Silent Way

The Silent Way is a language-teaching approach created by Caleb Gattegno that is notable for the 'silence' of the teacher. (Who is not actually mute, but who rarely, if ever, models language for the students.) Gattegno first described the approach in 1963, in his book Teaching Foreign Languages in Schools: The Silent Way.[1] Gattegno was critical of mainstream language education at the time, and he based the Silent Way on his general theories of education rather than on existing language pedagogy. It is usually regarded as an "alternative" language-teaching method; Cook groups it under "other styles",[2] Richards groups it under "alternative approaches and methods"[3] and Jin & Cortazzi group it under "Humanistic or Alternative Approaches".[4] Gattegno continued to develop and describe the Silent Way until his death in 1988.[5][6] Others have continued to develop the approach, particularly for intermediate and advanced students.[7]

The method emphasizes learner autonomy and active student participation. Silence is used as a tool to achieve this goal; the teacher uses a mixture of silence and gestures to focus students' attention, to elicit responses from them, and to encourage them to correct their own errors. Pronunciation is seen as important, with time spent on improving pronunciation as needed in each lesson. The Silent Way uses a structural syllabus and concentrates on teaching the uses of the functional vocabulary of the language. Translation and rote repetition are avoided, and the language is practiced in meaningful contexts. Evaluation is carried out by observation, and the teacher may never set a formal test.

One of the hallmarks of the Silent Way when used with beginners is the use of Cuisenaire rods, which can be used for anything from simple commands ("Take two red rods and give them to her.") to representing objects such as clocks and floor plans. The approach also employs a color code to help teach pronunciation; there is a sound-color chart which is used to teach the sounds of the language, colored word charts which are used for work on sentences, and colored Fidel charts which are used to teach spelling. While the Silent Way is not widely used in its original form, its ideas have been influential, especially in the teaching of pronunciation.

Background and principles

[edit]

Gattegno was an outsider to language education when Teaching Foreign Languages in Schools was first published in 1963. The book conspicuously lacked the names of most prominent language educators and linguists of the time, and for the decade following its publication Gattegno's works were only rarely cited in language education books and journals.[8] He was previously a designer of mathematics and reading programmes, and the use of color charts and colored Cuisenaire rods in the Silent Way grew directly out of this experience.[9]

Gattegno was openly sceptical of the role that the linguistic theory of his time had in language teaching. He felt that linguistic studies "may be a specialization, [that] carry with them a narrow opening of one's sensitivity and perhaps serve very little towards the broad end in mind".[10] The Silent Way was conceived as a special case of Gattegno's broader educational principles, which he had developed to solve general problems in learning, and which he had previously applied to the teaching of mathematics and of spelling in the mother tongue. Broadly, these principles are:[11]

- Teachers should concentrate on how students learn, before considering how to teach

- Imitation and drill are not the primary means by which students learn

- Learning involves trial and error, deliberate experimentation, suspending judgement, and revising conclusions

- Learners can draw on everything that they already know

- The teacher must be careful not to interfere with the learning process

These principles situate the Silent Way in the tradition of discovery learning, that sees learning as a creative problem-solving activity guided by a teacher.[9]

Design and goals

[edit]The general goal of the Silent Way is to help beginning-level students gain basic fluency in the target language, with the ultimate aim being near-native language proficiency and good pronunciation.[12] An important part of this ability is being able to use the language for self-expression; students should be able to express their thoughts, feelings, and needs in the target language. In order to help them achieve this, teachers emphasize self-reliance.[13] Students are encouraged to actively explore the language,[14] and to develop their own 'inner criteria' as to what is linguistically acceptable. [15]

The role of the teacher is that of a coach. The teacher's task is to focus the students' attention, and provide exercises to help them develop language facility; however, to ensure their self-reliance, the teacher should only help the students as much as is strictly necessary.[16] For example, teachers will often give students time to correct their own mistakes before giving them the answer to a question.[17] Teachers also avoid praise or criticism, as it can discourage students from developing self-reliance.[17] As Gattegno says, "The teacher works with the student; the student works on the language."[18]

In the Silent Way students are seen as bringing experience and knowledge with them to the classroom. The teacher capitalizes on this knowledge when introducing new material, always building from the known to the unknown.[19] The students begin learning the language by work on its sound system. The sounds are associated with different colors on a sound-color chart that is specific to the language being learned. The teacher first elicits sounds that are already present in the students' native language, and then progresses to the development of sounds that are new to them. These sound-color associations are later used to help the students with spelling and reading.[18]

