times, a note can seem to be endlessly sustainable. As well, the bow can be used to play short, crisp little notes, such as repeated notes, scales and arpeggios, which provide a propulsive rhythm in many styles of music.

Bowing techniques

The most essential part of bowing technique is the bow grip. It is usually with the thumb bent in the small area between the frog and the winding of the bow. The other fingers are spread somewhat evenly across the top part of the bow. The pinky finger is curled with the tip of the finger placed on the wood next to the screw. The violin produces louder notes with greater bow speed or more weight on the string. The two methods are not equivalent, because they produce different timbres; pressing down on the string tends to produce a harsher, more intense sound. One can also achieve a louder sound by placing the bow closer to the bridge.

The sounding point where the bow intersects the string also influences timbre (or "tone colour"). Playing close to the bridge (sul ponticello) gives a more intense sound than usual, emphasizing the higher harmonics; and playing with the bow over the end of the fingerboard (sul tasto) makes for a delicate, ethereal sound, emphasizing the fundamental frequency. Shinichi Suzuki referred to the sounding point as the Kreisler highway; one may think of different sounding points as lanes in the highway.

Various methods of attack with the bow produce different articulations. There are many bowing techniques that allow for every range of playing style. Many teachers, players, and orchestras spend a lot of time developing techniques and creating a unified technique within the group. These techniques include legato-style bowing (a smooth, connected, sustained sound suitable for melodies), collé, and a variety of bowings which produce shorter notes, including ricochet, sautillé, martelé, spiccato, and staccato.

Pizzicato

A note marked pizz. (abbreviation for pizzicato) in the written music is to be played by plucking the string with a finger of the right hand rather than by bowing. (The index finger is most commonly used here.) Sometimes in orchestra parts or virtuoso solo music where the bow hand is occupied (or for show-off effect), left-hand pizzicato will be indicated by a + (plus sign) below or above the note. In left-hand pizzicato, two fingers are put on the string; one (usually the index or middle finger) is put on the correct note, and the other (usually the ring finger or little finger) is put above the note. The higher finger then plucks the string while the lower one stays on, thus producing the correct pitch. By increasing the force of the pluck, one can increase the volume of the note that the string is producing. Pizzicato is used in orchestral works and in solo showpieces. In orchestral parts, violinists often have to make very quick shifts from arco to pizzicato, and vice versa.

Col legno

A marking of col legno (Italian for "with the wood") in the written music calls for striking the string(s) with the stick of the bow, rather than by drawing the hair of the bow across the strings. This bowing technique is somewhat rarely used, and results in a muted percussive sound. The eerie quality of a violin section playing col legno is exploited in some symphonic pieces, notably the "Witches' Dance" of the last movement of Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique. Saint-Saëns's symphonic poem Danse Macabre includes the string section using the col legno technique to imitate the sound of dancing skeletons. "Mars" from Gustav Holst's "The Planets" uses col legno to play a repeated rhythm in 5

4 time signature. Benjamin Britten's The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra demands its use in the "Percussion" Variation. Dmitri Shostakovich uses it in his Fourteenth Symphony in the movement 'At the Sante Jail'. Some violinists, however, object to this style of playing as it can damage the finish and impair the value of a fine bow, but most of such will compromise by using a cheap bow for at least the duration of the passage in question.

Detaché

A smooth and even stroke during which bow speed and weight are the same from beginning of the stroke to the end.[36]

Martelé

Literally hammered, a strongly accented effect produced by releasing each bowstroke forcefully and suddenly. Martelé can be played in any part of the bow. It is sometimes indicated in written music by an arrowhead.

Tremolo

Tremolo is the very rapid repetition (typically of a single note, but occasionally of multiple notes), usually played at the tip of the bow. Tremolo is marked with three short, slanted lines across the stem of the note. Tremolo is often used as a sound effect in orchestral music, particularly in the Romantic music era (1800-1910) and in opera music.

