Hobart and William Smith Colleges

| |

Former name | Geneva Academy (1794–1822) Geneva College (1822–1852) William Smith College for Women (1908) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Hobart: Disce William Smith: Βίος, ψυχή |

Motto in English | Hobart: Learn William Smith: Life, Soul |

| Type | Private liberal arts colleges |

| Established | Hobart: 1822 William Smith: 1908 |

Academic affiliations | Annapolis Group CLAC New York 6 AALAC |

| Endowment | $296 million (2021)[1] |

| President | Mark D. Gearan |

Academic staff | 214 (full-time)[2] |

| Undergraduates | 2,229[2] |

| Location | , U.S. 42°51′26″N 76°59′07″W / 42.857123°N 76.985407°W |

| Campus | Small town, 170 acres (69 ha) |

| Colors | Hobart: Orange & purple William Smith: Green & white |

| Nickname | Statesmen (Hobart) Herons (WS) |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division III, Liberty League, NEHC, MAISA |

| Website | www |

| |

Hobart and William Smith Colleges are private liberal arts colleges in Geneva, New York. They trace their origins to Geneva Academy established in 1797. Students can choose from 45 majors and 68 minors with degrees in Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science, Master of Arts in Teaching, Master of Science in Management, and Master of Arts in Higher Education Leadership.[3]

The colleges were originally separate institutions – Hobart College for men and William Smith College for women – that shared close bonds and a contiguous campus. Founded as Geneva College in 1822, Hobart College was renamed in honor of its founder John Henry Hobart, bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York in 1852. William Smith College was founded in 1908 by Geneva philanthropist and nurseryman William Smith. They are officially chartered as "Hobart and William Smith Colleges" and informally referred to as "HWS" or "the Colleges". Although united in one corporation with many shared resources and overlapping organizations, they have each retained their traditions.

Today, students are free to participate in each of the colleges' customs and traditions based on their preferred gender identities.[4] Students can graduate with diplomas issued by Hobart College, William Smith College, or Hobart and William Smith Colleges.

History

[edit]Hobart and William Smith Colleges, private colleges in Geneva, New York, began on the western frontier as the Geneva Academy. After some setbacks and disagreement among trustees, the academy suspended operations in 1817. By the time Bishop John Henry Hobart, of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, first visited the city of Geneva in 1818, the doors of Geneva Academy had just closed. Yet, Geneva was a bustling Upstate New York city on the main land and stage coach route to the West. Bishop Hobart had a plan to reopen the academy at a new location, raise a public subscription for the construction of a stone building, and elevate the school to college status. Roughly following this plan, Geneva Academy reopened as Geneva College in 1822 with conditional grant funds made available from Trinity Church in New York City. Geneva College was renamed Hobart College in 1852 in honor of its founder, Bishop Hobart.

William Smith College was founded in 1908, originally as William Smith College for Women. Its namesake and founder was a wealthy local nurseryman, benefactor of the arts and sciences, and philanthropist. The school arose from negotiations between William Smith, who sought to establish a women's college, and Hobart College President Langdon C. Stewardson, who sought to redirect Smith's philanthropy toward Hobart College. Smith, however, was intent on establishing a coordinated, nonsectarian women's college, which, when realized, coincidentally gave Hobart access to new facilities and professors. The two student bodies were educated separately in the early years, even though William Smith College was a department of Hobart College for organizational purposes until 1943. That year, after a gradual relaxation of academic separation, William Smith College was formally recognized as an independent college, co-equal with Hobart. Both colleges were reflected in a new, joint corporate identity.

Early history and growth

[edit]Geneva Academy

[edit]Geneva Academy was founded in 1796 when Geneva was just a small frontier settlement. It is believed to be the first school formed in Geneva.[5] The area was considered "the gateway to Genesee County" and was in the early stages of development from the wilderness.[6]

In 1809, the trustees of the academy appointed Rev. Andrew Wilson, formerly of the University of Glasgow in Scotland as head of the school.[5] He remained until 1812 when Ransom Hubell, a graduate of Union College, was made principal.[5]

Geneva College

[edit]The Regents granted the full charter on February 8, 1825, and at that time, Geneva Academy officially changed its name to Geneva College.[5] Rev. J. Adams was president of the college as of 1827.

The "English Course," as it was known, was a radical departure from long-established educational usage and represented the beginning of the college work pattern found today.[6]

Geneva Medical College

[edit]Geneva Medical College was founded on September 15, 1834, as a department of Geneva College. The medical school was founded by Edward Cutbush, who also served as the first dean of the school.[6]

Elizabeth Blackwell

[edit]

In an era when the prevailing conventional wisdom was no woman could withstand the intellectual and emotional rigors of medical education, Elizabeth Blackwell, (1821–1910) applied to and was rejected – or simply ignored – by 29 medical schools before being admitted in 1847 to the Medical Institution of Geneva College.[7]

The medical faculty, largely opposed to her admission but seemingly unwilling to take responsibility for the decision, decided to submit the matter to a vote of the students. The men of the college voted to admit her.[8]

Blackwell graduated two years later, on January 23, 1849, at the top of her class to become the first woman doctor in the Northern Hemisphere.[7] "The occasion marked the culmination of years of trial and disappointment for Miss Blackwell, and was a key event in the struggle for the emancipation of women in the nineteenth century in America."[7]

Blackwell went on to found the New York Infirmary for Women and Children and had a role in the creation of its medical college.[7] She then returned to her native England and helped found the National Health Society and taught at the first college of medicine for women to be established there.

