Escape from L.A.

| Escape from L.A. | |

|---|---|

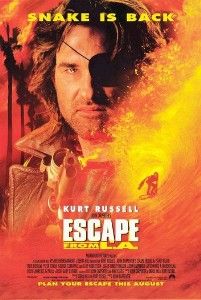

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Carpenter |

| Written by |

|

| Based on |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Gary B. Kibbe |

| Edited by | Edward A. Warschilka |

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 101 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English[1] |

| Budget | $50 million[3] |

| Box office | $42.3 million[4] |

Escape from L.A. (stylized on-screen as John Carpenter's Escape from L.A.) is a 1996 American post-apocalyptic action film co-written, co-scored, and directed by John Carpenter, co-written and produced by Debra Hill and Kurt Russell, with Russell also starring as Snake Plissken. A sequel to Escape from New York (1981), Escape from L.A. co-stars Steve Buscemi, Stacy Keach, Bruce Campbell, Peter Fonda, and Pam Grier. Escape from L.A. failed to meet the studio's expectations at the box office and received polarized reactions from critics.[5][6] The film later found a strong cult following.[7][8][9][10]

Plot

[edit]In 2000, a massive earthquake strikes the city of Los Angeles, cutting it off from the mainland as the San Fernando Valley floods. Declaring that God is punishing Los Angeles for its sins, a theocratic presidential candidate wins election to a lifetime term of office. He orders the United States capital relocated from Washington, D.C. to his hometown of Lynchburg, Virginia and enacts a series of strict morality laws, banning such things as smoking, alcohol, drugs, premarital sex, firearms, profanity, and red meat. Violators are given a choice between loss of U.S. citizenship and permanent deportation to the new Los Angeles Island, or repentance and death by electrocution. Escape from the island is made impossible due to a containment wall erected along the mainland shore and a heavy federal police presence monitoring the area.

By 2013, the U.S. has developed a superweapon known as the "Sword of Damocles," a satellite system capable of targeting electronic devices anywhere in the world and rendering them useless. The president intends to use it to dominate the world by destroying hostile nations' ability to function. His daughter Utopia steals the remote control for the system and escapes to Los Angeles Island in order to deliver it to Cuervo Jones, a Peruvian Shining Path revolutionary. Cuervo has marshaled an invasion force of third world nations and is planning to attack the U.S.

Facing deportation for a series of crimes, Snake Plissken is offered a chance to earn a pardon by traveling to the island and recovering the remote, a task that a previous rescue team failed to accomplish. To force his compliance, the president has one of his officers infect Snake with a virus that will kill him within ten hours and promises that he will receive the cure upon completing the mission. The president is not concerned with Utopia's safety, regarding her as a traitor.

Snake is issued equipment and sent to Los Angeles in a one-man submarine. As he explores the island, he meets "Map to the Stars" Eddie, a swindler who sells interactive tours and one of Cuervo's associates. Along the way, Snake is helped by Pipeline, a surfing enthusiast; Taslima, a woman deported for her Muslim faith; and Hershe Las Palmas (formerly Carjack Malone), a trans woman and past criminal associate of Snake's.

Eddie captures Snake and turns him over to Cuervo, who uses the Sword of Damocles to shut down Lynchburg in retaliation for Snake's presence. Cuervo threatens to inflict the same fate on the rest of the U.S. unless his demands are met. Snake escapes, and teams up with Hershe and her soldiers. The group travels by glider to the invasion staging area, at the "Happy Kingdom" in Anaheim. During a fight against Cuervo's troops, Snake takes the remote and Eddie alters one of the units he sells for his tours to match it. Snake, Eddie, Utopia, Hershe, and a group of Hershe's soldiers escape the island in a helicopter. Eddie shoots Cuervo, who fires a rocket launcher and hits the helicopter before dying. Hershe and her men are incinerated, Eddie jumps clear at liftoff, and Snake and Utopia do the same over the mainland and leave the helicopter to crash once Snake alerts the president to their approach.