Mute or sordino

Attaching a small metal, rubber, leather, or wooden device called a mute, or sordino, to the bridge of the violin gives a softer, more mellow tone, with fewer audible overtones; the sound of an entire orchestral string section playing with mutes has a hushed quality. The mute changes both the loudness and the timbre ("tone colour") of a violin. The conventional Italian markings for mute usage are con sord., or con sordino, meaning 'with mute'; and senza sord., meaning 'without mute'; or via sord., meaning 'mute off'.

Larger metal, rubber, or wooden mutes are widely available, known as practice mutes or hotel mutes. Such mutes are generally not used in performance, but are used to deaden the sound of the violin in practice areas such as hotel rooms. (For practicing purposes there is also the mute violin, a violin without a sound box.) Some composers have used practice mutes for special effect, for example, at the end of Luciano Berio's Sequenza VIII for solo violin.

Musical styles

Classical music

Since the Baroque era, the violin has been one of the most important of all instruments in classical music, for several reasons. The tone of the violin stands out above other instruments, making it appropriate for playing a melody line. In the hands of a good player, the violin is extremely agile, and can execute rapid and difficult sequences of notes.

Violins make up a large part of an orchestra, and are usually divided into two sections, known as the first and second violins. Composers often assign the melody to the first violins, typically a more difficult part using higher positions. In contrast, second violins play harmony, accompaniment patterns or the melody an octave lower than the first violins. A string quartet similarly has parts for first and second violins, as well as a viola part, and a bass instrument, such as the cello or, rarely, the double bass.

Jazz

The earliest references to jazz performance using the violin as a solo instrument are documented during the first decades of the 20th century. Joe Venuti, one of the first jazz violinists, is known for his work with guitarist Eddie Lang during the 1920s. Since that time there have been many improvising violinists including Stéphane Grappelli, Stuff Smith, Eddie South, Regina Carter, Johnny Frigo, John Blake, Adam Taubitz, Leroy Jenkins, and Jean-Luc Ponty. While not primarily jazz violinists, Darol Anger and Mark O'Connor have spent significant parts of their careers playing jazz. The Swiss-Cuban violinist Yilian Cañizares mixes jazz with Cuban music.[37]

Violins also appear in ensembles supplying orchestral backgrounds to many jazz recordings.

Indian classical music

The Indian violin, while essentially the same instrument as that used in Western music, is different in some senses.[38] The instrument is tuned so that the IV and III strings (G and D on a western-tuned violin) and the II and I (A and E) strings are sa–pa (do–sol) pairs and sound the same but are offset by an octave, resembling common scordatura or fiddle cross-tunings such as G3–D4–G4–D5 or A3–E4–A4–E5. The tonic sa (do) is not fixed, but variably tuned to accommodate the vocalist or lead player. The way the musician holds the instrument varies from Western to Indian music. In Indian music the musician sits on the floor cross-legged with the right foot out in front of them. The scroll of the instrument rests on the foot. This position is essential to playing well due to the nature of Indian music. The hand can move all over the fingerboard and there is no set position for the left hand, so it is important for the violin to be in a steady, unmoving position.

Popular music

Up through at least the 1970s, most types of popular music used bowed string sections. They were extensively used in popular music throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. With the rise of swing music, however, from 1935 to 1945, the string sound was often used to add to the fullness of big band music. Following the swing era, from the late 1940s to the mid-1950s, strings began to be revived in traditional pop music. This trend accelerated in the late 1960s, with a significant revival of the use of strings, especially in soul music. Popular Motown recordings of the late 1960s and 1970s relied heavily on strings as part of their trademark texture.

With the rise of electronically created music in the 1980s, violins declined in use, as synthesized string sounds played by a keyboardist with a synthesizer took their place. However, while the violin has had very little usage in mainstream rock music, it has some history in progressive rock (e.g., Electric Light Orchestra, King Crimson, Kansas, Gentle Giant). The instrument has a stronger place in modern jazz fusion bands, notably The Corrs.