Hobart College

[edit]The school was known as Geneva College until 1852, when it was renamed in memory of its most forceful advocate and founder, Bishop Hobart, to Hobart Free College. In 1860, the name was shortened to Hobart College.[6]

Hobart College of the 19th century was the first American institution of higher learning to establish a three-year "English Course" of study to educate young men destined for such practical occupations as "journalism, agriculture, merchandise, mechanism, and manufacturing", while at the same time maintaining a traditional four-year "classical course" for those intending to enter "the learned professions." It also was the first college in America to have a dean of the college.

Notable 19th-century alumni included Albert James Myer, Class of 1847, a military officer assigned to run the United States Weather Bureau at its inception, was a founding member of the International Meteorological Organization, and helped birth the U.S. Signal Corps, and for whom Fort Myer, Virginia, is named; General E. S. Bragg of the Class of 1848, colonel of the Sixth Wisconsin Regiment and a brigadier general in command of the Iron Brigade who served one term in Congress and later was ambassador to Mexico and consul general of the U.S. in Cuba; two other 1848 graduates, Clarence A. Seward[9] and Thomas M. Griffith, who were assistant secretary of state and builder of the first national railroad across the Mississippi River, respectively; and Charles J. Folger, Class of 1836, a United States Secretary of the Treasury in the 1880s.

Until the mid-20th century, Hobart was strongly affiliated with the Episcopal Church and produced many of its clergy. While this affiliation continues to the present, the last Episcopal clergyman to serve as President of Hobart (1956–1966) was Louis Melbourne Hirshson. Since then, the president of the colleges has been a layperson.

During World War II, Hobart College was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program which offered students a path to a Navy commission.[10]

William Smith College

[edit]Toward the end of the 19th century, Hobart College was on the brink of bankruptcy. It was through the presidency of Langdon Stewardson the college obtained a new donor, nurseryman William Smith. Smith had built the Smith Opera House in downtown Geneva and the Smith Observatory on his property when he became interested in founding a college for women, a plan he pursued to the point of breaking ground before realizing it was beyond his means. As publicized in The College Signal on October 7, 1903, "William Smith, a millionaire nurseryman, will found and endow a college for women at Geneva, N. Y., to be known as the William Smith College for Women The institution will be in the most beautiful section. One building is to cost $150,000. Mr. Smith maintains the Smith observatory there."[11] In 1903, Hobart College President Langdon C. Stewardson learned of Smith's interest and, for two years, attempted to convince him to make Hobart College the object of his philanthropy. With enrollments down and its resources strained, Hobart's future depended upon an infusion of new funds. Unable to convince Smith to provide direct assistance to Hobart, President Stewardson redirected the negotiations toward founding a coordinated institution for women, a plan that appealed to the philanthropist. On December 13, 1906, he formalized his intentions; two years later William Smith School for Women – a coordinated, nonsectarian women's college – enrolled its first class of 18 students. That charter class grew to 20 members before its graduation in 1912.

In addition, Smith's gift made possible the construction of the Smith Hall of Science, to be used by both colleges, and permitted the hiring, also in 1908, of three new faculty members who would teach in areas previously unavailable in the curriculum: biology, sociology, and psychology.

World War II

[edit]Between 1943 and 1945, Hobart College trained almost 1,000 men in the U.S. Navy's V-12 program, many of whom returned to complete their college educations when the post-World War II GI Bill swelled the enrollments of American colleges and universities. In 1948, three of those veterans – William F. Scandling, Harry W. Anderson, and W. P. Laughlin – took over the operation of the Hobart dining hall. Their fledgling business was expanded the next year to include William Smith College; after their graduation, in 1949, it grew to serve other colleges and universities across the country, eventually becoming Saga Corporation, a nationwide provider of institutional food services.

1970 Coercion charges

[edit]Students and faculty of Hobart and William Smith Colleges were active during the anti-war movements in the late 1960s and early 1970s. On April 30, 1970, a group of first-year students threw three Molotov cocktails through the windows of the Air Force ROTC office located on the first floor of Sherrill Hall. The incident was incited by "Tommy the Traveler" an agent provocateur who worked for the Ontario County Police Department and the FBI. No one was injured and no significant damage was done to Sherrill Hall. In July of that year, the colleges were officially indicted on coercion charges in a landmark case in the history of higher education in the United States. The incident marks the first time in U.S. history that a college has been charged with criminal activities relating to a campus disorder.[12] The colleges were acquitted of all charges.

2014 Title IX investigation

[edit]On May 1, 2014, the U.S. Department of Education released a list of 55 colleges being investigated for potential violations of federal law regarding sexual assault and harassment complaints.[13] The list included Hobart and William Smith Colleges.[14] A New York Times article published in July of the same year detailed a case in which a student reported a sexual assault by three college football players two weeks into her first year; within two weeks the college's investigation cleared the two men accused, despite medical evidence, a corroborating witness to one of the incidents and discrepancies in the alleged perpetrators' accounts of the evening. The story also alleged the members of the disciplinary panel that heard the case were uninformed about sexual assault and frequently changed the subject rather than hear the victim's account of events.[15] Following the report, the colleges unveiled new initiatives and policies, including revising their sexual violence policies, creating a rape hotline and forming an Office of Title IX Programs and Compliance.[16]

Campus

[edit]

Layout

[edit]

Hobart and William Smith Colleges' campus is situated on 170 acres (0.69 km2) in Geneva, New York, along the shore of Seneca Lake, the largest of the Finger Lakes. The campus is notable for the style of Jacobean Gothic architecture represented by many of its buildings, notably Coxe Hall, which houses the President's Office and other administrative departments. In contrast, the earliest buildings were built in the Federal style and the chapel is Neo-Gothic.

