In His Own Write

First edition | |

| Author | John Lennon |

|---|---|

| Genre | |

| Published | 23 March 1964 by Jonathan Cape |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 80 |

| ISBN | 0-684-86807-5 |

| Followed by | A Spaniard in the Works |

In His Own Write is a 1964 nonsense book by the English musician John Lennon. Lennon's first book, it consists of poems and short stories ranging from eight lines to three pages, as well as illustrations.

After Lennon showed journalist Michael Braun some of his writings and drawings, Braun in turn showed them to Tom Maschler of publisher Jonathan Cape, who signed Lennon in January 1964. He wrote most of the content expressly for the book, though some stories and poems had been published years earlier in the Liverpool music publication Mersey Beat. Lennon's writing style is informed by his interest in English writer Lewis Carroll, while humorists Spike Milligan and "Professor" Stanley Unwin inspired his sense of humour. His illustrations imitate the style of cartoonist James Thurber. Many of the book's pieces consist of private meanings and in-jokes, while also referencing Lennon's interest in physical abnormalities and expressing his anti-authority sentiments.

The book was both a critical and commercial success, selling around 300,000 copies in Britain. Reviewers praised it for its imaginative use of wordplay and favourably compared it to the later works of James Joyce, though Lennon was unfamiliar with him. Later commentators have discussed the book's prose in relation to Lennon's songwriting, both in how it differed from his contemporary writing and in how it anticipates his later work, heard in songs like "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" and "I Am the Walrus". Released amidst Beatlemania, its publication reinforced perceptions of Lennon as "the smart one" of the Beatles, and helped to further legitimise the place of pop musicians in society.

Since its release, the book has been translated into several languages. In 1965, Lennon released another book of nonsense literature, A Spaniard in the Works. He abandoned plans for a third collection and did not publish any other books in his lifetime. Victor Spinetti and Adrienne Kennedy adapted his two books into a one-act play, The Lennon Play: In His Own Write, produced by the National Theatre Company and first performed in June 1968 to mixed reviews.

Background

[edit]Earliest influences

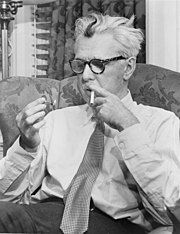

[edit]Right: The American cartoonist James Thurber, whose cartoons Lennon began imitating when he was a teenager

John Lennon was artistic as a child, though unfocused on his schooling.[1] He was mostly raised by his aunt Mimi Smith, an avid reader who helped shape the literary inclinations of both Lennon and his step-siblings.[2][3] Answering a questionnaire in 1965 about which books made the largest impression on him before the age of eleven, he identified Lewis Carroll's nonsense works Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, as well as Kenneth Grahame's children's book The Wind in the Willows.[4] He added: "These books made a great impact and their influence will last for the rest of my life".[5][note 1] He reread Carroll's books at least once a year,[8][9] being intrigued by the use of wordplay in pieces like "Jabberwocky".[10] His childhood friend Pete Shotton remembered Lennon reciting the poem "at least a few hundred times", and that, "from a very early age, John's ultimate ambition was to one day 'write an Alice' himself".[11] Lennon's first ever poem, "The Land of the Lunapots", was a fourteen-line piece written in the style of "Jabberwocky",[12] using Carrollian words like "wyrtle" and "graftiens".[13][note 2] Where Carroll's poem opens "'Twas brillig, and the ...",[17] Lennon's begins:[14]

T'was custard time and as I

Snuffed at the haggie pie pie

The noodles ran about my plunk

Which rode my wrytle uncle drunk

...

From around the age of eight, Lennon spent much of his time drawing, inspired by cartoonist Ronald Searle's work in the St Trinian's School cartoon strips.[4] He later enjoyed the illustrations of cartoonist James Thurber and began imitating his style around the age of fifteen.[18] Uninterested in fine art and unable to create realistic likenesses, he enjoyed doodling and drawing witty cartoons,[19] usually made with either a black pen or a fountain pen with black ink.[18] Filling his school notebooks with vignettes, poetry and cartoons,[20] he drew inspiration from British humorists such as Spike Milligan and "Professor" Stanley Unwin,[1] including Milligan's radio comedy programme The Goon Show.[21][22] He admired the programme's unique humour, characterised by attacks on establishment figures, surreal humour and punning wordplay, later writing that it was "the only proof that the WORLD was insane".[23] Lennon collected his work in a school exercise book dubbed the Daily Howl,[24] later described by Lennon's bandmate George Harrison as "jokes and avant-garde poetry".[18] Made in the style of a newspaper, its cartoons and ads featured wordplay and gags,[24] such as a column reporting: "Our late editor is dead, he died of death, which killed him".[25]

Despite Lennon's love of literature, he was a chronic misspeller, saying in a 1968 interview that he "never got the idea of spelling",[5] finding it less important than conveying an idea or story.[26] Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn raises the possibility that Lennon had dyslexia – a condition that often went undiagnosed in the 1940s and 1950s – but counters that he exhibited no other related symptoms.[27] Lennon's mother, Julia Lennon, similarly wrote with uncertain spelling and displayed weak grammar in her writing.[28] American professor James Sauceda contends that Unwin's use of fractured English was the foremost influence on Lennon's writing style,[29] and in a 1980 interview with Playboy, Lennon stated that the main influences on his writing "were always Lewis Carroll and The Goon Show, a combination of that".[30]

Art college and Bill Harry

[edit]Although most teachers at Quarry Bank High School for Boys were annoyed at Lennon's lack of focus, he impressed his English master, Philip Burnett, who suggested he go to art school at the Liverpool College of Art.[31] In 2006, Burnett's wife, June Harry, recalled of Lennon's cartoons: "I was intrigued by what I saw. They weren't academic drawings but hilarious and quite disturbing cartoons."[32] She continued: "Phil enjoyed John's slant on life. He told me, 'He's a bit of a one-off. He's bright enough, but not much apart from music and doing his cartoons interests him.'"[32] Having failed his GCE "O" levels, Lennon was admitted into the Liverpool College of Art solely on the basis of his art portfolio.[33] While attending the school he befriended fellow student Bill Harry in 1957.[34] When Harry heard that Lennon wrote poetry he asked to see some, later recalling: "He was embarrassed at first ... I got the impression that he felt that writing poetry was a bit effeminate because he had this tough macho image".[33] After further pressing, Lennon relented and showed Harry a poem, who remembered it as "a rustic poem, it was pure British humour and comedy, and I loved it".[33] Harry retrospectively stated that Lennon's writing style, especially his use of malapropisms, reminded him of Unwin.[35] Harry described his poetry as displaying an "originality in its sheer lunacy", but found his sense of humour "absurdly cruel with its obsession with cripples, spastics and torture".[36]

After Harry started the Liverpool newspaper Mersey Beat in 1961, Lennon made occasional contributions.[37] His column "Beatcomber", a reference to the "Beachcomber" column of the Daily Express,[37][38] included poems and short stories.[39][note 3] He typed his early pieces with an Imperial Good Companion Model T typewriter.[41] By August 1962, his original typewriter was either broken or unavailable to him. He borrowed an acquaintance's, spurring him to write more prose and poetry.[42] He enjoyed typewriters,[42] but found that his slow typing left him unmotivated to write for long periods of time and so he focused on shorter pieces.[18] He left keystroke errors uncorrected to add further wordplay.[43] Excited about being in print, he brought 250 pieces to Harry, telling him he could publish whatever he wanted of them.[39] Only two stories were published, "Small Sam" and "On Safairy with Whide Hunter", because Harry's fiancée Virginia accidentally threw out the other 248 during a move between offices.[44][note 4] Harry later recalled that after telling him about the accident, Lennon broke down in tears.[47]

Paul McCartney

[edit]Lennon's friend and bandmate Paul McCartney also enjoyed Alice in Wonderland, The Goon Show and the works of Thurber, and the two soon bonded through their mutual interests and similar senses of humour.[48] Lennon impressed McCartney, who did not know anyone else that either owned a typewriter or wrote their own poetry. He found hilarious one of Lennon's earliest poems, "The Tale of Hermit Fred", especially its final lines:[43]

I peel the bagpipes for my wife

And cut all negroes' hair

As breathing is my very life

And stop I do not dare.