The popularity of crossover music beginning in the last years of the 20th century has brought the violin back into the popular music arena, with both electric and acoustic violins being used by popular bands. Dave Matthews Band features violinist Boyd Tinsley. The Flock featured violinist Jerry Goodman who later joined the jazz-rock fusion band, The Mahavishnu Orchestra. James' Saul Davies, who is also a guitarist, was enlisted by the band as a violinist.

The folk metal band Ithilien use violin extensively along their discography.[39] Progressive metal band Ne Obliviscaris feature a violin player, Tim Charles, in their line-up.[40]

Independent artists, such as Owen Pallett, The Shondes, and Andrew Bird, have also spurred increased interest in the instrument.[41] Indie bands have often embraced new and unusual arrangements, allowing them more freedom to feature the violin than many mainstream musical artists. Lindsey Stirling plays the violin in conjunction with electronic/dubstep/trance rifts and beats.[42]

Eric Stanley improvises on the violin with hip hop music/pop/classical elements and instrumental beats.[43][44] The successful indie rock and baroque pop band Arcade Fire use violins extensively in their arrangements.[45]

Folk music and fiddling

Like many other instruments used in classical music, the violin descends from remote ancestors that were used for folk music. Following a stage of intensive development in the late Renaissance, largely in Italy, the violin had improved (in volume, tone, and agility), to the point that it not only became a very important instrument in art music, but proved highly appealing to folk musicians as well, ultimately spreading very widely, sometimes displacing earlier bowed instruments. Ethnomusicologists have observed its widespread use in Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

When played as a folk instrument, the violin is usually referred to in English as a fiddle (although the term fiddle can be used informally no matter what the genre of music). Worldwide, there are various stringed instruments such as the wheel fiddle and Apache fiddle that are also called "fiddles". Fiddle music differs from classical in that the tunes are generally considered dance music,[46] and various techniques, such as droning, shuffling, and ornamentation specific to particular styles are used. In many traditions of folk music, the tunes are not written but are memorized by successive generations of musicians and passed on[46] in what is known as the oral tradition. Many old-time pieces call for cross-tuning, or using tunings other than standard GDAE. Some players of American styles of folk fiddling (such as bluegrass or old-time) have their bridge's top edge cut to a slightly flatter curve, making techniques such as a "double shuffle" less taxing on the bow arm, as it reduces the range of motion needed for alternating between double stops on different string pairs. Fiddlers who use solid steel core strings may prefer to use a tailpiece with fine tuners on all four strings, instead of the single fine tuner on the E string used by many classical players.

Arabic music

As well as the Arabic rababah, the violin has been used in Arabic music.

Electric violins

Electric violins have a magnetic or piezoelectric pickup that converts string vibration to an electric signal. A patch cable or wireless transmitter sends the signal to an amplifier of a PA system. Electric violins are usually constructed as such, but a pickup can be added to a conventional acoustic violin. An electric violin with a resonating body that produces listening-level sound independently of the electric elements can be called an electro-acoustic violin. To be effective as an acoustic violin, electro-acoustic violins retain much of the resonating body of the violin, and often resemble an acoustic violin or fiddle. The body may be finished in bright colors and made from alternative materials to wood. These violins may need to be hooked up to an instrument amplifier or PA system. Some types come with a silent option that allows the player to use headphones that are hooked up to the violin. The first specially built electric violins date back to 1928 and were made by Victor Pfeil, Oskar Vierling, George Eisenberg, Benjamin Miessner, George Beauchamp, Hugo Benioff and Fredray Kislingbury. These violins can be plugged into effect units, just like an electric guitar, including distortion, wah-wah pedal and reverb. Since electric violins do not rely on string tension and resonance to amplify their sound they can have more strings. For example, five-stringed electric violins are available from several manufacturers, and a seven string electric violin (with three lower strings encompassing the cello's range) is also available.[47] The majority of the first electric violinists were musicians playing jazz fusion (e.g., Jean-Luc Ponty) and popular music.

Violin authentication

Violin authentication is the process of determining the maker and manufacture date of a violin. This can be an important process as significant value may be attached to violins made either by specific makers or at specific times and locations. Analysis on design, model, wood characteristics, and varnish texture can be used to authenticate a violin.[48] Forgery and other methods of fraudulent misrepresentation can be used to inflate the value of an instrument.