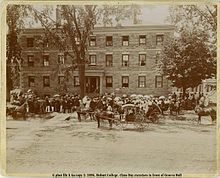

The Quad, the core of the Hobart campus, was formed by the construction of Medbery, Coxe, and Demarest. Several years later, Arthur Nash, a Hobart professor, designed Williams Hall, which would be constructed in the gap between Medbery and Coxe. The Quad is formed to the east by Trinity and Geneva Hall, the two original College buildings, and to the south by the Science compound, and Napier Hall. Geneva Hall (1822) and Trinity Hall (1837) were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[17] In 2016, the schools announced they were going solar by building two solar farms to create enough electricity for about 50 percent of HWS' needs.[18]

The Hill (or William Smith Hill) is a prominent feature of the historic William Smith campus. Located at the top of a large sloping hill to the West of Seneca Lake and the Hobart Quad, the Hill houses three historic William Smith dorms and one built in the 1960s (Comstock, Miller, Blackwell, and Hirshson Houses). At its peak resides William Smith's all-female dorms. The Hill was the site originally conceived for William Smith College. Unveiled in 2008 for the William Smith Centennial is a statue of the college's founder and benefactor, William Smith.

A fifteen-million-dollar expansion of the Scandling Campus Center was completed in the autumn of 2008. This renovation added over 17,000 additional square feet, including an expanded cafe, a new post office, and more meeting areas. In 2016 the Gearan Center for Performing Arts was completed for 28 million dollars, becoming the largest project in the history of the college.

Key buildings

[edit]Coxe Hall serves as the main administrative hub of the campus. Constructed in 1901, the building is named after Bishop Arthur Cleveland Coxe, a benefactor of the school, and houses the president's office, Bartlett Theater, The Pub, and a classroom wing, which was added in the 1920s. Arthur Cleveland Coxe was closely affiliated with the school. The building was designed by Clinton and Russell Architects.

Gearan Center for the Performing Arts, named in honor of President Mark D Gearan and Mary Herlihy Gearan, was in 2016. It includes a lobby that links three flexible performance and rehearsal spaces for theater, music, and dance. Also included are faculty offices, practice and recital rooms, and a film screening room.

Scandling Campus Center, named after William F. Scandling '49, renovated and expanded in 2009, houses Saga (the dining hall), the post office, offices of student activities, a cafe, and Vandervort room (a large event space).

Gulick Hall was built in 1951 as part of the post-war "mini-boom" that also included the construction of the Hobart "mini-quad" dormitories Durfee, Bartlett, and Hale (each named for a 19th-century Hobart College president). Gulick Hall originally housed the campus dining services and, later, the Office of the Registrar. Completely renovated in 1991, Gulick now houses both the Office of the Registrar and the Psychology department, which was moved from Smith Hall in 1991 before its renovation in 1992.

Stern Hall, named for the lead donor, Herbert J. Stern '58, was completed in 2004. It houses the departments of economics, political science, anthropology & sociology, environmental studies, and Asian languages and cultures.

Smith Hall, built in 1907, originally housed both the Biology and Psychology Departments. It is now home to the Dean's Offices of both colleges, along with the departmental offices of Writing and Rhetoric and the various modern language departments. Smith Hall was the first building constructed with funds from William Smith on the William Smith College campus, but it is also the first building that has always been shared by both colleges.

Williams Hall, completed in 1907, housed the first campus gymnasium and, after the construction of Bristol gymnasium, served several other uses as a campus post office, book store, IT services, and location of the Music Department.

Demarest Hall, connected to St. John's Chapel by St. Mark's Tower, houses the departments of Religious Studies and English and Comparative Literature as well as the Women's Studies Program. Also home to the Blackwell Room, named in honor of Elizabeth Blackwell (once used as a study area and library, the space is now used for classrooms in the absence of more planning for classroom space), Demarest was designed by Richard Upjohn's son, Richard M. Upjohn. (Upjohn's grandson, Hobart Upjohn would design several of the college's buildings as well). Demarest served as the college's library until the construction of the Warren Hunting Smith Library in the early 1970s. In the 1960s it was expanded to hold the college's growing number of volumes. Today, it also houses the Fisher Center for the Study of Gender and Justice, an intellectual center led by such scholar faculty as Dunbar Moodie (Sociology), Betty Bayer (Women's Studies), and Jodi Dean (Political Science).

Trinity Hall built in 1837, was the second of the colleges' buildings. Trinity Hall was designed by college president Benjamin Hale, who taught architecture. Trinity served as a dormitory and a library, but it was converted into a space for classrooms, labs, and offices later in the 19th century. It presently is home to the Salisbury Center for Career Services.

Merrit Hall, completed in 1879, was built on the ruins of the old medical college. Merrit was the first science building on campus and housed the chemistry labs. Merrit also housed a clock atop the quad side of the building. On the eve of the Hobart centennial in 1922, students climbed to the top and made the bell strike 100 times. Merrit Hall was also one of the first buildings shared by Hobart and William Smith. Today Merrit Hall houses a lecture hall and faculty offices. St. John's Chapel, designed by Richard Upjohn the architect of Trinity Church in New York City, served as the religious hub of the campus, replacing Polynomous, the original campus chapel. In the 1960s, St. John's was connected to Demarest Hall by St. Marks Tower.