At the crash site, the president and his officers find that both Snake and Utopia are carrying remotes and take the one held by Utopia (slipped into her pocket without her noticing), thinking that Snake has switched them. As Utopia is taken to the electric chair, Snake learns that the virus infecting him only causes a severe case of influenza that subsides within hours. The president tries to use Utopia's remote to neutralize an invasion force threatening Florida, but it only plays a recorded introduction to one of Eddie's tours.

Furious, the president orders his officers to kill Snake on the spot, but he proves to be only a hologram projected from a miniature camera that had been issued to him. Disgusted at the world's never-ending class warfare, he programs the real remote and triggers every satellite in the Sword of Damocles system, deactivating all technology on Earth and saving Utopia from electrocution as the power fails. Snake tosses the now-useless camera aside and lights a cigarette, then blows out the match and mutters, "Welcome to the human race."

Cast

[edit]- Kurt Russell as Lieutenant S.D. Bob "Snake" Plissken

- Steve Buscemi as "Map to the Stars" Eddie

- Peter Fonda as "Pipeline"

- Georges Corraface as Cuervo Jones

- Stacy Keach as Commander Mac Malloy

- Pam Grier as Hershe Las Palmas

- Cliff Robertson as President Adam

- Valeria Golino as Taslima

- Allison Joy Langer as Utopia

- Bruce Campbell as the Surgeon General of Beverly Hills

- Michelle Forbes as Lieutenant Brazen

- Ina Romeo as Hooker

- Peter Jason as Duty Sergeant

- Jordan Baker as Police Anchor

- Caroleen Feeney as Woman On Freeway

- Paul Bartel as Congressman

- Tom McNulty as Officer

- Jeff Imada as "Mojo" Dellasandro, Saigon Shadow

- Breckin Meyer as Surfer

- Robert Carradine as Skinhead

- Leland Orser as "Test Tube"

- Shelly Desai as Cloaked Figure

Production

[edit]Escape from L.A. was in development for over 10 years. In 1987, screenwriter Coleman Luck was commissioned to write a screenplay for the film with Dino De Laurentiis's company producing, which John Carpenter later described as being "too light, too campy".[11] Carpenter stated one of the reasons it took so long to develop a sequel was because of his negative views on sequels, especially in regards to the ones that followed on from Halloween.[12]

Eventually, Carpenter and Kurt Russell got together to write with their long-time collaborator Debra Hill with Russell instigating the process as he took inspiration from contemporary events in Los Angeles such as the 1994 Northridge earthquake and the 1992 Los Angeles riots.[12][13] Carpenter insists that Russell's persistence allowed the film to be made, since "Snake Plissken was a character he loved and wanted to play again." Carpenter credited that same enthusiasm with motivating Russell's work on the script, declaring "I used his passion to do the movie to get him to write more".[14]

Filming

[edit]Carpenter has described Escape from L.A. as both "fun to make" and requiring "months of nights" of work.[15] Carpenter would later recall that the theme park scene, shot at night on a Universal backlot, resulted in a noise complaint from Rick Dees which forced them to cease using live ammunition.[16] CG supervisor David Jones has expressed his distaste for the resulting effects used in the battle, which he described as "a little iffy".[17] Although uncredited, Tony Hawk has claimed that he and fellow professional skateboarder Chris Miller worked as stunt doubles for Peter Fonda and Kurt Russell during the surfing scene.[18] Several scenes were shot in Carson, including the Sunset Boulevard and freeway sequences.[19] The Sunset Boulevard scene was filmed in a landfill, where production staff constructed over 120 structures to create a shanty town. To create the impression of a crowded post-apocalyptic freeway, 250 broken cars were sourced from a junkyard in Ventura.[19]