See also

Notes

- ^ In short, the difference between a fiddle and a violin is simply in the style of music they are used to play. Violin players typically perform classical music, such as in orchestras and string quartets. Fiddle players, on the other hand, typically perform folk music, country music, and other types of traditional music.

References

- ^ Singh, Jhujhar. "Interview: Kala Ramnath". News X. YouTube. Archived from the original on 2014-06-03. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ Allen, Edward Heron (1914). Violin-making, as it was and is: Being a Historical, Theoretical, and Practical Treatise on the Science and Art of Violin-making, for the Use of Violin Makers and Players, Amateur and Professional. Preceded by An Essay on the Violin and Its Position as a Musical Instrument. E. Howe. Accessed 5 September 2015.

- ^ Choudhary, S.Dhar (2010). The Origin and Evolution of Violin as a Musical Instrument and Its Contribution to the Progressive Flow of Indian Classical Music: In search of the historical roots of violin. Ramakrisna Vedanta Math. ISBN 978-9380568065. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ Belluck, Pam (April 7, 2014). "A Strad? Violinists Can't Tell". New York Times. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ Joyce, Christopher (2012). "Double-Blind Violin Test: Can You Pick The Strad?". NPR. Retrieved 2012-01-02.

- ^ a b "Violin". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Viola". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ a b c "Fiddle". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ The Silk Road: Connecting Cultures, Creating Trust, Silk Road Story 2: Bowed Instruments, Smithsonian Center for Folk life and Cultural Heritage [1] Archived 2008-10-13 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 2008-09-26)

- ^ Hoffman, Miles (1997). The NPR Classical Music Companion: Terms and Concepts from A to Z. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0618619450.

- ^ a b Grillet 1901, p. 29

- ^ Margaret J. Kartomi: On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology, University of Chicago Press, 1990

- ^ The Cambridge Companion to the Cello

- ^ Schlesinger, Kathleen (May 29, 1914). "The Precursors of the Violin Family: Records, Researches & Studies". W. Reeves. p. 221 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sandys, William; Forster, Simon Andrew (May 29, 1864). "The history of the violin, and other instruments played on with the bow from the remotest times to the present. Also, an account of the principal makers, English and foreign, with numerous illustrations. By William Sandys and Simon Andrew Forster". London W. Reeves. p. 28 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Riemann, Hugo (May 29, 1892). "Catechism of musical history". Augener & Company, printed in Germany. p. 27 – via Google Books.

- ^ Arkenberg, Rebecca (October 2002). "Renaissance Violins". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2006-09-22.

- ^ Deverich, Robin Kay (2006). "Historical Background of the Violin". ViolinOnline.com. Retrieved 2006-09-22.

- ^ Bartruff, William. "The History of the Violin". Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2006-09-22.

- ^ It is now in the Vestlandske Kunstindustrimuseum in Bergen, Norway.

- ^ "Violin by Antonio Stradivari, 1716 (Messiah; la Messie, Salabue)". Cozio.com. Archived from the original on 2008-10-08. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (2017). The Oxford Dictionary of Music. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Pio Stefano (2012). Viol and Lute Makers of Venice 1490 -1630. Venice, Italy: Venice Research. p. 441. ISBN 9788890725203.

- ^ Perras, Richard. "Violin changes by 1800". Retrieved 2006-10-29.

- ^ "Stradivarius violin sold for £9.8m at charity auction". BBC News. 2011-06-21. Retrieved 2011-06-21.

- ^ Piston, Walter (1955). Orchestration, p.45.

- ^ Laird, Paul R. "Carleen Maley Hutchins' Work With Saunders". Violin Society of America. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ The New Violin Family Association, Inc (2020-04-04). "The New Violin Family". The New Violin Family.