Houghton House, the mansion, known for its Victorian elements, is home to the Art and Architecture departments. The country mansion was built, in the 1880s by William J. King. It was purchased in 1901 by the wife of Charles Vail (maiden name Helen Houghton), Hobart graduate and professor, as the family's summer home. Mrs. Vail remodeled the Victorian mansion's interior to the present classical decor in 1913. The family's "townhome" is 624 S. Main Street and is now the Sigma Phi fraternity. Helen Vail's heirs donated the house and its grounds to the colleges to be used as a women's dormitory. After many years as a student dorm, the house became home to the art department after the original art studio was razed to make way for the new Scandling Campus Center. The building is now home to the Davis Art Gallery, with lecture rooms, multiple faculty offices, and architecture studios on the top floor.

Katherine D. Elliot Hall, was constructed in 2006. The "Elliot" houses 14,600 square feet (1,360 m2) contain art classrooms; offices; studios for painting, photography, and printing; and wood and metal shops.

Goldstein Family Carriage House was built by William J. King in 1882 and was renovated in 2006 to house a digital imaging lab and a photo studio with a darkroom for black-and-white photography.

Warren Hunting Smith Library, in the center of the campus, houses 385,000 volumes, 12,000 periodicals, and more than 8,000 VHS and DVD videos. In 1997, the library underwent a major renovation, undergoing several improvements, such as the addition of multimedia centers, and the addition to its south side of the L. Thomas Melly Academic Center, a spacious, modern location for "round the clock" study.

Napier Hall, attached to the Rosenberg Hall, houses several classrooms and was completed in 1994.

Rosenberg Hall, named for Henry A. Rosenberg (Hobart '52), is an annex of Lansing and Eaton Hall, the original science buildings. Rosenberg houses many labs and offices.

Lansing Hall, built in 1954, is home to Sciences and Mathematics. The building is named after John Ernest Lansing, Professor of Chemistry (1905–1948), who twice served as acting president.

Eaton Hall, is named for Elon Howard Eaton, a Professor of Biology (1908–1935). Eaton, one of New York's outstanding ornithologists, was one of the professors brought to campus with William Smith grant funds. Eaton Hall is a part of the science complex at the south end of the Hobart Quad, which consists of Lansing, Rosenberg, and Napier.

Dormitories

[edit]

Men's dorms

[edit]- Geneva Hall, built in 1822, is the college's first building, and the cornerstone site designated by the School's founder, Bishop John Henry Hobart. The building is one of the oldest academic buildings in continuous use, having served as a dormitory, among other uses, since its completion. The building has inscribed into its quoins, and alongside the perimeter of its facade, plaques that list the graduates of classes dating back to the 19th century.

- The Mini Quad, consisting of three buildings, Durfee, Hale, and Bartlett, houses about 150 Hobart students. Since the 2006 academic year, the dorms have become coeducational, with at least one-floor housing William Smith Students.

- Hale Hall is named for Benjamin Hale, president of Hobart College from 1836 to 1858.

- Bartlett Hall was named after the Reverend Murray Bartlett, who served as the fourteenth president of Hobart College from 1919 to 1936

- Durfee Hall was named after William Pitt Durfee, who from 1884 to 1929 served as Professor of Mathematics and Chair of the Mathematics Department. He was the first dean of a liberal arts college and served as acting president of the college four times.

Women's dorms

[edit]- Blackwell House was designed and built in 1860 by Richard Upjohn as a residence for William Douglass, who served as a trustee of Hobart College. The house was purchased in 1908 as the first William Smith dormitory. The house still houses William Smith students and is known for its grand Victorian features from fireplaces to chandeliers, to large old windows. Though rarely recognized as such, the house is named for Elizabeth Blackwell, an early graduate of what became the colleges.

- Comstock House was designed by Richard Upjohn's grandson, Hobart Upjohn, in 1932. Comstock is a women's dormitory named for Anna Botsford Comstock, a friend of William Smith and the first woman to be named a member of the board of trustees.

- Miller House was William Smith College's second dormitory. Miller was designed by Arthur Nash, professor and grandson of Arthur Cleveland Coxe. Nash also designed Smith Hall and Williams Hall. This house honors Elizabeth Smith Miller, a leader in the women's movement.

- Hirshson House, completed in 1962, was named for the president of the colleges, Louis Melbourne Hirshson, the last Episcopal clergy person to serve in that capacity. The building is home to William Smith students.

Coed dorms

[edit]- Medbery Hall is an original Hobart College dorm dating from the 1900. Medbery defines the right side of the Hobart Quadrangle. Designed by Clinton and Russell architects at the same time as Coxe Hall, the two buildings share similarities in their Jacobean Gothic style. Medbery is adorned with a recognizable Flemish roofline. Medbery was designed without long hallways "conducive to rioting" and mischief, such as rolling a cannonball down the hallway. Such mischief was experienced in the other two dormitories on campus, Geneva and Trinity Halls.

- Jackson, Potter, Rees, together known as JPR for short (and once dubbed "superdorm"), the three identical buildings create their quad in the south end of campus. The dorms were built in 1966 and are named after various historical figures of Hobart College. The complex houses about 230 first-year and upper-class Hobart and William Smith students. The building was completely renovated in 2005 to include quad living spaces (two double bedrooms connected by a common living room) and open lounge spaces and lounges on every floor.