Visiting Lennon's 251 Menlove Avenue home one day in July 1958, McCartney found him writing a poem and enjoyed the wordplay of lines like "a cup of teeth" and "in the early owls of the morecombe". Lennon let him help, with the two co-writing the poem "On Safairy with Whide Hunter", its title's origin likely the adventure serial White Hunter. Lewisohn suggests the renaming of the lead character at each appearance was probably Lennon's contribution, while lines that were likely McCartney's include: "Could be the Flying Docker on a case" and "No! But mable next week it will be my turn to beat the bus now standing at platforbe nine". He also suggests the character Jumble Jim was a reference to McCartney's father Jim McCartney.[49] Lennon typically wrote his pieces by hand at home and would bring them when he and his band, the Beatles, were travelling in a car or van to a gig. Reading the pieces aloud, McCartney and Harrison would often make contributions of their own. Upon returning home, Lennon would type up the pieces, adding what he could remember of his friend's contributions.[42]

Publication and content

[edit]

In 1963, Tom Maschler, the literary director of Jonathan Cape, commissioned American journalist Michael Braun to write a book about the Beatles.[50] Braun began following the band during their Autumn 1963 UK Tour in preparation for his 1964 book Love Me Do: The Beatles' Progress.[51] Lennon showed Braun some of his writings and drawings, and Braun in turn showed them to Maschler, who recalled: "I thought they were wonderful and asked him who wrote them. When he told me John Lennon, I was immensely excited."[50] At Braun's insistence, Maschler joined him and the band at Wimbledon Palais in London on 14 December 1963.[50] Lennon showed Maschler more of his drawings, mainly doodles made on scrap pieces of paper[52] that had mostly been done in July 1963 while the Beatles played a residency in Margate.[53] Maschler encouraged him to continue with his pieces and drawings, then selected the title In His Own Write from a list of around twenty prospects,[52] the pick originally an idea of McCartney.[54][55] Among the rejected titles were In His Own Write and Draw,[54] The Transistor Negro, Left Hand Left Hand and Stop One and Buy Me.[52][note 5]

Lennon signed a contract with Jonathan Cape for the book on 6 January 1964, receiving an advance of £1,000 (equivalent to £26,000 in 2023).[52] He contributed 26 drawings and 31 pieces of writing, including 23 prose pieces and eight poems,[57] bringing the book's length to 80 pages.[52] Its pieces range in length from the eight-line poems "Good Dog Nigel" and "The Moldy Moldy Man" to the three-page story "Scene three Act one".[58] Lennon reported that his work on the book's illustrations was the most drawing he had done since leaving art school.[18] Most of the written content was new,[18] but some had been done previously, including the stories "On Safairy with Whide Hunter" (1958), "Henry and Harry" (1959), "Liddypool" (1961 as "Around And About"), "No Flies on Frank" (1962) and "Randolf's Party" (1962), and the poem "I Remember Arnold" (1958),[59] which he wrote following the death of his mother, Julia.[60] Lennon worked spontaneously and generally did not return to pieces after writing them, though he did revise "On Safairy with Whide Hunter" in mid-July 1962, adding a reference to the song "The Lion Sleeps Tonight", a hit in early 1962.[61][note 6] Among the book's literary references are "I Wandered", which includes several plays on the title of the poem "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" by English poet William Wordsworth;[65] "Treasure Ivan", which is a variation on the plot of Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson;[66] and "At the Denis", which paraphrases a scene at a dentist's office from Carlo Barone's English-teaching book, A Manual of Conversation English-Italian.[67][68]

It's about nothing. If you like it, you like it; if you don't, you don't. That's all there is to it. There's nothing deep in it, it's just meant to be funny. I put things down on sheets of paper and stuff them in my pocket. When I have enough, I have a book.[18]

In His Own Write was published in the UK on 23 March 1964,[52] retailing for 9s 6d (equivalent to £12 in 2023).[69][70] Lennon attended a launch party at Jonathan Cape's London offices the day before.[71] Maschler refused a request from his superiors at Jonathan Cape that the cover depict Lennon holding a guitar, instead opting for a simple head shot.[72] Photographer Robert Freeman designed the first edition of the book,[73] a black-and-white photograph he took of Lennon also adorning the cover.[74] The back cover includes a humorous autobiography of Lennon, "About the Awful", again written in his unorthodox style.[75] The book became an immediate best-seller,[76] selling out on its first day.[77] Only 25,000 copies of the first edition were printed, necessitating several reprints, including two in the last week of March 1964 and five more by January 1965.[52] In its first ten months, the book sold almost 200,000 copies,[78] eventually reaching around 300,000 copies bought in Britain.[79] Simon & Schuster published In His Own Write in the US on 27 April 1964,[80] retailing for US$2.50 (equivalent to US$25 in 2023).[81][82] The American edition was identical to the British, except that publishers added the caption "The Writing Beatle!" to the cover.[74] The book was a best-seller in the US,[83] where its publication took place around two months after the Beatles' first visit to the country and amid Beatlemania, the hysteria that surrounded the group.[2]

Contributions by the other Beatles

[edit]McCartney contributed an introduction to In His Own Write,[52] writing that its content was nonsensical yet funny.[84][note 7] In 1964 interviews, Lennon said that two pieces were co-authored with McCartney.[86] Due to a publishing error only "On Safairy with Whide Hunter" was marked as such – being "[w]ritten in conjugal with Paul"[87] – the other piece remaining unidentified.[86]

Beatles drummer Ringo Starr, prone to incorrect wordings and malapropisms – dubbed "Ringoisms" by his bandmates[88] – may have contributed a line to the book.[89] Finishing up after a long day, perhaps 19 March 1964,[89][90] he commented "it's been a hard day", and, on noticing it was dark, added "'s night" ("it's been a hard day's night").[91] While both Lennon and Starr later identified the phrase as Starr's,[92] Lewisohn raises doubts that the phrase originated with him.[89] He writes that if the 19 March dating is correct, that places it after Lennon had already included it in the story "Sad Michael",[89] with the line "He'd had a hard days night that day".[93] By 19 March, copies of In His Own Write had already been printed.[94] Lewisohn suggests that Starr may have previously read or heard it in Lennon's story,[89] while journalist Nicholas Schaffner simply writes the phrase originated with Lennon's poem.[95] Beatles biographer Alan Clayson suggests the phrase's inspiration was Eartha Kitt's 1963 song "I Had a Hard Day Last Night", the B-side of her single "Lola Lola".[96] After director Dick Lester suggested A Hard Day's Night as the title of the Beatles' 1964 film,[97] Lennon used it again in the song of the same name.[98]

Reception

[edit]

In His Own Write received critical acclaim,[76] with favourable reviews in London's The Sunday Times and The Observer.[52] Among the most popular poems in the collection are "No Flies on Frank", "Good Dog Nigel", "The Wrestling Dog", "I Sat Belonely" and "Deaf Ted, Danoota, (and me)".[79] The Times Literary Supplement's reviewer wrote that the book "is worth the attention of anyone who fears for the impoverishment of the English language and British imagination".[99] In The New York Times, Harry Gilroy admired the writing style, describing it as "like a Beatle possessed",[100] while George Melly for The Sunday Times wrote: "It is fascinating of course to climb inside a Beatle's head to see what's going on there, but what really counts is that what's going on there really is fascinating."[101] The Virginia Quarterly Review called the book "a true delight" that finally gave "those intellectuals who have become stuck with Beatlemania ... a serious literary excuse for their visceral pleasures".[102] Gloria Steinem opined in a December 1964 profile of Lennon for Cosmopolitan that the book showed him to be the only one of the band who had "signs of a talent outside the hothouse world of musical fadism and teenage worship".[103]

Though Lennon had never read him, comparisons to Irish writer James Joyce were common.[104] In his review of the book, author Tom Wolfe mentions Spike Milligan as an influence, but writes that the "imitations of Joyce" were what "most intrigued the literati" in America and England: "the mimicry of prayers, liturgies, manuals and grammars, the mad homonyms, especially biting ones such as 'Loud' for 'Lord', which both [Joyce and Lennon] use".[105] In a favourable review for The Nation, Peter Schickele drew comparison to Edward Lear, Carroll, Thurber and Joyce, adding that even those "with a predisposition toward the Beatles" will be "pleasantly shocked" when reading it.[106] Time cited the same influences before admiring the book's typography, written "as if pages had been set by a drunken linotypist".[107] Newsweek called Lennon "an heir to the Anglo-American tradition of nonsense", but found that the constant Carroll and Joyce comparisons were faulty, emphasising instead Lennon's uniqueness and "original spontaneity".[108] Bill Harry published a review in the 26 March 1964 issue of Mersey Beat, written as a parody of Lennon's style.[109][note 8] In an accompanying "translation" of his review, he predicted that while it would "[a]lmost certaintly ... be a best seller", it could lend itself to controversy, with newer Beatles fans likely to be "puzzled by its way-out, off beat and sometimes sick humour".[69]

One of the few negative responses to the book came from the Conservative Member of Parliament Charles Curran.[110] On 19 June 1964, during a House of Commons debate on automation,[111] he quoted the poem "Deaf Ted, Danoota, (and me)", then spoke derisively about the book, arguing that Lennon's verse was a symptom of a poor education system.[112] He suggested that Lennon was "in a pathetic state of near-literacy", adding that "[h]e seems to have picked up bits of Tennyson, Browning, and Robert Louis Stevenson while listening with one ear to the football results on the wireless."[104][note 9] The most unfavourable review of the book came from critic Christopher Ricks,[114] who wrote in New Statesman that anyone unaware of the Beatles would be unlikely to draw pleasure from the book.[115]

Reactions of Lennon and the Beatles

[edit]I really didn't think the book would even get reviewed by the book reviewers ... I didn't think people would accept the book like they did. To tell you the truth they took the book more seriously than I did myself. It just began as a laugh for me.[116]