- ^ Seashore, Carl (1938). Psychology of Music, 224. quote in Kolinski, Mieczyslaw (Summer - Autumn, 1959). "A New Equidistant 12-Tone Temperament", p.210, Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 12, No. 2/3, pp. 210-214.

- ^ Eaton, Louis (1919). The Violin. Jacobs' Band Monthly, Volume 4. p. 52. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ Bissing, Petrowitsch. Cultivation of the Violin Vibrato Tone. Central States Music Publishing Company. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ Applebaum, Samuel (1957). String Builder, Book 3: Teacher's Manual. New York: Alfred Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7579-3056-0.. "Now we will discipline the shaking of the left hand in the following manner: Shake the wrist slowly and evenly in 8th notes. Start from the original position and for the second 8th note the wrist is to move backward (toward the scroll). Do this in triplets, dotted 8ths and 16ths, and 16th notes. A week or two later, the vibrato may be started on the Violin. ... The procedure will be as follows: 1. Roll the finger tip from this upright position on the note, to slightly below the pitch of this note."

- ^ Schleske, Martin. "The psychoacoustic secret of vibrato". Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

Accordingly, the sound level of each harmonic will have a periodically fluctuating value due to the vibrato.

- ^ Curtin, Joseph (April 2000). "Weinreich and Directional Tone Colour". Strad Magazine. Archived from the original on May 29, 2009. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

In the case of string instruments, however, not only are they strongly directional, but the pattern of their directionality changes very rapidly with frequency. If you think of that pattern at a given frequency as beacons of sound, like the quills of a porcupine, then even the slight changes in pitch created by vibrato can cause those quills to be continually undulating.

- ^ Weinreich, Gabriel (December 16, 1996). "Directional tone color" (PDF). Acoustical Society of America.

The effect can be visualized in terms of a number of highly directional sound beacons, all of which the vibrato causes to undulate back and forth in a coherent and highly organized fashion. It is obvious that such a phenomenon will help immensely in fusing sounds of the differently directed partials into a single auditory stream; one may even speculate that it is a reason why vibrato is used so universally by violinists—as compared to wind players, from the sound of whose instruments directional tone color is generally absent.

- ^ Fischer, Simon (1999). "Detache". Strad. 110: 638 – via Music Index.

- ^ "Die Sängerin und Geigerin Yilian Cañizares in Moods". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 16 September 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Suryasarathi (December 10, 2017). "Violin virtuoso Dr L Subramaniam on how Indian classical music took on the world stage". First Post.

- ^ "Ithilien - discography, line-up, biography, interviews, photos". www.spirit-of-metal.com. Retrieved 2017-03-12.

- ^ "Ne Obliviscaris". Facebook.

- ^ Golden, Brian (December 5, 2017). "Andrew Bird Brings His Sweeping Symphony of Sounds to Chicago". Chicago Magazine.

- ^ Self, Brooke (April 9, 2011). "Lindsey Stirling—hip hop violinist". Her Campus. Archived from the original on 2014-12-05.

- ^ Tietjen, Alexa. "Get Your Life From This Violin Freestyle Of Fetty Wap's "Trap Queen"". vh1.com. VH1. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ Martinez, Marc (October 3, 2010). "Eric Stanley: Hip Hop Violinist". Fox 10 News (Interview). Phoenix: KTSP-TV. Archived from the original on 2021-10-29. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ "Arcade Fire – 10 of the best". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- ^ a b Harris, Rodger (2009). "Fiddling". okhistory.org. The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "7String Violin Harlequin finish". Jordan Music. Archived from the original on 2009-02-27. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ^ Institution, Smithsonian. "General Information on Violin Authentication and Appraisals". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

Bibliography

- Viol and Lute Makers of Venice 1490–1630, by Stefano Pio (2012), Venezia Ed. Venice research, ISBN 978-88-907252-0-3

- Violin and Lute Makers of Venice 1640–1760, by Stefano Pio (2004), Venezia Ed. Venice research, ISBN 978-88-907252-2-7

- Liuteri & Sonadori, Venice 1750–1870, by Stefano Pio (2002), Venezia Ed. Venice research, ISBN 978-88-907252-1-0