- Jackson Hall is named for Abner Jackson, president of the Hobart in the middle of the 19th century. Jackson would go on to become president of Trinity College in Connecticut, where he would be the principal designer of its present campus.

- Rees Hall is named for Major James Rees, an early settler and landowner in Geneva and an acquaintance of George Washington.

- Potter Hall is named for John Milton Potter, President of Hobart and William Smith Colleges from 1942 to 1947.

- The Village at Odell's Pond is a collection of apartment-style dorms available to upperclassmen at the colleges. The units have either four or five bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, a living room, and a kitchen.

- Emerson Hall was built in 1969. The rooms are designed as suites, with two doubles and two singles and a common living room and bathroom.

- Caird Hall was built, along with deCordova, in 2005. The dorm has provisions for singles, doubles, and quads, and is often desired by students due to the separate temperature controls in each room. The ground floor hosts a lounge area with both gaming and fitness equipment for students.

- deCordova Hall was built, along with Caird, in 2005. The dorm has provisions for singles, doubles, and quads, and separate temperature controls in each room. The ground floor has a lounge area for students, as well as the deCordova cafe. [19]

The surrounding ecosystem plays a major role in the colleges' curriculum and acquisitions. The colleges own the 108-acre (0.44 km2) Hanley Biological Field Station and Preserve on neighboring Cayuga Lake and hosts the Finger Lakes Institute, a non-profit institute focusing on education and ecological preservation for the Finger Lakes area.

On Seneca Lake, one will find the William Scandling, a Hobart and William Smith 65-foot (20 m) research vessel used to monitor lake conditions and in the conduct of student and faculty research.

The colleges also own and operate WEOS-FM and WHWS-LP, public radio stations broadcasting throughout the Finger Lakes and worldwide, on the web.

Academics

[edit]Hobart and William Smith Colleges offer the degrees of Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science, and Master of Arts in Teaching. The colleges follow the semester calendar, have a student-to-faculty ratio of 10:1, and average class size of 16. Hobart and William Smith Colleges was accredited by the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools[20] until 2023. It is now accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education.[21] Its most popular majors, by 2021 graduates, were:[22] Economics (82), Mass Communication/Media Studies (42), Psychology (41), Biology/Biological Sciences (34), History (31) and Political Science & Government (30).

Curriculum

[edit]The curriculum was last reviewed and revised in the 2014–15 academic year.[23] Voted on by the faculty, the curriculum adopted the animating principle: Explore. Collaborate. Act. The revisions also adopted a Writing Enriched Curriculum model, the implementation of capstone experiences across all programs and departments, and enhanced the First Year Experience.[24] Specifically, to graduate from Hobart and William Smith Colleges, students must:

- Pass 32 academic courses, including a First-Year Seminar

- Complete the requirements for an academic major, including a capstone course or experience, and an academic minor (or second major). Students cannot major and minor in the same subject.

- Complete a course of study, designed in consultation with a faculty adviser, which addresses each of the eight educational goals:

- Critical Thinking

- Communication

- Quantitative Reasoning

- Scientific Inquiry

- Artistic Process

- Social Inequalities

- Cultural Difference

- Ethical Judgment

First-Year Seminar

[edit]First-Year Seminars are discussion-centered, interdisciplinary and collaborative. The only required course at HWS, seminar classes are small – usually about 15 students. They are intended to help students:

- Develop critical thinking and communication skills

- Understand the colleges’ intellectual and ethical values

- Establish a strong network of relationships with peers and mentors

Seminar topics vary each year, as do the professors who teach them. Many First-Year Seminars are linked to a learning community. Students enrolled in a learning community take one or more courses together. They also live together on the same floor of a co-ed residence hall and attend some of the same lectures and field trips.[25]

Global education

[edit]More than 60% of Hobart and William Smith students participate in off-campus study before they graduate.[26] The colleges offer study abroad sites on 6 continents with courses available in many academic disciplines.[27] Admission to these programs is competitive.

In the 2020 edition of The Princeton Review's Best 385 Colleges, Hobart and William Smith Colleges' study abroad program was ranked third on the "Most Popular Study Abroad" list,[28] marking four years in a row that HWS was a top-10 study abroad school (No. 7 in 2017 and No. 1 in the 2018 and 2019 editions).

President Joyce P. Jacobsen

[edit]On July 1, 2019, Joyce P. Jacobsen began serving as the 29th President of Hobart College and the 18th of William Smith College. She is the first woman to serve as president of Hobart and William Smith Colleges.[29] She resigned as President effective July 2022, and continues to teach at the colleges.

Rankings

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| Liberal arts | |

| U.S. News & World Report[30] | 70 |

| Washington Monthly[31] | 46 |

| National | |

| Forbes[32] | 190 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[33] | 143 |

In its 2024 edition, U.S. News & World Report ranks Hobart and William Smith Colleges as tied for 70th best liberal arts college in the U.S. and 81st in "Best Value Schools".[34]

In 2019, Forbes rated it 190th overall in "America's Top Colleges," which ranked 650 national universities, liberal arts colleges, and service academies.

Trias Writers-in-Residence

[edit]Founded in 2011 with a grant from alumnus Peter Trias, Hobart and William Smith Colleges established the Trias Writer-in-Residence, which brings renowned authors to campus for a year to mentor undergraduate creative writing students. Former writers in residence have included Mary Ruefle, Mary Gaitskill, Tom Piazza, Chris Abani, and John D'Agata.