While the success of In His Own Write pleased Lennon,[18] he was surprised by both the attention it received and its positive reception.[117] In a 1965 interview, he admitted to purchasing all the books that critics compared to his, including one by Lear, one by Geoffrey Chaucer and Finnegans Wake by Joyce. He further stated that he did not see the similarities, except "[perhaps] a little bit of Finnegans Wake ... but anybody who changes words is going to be compared".[118] In a 1968 interview, he said that reading Finnegans Wake "was great, and I dug it and felt as though [Joyce] was an old friend", though he found the book difficult to read in its entirety.[119][note 10]

Among Lennon's bandmates, Starr did not read the book, but Harrison and McCartney enjoyed it.[119] Harrison stated in February 1964 that the book included "some great [gags]",[121] and Lennon recalled McCartney was especially fond of the book, being "dead keen" about it.[119] In Beatles manager Brian Epstein's 1964 autobiography A Cellarful of Noise, he commented: "I was deeply gratified that a Beatle could detach himself completely from Beatleism and create such impact as an author".[122][note 11] Beatles producer George Martin – a fan of The Goon Show[124] – and his wife Judy Lockhart-Smith similarly enjoyed Lennon's writings, with Martin calling them "terribly funny".[125][note 12] In an August 1964 interview, Lennon identified "Scene three Act one" as his favourite piece in the book.[129]

Foyle's Literary Luncheon

[edit]Following the book's publication, Christina Foyle, the founder of Foyles bookshop,[130] honoured Lennon at one of Foyle's Literary Luncheons.[131][132] Osbert Lancaster chaired the event on 23 April 1964 at the Dorchester hotel in London.[133][note 13] Among around six hundred attendees were several eminent guests, including Helen Shapiro, Yehudi Menuhin and Wilfrid Brambell.[135][note 14] Hungover from a night spent at the Ad Lib Club,[136] Lennon admitted to a journalist at the event that he was "scared stiff".[18] He was reluctant to perform the expected speech, getting Epstein to advise luncheon organisers Foyle and Ben Perrick the day before the event that he would not be speaking. The two were taken aback, but assumed that Lennon meant he would only provide a short speech.[135]

At the event, after Lancaster introduced him,[135] Lennon stood and only said: "Uh, thank you very much, and God bless you. You've got a lucky face."[136] Foyle was irritated,[133] while Perrick recalls there was "some slight feeling of bewilderment" among attendees.[137] Epstein gave a speech to avoid further disappointing any diners that had hoped to hear from Lennon.[130] In A Cellarful of Noise, Epstein expressed of Lennon's lack of a speech: "He was not prepared to do something which was not only unnatural to him, but also something he might have done badly. He was not going to fail."[138] Perrick reflects that Lennon retained the affection of his audience due to his "charm and charisma", with attendees still happily queuing afterwards for signed copies.[139]

Analysis

[edit]Against Lennon's songwriting

[edit]You just stick a few images together, thread them together, and you call it poetry. But I was just using the mind that wrote In His Own Write to write that song.[140]

Later commentators have discussed the book's prose in relation to Lennon's songwriting, both in how it differed from his contemporary writing and in how it anticipates his later work.[141] Writer Chris Ingham describes the book as "surreal poetry",[142] displaying "a darkness and bite ... that was light years away from 'I Want to Hold Your Hand'".[117] Professor of English Ian Marshall describes Lennon's prose as "mad wordplay", noting the Lewis Carroll influence and suggesting it anticipates the lyrics of later songs like "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" and "I Am the Walrus".[143] Critic Tim Riley compares the short story "Unhappy Frank" to "I Am the Walrus", though he calls the former "a good deal more oblique and less cunning".[84]

Walter Everett describes the book as including "Joycean dialect substitutions, Carrollian portmanteau words, and rich-sounding stream-of-consciousness double-entendre".[79] Unlike Carroll, Lennon generally did not create new words in his writing, but instead used homonyms (such as grate for great) and other phonological and morphological distortions (such as peoble for people).[144] Both Everett and Beatles researcher Kevin Howlett discuss the influence of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass on both of Lennon's books and on the lyrics for "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds".[145] Everett singles out the poems "Deaf Ted, Danoota, (and me)" and "I Wandered" as examples of this influence,[146] quoting an excerpt from "I Wandered" to illustrate this:[147]

Past grisby trees and hulky builds

Past ratters and bradder sheep

...

Down hovey lanes and stoney claves

Down ricketts and stickly myth

In a fatty hebrew gurth

I wandered humply as a sock

To meet bad Bernie Smith

In his book Can't Buy Me Love, Jonathan Gould compares the poem "No Flies on Frank" to Lennon's 1967 song "Good Morning Good Morning", seeing both as illustrating the "dispirited domestic milieu" of "protagonists [who] drag themselves through the day 'crestfalled and defective'".[148] Everett suggests that while the character Bungalow Bill in Lennon's 1968 song "The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill" is generally understood to be a portmanteau of Jungle Jim and Buffalo Bill, the name also could have its origins in the character Jumble Jim from Lennon and McCartney's short story "On Safairy with Whide Hunter".[149]

On 23 March 1964 – the same day the book was published in the UK – Lennon went to Lime Grove Studios, West London, to film a segment promoting it. The BBC programme Tonight broadcast the segment live, with presenters Cliff Michelmore, Derek Hart and Kenneth Allsop reading excerpts.[150] A four-minute interview between Allsop and Lennon followed,[150] with Allsop challenging him to try using similar wordplay and imagination in his songwriting.[151][152] Similar questions about the banality of his song lyrics – including from musician Bob Dylan[26][153] – became common following the publication of his book,[154] pushing him to write deeper, more introspective songs in the years that followed.[155][156] In a December 1970 interview with Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone, Lennon explained that early in his career he made a conscious split between writing pop music for public consumption and the expressive writing found in In His Own Write, with the latter representing "the personal stories ... expressive of my personal emotions".[157] In his 1980 Playboy interview, he recalled the Allsop interview as being the impetus for his writing "In My Life".[158] Writer John C. Winn mentions songs like "I'm a Loser", "You've Got to Hide Your Love Away" and "Help!" as exemplifying Lennon's move to deeper writing in the year after the book.[155] Music scholar Terence O'Grady describes the "surprising twists" of Lennon's 1965 song "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)" as more similar to In His Own Write than his earlier songs,[159] and Sauceda mentions several of Lennon's later Beatles songs – including "I Am the Walrus", "What's the New Mary Jane", "Come Together", "Dig a Pony" – as demonstrating his ability for "sound-sense writing", where words are assembled not for their meaning but instead for their rhythm and for "the joy of sound".[160]

James Sauceda and Finnegans Wake

[edit]Sauceda produced the only comprehensive study of Lennon's writings in his 1983 book Literary Lennon: A Comedy of Letters,[161] providing a postmodern dissection of both In His Own Write and Lennon's next book of nonsense literature, A Spaniard in the Works.[162] Everett describes the book as "a thorough but sometimes wrongheaded postmodern Finnegans Wake-inspired parsing".[163] Sauceda, for example, casts doubt on Lennon's claim that he had never read Joyce before writing In His Own Write.[164] He suggests that the lines "he was debb and duff and could not speeg"[165] and "Practice daily but not if you are Mutt and Jeff"[166] from the pieces "Sad Michael" and "All Abord Speeching", respectively, were influenced by a passage from Finnegans Wake discussing whether someone is deaf or deaf-mute, reading:[167]

Jute. – Are you jeff?

Mutt. – Somehards.

Jute. – But are you not jeffmute?

Mutt. – Noho. Only an utterer.

Jute. – Whoa? Whoat is the mutter with you?

Author Peter Doggett is even more dismissive of Sauceda than Everett, criticising Sauceda for missing references to British popular culture.[161] In particular, he mentions the analysis of the story "The Famous Five Through Woenow Abbey", wherein Sauceda concludes that the Famous Five of the story refers to Epstein and the Beatles,[168] but does not mention the popular British children's novels The Famous Five, written by Enid Blyton[161] – referred to as "Enig Blyter" in Lennon's story.[169] Riley calls Sauceda's insights "keen", but suggests more can be understood by analysing the works with reference to Lennon's biography.[170] Gould comments that The Goon Show was Lennon's closest experience to the style of Finnegans Wake, and describes Milligan's 1959 book Silly Verse for Kids as "the direct antecedent to In His Own Write."[112]

Against Lennon's biography

[edit]I used to hide my real emotions in gobbledegook, like In His Own Write. When I wrote teenage poems, I wrote in gobbledegook because I was always hiding my real emotions from [my aunt] Mimi [Smith].[18]