Music

[edit]Soundtrack

[edit]| Escape from L.A. | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by various artists | |

| Released | July 16, 1996 |

| Genre | Alternative metal,[20] industrial rock[20] |

| Label | Lava/Atlantic |

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

- "Dawn" – Stabbing Westward

- "Sweat" – Tool

- "The One" – White Zombie

- "Cut Me Out" – Toadies

- "Pottery" – Butthole Surfers

- "10 Seconds Down" – Sugar Ray

- "Blame (L.A. Remix)" – Gravity Kills

- "Professional Widow" – Tori Amos

- "Paisley" – Ministry

- "Fire in the Hole" – Orange 9mm

- "Escape from the Prison Planet" – Clutch

- "Et Tu Brute?" – CIV

- "Foot on the Gas" – Sexpod

- "Can't Even Breathe" – Deftones

Score

[edit]The film's score has been released twice, the first on both CD and cassette by Milan Records in 1996 and again as an expanded CD release by specialty label La-La Land Records in 2014 that featured pieces of music that were recorded for but ultimately cut from the film.[21]

Release

[edit]Home media

[edit]Escape from L.A. was initially released on DVD in the United States on December 15, 1998, and later reissued on September 26, 2017.[22]

The film was released on Blu-ray by Paramount on May 4, 2010.[23] In 2020, Shout! Factory released a new 4K restoration on Blu-ray.[24] In 2022, the 4K restoration was released on 4K Blu-ray. Upon its release, an English audio encoding error was noted by several reviewers, prompting Paramount to correct the issue in unreleased discs and launch a replacement program for initial purchasers.[25]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Escape from L.A. grossed $25,477,365 in the United States and Canada from its $50 million budget, about as much as its predecessor but little more than half its significantly higher budget.[26] Internationally it grossed $16.8 million for a worldwide total of $42.3 million.[4]

Critical response

[edit]The film received mixed reviews and has a 53% approval rating from Rotten Tomatoes based on 57 reviews, with an average score of 5.6/10. The site's consensus reads: "Escape from L.A. has its moments, although it certainly suffers in comparison to the cult classic that preceded it".[27] Roger Ebert gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of a possible four and wrote that the movie felt it was an attempt to satirize the genre while exploiting it: "[Escape from L.A.] has such manic energy, such a weird, cockeyed vision, that it may work on some moviegoers as satire and on others as the real thing."[28]

Todd McCarthy of Variety wrote, "A cartoonish, cheesy, and surprisingly campy apocalyptic actioner, John Carpenter's Escape From L.A. is spiked with a number of funny and anarchic ideas, but doesn't begin to pull them together into a coherent whole."[29] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly rated it C+ and wrote, "Carpenter never was the filmmaker his cult claimed him to be, but in Escape From L.A., he at least has the instinct to keep his hero moving, like some leather-biker Candide."[30] Stephen Holden of The New York Times wrote that the film's in-jokes "go a long way toward keeping afloat a hopelessly choppy adventure spoof that doesn't even to try to match the ghoulish surrealism of its forerunner."[31]

Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "With much humor and high adventure, John Carpenter's Escape From L.A. brilliantly imagines a Dante-esque vision of the City of Angels."[32] Peter Stack of The San Francisco Chronicle rated it 3/4 stars and called it "dark, percussive and perversely fun."[33] Esther Iverem of The Washington Post wrote that the film "tries but fails to be an action-hero flick or even a parody of one."[34] Marc Savlov of The Austin Chronicle rated it 3/5 stars and wrote, "Loud, rollicking, alternately ultraviolent and hilarious, Escape from L.A. is Snake redux, and what more do you need, really?"[35] Nigel Floyd of Time Out London wrote, "After 15 years of computer-generated effects, apocalyptic sci-fi and Arnie movies with flippant kiss-off lines, the sequel feels hackneyed and pointless."[36] Kim Newman of Empire rated it 2/5 stars and wrote, "Apart from a few good characters, this is really not up to scratch in most departments especially the ludicrous plot."[37]