Elizabeth Blackwell Award

[edit]In honor of Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910), the first woman in America to receive a Doctor of Medicine degree, the Elizabeth Blackwell Award is given by Hobart and William Smith Colleges to a woman whose life exemplifies outstanding service to humanity. Its recipients have included Chair of the Federal Reserve Janet Yellen (2015); the Most Rev. Katharine Jefferts Schori (2013); Eunice Kennedy Shriver (2011); first woman ordained a rabbi in the United States, Rabbi Sally Priesand (2009); Wangari Maathai (2008), first African woman to receive the Nobel Prize; the first woman to be ordained to the episcopate in the worldwide Anglican Communion, Bishop Barbara Harris (2004); Secretary of State Madeleine Albright (2001); tennis great Billie Jean King (1998); Wilma Mankiller (1996), first woman chief of the Cherokee Nation; U.S. Representative Barbara Jordan (1993); U.S. Senator Margaret Chase Smith (1991); former Surgeon General Antonia Novello (1991); Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor (1985); Fe del Mundo, the first Asian woman admitted to Harvard Medical School (1966); Miki Sawada, who started an orphanage for abandoned mixed-race children (1960); among many others.[35]

President's Forum

[edit]Each semester, Hobart and William Smith sponsors a series of guest lectures. The most prominent has been the President's Forum, established in 2000 and led by former president Mark Gearan. The forum has included The Hon. Shireen Avis Fisher, Nancy Zimpher, Mary Matalin and James Carville, Kathy Platoni, Svante Myrick, Cornel West, Ralph Nader, Hillary Clinton, Eric Liu, and Alan Keyes, among other prominent names.

Publications

[edit]Seneca Review, founded in 1970 by James Crenner and Ira Sadoff, is published twice yearly, spring and fall, by Hobart and William Smith Colleges Press. Distributed internationally, the magazine's emphasis is poetry, and the editors have a special interest in translations of contemporary poetry from around the world. Publisher of numerous laureates and award-winning poets, including Seamus Heaney, Rita Dove, Jorie Graham, Yusef Komunyakaa, Lisel Mueller, Wislawa Szymborska, Charles Simic, W.S. Merwin, and Eavan Boland, Seneca Review also consistently publishes emerging writers. In 1997, Seneca Review began publishing the "lyric essay," creative nonfiction that borders on poetry, under the associate editorship of John D'Agata.

Echo and Pine is the annual student-produced college yearbook. Originally two separate publications, the Hobart Echo of Seneca, and the William Smith Pine, the two merged in the 1960s to create one publication to serve both colleges. The Herald is the student-run school newspaper, founded in the late 19th century as the Hobart Herald. The Pulteney St. Survey is the official magazine of Hobart and William Smith Colleges. martini is the alternative student publication at Hobart & William Smith Colleges featuring an oftentimes witty and critical look at music, politics, and social issues on both the colleges' campus and on the national level.

Thel provides an outlet for HWS student artists and writers. The bi-annual, student-run publication features poetry, photography, visual art, and short stories created by HWS students. The Aleph is a journal that expresses global perspectives by conveying the insights of HWS and Union College students who studied abroad in joint programs as well as international and exchange students from both campuses. The journal is sponsored by the Hobart and William Smith Colleges and Union College Partnership for Global Education.

Debate

[edit]The HWS Debate Team dates back over 100 years. Notable recent victories include the 2016 Cornell IV, the 2015 Brad Smith Debate Tournament @ University of Rochester, the 2012 US National Championships, and the 2012 and 2009 Northeastern Regional Championship. The team hosts the HWS IV (one of the largest tournaments in North America) each fall, and the HWS Round Robin (an international tournament of champions) each spring. Every year, an HWS debater is honored with the Nathan D. Lapham Prize in Public Speaking, which comes with a cash award of up to $1000 to the student. HWS is among the few liberal arts colleges to offer numerous four-year debate scholarships.

Music

[edit]Hobart and William Smith has several ensemble groups,[36] including:

- Colleges Chorale, a mixed ensemble that performs a wide range of a cappella choral repertoire — music from the Middle Ages to the present. In addition to a formal concert at the end of each semester and the annual spring tour, the Colleges Chorale performs at various campus events throughout the year.

- Cantori is a chamber vocal ensemble comprising members from the larger Colleges Chorale. Since the group's formation in 1993, the sixteen-member Cantori has sought to foster contemporary choral music through the Cantori Commissioning Project – the annual commissioning and performance of a new work by a deserving American composer.

- Classical Guitar Ensemble - a student group providing a performance opportunity for talented student guitarists.

- Community Chorus - students, faculty, and staff at the colleges, and members from the surrounding community. The fifty-voice ensemble performs major works from the standard repertoire as well as lesser-known works deserving wider familiarity. Recent programs have included extended works by Franz Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Franz Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn, Gabriel Fauré, Ottorino Respighi, Sir Edward Elgar, Aaron Copland, Benjamin Britten, and Randall Thompson.

- Community Wind Ensemble - students, faculty, and staff at the colleges and members from the surrounding community. This relatively new ensemble looks forward to exploring the rich and diverse repertoire composed for wind ensemble.

- Jazz Ensemble - a student group providing a performance opportunity for talented student jazzers. Arrangements are found to accommodate a variety of instrumental combinations.

- Jazz Guitar Ensemble - a student group providing a performance opportunity for talented student jazz guitarists.

- Percussion Ensemble - a student group providing a performance opportunity for talented student percussionists, although students with minimal experience are encouraged to audition.

- String Ensemble - a student chamber group providing a performance opportunity for talented string players.