The Silent Way loosely follows a structural syllabus. The teacher will typically introduce one new language structure at a time, and old structures are continuously reviewed and recycled.[13] These structures are chosen for their propositional meaning, not for their communicative value.[20] The teacher will set up learning situations for the students which focus their attention on each new structure.[18] For example, the teacher might ask students to work with a floor plan of a house in order to introduce the concepts of inside and outside.[21] Once the language structures have been presented in this way, learners learn the grammar rules through a process of induction.[20]

Gattegno saw the choice of which vocabulary to teach as vital to the language learning process. He advised teachers to concentrate on the most functional and versatile words, many of which may not have direct equivalents in the learner’s native language.[20]

Translation and rote repetition are avoided, and instead emphasis is placed on conveying meaning through students' perceptions, and through practicing the language in meaningful contexts.[22] In the floor plan example, the plan itself removes the need for translation, and the teacher is able to give the students meaningful practice simply by pointing to different parts of the house.[21] The four skills of active listening, speaking, reading, and writing are worked on from the beginning stages, although students only learn to read something after they have learned to say it.[23]

Evaluation in the Silent Way is carried out primarily by observation. Teachers may never give a formal test, but they constantly assess students by observing their actions. This allows them to respond straight away to any problems the students might have.[24] Teachers also gain feedback through observing students' errors; errors are seen as natural and necessary for learning, and can be a useful guide as to what structures need more practice.[17] Furthermore, teachers may gain feedback by asking the students at the end of the lesson.[14] When evaluating the students, teachers expect them to learn at different rates, and students are not penalized for learning more slowly than their classmates. Teachers look for steady progress in the language, not perfection.[17]

Process

[edit]Teaching techniques

[edit]As the name implies, silence is a key tool of the teacher in the Silent Way. From the beginning levels, students do 90 percent or more of the talking.[25] Being silent moves the focus of the classroom from the teacher to the students,[26] and can encourage cooperation among them.[17] It also frees the teacher to observe the class.[14] Silence can be used to help students correct their own errors. Teachers can remain silent when a student makes a mistake to give them time to self-correct;[17] they can also help students with their pronunciation by mouthing words without vocalizing, and by using certain hand gestures.[27] When teachers do speak, they tend to say things only once so that students learn to focus their attention on them.[14]

A Silent Way classroom also makes extensive use of peer correction. Students are encouraged to help their classmates when they have trouble with any particular feature of the language. This help should be made in a cooperative fashion, not a competitive one. One of the teacher's tasks is to monitor these interactions so that they are helpful and do not interfere with students' learning.[28]

Teaching materials

[edit]

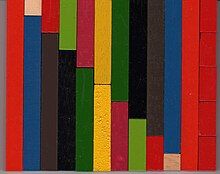

The silent way makes use of specialized teaching materials: colored Cuisenaire rods, the sound-color chart, word charts, and Fidel charts. The Cuisenaire rods are wooden or plastic, and come in ten different lengths, but identical cross-section; each length has its own assigned color.[25] The rods are used in a wide variety of situations in the classroom. At the beginning stages they can be used to introduce grammar. For example, to teach prepositions the teacher could create a situation for which the students use the statement "The blue rod is between the green one and the yellow one". They can also be used more abstractly, perhaps to represent a clock when students are learning about time.[29]

The sound-color chart consists of blocks of color, with one color representing one sound in the language being learned. The teacher uses this chart to help teach pronunciation; as well as pointing to colors to help students with the different sounds, the teacher can also tap particular colors harder to help students learn word stress. Later in the learning process, students can point to the chart themselves. The chart can help students to become aware of sounds that may not occur in their first language, and it also allows students to practice making these sounds without relying on mechanical repetition. It also provides an easily verifiable record of which sounds the students have and which they have not, which can help their autonomy.[28]

The word charts contain the functional vocabulary of the target language, and use the same color scheme as the sound-color chart. Each letter is colored in a way that indicates its pronunciation. The teacher can point to the chart to highlight the pronunciation of different words in sentences that the students are learning. There are twelve word charts in English, containing a total of around five hundred words.[30] The Fidel also use the same color-coding, and list the various ways that sounds can be spelled. For example, in English, the entry for the sound /ey/ contains the spellings ay, ea, ei, eigh, etc., all written in the same color. These can be used to help students associate sounds with their spelling.[31]

Reception and influence

[edit]As of 2000, the Silent Way was only used by a small number of teachers. These teachers often work in situations where accuracy is important. Their classes may also be challenging, for example working with illiterate refugees.[32] However, the ideas behind the Silent Way continue to be influential,[33] particularly in the area of teaching pronunciation.[34][35]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Gattegno 1963, available as Gattegno 1972.