Before he signed with Jonathan Cape, Lennon wrote prose and poetry to keep for himself and share with his friends, leaving his pieces filled with private meanings and in-jokes.[171] Quoted in a February 1964 piece in Mersey Beat, Harrison said with regard to the book that "[t]he 'with-it' people will get the gags and there are some great ones".[121] Lewisohn states that Lennon based the story "Henry and Harry" on an experience of Harrison, whose father gifted him electrician's tools for Christmas 1959, implying he expected his son to become an electrician despite Harrison's disagreement.[172] In the story, Lennon writes that such jobs were "brummer striving", explaining in a 1968 television interview that the term referred to "all those jobs that people have that they don't want. And there's probably about 90 percent brummer strivers watching in at the moment."[173] The 1962 story "Randolf's Party" was never discussed by Lennon, but Lewisohn suggests he most likely wrote it about former Beatles drummer Pete Best. Lewisohn mentions similarities between Best and the lead character, including an absent father figure and Best's first name being Randolf.[174] Best biographer Mallory Curley describes the lines "We never liked you all the years we've known you. You were never raelly [sic] one of us you know, soft head" as, "the crux of Pete's Beatles career, in one paragraph."[175]

Riley opines that the short story "Unhappy Frank" can be read as Lennon's "screed against 'mother'", aimed at both his aunt Mimi and late-mother Julia for their over-protectiveness and absence, respectively.[170] The poem "Good Dog Nigel" tells the story of a happy dog that is put down. Riley suggests it was inspired by Mimi putting down Lennon's dog, Sally, and that the dog in the poem shares its name with Lennon's childhood friend Nigel Walley, a witness to Julia's death.[170] Prone to hitting his girlfriends as a teenager,[176] Lennon also included several domestic violence allusions in the book, such as "No Flies on Frank", where a man beats his wife to death and then tries to deliver the corpse to his mother-in-law.[117][note 15] In his book The Lives of John Lennon, author Albert Goldman interprets the story as relating to Lennon's feelings about his wife Cynthia and Mimi.[179]

Sauceda and Ingham comment that the book includes several references to "cripples", Lennon having had developed phobias of physical and mental disabilities as a child.[36][117] Thelma Pickles, Lennon's girlfriend in the autumn of 1958,[180] later recalled he would joke with disabled people he encountered in public, including "[accosting] men in wheelchairs and [jeering], 'How did you lose your legs? Chasing the wife?'"[181] In an interview with Hunter Davies for The Beatles: The Authorised Biography, Lennon admitted that he "did have a cruel humor", suggesting it was a way of hiding his emotions. He concluded: "I would never hurt a cripple. It was just part of our jokes, our way of life."[182] During the Beatles' tours, people with physical handicaps were often brought to meet the band, with some parents hoping that their child being touched by a Beatle would heal them.[36][183] In his 1970 interview with Rolling Stone, Lennon remembered, "[w]e were just surrounded by cripples and blind people all the time and when we would go through corridors they would be all touching us. It got like that, it was horrifying".[184] Sauceda suggests that these strange recent experiences led to Lennon to incorporating them into his stories.[36] For Doggett, the essential qualities of Lennon's writing are "cruelty, [a] matter-of-fact attitude to death and destruction, and [a] quick descent from bathos into gibberish".[185]

Anti-authority and the Beat movement

[edit]One of the reviews of In His Own Write tried to put me in this satire boom with Peter Cook and those people that came out of [the University of] Cambridge, saying, "Well, he's just satirising the normal things, like the Church and the State," which is what I did. Those are the things that keep you satirising, because they're the only things.[186]

In His Own Write includes elements of anti-authority sentiment,[26] disparaging both politics and Christianity, with Lennon recalling that the book was "pretty heavy on the church" with "many knocks at religion" and includes a scene depicting a dispute between a worker and a capitalist.[36] Riley suggests that contemporary reviewers were overtaken by the book's "loopy, scabrous energy", overlooking the "subversion [which] lay embedded in its cryptic asides".[187] The story "A letter", for example, references Christine Keeler and the Profumo affair, featuring a drawing of her and the closing line,[188] "We hope this fires you as you keeler."[189]

Lennon and his best friend in art college, Stu Sutcliffe,[190] often discussed writers like Henry Miller, Jack Kerouac and other Beat poets, such as Gregory Corso and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.[191] Lennon, Sutcliffe and Harry sometimes interacted with the local British beat scene,[192] and, in June 1960, the Beatles – then known as the Silver Beetles[193] – provided musical backing for the beat poet Royston Ellis during a poetry reading at the Jacaranda coffee bar in Liverpool.[38][194] While Lennon suggested in a 1965 interview that if he had not been a Beatle he "might have been a Beat Poet",[18] author Greg Herriges declares that In His Own Write's irreverent attacks on the mainstream ranked Lennon among the best of his predecessors in the Beat Generation.[195] Journalist Simon Warner disagrees, positing that Lennon's writing style owed little to the Beat movement, being instead largely derived from the nonsense tradition of the late nineteenth century.[196]

Illustrations

[edit]

The illustrations of In His Own Write have received comparatively little attention.[197] Doggett writes that the book's drawings are similar to the "shapeless figures" of Thurber, but with Lennon's unique touch.[161] He interprets much of the art as displaying the same fascination with cripples apparent in the text, joining faces to "unwieldy, joke-animal bodies" alongside figures "distorted almost beyond humanity".[161] Journalist Scott Gutterman describes the characters as "strange, protoplasmic creatures",[198] and "lumpen everyman and everywoman figures" joined by animals, "[gamboling] around an empty landscape, engaged in obscure pursuits".[199]

Analysing the illustration accompanying the piece "Randolf's Party", Gutterman describes the group as "gossiping, frowning, and bunching together", but while some figures adhere to regular social conventions, some fly away out of the image.[199] Doggett interprets the same drawing as including "Neanderthal men", some merely faces attached to balloons, while others "[boast] Cubist profiles with one eye hovering just outside their faces".[161] Sauceda suggests the figures of the drawing reappear in the Beatles' 1968 animated film, Yellow Submarine, and describes the "balloon heads" as a metaphor for people's "empty-headedness".[200] Doggett and Sauceda each identify self-portraits among Lennon's drawings, including one of a Lennon-like figure flying through the air, which Doggett determines to be one of the book's best illustrations.[161][201] Doggett interprets it as evoking Lennon's "wish-fulfillment dreams",[161] while Sauceda and Gutterman each see the drawing as representing the freedom Lennon felt in making his art.[199][202]

Legacy

[edit]Cultural commentators of the 1960s often focused on Lennon as the leading artistic and literary figure in the Beatles.[203] In her study of Beatles historiography, historian Erin Torkelson Weber suggests that the publication of In His Own Write reinforced these perceptions, with many viewing Lennon as "the smart one" of the group, and that the band's first film, A Hard Day's Night, further emphasised that view.[204] Everett arrives at similar conclusions, writing that, however unfairly, Lennon was often described as more artistically adventurous than McCartney in part because of the publication of his two books.[205] Communications professor Michael R. Frontani states that the book served to further distinguish Lennon's image within the Beatles,[206] while Independent writer Andy Gill felt that it and A Spaniard in the Works revealed Lennon to be "the sharpest Beatle, a man of acid wit".[207]

Beatles writer Kenneth Womack suggests that, paired with the Beatles' debut film, the book challenged the band's "non-believers", made up of those outside their then largely teenage fanbase,[208] a contention with which philosophy professor Bernard Gendron agrees, writing that the two pieces of media initiated "a major reversal of the public assessment of the Beatles' aesthetic worth."[209] Doggett groups the book with the Beatles' more general move from the "classic working-class pop milieu" towards "an arty middle-class environment". He argues that the band's invitation into the British establishment – such as their interactions with photographer Robert Freeman, director Dick Lester and publisher Tom Maschler, among others – was unique for pop musicians of the time and threatened to erode elements of the British class system.[210] Prince Philip of the British royal family read the book and said he enjoyed it thoroughly,[83] while Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau described Lennon in 1969 as "a pretty good poet".[211] The book resulted in numerous businesses and charities requesting that Lennon produce illustrations.[212][note 16] In 2014, the broker Sotheby's auctioned over one hundred of Lennon's manuscripts for In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works from Maschler's collection. The short stories, poems and line drawings sold for US$2.9 million (US$3.7 million adjusted for inflation), more than double their pre-sale estimate.[215]

Lennon issuing a book of poetry before Bob Dylan subverted expectations in Britain, where Lennon was still seen as a simple pop star and Dylan was lauded as a poet.[187] Inspired by In His Own Write, Dylan began his first book of poetry in 1965, later published in 1971 as Tarantula.[216][note 17] Using similar wordplay, though with fewer puns, Dylan described it contemporaneously as "a John Lennon-type book".[220] Dylan biographer Clinton Heylin suggests that Lennon's piece "A Letter" is the most overt example of In His Own Write's influence on Tarantula, with several similar satirical letters appearing in Dylan's collection.[216] Three volumes of Dylan's personal writings were later booklegged under the title In His Own Write: Personal Sketches, released in 1980, 1990 and 1992.[221] Beyond influencing Dylan, the book also inspired Michael Maslin, a cartoonist for The New Yorker magazine. A fellow Thurber enthusiast, he identified it, particularly the piece "The Fat Growth of Eric Hearble", as his introduction to "crazy wacky humor".[222]

Other versions

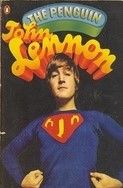

[edit]The Penguin John Lennon

[edit]