In a 2013 retrospective, Alan Zilberman of The Atlantic called Snake Plissken "a pro-nostalgia antihero, disgusted by the world around him." While contrasting the film's then-futuristic plot elements against modern-day reality, Zilberman writes that the film's ending is more profound today, as Plissken would be annoyed by our fascination with technology, citing the example of two friends who ignore each other while transfixed with their smart phones.[38]

John Carpenter later reflected:

Escape from L.A. is better than the first movie. Ten times better. It's got more to it. It's more mature. It's got a lot more to it. I think some people didn't like it because they felt it was a remake, not a sequel... I suppose it's the old question of whether you like Rio Bravo or El Dorado better? They're essentially the same movie. They both had their strengths and weaknesses. I don't know–you never know why a movie's going to make it or not. People didn't want to see Escape that time, but they really didn't want to see The Thing... You just wait. You've got to give me a little while. People will say, you know, what was wrong with me?[39]

He reiterated his statement in another interview: "It is a better movie. It didn't do what the first one did for some reason. Maybe it was too dark, too nihilistic. I don't know. They didn't dig it as much as the first one. It did okay, but it just wasn't a hit."[40]

About the cult following, Carpenter said: "I'm just delighted that it's gaining that popularity. I really dig Escape from L.A., and I always have."[10]

Other media

[edit]Escape from Earth

[edit]A sequel of the movie, titled Escape from Earth, was meant to be produced after Escape from L.A. but the underperformance of the latter changed the plans. According to John Carpenter, Escape from Earth would have picked up with Snake Plissken right after the ending of Escape from L.A., which saw him activating a superweapon known as the Sword of Damocles: "Escape from Earth was kind of Snake Plissken in a space capsule, flying interstellar. So there'd be a lot of special effects in it. Which I never care about too much. But that's what it would look like."[41]

Comic books

[edit]Marvel Comics released the one-shot The Adventures of Snake Plissken in January 1997.[42] The story takes place sometime between Escape from New York and his famous Cleveland escape mentioned in Escape from L.A.. Snake has robbed Atlanta's Centers for Disease Control of some engineered metaviruses and is looking for buyers in Chicago. Finding himself in a deal that's really a set-up, he makes his getaway and exacts revenge on the buyer for ratting him out to the United States Police Force. In the meantime, a government lab has built a robot called ATACS (Autonomous Tracking And Combat System) that can catch criminals by imprinting their personalities upon its program in order to predict and anticipate a specific criminal's every move. The robot's first test subject is Snake. After a brief battle, ATACS copies Snake to the point of fully becoming his personality. Now recognizing the government as the enemy, ATACS sides with Snake. Snake punches the machine and destroys it, reasoning, "I don't need the competition."

Cancelled video game

[edit]An Escape from L.A. video game was announced for the Sega Saturn, Sony PlayStation, Panasonic M2, and PC in 1996,[43] but was later cancelled.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Escape from L.A.". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ^ Spelling, Ian (July 19, 1996). "Now Director John Carpenter 'Escapes From L.a.'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ "Escape from L.A." The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ a b "Top 100 worldwide b.o. champs". Variety. January 20, 1997. p. 14.

- ^ Escape from L.A., archived from the original on December 15, 2019, retrieved February 26, 2022

- ^ "John Carpenter's other, sillier Escape". Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ "Why Escape From LA Is Good, Actually". Collider. July 21, 2021. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "John Carpenter's Escape from L.A. Is underrated, as satire and as pulp". The A.V. Club. May 5, 2016. Archived from the original on February 1, 2022. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ "'Escape from L.A.': Reassessing John Carpenter's futuristic '90s flop". NME. February 24, 2022. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ a b "John Carpenter Talks Cult Classic 'Escape from L.A.' and Being Open to Directing Again". Forbes. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Gilles Boulenger, John Carpenter Prince of Darkness, (Los Angeles, Silman-James Press, 2003), pp.246, ISBN 1-879505-67-3