- Hobartones - Hobart College's student-run all-male a cappella group.

- Three Miles Lost - William Smith College's student-run all-female a cappella group

- Perfect Third - HWS's student-run, coed a cappella group.

Athletics

[edit]Varsity sports

[edit]There are 30 varsity sports at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, with about 43% of students involved at the varsity level. Hobart sponsors 15 varsity programs (alpine skiing, baseball, basketball, cross country, football, golf, ice hockey, lacrosse, swimming & diving, rowing, sailing, soccer, squash, tennis, volleyball), while William Smith also sponsors 15 varsity programs (alpine skiing, basketball, bowling, cross country, field hockey, golf, ice hockey, lacrosse, rowing, sailing, soccer, squash, swimming & diving, tennis, volleyball). Hobart and William Smith varsity teams have won 24 national championships and 124 conference championships, producing 675 All-Americans and 43 Academic All-America honorees.[37][38][39] In March 2017, Hobart and William Smith were named to the "100 Best Colleges for Sports Lovers" by Money and Sports Illustrated.[40]

- Affiliations

The colleges compete in NCAA Division III, except men's lacrosse, which competes in the Division I Atlantic 10 Conference (A-10). The colleges' main conference affiliation is with the Liberty League with the following exceptions: Hobart ice hockey competes in the New England Hockey Conference; Hobart lacrosse competes in the A-10; and William Smith ice hockey competes in the United Collegiate Hockey Conference.

- Facilities

Hobart and William Smith recently finished construction on the Caird Center for Sports and Recreation, which is now home to most of its athletics teams.

- Football

Offensive linesman Ali Marpet, drafted in the second round, 61st overall, of the 2015 NFL draft, is the highest-drafted pick in the history of Division III football.[41] He was three-time All-Liberty League first team (2012, 2013, 2014), and 2014 Liberty League Co-Offensive Player of the Year—the first offensive lineman in league history to be so honored.[42][43][44]

- Field hockey

The William Smith field hockey team has captured three national championships, ascending to the top of Division III in 1992, 1997, and 2000.

- Lacrosse

The Statesmen lacrosse team has compiled fifteen national championships (1 USILA, 2 NCAA Division II, and 13 NCAA Division III).

- Sailing

The lone coed team, the HWS sailing team is a member of the Middle Atlantic Intercollegiate Sailing Association. In 2005, the colleges won the Inter-Collegiate Sailing Association Team Race National Championship and the ICSA Coed Dinghy National Championship.

- Soccer

The William Smith soccer team was the first Heron squad to capture a national championship, winning the 1988 title bout with a 1–0 victory over University of California, San Diego.[45][46] William Smith won its second national championship in 2013, defeating Trinity University.

- Crew

The Hobart Crew team has also found success, earning gold medals at the Head of The Charles Regatta, the ECAC National Invitational Regatta (most recently a gold in the 2nd varsity 8+ over the "Hometown Boys" of WPI in 2015), and the IRA National Championships. While the Hobart Crew team has won gold in every event they have entered since the inception of rowing as a Liberty League Sport, they failed to win the team championships only once (2004.) The eventual champions, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, were known for having a large team and were only able to defeat the Statesmen by securing a win in the 2nd Varsity 8+ – the only event that Hobart did not have an entry. However, over the past few seasons, Hobart has fielded one of the most dominant 2nd Varsity 8's in school history. The Crew Team took part in the Henley Royal Regatta in Henley, England in the summer of 1986, 1993, 1994, 2011, and most recently in the summer of 2015.[47] [48]

- Ice Hockey

The Hobart hockey team won its first national championship in 2023, defeating Adrian College 3-2 in overtime. Hobart repeated as national champion the following year with a win over Trinity College 2-0.

Mascot

[edit]Originally known as the Hobart Deacons, Hobart's athletic teams became known as the "Statesmen" in 1936, following the football team's season opener against Amherst College. The morning after the game, The New York Times referred to the team as "the statesmen from Geneva," and the name stuck. The nickname for William Smith's athletic teams comes from a contest held in 1982. Several names were submitted, but "Herons" was selected because of the strong and graceful birds that lived at nearby Odell's Pond. These elegant birds frequently flew over the athletic fields as the teams were practicing.

Rivalries

[edit]Hobart's archrival in football is Union College. Other team rivalries include Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (football, basketball); University of Rochester (football); Elmira College and Manhattanville College (hockey); Cornell University (one of the oldest in lacrosse) and St. John Fisher University, Syracuse University and Georgetown University (lacrosse); and University of Michigan (crew). William Smith has rivalries with St. Lawrence University (lacrosse, basketball, field hockey, squash), Union College (soccer, field hockey, basketball, lacrosse), Hamilton College (field hockey, basketball, and lacrosse) and Ithaca College (crew).