In 1965, Lennon published a second book of nonsense literature, A Spaniard in the Works, expanding on the wordplay and parody of In His Own Write.[223][224] While it was a best-seller,[76] reviewers were generally unenthusiastic, considering it similar to his first book yet without the benefit of being unexpected.[225] He began a third book, planned for release in February 1966, but abandoned it soon after,[226] leaving the two books the only ones published in his lifetime.[227][note 18]

In what Doggett terms "an admission that his literary career was at an end", Lennon consented to both of his books being joined into a single paperback.[231] On 27 October 1966, Penguin Books published The Penguin John Lennon.[231][232] The first edition to join both of his books into one volume,[233] the publishers altered the proportions of several illustrations in the process.[231] The art director of Penguin Books, Alan Aldridge, initially conceived that the cover would consist of a painting depicting Lennon as a penguin, but the publishing director rejected the idea as disrespectful to the company.[233] Aldridge commissioned British photographer Brian Duffy to take a cover photo with Lennon posing next to a birdcage.[234] On the day of photoshoot, Aldridge changed his mind and instead had Lennon dress as the comic book character Superman, with the imagery meant to suggest he had now conquered music, film and literature. DC Comics, the owners of the Superman franchise, claimed the image infringed on their copyright, so Aldridge retouched the photo, replacing the S on the costume's shield with Lennon's initials.[235] At least two more covers were used in the next four years; one shows Lennon wearing several pairs of glasses, while the 1969 edition shows a portrait of Lennon with long hair and a beard.[231]

Translations

[edit]In His Own Write has been translated into several different languages.[83] Authors Christiane Rochefort and Rachel Mizraki translated the book into French,[236] published in 1965 as En flagrant délire[237] with a new humorous preface titled "Intraduction [sic] des traditrices".[238] Scholar Margaret-Anne Hutton suggests that the book's irreverence, black humour and anti-establishment stance pairs well with Rochefort's style and that its wordplay anticipates that of her 1966 book, Une Rose pour Morrison.[239] The book was translated into Finnish by the translator responsible for adapting the works of Joyce.[83]

Author Robert Gernhardt attempted to convince Arno Schmidt – who later worked on Joyce translations – to translate In His Own Write into German, but Schmidt rejected the offer.[240] Instead, publisher Helmut Kossodo and Wolf Dieter Rogosky each translated some parts of the work,[240] publishing a bilingual German/English version, In seiner eigenen Schreibe, in 1965.[241] Author Karl Bruckmaier published a new edition in 2010,[242] updating several cultural references in the process.[240][note 19] Argentine author Jaime Rest translated the book into Spanish in the 1960s as En su tinta,[245] using a Buenos Aires urban-dialect.[246] Andy Ehrenhaus published a bilingual Spanish/English edition of both In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works in 2009,[247] with his strategy of imagining Lennon as writing in Spanish described by one commentator as "lunatically effective".[248]

Adaptations

[edit]The Lennon Play: In His Own Write

[edit]Writing (1966–1968)

[edit]When Lennon began writing A Spaniard in the Works, he considered making a spoken-word LP with extracts from In His Own Write but ultimately decided against it.[249][250] In 1966, Theodore Mann, the artistic director of New York City's Circle in the Square, commissioned American playwright Adrienne Kennedy to write a new play. Kennedy came up with the idea of adapting Lennon's two books for the stage, flying to London to discuss the idea with Jonathan Cape.[251] Around the end of 1967, actor Victor Spinetti began working with Kennedy to adapt the two books into a one-act play.[252] Spinetti had acted in the Beatles' films A Hard Day's Night, Help! and Magical Mystery Tour,[253] and became good friends with Lennon.[254] Originally titled Scene Three, Act One after one of In His Own Write's stories and staged under that name in late-1967, the play's title was changed to The Lennon Play: In His Own Write.[255] The play joins elements of the books together to tell the story of an imaginative boy growing up,[256] escaping from the mundane world through his daydreaming.[26] Lennon sent notes and additions for the play to Spinetti,[257] and held final approval on Spinetti and Kennedy's script.[26] Kennedy was let go from the project before it was finished.[258][note 20]

On 3 October 1967, the National Theatre Company in London announced that they would be staging an adaption of Lennon's two books.[260] The next month, on 24 November, Lennon compiled effects tapes at EMI Recording Studios for use in the production. Returning on 28 November for a Beatles recording session, he recorded speech and sound effects, working past midnight from 2:45 am to 4:30 am.[261] Spinetti attended the session to assist Lennon in preparing the tapes.[262][note 21] Sir Laurence Olivier produced the show, while Spinetti directed.[264] Riley writes Adrian Mitchell collaborated on the production but does not specify in what capacity.[265] In the spring of 1968, Spinetti and Lennon discussed ways the show could be performed, and in the summer Lennon attended several rehearsals of the show between sessions for the Beatles' eponymous album,[266] also known as "the White album".[267] In a June 1968 interview, he stated that "[w]hen I saw the rehearsal, I felt quite emotional ... I was too involved with it when it was written ... it took something like this to make me see what I was about then".[268] A little over a week before its opening, Lennon recorded twelve more tape loops and sound effects for use in the play, copying them and taking the tape at the end of the session.[269]

Premiere (June 1968)

[edit]The play opened at The Old Vic theatre in London on 18 June 1968,[270] and Simon & Schuster published it the same year.[271][272] It was heavily censored due to lines perceived as blasphemous and disrespectful to world leaders,[273] including a speech from the Queen titled "my housebound and eyeball".[274][note 22] Lennon was enthusiastic about it;[275] Spinetti later recalled Lennon excitedly running up to him after the first night's performance, expressing that the play reminded him of his early enthusiasm for writing.[268][276] Reception to the play however was mixed.[277] Reviewing it for The New York Times, critic Martin Esslin described it as "ingenious and skillful, but ultimately less than satisfying" due to the lack of any underlying meaning.[278] Sauceda retrospectively dismisses the play as a weak adaption that struggles to generate "thematic momentum".[279] He criticises "many awkward and pointless attempts to ape Lennon's style" by Spinetti and Kennedy that "[infringe] on the integrity of John Lennon's work".[280] For example, he writes that they changed Lennon's pun "Prevelant ze Gaute"[281] – a play on French leader Charles de Gaulle – to "Pregnant De Gaulle".[280][note 23]

Though they were both still married to other people, Yoko Ono joined Lennon at the opening performance in one of their first appearances in public together.[283][note 24] Some journalists challenged the couple, shouting "Where's your wife?" at Lennon, in reference to Cynthia.[285][286] Cynthia, then holidaying in Italy with her family and her and Lennon's son, Julian, saw photos of the couple attending the premiere in an Italian newspaper.[286][287] In an interview with Ray Coleman, she recalled, "I knew when I saw the picture that that was it", concluding that Lennon would only have brought Ono out in public if he was prepared for a divorce.[288][note 25] The ensuing controversy over Lennon and Ono's appearance drew press attention away from the play.[275] Everett writes the couple were "lambasted in very hurtful ways by the press, often from an openly racist perspective".[283] Ono biographer Jerry Hopkins suggests the couple's first experiment with heroin in July 1968 was in part due to the pain they experienced from their treatment by the press,[289] an opinion Beatles writer Joe Goodden shares, though he writes that they first used the drug together in May 1968.[290]

Other adaptations

[edit]Lennon briefly considered adapting his two books into a film,[291] announcing at a 14 May 1968 press conference that Apple Corps would be producing it within the year.[292] Besides The Lennon Play, playwright Jonathan Glew directed the book's only other adaption in 2015 after acquiring permission from Lennon's widow, Ono.[293] Staged at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe,[293] the production consisted of a dramatic reading of all of the book's pieces.[294]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Lennon chose Carroll for inclusion on the album cover of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967.[6][7]

- ^ Lewisohn states it was Lennon's first poem but does not date it.[14] It was later included in the 68th issue of Mersey Beat,[15] published on 27 February 1964[14] as "The Land of Lunapots" alongside his poem "The Tales of Hermit Fred".[16]

- ^ Both Harry and Lennon have each claimed responsibility for coming up with the name "Beatcomber".[40]

- ^ While acknowledging the deliberate misspellings which characterise Lennon's writings, Lewisohn suggests that the title "Small Sam" may have been a misprint on the part of Mersey Beat, given that the central character's name, Small Stan, is spelled as such fourteen times in the 150 word story.[45] A piece in the 30 July 1964 issue of Mersey Beat quotes Lennon in calling the piece "Small Stan".[46]

- ^ Left Hand Left Hand was a reference to the book Left Hand, Right Hand! by Osbert Sitwell,[52][56] and Stop One and Buy Me was a play on ice-cream carts that advertise "Stop Me and Buy One".[56]

- ^ When originally published in the 14 September 1961 issue of Mersey Beat, Lennon's piece "Around And About" recounted fictional Liverpool landmarks,[62] including the "Casbin" and "Jackarandy" clubs (playing on the Casbah Club and the Jacaranda, respectively).[62][63] When he published In His Own Write, he included the piece under the new title "Liddypool", omitting the list of attractions and the following sentences:[64]

"We've been engaged for 43 years and he still smokes. I am an unmurdered mother of 19 years, am I pensionable? My dog bites me when I bite it."