- The Violin Forms of Antonio Stradivari, by Stewart Pollens (1992), London: Peter Biddulph. ISBN 0-9520109-0-9

- Principles of Violin Playing and Teaching, by Ivan Galamian (1999), Shar Products Co. ISBN 0-9621416-3-1

- The Contemporary Violin: Extended Performance Techniques, by Patricia and Allen Strange (2001), University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22409-4

- The Violin: Its History and Making, by Karl Roy (2006), ISBN 978-1-4243-0838-5

- The Fiddle Book, by Marion Thede (1970), Oak Publications. ISBN 0-8256-0145-2

- Latin Violin, by Sam Bardfeld, ISBN 0-9628467-7-5

- The Canon of Violin Literature, by Jo Nardolillo (2012), Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-7793-7

- The Violin Explained - Components Mechanism and Sound by James Beament (1992/1997), Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-816623-0

- Antonio Stradivari, his life and work, 1644-1737', by William Henry Hill; Arthur F Hill; Alfred Ebsworth Hill (1902/1963), Dover Publications. 1963. OCLC 172278. ISBN 0-486-20425-1

- An Encyclopedia of the Violin, by Alberto Bachmann (1965/1990), Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80004-7

- Violin - And Easy Guide, by Chris Coetzee (2003), New Holland Publishers. ISBN 1-84330-332-9

- The Violin, by Yehudi Menuhin (1996), Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-013623-2

- The Book of the Violin, edited by Dominic Gill (1984), Phaidon. ISBN 0-7148-2286-8

- Violin-Making as it was, and is, by Edward Heron-Allen (1885/1994), Ward Lock Limited. ISBN 0-7063-1045-4

- Violins & Violinists, by Franz Farga (1950), Rockliff Publishing Corporation Ltd.

- Viols, Violins and Virginals, by Jennifer A. Charlton (1985), Ashmolean Museum. ISBN 0-907849-44-X

- The Violin, by Theodore Rowland-Entwistle (1967/1974), Dover Publications. ISBN 0-340-05992-3

- The Early Violin and Viola, by Robin Stowell (2001), Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62555-6

- The Complete Luthier's Library. A Useful International Critical Bibliography for the Maker and the Connoisseur of Stringed and Plucked Instruments by Roberto Regazzi, Bologna: Florenus, 1990. ISBN 88-85250-01-7

- The Violin, by George Dubourg (1854), Robert Cocks & Co.

- Violin Technique and Performance Practice in the Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries, by Robin Stowell (1985), Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23279-1

- History of the Violin, by William Sandys and Simon Andrew (2006), Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-45269-7

- The Violin: A Research and Information Guide, by Mark Katz (2006), Routledge. ISBN 0-8153-3637-3

- Per gli occhi e 'l core. Strumenti musicali nell'arte by Flavio Dassenno, (2004) a complete survey of the brescian school defined by the last researches and documents.

- Gasparo da Salò architetto del suono by Flavio Dassenno, (2009) a catalogue of an exhibition that gives information on the famous master life and work, Comune di Salò, Cremonabooks, 2009.

- Grillet, Laurent (1901). Les ancetres du violon v.1. Paris.

Further reading

- Lalitha, Muthuswamy (2004). Violin techniques in Western and South Indian classical music: a comparative study. Sundeep Prakashan. ISBN 9788175741515. OCLC 57671835.

- Schoenbaum, David, The Violin: A Social History of the World's Most Versatile Instrument, New York, New York : W.W. Norton & Company, December 2012. ISBN 9780393084405.

- Templeton, David, Fresh Prince: Joshua Bell on composition, hyperviolins, and the future, Strings magazine, October 2002, No. 105.

- Young, Diana. A Methodology for Investigation of Bowed String Performance Through Measurement of Violin Bowing Technique. PhD Thesis. M.I.T., 2007.

External links

- English-speaking violin organizations

- Harrison, Robert William Frederick (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). pp. 102–107.

- The violin: provenance, value and appraisal

- Shipping guide for a string instrument and bow