Notable alumni

[edit]Notable faculty

[edit]

- Benjamin Fish Austin (1850–1933), campaigner for women's education and proponent of the Spiritualism movement

- William Robert Brooks (1844–1922), astronomer who specialized in comet discovery and has some periodic comets named for him

- Ithiel de Sola Pool, social scientist and one of the leaders of the Simulmatics Corporation

- Elon Howard Eaton, founder of the biology department, state ornithologist, and author of bird books

- William A. Eddy, President of Hobart College, 1942

- Mark Gearan, President of Colleges, former White House Deputy Communications Director for President Bill Clinton, and former Director of the Peace Corps

- Andrew Harvey, Professor of English and author on religion and mysticism

- Susan Henking, president of Shimer College, professor emerita, formerly professor of religious studies, women's studies, and LGBT studies

- Matthew Kadane, Assistant Professor of History, main songwriter (along with brother Bubba) of Bedhead and The New Year

- Daniel A. McGowan, professor emeritus

- H. Wesley Perkins, Professor of Sociology and author of Father of Social Norms Marketing

- William Stevens Perry (1832–1898), history professor and president at Hobart College, author, and second bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Iowa

- Judith Graham Pool, discoverer of cryoprecipitate, a process for creating concentrated blood clotting factors which significantly improved the quality of life for hemophiliacs around the world

- Lyman Pierson Powell, former president of Hobart College, author, lecturer and priest

- Winifred Reuning (1953–2015), editor of the Antarctic Journal of the United States and namesake of the Reuning Glacier in Antarctica

- Janet Seeley (1905–1987), head of the physical education department who taught dance and choreographed dance programs

References

[edit]- ^ As of June 23, 2021. "Office of the President Statement". Hobart and William Smith Colleges. June 23, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "About HWS". Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ "Majors and Minors – Hobart and William Smith Colleges". www2.hws.edu. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "HWS to Offer Three Degree Options". Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "History of Ontario County – History of Geneva College in Geneva, New York". D. Mason & Company, Syracuse, N.Y., 1893. Retrieved June 6, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d "Hobart College, 125 Years Old, Prospers on Unusual". Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. June 1, 1947.

- ^ a b c d "Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell's Graduation – An Eyewitness Account by Margaret Munro De Lancey" (PDF). Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 12, 2003. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ^ "Changing the Face of Medicine – Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell". National Library of Medicine. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ^ "A Brief History of Clarence A. Seward". www.samueleells.org. The Samuel Eells Literary and Educational Foundation. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ^ The College Signal (Semi-monthly published by the Students of the Massachusetts Agricultural College) Vol. XIV. October 7, 1903. p. 21.

- ^ "The Pulteney St. Survey". www.hws.edu. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Department of Education Releases List of Higher Education Institutions with Open Title IX Sexual Violence Investigations". U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Department of Education Releases List of Higher Education Institutions with Open Title IX Sexual Violence Investigations". U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ Bogdanich, Walter (July 12, 2014). "Reporting Rape and Wishing She Hadn't: How One College Handled a Sexual Assault Complaint". The New York Times. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ Miller, Jim (August 31, 2014). "New initiatives, policies greet HWS students". Finger Lakes Times. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Hobart and William Smith Colleges go solar". Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- ^ "DeCordova, Emerson, and Caird Halls". Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ "Hobart & William Smith Colleges". Middle States Commission on Higher Education. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ "Hobart and William Smith Colleges". New England Commission Higher Education. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ "Hobart William Smith Colleges". nces.ed.gov. U.S. Dept of Education. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "HWS: Curriculum". Hws.edu. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Curriculum revision" (PDF). www.hws.edu. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "HWS: Academics - Course Catalogue". Hws.edu. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Hws: Irp". Hws.edu. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Programs > HWS Destinations > Center for Global Education". Global.hws.edu. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Best Colleges for Study Abroad Programs". The Princeton Review. Archived from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Hobart and William Smith Colleges - Dr. Joyce P. Jacobsen Named President of HWS". .hws.edu. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "2024-2025 National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "Hobart and William Smith Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. 2024.

- ^ "Elizabeth Blackwell Award Recipients". Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ "HWS Music Department". Hws.edu. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "National Champions". hwsathletics.com. SIDEARM Sports. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "Conference Champions". hwsathletics.com. SIDEARM Sports. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "Academic Champions". hwsathletics.com. SIDEARM Sports. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "100 Best Colleges for Sports Lovers". Money.com and Sports Illustrated. Money.com. March 9, 2017. Archived from the original on May 27, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ Kevin McGuire (May 2, 2015). "Ali Marpet puts D3 Hobart on the NFL Draft scoreboard – College Football Talk". NBC Sports.

- ^ "Liberty League Athletics – Liberty League announces 2014 Football Award Recipients". Liberty League.

- ^ "Press Release: News: Senior Bowl". seniorbowl.com.

- ^ "AFCA Announces 2014 Division III Coaches All-America Team". afca.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2015.

- ^ Marks, John (August 16, 2019). "William Smith College Athletics, 1972 – Present" (blog post). Geneva Historical Society. Retrieved November 9, 2019. "In 1988, soccer was the first team to win a national title. Field hockey followed with national championships in 1992, 1997, and 2000. Soccer won a second title in 2013."

- ^ Hazeltine, Rick (November 14, 1988). "UCSD Uses a Familiar Pair to Beat Emory in Soccer, 4-1". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 9, 2019. "The UCSD women’s team lost, 1-0, in sudden death to host William-Smith College of New York in the Division III final Sunday."

- ^ "Hobart Rowing Awards & History". hwsathletics.com/.

- ^ "Henley Thursday: Making the Most of Chances". row2k.com.

External links

[edit] Media related to Hobart and William Smith Colleges at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hobart and William Smith Colleges at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- HWS Athletics website

- Hobart and William Smith Colleges

- 1822 establishments in New York (state)

- Education in Ontario County, New York

- Educational institutions established in 1822

- Geneva, New York

- Liberal arts colleges in New York (state)

- Tourist attractions in Ontario County, New York

- U.S. Route 20

- Universities and colleges affiliated with the Episcopal Church (United States)

- Private universities and colleges in New York (state)