- ^ Submitting the introduction to the publisher, McCartney wrote: "Dear Mr Cape, there are only 234 words but I don't care." A publisher employee attempted to rewrite it, but McCartney's original was the version published.[85]

- ^ In Literary Lennon, Sauceda presents excerpts of Harry's review, along with his interpretation of its content.[109]

- ^ During the debate, Curran's fellow Conservative MP Norman Miscampbell responded to the complaints. Disputing that Lennon was poorly educated, he described the Beatles on the whole as "highly intelligent, highly articulate and highly engaging", and added that it would be wrong to assume their success "came from anything other than great skill".[113]

- ^ In an undated quotation, Lennon stated that reading Joyce for the first time was "like finding Daddy".[120]

- ^ Derek Taylor, the Beatles' press officer, ghostwrote A Cellarful of Noise after extensively interviewing Epstein.[123]

- ^ Martin produced albums for The Goon Show's individual members, including one for Milligan in late 1961.[126] While some sources state that Martin produced albums for the group,[127] Lewisohn clarifies that this is a popular misconception, since Martin only recorded the three Goons individually or during a collaboration.[128]

- ^ At the same time, the other Beatles filmed the closing sequence of "Can't Buy Me Love" for A Hard Day's Night, leaving Lennon absent from the scene in the completed film.[134]

- ^ Other guests included Mary Quant, Millicent Martin, Harry Secombe, Marty Wilde, Arthur Askey, Joan Littlewood, Victor Silvester, Carl Giles,[133] Alma Cogan, Dora Bryan, Lionel Bart, Cicely Courtneidge and Colin Wilson.[135]

- ^ In The Beatles: The Authorised Biography, Lennon stated: "I was in a blind rage for two years. I was either drunk or fighting. There was something the matter with me".[177] In his 1980 interview with Playboy, he said that "hitting females is something I'm always ashamed of and still can't talk about – I'll have to be a lot older before I can face that in public, about how I treated women as a youngster".[178]

- ^ The only offer Lennon accepted was to design a Christmas card for the charity Oxfam.[212] The illustration depicts a spherical robin,[212] and is the same drawing that accompanies the piece "The Fat Budgie" in A Spaniard in the Works.[213] Doggett writes that roughly half a million cards were first issued on 19 September 1964,[212] though author Steve Turner writes the card was printed for Christmas 1965.[213] Some at Oxfam felt the card to be in poor taste. The Reverend Frederick Nickalls of Barnehurst, Kent, complained that it "has nothing to do with Christmas. ... Those old world pictures of stage coaches, snow and candles are more Christian than The Fat Budgie."[214]

- ^ Dylan stated in 2001 that his manager Albert Grossman signed him up to write the book without consulting him.[217] Journalist Colin Irwin also suggests that Dylan was commissioned to write the work,[218] but Heylin disputes this, stating that Grossman's role only extended to discussions with publishing companies and that Dylan was enthusiastic about the project.[219]

- ^ In 1986, Harper & Row published Skywriting by Word of Mouth, a posthumous collection of his unreleased writings,[228] most of which were made during his "house-husband" period in the late 1970s.[229] Doggett comments that the book's writing style differs greatly from In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works, relying much more on sardonic humour.[230]

- ^ For example, he attempted to "pimp up"[243] the text by replacing a reference to German football manager "Sepp Berserker" (Sepp Herberger) with "Maharishi Mahesh Löwi" (Jogi Löw).[240]Both German translations have received praise,[243][244] but also criticism. Literary scholar and translator Friedhelm Rathjen describes them as "one-dimensional" and criticises that the title's wordplay on "in his own right" is not reflected in the translation.[240]

- ^ Kennedy detailed a real and fictional account of her experience writing the play in her 1990 book Deadly Triplets.[259] She later dramatised her involvement in the adaption with her 2008 Off-Broadway play, Mom, How Did You Meet the Beatles?[251]

- ^ Spinetti has a cameo on "Christmas Time (Is Here Again)",[263] recorded during the same session for the Beatles' 1967 Christmas record.[262]

- ^ Some of the world leaders referenced include Harold Macmillan, Selwyn Lloyd, James Callaghan, Edward Heath, Frank Cousins and George Woodcock. Lennon's poem "The Farts of Mousey Dung" is likely a play on "The Thoughts of Mao-Tse-tung".[274]

- ^ He also disparages Beatles writers Philip Norman and Anthony Fawcett, who incorrectly cite "Pregnant De Gaulle" as Lennon's original pun.[282]

- ^ Author Barry Miles writes it was the couple's second public appearance and that the first happened three days earlier, planting an acorn during an event at Coventry Cathedral.[270] Lewisohn states it was the couple's third public appearance.[284]

- ^ A few days later, Magic Alex, a close associate of Lennon and the Beatles, travelled to Italy and notified Cynthia that Lennon planned to divorce her.[286][288]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Lewisohn 2013, p. 68.

- ^ a b Howlett & Lewisohn 1990, p. 40.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, p. 43.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2013, p. 49.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2013a, p. 131.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 332n34.

- ^ Howlett 2017, pp. 111, 117.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 8, 49.

- ^ Turner 2005, p. 123.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, p. 8.

- ^ Shotton & Schaffner 1983, p. 33.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 49, 807n25.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 140.

- ^ a b c Lewisohn 2013, p. 807n25.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 138.

- ^ Harry 1977, p. 76.

- ^ Carroll 1871, p. 21, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. 140.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k The Beatles 2000, p. 134.

- ^ Miles 1998, p. 606.

- ^ Everett 2001, p. 15.

- ^ Laing 2009, pp. 12, 23, 256n14.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 9, 59.

- ^ Turner 2005, p. 123: establishment figures, surreal humour; Lewisohn 2013, p. 59: admired, punning wordplay; Lennon 1973, p. 8, quoted in Lewisohn 2013, p. 59: "the only proof ..."

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2013, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Gutterman 2014, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e Winn 2009, p. 173.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013a, pp. 131, 758n67.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013a, p. 758n67.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, pp. 147, 155.

- ^ Sheff 1981, quoted in Lewisohn 2013, p. 59.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 125–126, 137.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2013, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Howlett & Lewisohn 1990, p. 42.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 143–144, 422–423.

- ^ Clayson 2003, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e Sauceda 1983, p. 22.

- ^ a b The Beatles 2000, p. 62.

- ^ a b Laing 2009, p. 17.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2013, p. 455.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013a, p. 1549n103.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, p. 805n23.

- ^ a b c Lewisohn 2013a, p. 1272.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, p. 667.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013a, p. 1590n86.

- ^ Harry 1964b, quoted in Harry 1977, p. 87.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 148, quoted in Lewisohn 2013, p. 667.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 8–9: Alice in Wonderland and The Goon Show; Miles 1998, p. 606: Thurber.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, p. 194.

- ^ a b c Savage 2010, p. vii.

- ^ Harris 2004, p. 119: Began following during autumn tour; Winn 2008, p. 328: Love Me Do: The Beatles' Progress.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Savage 2010, p. viii.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, p. 134: "An awful lot of the material was written while we were on tour, most of it when we were in Margate"; Lewisohn 2000, p. 116: Margate residency from 8 to 13 July 1963.

- ^ a b Davies 1968, p. 226.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 232.

- ^ a b Norman 2008, p. 359.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 195.

- ^ Lennon 2014, pp. 20–21, 38–41, 61.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 241–242, 423, 475, 667, 788 and Lewisohn 2013a, pp. 465, 964, 1420, 1550n103: previously written, with years; Lennon 2014, pp. 16–19, 29–31, 54, 62–63, 66–67, 78: included in In His Own Write.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013a, pp. 465, 955.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 172, 822n37.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2013a, p. 964.

- ^ Doggett 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013a, p. 1550n103: included in In His Own Write as "Liddypool", coffee shops removed; Doggett 2005, pp. 21–22: included in In His Own Write as "Liddypool", "We've been engaged ..." removed.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 44–45.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 50.

- ^ Goldman 1988, p. 45.

- ^ Watkins 1983, p. 77.

- ^ a b Harry 1964a, quoted in Harry 1977, p. 78.

- ^ Ricks 1964, p. 684.

- ^ Winn 2008, p. 106.

- ^ Davies 2012, p. 75.

- ^ Ingham 2009, p. 220.

- ^ a b Sauceda 1983, p. 24.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c Burns 2009, p. 221.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 5.

- ^ Savage 2010, p. ix.

- ^ a b c Everett 2001, p. 218.

- ^ Winn 2008, p. 107.

- ^ Anon.(b) 1964, p. E7.

- ^ Anon.(c) 1964, p. cxxx.

- ^ a b c d Schaffner 1977, p. 27.

- ^ a b Riley 2011, p. 262.

- ^ Aspden 2014.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2013, p. 822n37.

- ^ Lennon 2014, p. 9, quoted in Lewisohn 2013, p. 822n37.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, p. 129.

- ^ a b c d e Lewisohn 2000, p. 155.

- ^ Miles 2007, pp. 116–117.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, pp. 154–155.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, p. 129: Starr; Sheff 1981, quoted in The Beatles 2000, p. 129: Lennon.