- ^ a b Beeler, Michael (August 1996). "Escape from L.A." Cinefantastique. Fourth Castle Micromedia. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 9, 1996). "Escape From L.A. movie review (1996) | Roger Ebert". Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Bennett, Tara (February 24, 2022). "Escape From L.A.: John Carpenter on Snake's Return, Surfing Tsunamis, and Escaping From Earth". IGN. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ "'Escape From L.A.': reassessing John Carpenter's futuristic '90s flop". NME. February 24, 2022. Archived from the original on February 24, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- ^ "Escape From L.A. Director John Carpenter Looks Back at the Cult-Hit Action Film". Horror. Archived from the original on March 15, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ FranchiseFredOfficial (June 14, 2020). "'Escape From L.A.' Filmmaker Reveals Why the Kurt Russell Surfing Scene Looks So Cheesy". Showbiz Cheat Sheet. Archived from the original on January 29, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- ^ @tonyhawk (January 5, 2017). "Had no idea when Chris Miller & I got asked to stunt double Kurt Russell & Peter Fonda that we'd be in cinematic gold: Escape From LA (1996)" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Calhoun, John (October 1996). "Designer sketchbook: Escape from LA". Entertainment Design: 78. ProQuest 209633416.

- ^ a b c Ankeny, Jason. "Escape from L.A. [Original Film Soundtrack] - Various Artists" Archived December 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Allmusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ^ "Escape from L.A. [Original Score] - John Carpenter, Shirley Walker Releases". allmusic.com. Rovi. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ "Escape from L.A. DVD Release Date". DVDs Release Dates. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Tyner, Adam (May 4, 2010). "Escape from L.A. (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ "Escape from L.A. Blu-ray (Collector's Edition)". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Escape from L.A. - 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray Ultra HD Review | High Def Digest". ultrahd.highdefdigest.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Escape from L.A.". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "John Carpenter's Escape from L.A. (1996)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 9, 1996). "Escape from L.A. >> Reviews". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (August 12, 1996). "Review: 'John Carpenter's Escape from L.A.'". Variety. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (August 23, 1996). "Escape From L.A." Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 24, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (August 9, 1996). "Escape From L.A." The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (August 9, 1996). "This Makes SigAlerts Seem Tame". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Stack, Peter (August 9, 1996). "FILM REVIEW -- The Ocean Falls into L.A. / Drowned city stars with Kurt Russell in "Escape' sequel". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Iverem, Esther (August 9, 1996). "'Escape From L.A.': Doom & Dumber". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Savlov, Marc (August 9, 1996). "John Carpenter's Escape From L.A." The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Floyd, Nigel (September 10, 2012). "John Carpenter's Escape from L.A." Time Out London. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Newman, Kim. "Escape From LA". Empire. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Zilberman, Alan (August 8, 2013). "Escape From L.A., Today: How a 1996 Sci-Fi Thriller Imagined the Year 2013". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ ""It's Always the Story" - The Craft of Carpenter". creativescreenwriting.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ "John Carpenter interview". Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ "John Carpenter Discusses Escape from New York Threequel, Backs Wyatt Russell as Snake Plissken". February 22, 2022. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ "The Adventures of Snake Plissken #1 (Marvel)". Comicbookrealm.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "Celebrity Sightings". GamePro. No. 92. IDG. May 1996. p. 21.

External links

[edit]- 1996 films

- 1996 independent films

- 1990s dystopian films

- 1990s satirical films

- 1990s science fiction action films

- American independent films

- American satirical films

- American science fiction action films

- American sequel films

- American dystopian films

- American post-apocalyptic films

- Urban survival films

- Films directed by John Carpenter

- Films produced by Debra Hill

- Films set in 2000

- Films set in 2013

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set in the future

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films shot in Texas

- Films shot in New Braunfels, Texas

- Films about fictional presidents of the United States

- Films set in Orange County, California

- Films with screenplays by John Carpenter

- Films with screenplays by Debra Hill

- Films scored by Shirley Walker

- Films scored by John Carpenter

- Rysher Entertainment films

- Paramount Pictures films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s American films

- 1996 science fiction films

- English-language science fiction action films

- English-language independent films