- ^ Cook 2008, pp. 266–270.

- ^ Richards 1986, pp. 81–89.

- ^ Jin & Cortazzi 2011, pp. 568–569.

- ^ Gattegno, Caleb (1985). The Science of Education (Chapter 13). New York: Educational Solutions Inc. ISBN 0-87825-186-3. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ Gattegno, Caleb (1983). Oller, J; Richard-Amato, P (eds.). The Silent Way. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House. pp. 72–88. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ Young, Roslyn (2022). "The class conversation vs. the conversation class". Voices (286): 12–13.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Stevick 1974, p. 1.

- ^ a b Richards 1986, p. 81.

- ^ Gattegno 1972, p. 84, cited in Richards 1986, p. 82.

- ^ Stevick 1974, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Richards 1986, p. 83.

- ^ a b Larsen-Freeman 2000, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d Larsen-Freeman 2000, p. 63.

- ^ Larsen-Freeman 2000, p. 60.

- ^ Larsen-Freeman 2000, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b c d e f Larsen-Freeman 2000, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Larsen-Freeman 2000, p. 65.

- ^ Larsen-Freeman 2000, pp. 60, 63.

- ^ a b c Richards 1986, p. 82.

- ^ a b Larsen-Freeman 2000, p. 59.

- ^ Larsen-Freeman 2000, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Larsen-Freeman 2000, p. 66.

- ^ Larsen-Freeman 2000, pp. 60, 67.

- ^ a b Stevick 1974, p. 2.

- ^ Larsen-Freeman 2000, p. 61.

- ^ Larsen-Freeman 2000, pp. 62, 69.

- ^ a b Larsen-Freeman 2000, p. 68.

- ^ Larsen-Freeman 2000, p. 69.

- ^ Larsen-Freeman 2000, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Larsen-Freeman 2000, p. 70.

- ^ Byram 2000, p. 546-548.

- ^ Young & Messum 2013.

- ^ Underhill 2005.

- ^ Messum 2012.

References

[edit]- Byram, Michael, ed. (2000). Routledge Encyclopedia of Language Teaching and Learning. London: Routledge.

- Cook, Vivian (2008). Second Language Learning and Language Teaching. London: Arnold. ISBN 978-0-340-95876-6.

- Gattegno, Caleb (1963). Teaching Foreign Languages in Schools: The Silent Way (1st ed.). Reading, UK: Educational Explorers. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- Gattegno, Caleb (1972). Teaching Foreign Languages in Schools: The Silent Way (2nd ed.). New York: Educational Solutions. ISBN 978-0-87825-046-2. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- Jin, Lixian; Cortazzi, Martin (2011). "Re-Evaluating Traditional Approaches to Second Language Teaching and Learning". In Hinkel, Eli (ed.). Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning, Volume 2. New York: Routledge. pp. 558–575. ISBN 978-0-415-99872-7.

- Larsen-Freeman, Diane (2000). Techniques and Principles in Language Teaching. Teaching Techniques in English as a Second Language (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-435574-2.

- Messum, Piers (2012). "Teaching pronunciation without using imitation" (PDF). In Levis, J.; LeVelle, K. (eds.). Proceedings of the 3rd Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference. Ames, IA: Iowa State University. pp. 154–160. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- Raynal, Jean-Marc (1995). "La mise en place des premiers apprentissages des automatismes linguistiques avec la didactique du Silent Way". L'Enseignement du Français Au Japon. 23: 51–61. doi:10.24495/efj.23.0_51. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- Raynal, Jean-Marc (1997). "Pédagogie et langage à l'étude du cinéma". L'Enseignement du Français Au Japon. 25: 36–39. Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- Raynal, Jean-Marc (2011). "Language and Reality". Retrieved 2017-01-21.

- Richards, Jack (1986). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching: A Description and Analysis. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-32093-1.

- Stevick, Earl (1974). "Review of Teaching Foreign Languages in the Schools: The Silent Way" (PDF). TESOL Quarterly. 8 (3): 305–313. doi:10.2307/3586174. JSTOR 3586174. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

- Underhill, Adrian (2005). Sound Foundations. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1405064101.

- Young, Roslyn (2011). L'anglais avec l'approche Silent Way. Paris: Hachette. ISBN 978-2-212-54978-2.

- Young, Roslyn; Messum, Piers (May 2013). "Gattegno's legacy". Voices (232). IATEFL: 8–9. ISSN 1814-3830. Retrieved August 14, 2015.