- ^ Lennon 2014, p. 35.

- ^ Winn 2008, p. 164.

- ^ Schaffner 1977, p. 39.

- ^ Clayson 2003a, p. 380, quoted in Womack 2016, p. 185.

- ^ Sheff 1981, quoted in The Beatles 2000, p. 129.

- ^ Everett 2001, p. 235.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 3, quoted in Riley 2011, p. 261.

- ^ Gilroy 1964, p. 31.

- ^ Melly 1964, quoted in Savage 2010, p. xn2.

- ^ Anon.(c) 1964, p. cxxx, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. 5.

- ^ Steinem 1964, quoted in Steinem 2006, p. 61.

- ^ a b Harris 2004, p. 119.

- ^ Wolfe 1964, quoted in Harris 2004, p. 119.

- ^ Schickele 1964, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. 4.

- ^ Anon.(b) 1964, p. E7, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. 4.

- ^ Anon.(a) 1964, quoted in Sauceda 1983, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Sauceda 1983, pp. 5–7.

- ^ MacDonald 2007, p. 23.

- ^ Thomson & Gutman 2004, p. 47.

- ^ a b Gould 2007, p. 233.

- ^ Thomson & Gutman 2004, p. 49.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 7.

- ^ Ricks 1964, p. 685, quoted in Sauceda 1983, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Ingham 2009, p. 221.

- ^ Howlett & Lewisohn 1990, p. 44.

- ^ a b c The Beatles 2000, p. 176.

- ^ Ingham 2009, p. 221; Harris 2004, p. 119; Riley 2011, p. 262.

- ^ a b Sauceda 1983, p. 16.

- ^ Epstein 1964, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. xix.

- ^ Weber 2016, p. 32.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, p. 259.

- ^ Womack 2017, p. 245.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 259, 509.

- ^ Laing 2009, p. 256n14.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, p. 259n.

- ^ Winn 2008, p. 227.

- ^ a b Howlett & Lewisohn 1990, p. 43.

- ^ Perrick 2004, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Lewisohn 2009, p. 33.

- ^ a b c Miles 2007, p. 122.

- ^ Lewisohn 2000, p. 158.

- ^ a b c d Perrick 2004, p. 43.

- ^ a b Winn 2008, p. 173.

- ^ Perrick 2004, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Epstein 1964, quoted in The Beatles 2000, p. 134.

- ^ Perrick 2004, p. 44.

- ^ Sheff 1981, p. 194, quoted in The Beatles 2000, p. 273.

- ^ Ingham 2009, p. 25: difference from contemporary writing; Marshall 2006, p. 17: anticipation of later songwriting.

- ^ Ingham 2009, p. 25.

- ^ Marshall 2006, p. 17.

- ^ Dewees 1969, pp. 291, 293.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 104, 332n34; Howlett 2017, p. 55.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 104, 332n34.

- ^ Lennon 2014, p. 36, quoted in Everett 1999, p. 332n34.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 410.

- ^ Everett 2001, pp. 168, 344n75.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2000, p. 152.

- ^ Winn 2008, p. 327.

- ^ MacDonald 2007, p. 169.

- ^ Frontani 2007, pp. 82, 113–114.

- ^ Everett 2001, p. 254.

- ^ a b Winn 2008, pp. 327–328.

- ^ Turner 2005, p. 60.

- ^ Wenner 1971, pp. 124–126, quoted in Everett 1999, p. 306.

- ^ Sheff 1981, pp. 163–164, quoted in Everett 2001, p. 319.

- ^ O'Grady 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, pp. 44–45, 139.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Doggett 2005, p. 49.

- ^ Everett 2001, pp. 396n26, 429.

- ^ Everett 2001, p. 396n26.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 18.

- ^ Lennon 2014, p. 35, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. 44.

- ^ Lennon 2014, p. 45, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. 44.

- ^ Joyce 1939, pp. 16.12–16, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. 44.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 41, quoted in Doggett 2005, p. 49.

- ^ Lennon 2014, p. 32, quoted in Doggett 2005, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Riley 2011, p. 263.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, pp. 16, 23.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, p. 241.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, p. 242.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, p. 788.

- ^ Curley 2005, p. 22, quoted in Lewisohn 2013, p. 788.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Davies 1968, p. 59, quoted in Lewisohn 2013, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Sheff 1981, quoted in Lewisohn 2013, p. 208.

- ^ Goldman 1988, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, p. 190.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1995, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Davies 1968, p. 56.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1995, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Wenner 1971, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. 22.

- ^ Doggett 2005, p. 21.

- ^ Wenner 1971, quoted in The Beatles 2000, p. 176.

- ^ a b Riley 2011, p. 261.

- ^ Riley 2011, p. 198.

- ^ Lennon 2014, p. 37.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 144, 190.

- ^ Frith & Horne 1987, p. 84.

- ^ Bowen 1999, quoted in Laing 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Lewisohn 2000, p. 27.

- ^ Lewisohn 2013, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Herriges 2010, p. 152.

- ^ Warner 2013, p. 159.

- ^ Gutterman 2014, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Gutterman 2014, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Gutterman 2014, p. 115.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 38.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, pp. 25, 55.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 55.

- ^ Simonelli 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Weber 2016, p. 31.

- ^ Everett 2001, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Frontani 2007, p. 106.

- ^ Gill 2004, p. 203.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 91.

- ^ Gendron 2002, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Doggett 2016, p. 327.

- ^ Reuters 1969, p. 5, quoted in Marquis 2020, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d Doggett 2005, p. 57.

- ^ a b Turner 2016, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Turner 2016, p. 30.

- ^ Pogrebin 2014.

- ^ a b Heylin 2021, p. 307.

- ^ Heylin 2021, p. 304.

- ^ Irwin 2008, p. 207.

- ^ Heylin 2021, pp. 302–305.

- ^ Heylin 2021, pp. 303–305.

- ^ Heylin 2021, p. 464.

- ^ Anon.(d) 2008.

- ^ Riley 2011, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Schaffner 1977, p. 41.

- ^ Ingham 2009, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Everett 2001, p. 406n48.

- ^ Howlett & Lewisohn 1990, p. 46.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 278n7.

- ^ Howlett & Lewisohn 1990, p. 50.

- ^ Doggett 2005, p. 284.

- ^ a b c d Doggett 2005, p. 93.

- ^ Miles 2007, p. 225.

- ^ a b Turner 2016, p. 355.

- ^ Turner 2016, pp. 355–356.

- ^ Turner 2016, p. 356.

- ^ Marwick 1993, pp. 568, 590n11.

- ^ Schaffner 1977, p. 215.

- ^ Marwick 1993, p. 568.

- ^ Hutton 1998, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c d e Rathjen 2012.

- ^ Lennon 1965.

- ^ Lennon 2010.

- ^ a b Scholl 2010.

- ^ Holzmann 2010.

- ^ Anon.(e) 2013.

- ^ Fernández 2013.

- ^ Lennon 2009.

- ^ Bogado 2013.

- ^ Robertson 2004, p. 162.

- ^ Doggett 2005, p. 66.

- ^ a b Isherwood 2008.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 173: late 1967, Kennedy and Spinetti; Everett 1999, p. 160: one-act play.

- ^ Lewisohn 2000, p. 266.

- ^ Davies 2012, p. 79.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 189: changed names; Doggett 2005, pp. 115–116, 132–133: late-1967 staging before changing names; Lennon 2014, pp. 38–40: "Scene three, Act one" a piece in In His Own Write.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 160.

- ^ Davies 2012, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Soloski 2008.

- ^ King 2001, p. 243.

- ^ Doggett 2005, p. 115.

- ^ Lewisohn 1988, p. 131.

- ^ a b Winn 2009, p. 139.

- ^ MacDonald 2007, p. 273.

- ^ Riley 2011, p. 399: Olivier produced; Winn 2009, p. 139: Spinetti directed.

- ^ Riley 2011, p. 733n6.

- ^ Riley 2011, pp. 399, 404.

- ^ Schaffner 1977, p. 113.

- ^ a b Howlett & Lewisohn 1990, p. 48.

- ^ Lewisohn 2000, p. 285.

- ^ a b Miles 2007, p. 266.

- ^ Schaffner 1977, p. 216.

- ^ Lennon, Kennedy & Spinetti 1968.

- ^ Norman 1981, p. 331, quoted in Everett 1999, p. 160.

- ^ a b Davies 2012, p. 138.

- ^ a b Riley 2011, p. 404.

- ^ Riley 2011, p. 404, 736n6.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 479.

- ^ Esslin 1968, p. 4D.

- ^ Sauceda 1983, p. 190.

- ^ a b Sauceda 1983, p. 189.

- ^ Lennon 2014, p. 55, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. 189.

- ^ Norman 1981, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. 189; Fawcett 1976, quoted in Sauceda 1983, p. 189.

- ^ a b Everett 1999, p. 162.

- ^ Lewisohn 2009, p. 156.

- ^ Harris 2004a, p. 330.

- ^ a b c Doggett 2011, p. 41.

- ^ Riley 2011, p. 395.

- ^ a b Spitz 2005, p. 773.

- ^ Hopkins 1987, p. 81, quoted in Everett 1999, p. 162.

- ^ Goodden 2017, pp. 211, 213.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 768.

- ^ Badman 2009, p. 431.

- ^ a b McVeigh 2015.

- ^ Awde 2015.

Sources

[edit]Books

[edit]- Badman, Keith (2009). The Beatles: Off the Record. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84772-101-3.

- Beatles, the (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8.

- Bowen, Phil (1999). A Gallery to Play to: The Story of the Mersey Poets. London: Stride. ISBN 1-900152-63-0.

- Carroll, Lewis (1871). Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. London: Macmillan & Co. OCLC 976600170.

- Clayson, Alan (2003). John Lennon. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 1-86074-487-7.

- Clayson, Alan (2003a). Ringo Starr. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 1-86074-488-5.

- Curley, Mallory (2005). Beatle Pete, Time Traveller. Randy Press. OCLC 62154854.

- Davies, Hunter (1968). The Beatles: The Authorized Biography. New York: Dell Publishing. OCLC 949339.

- Davies, Hunter, ed. (2012). The John Lennon Letters. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-20080-6.

- Doggett, Peter (2005). The Art and Music of John Lennon. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84449-954-0.

- Doggett, Peter (2011). You Never Give Me Your Money. New York: It Books. ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8.

- Doggett, Peter (2016). Electric Shock: From the Gramophone to the iPhone – 125 Years of Pop Music. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-957519-1.

- Epstein, Brian (1964). A Cellarful of Noise. New York: Doubleday. OCLC 617534.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through the Anthology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512941-0.

- Everett, Walter (2001). The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarry Men through Rubber Soul. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514105-4.

- Fawcett, Anthony (1976). John Lennon: One Day at a Time: A Personal Biography of the Seventies. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0-394-17920-X.

- Frith, Simon; Horne, Howard (1987). Art into Pop. New York: Methuen & Co. ISBN 978-0-415-04042-6.

- Frontani, Michael R. (2007). The Beatles: Image and the Media. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-966-8.

- Gendron, Bernard (2002). Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-Garde. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-28737-8.

- Goldman, Albert (1988). The Lives of John Lennon. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-04721-1.

- Goodden, Joe (2017). Riding So High: The Beatles and Drugs. London: Pepper & Pearl. ISBN 978-1-9998033-0-8.

- Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain, and America. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-307-35337-5.

- Gutterman, Scott (2014). John Lennon: The Collected Artwork. San Rafael: Insight Editions. ISBN 978-1-60887-029-5.

- Harry, Bill, ed. (1977). Mersey Beat: The Beginnings of the Beatles. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-86001-415-0.

- Hertsgaard, Mark (1995). A Day in the Life: The Music and Artistry of the Beatles. New York: Delacorte Press. ISBN 0-385-31377-2.

- Heylin, Clinton (2021). The Double Life of Bob Dylan: A Restless, Hungry Feeling, 1941–1966. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-53521-2.

- Hopkins, Jerry (1987). Yoko Ono. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-283-99521-1.

- Howlett, Kevin; Lewisohn, Mark (1990). In My Life: John Lennon Remembered. London: BBC Books. ISBN 0-563-36105-0.

- Howlett, Kevin (2017). Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band: 50th Anniversary Edition (Super Deluxe ed.) (booklet). Apple Records. 060255745530.

- Hutton, Margaret-Anne (1998). Countering the Culture: The Novels of Christiane Rochefort. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. ISBN 0-85989-585-8.

- Ingham, Chris (2009). The Rough Guide to the Beatles (3rd ed.). London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84836-525-4.

- Irwin, Colin (2008). Legendary Sessions: Bob Dylan: Highway 61 Revisited. New York: Billboard Books. ISBN 978-0-8230-8398-5.

- Joyce, James (1939). Finnegans Wake. London: Faber and Faber. OCLC 1193507470.

- Lennon, John (1965). In seiner eigenen Schreibe (in German and English). Translated by Kossodo, Helmut; Rogosky, Wolf Dieter. Geneva: Kossodo. OCLC 164709025.

- Lennon, John; Kennedy, Adrienne; Spinetti, Victor (1968). The Lennon Play: In His Own Write. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-20286-3.

- Lennon, John (2009). Por su propio cuento; Un españolito en obras (in Spanish and English). Translated by Ehrenhaus, Andy. Barcelona: Papel de Liar/Global Rhythm Press. ISBN 978-84-936679-7-9.

- Lennon, John (2010). In seiner eigenen Schreibe (in German and English). Translated by Kossodo, Helmut; Rogosky, Wolf Dieter; Bruckmaier, Karl. Berlin: Blumenbar Verlag. ISBN 978-3-936738-76-6.

- Lennon, John (2014) [1964]. In His Own Write (50th Anniversary ed.). Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-78211-540-3.

- Lewisohn, Mark (1988). The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0-600-63561-1.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2000). The Complete Beatles Chronicle: The Only Definitive Guide to the Beatles' Entire Career. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-60033-5.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2009). The Beatles' London: A Guide to 467 Beatles Sites In and Around London. Northampton: Interlink Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56656-747-3.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2013). The Beatles – All These Years, Volume One: Tune In. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-1-101-90329-2.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2013a). The Beatles – All These Years, Volume One: Tune In (Extended Special ed.). London: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-1-4087-0478-3.

- MacDonald, Ian (2007). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (Third ed.). Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-733-3.

- Marquis, Greg (2020). John Lennon, Yoko Ono and the Year Canada Was Cool. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company Ltd., Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4594-1541-6.

- Miles, Barry (1998). Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-5249-6.

- Miles, Barry (2007). The Beatles: A Diary – An Intimate Day by Day History. London: Omnibus. ISBN 978-1-84772-082-5.

- Norman, Philip (1981). Shout!: The True Story of the Beatles. London: Elm Tree. ISBN 0-241-10300-2.

- Norman, Philip (2008). John Lennon: The Life. New York: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-075401-3.

- Riley, Tim (2011). Lennon: The Man, the Myth, the Music—The Definitive Life. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-1-4013-2452-0.

- Sauceda, James (1983). The Literary Lennon: A Comedy of Letters: The First Study of All the Major and Minor Writings of John Lennon. Ann Arbor: Pierian Press. ISBN 0-87650-161-7.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1977). The Beatles Forever. Harrisburg: Cameron House. ISBN 0-8117-0225-1.

- Sheff, David (1981). Golson, G. Barry (ed.). The Playboy Interviews with John Lennon & Yoko Ono. New York: Berkley. ISBN 0-425-05989-8.

- Shotton, Pete; Schaffner, Nicholas (1983). John Lennon in My Life. Briarcliff Manor: Stein and Day. ISBN 0-8128-2916-6.

- Simonelli, David (2012). Working Class Heroes: Rock Music and British Society in the 1960s and 1970s. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-7053-3.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-80352-9.

- Weber, Erin Torkelson (2016). The Beatles and the Historians: An Analysis of Writings About the Fab Four. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-2470-9.

- Turner, Steve (2005). A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song (New and Updated ed.). New York: Dey St. ISBN 978-0-06-084409-7.

- Turner, Steve (2016). Beatles '66: The Revolutionary Year. New York: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-247558-9.

- Warner, Simon (2013). Text and Drugs and Rock 'n' Roll: the Beats and Rock Culture. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-7112-2.

- Watkins, Gwen (1983). Portrait of a Friend. Llandysul: Gomer Press. ISBN 0-85088-847-6.

- Wenner, Jann (1971). Lennon Remembers: The Rolling Stone Interviews. San Francisco: Straight Arrow. ISBN 0-87932-009-5.

- Winn, John C. (2008). Way Beyond Compare: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume One, 1957–1965. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45157-6.

- Winn, John C. (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.

- Womack, Kenneth (2014). Long and Winding Roads: The Evolving Artistry of the Beatles. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62892-515-9.

- Womack, Kenneth (2016). The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four (Abridged ed.). Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-4426-3.

- Womack, Kenneth (2017). Maximum Volume: The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin, The Early Years, 1926–1966. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61373-191-8.

Book chapters

[edit]- Burns, Gary (2009). "Beatles news: product line extensions and the rock canon". In Womack, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 217–229. ISBN 978-0-521-68976-2.

- Gill, Andy (2004). "Car Sick Blues". In Trynka, Paul (ed.). The Beatles: Ten Years that Shook the World. London: Dorling Kindersley. pp. 202–203. ISBN 0-7566-0670-5.

- Harris, John (2004). "Syntax Man". In Trynka, Paul (ed.). The Beatles: Ten Years that Shook the World. London: Dorling Kindersley. pp. 118–119. ISBN 0-7566-0670-5.

- Harris, John (2004a). "Cruel Britannia". In Trynka, Paul (ed.). The Beatles: Ten Years that Shook the World. London: Dorling Kindersley. pp. 326–331. ISBN 0-7566-0670-5.

- Herriges, Greg (2010). "In His Own Write, John Lennon (1964)". In Hemmer, Kurt (ed.). Encyclopedia of Beat Literature. New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-1-4381-0908-4.