The Man Who Knew Too Much (Alexander McQueen collection)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (Autumn/Winter 2005) is the twenty-sixth collection by British designer Alexander McQueen for his eponymous fashion house. It took inspiration from the fashion of the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the films of Alfred Hitchcock; its namesake is Hitchcock's The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956). The runway show was staged during Paris Fashion Week on 4 March 2005 at the Lycée Carnot, a secondary school in Paris. Forty-eight looks were presented; the first thirty-six were daywear, while the final twelve were eveningwear. The collection's clothing and runway show both lacked McQueen's signature theatricality, and critical reception at launch and in retrospect was negative. It was the debut of the Novak handbag, which became a best-seller for the brand. Critical analysis has examined why McQueen pivoted to a more commercial approach, as well as the influence of film on the collection.

Background

[edit]British fashion designer Alexander McQueen was known for his imaginative, sometimes controversial designs.[1][2][3] During his nearly twenty-year career, he explored a broad range of ideas and themes, including historicism, romanticism, femininity, sexuality, and death.[1][2][3] McQueen began his career in fashion as an apprentice on Savile Row, which earned him a reputation as an expert tailor.[4][5][6] His fashion shows were known for being theatrical to the point of verging on performance art.[7][8] Sarah Burton, his assistant during much of his career, later said that he "just didn't like doing normal catwalk shows".[9]

McQueen's personal fixations and interests were a throughline in his career, and he returned to certain ideas and visual motifs repeatedly.[10][11] His collections were historicist, in that he adapted historical designs and narratives, and self-referential, in that he revisited and reworked ideas between collections.[12] As a cinemaphile, he drew on his favorite films to inspire his collections.[13] He was fond of Alfred Hitchcock, whose film The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) was one of McQueen's childhood favorites.[14] One of McQueen's earliest collections, The Birds (Spring/Summer 1995), was named for Hitchcock's 1963 film The Birds.[15] Although that collection's tight pencil skirts and wasp-waisted jackets were a reference to the tightly tailored outfits worn by the film's star, Tippi Hedren, McQueen avoided directly copying her wardrobe.[15][16][17]

Concept and collection

[edit]

The Man Who Knew Too Much (Autumn/Winter 2005) is the twenty-sixth collection by British designer Alexander McQueen for his eponymous fashion house. It was inspired by the fashion of the 1950s and 1960s, particularly as seen in Alfred Hitchcock thrillers like its namesake film The Man Who Knew Too Much.[14][18][19] With jeans, leather, and leopard print, it also drew on classic rock and roll and biker fashion.[19][20] Author Judith Watt also suggested some inspiration from the Pearly Kings and Queens of London, known for their distinctive suits covered in mother-of-pearl buttons.[21][22]

Unusually for McQueen, the collection was straightforward and conventional.[23][14] The palette was muted, with a focus on taupe, grey, and black, with pops of colour.[24] The designs emphasised the female form in an old-fashioned way, with tailoring and knitwear that hugged the body, rather than relying on cuts which exposed the breasts and buttocks the way his earliest designs had.[19][25] The restrained aesthetic referenced the image of the "Hitchcock blonde", a stereotype of the attractive but sexually reserved women who led Hitchcock's films.[26][17]

The daywear portion mainly featured tailored tweed suits with pencil skirts, cocktail dresses, and knitwear in sixties mohair and Fair Isle styles. shown with slim-fit trousers and jeans with cuffs. For outerwear, there were trench coats, leather jackets, and sweaters and wrap jackets influenced by Peruvian textiles and Navajo weaving.[14][21][27] Look 22, a jacket, top, and pencil skirt in wool bouclé and cashmere, is a clear homage to Tippi Hedren's outfit from The Birds, a reference McQueen had deliberately avoided making in the earlier eponymous collection.[28]

The eveningwear portion comprised 1950s-inspired ball gowns, including a red one with a voluminous mermaid skirt that evoked the designs of Charles James.[14][23][21] The dress which closed the collection was a take on the bejewelled, flesh-toned, and skintight dress worn by actress Marilyn Monroe when she sang "Happy Birthday" to President John F. Kennedy in 1963.[21]

Ensembles were rendered with feminine 1950s details and accessories like sunglasses, pearl jewellery, leather gloves, handbags, seamed stockings, and matching shoes.[14][23][24] The collection featured the first Alexander McQueen handbag, called the "Novak". It was named for actress Kim Novak, who frequently appeared in Hitchcock films.[14]

Runway show

[edit]

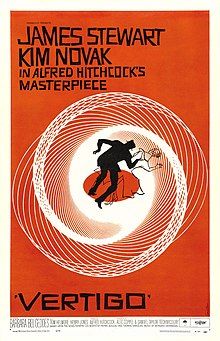

The runway show was staged during Paris Fashion Week on 4 March 2005 at the Lycée Carnot, a public secondary school, in Paris.[29] The invitation for the show was a poster based on the theatrical poster for Hitchcock's 1958 film Vertigo.[14][17] The soundtrack comprised selections from the 1950s and 1960s, including songs from Johnny Kidd & the Pirates, Alan Vega, Dusty Springfield, Elvis Presley, and Martha and the Vandellas.[14]

The show was produced by Gainsbury & Whiting.[29] Joseph Bennett, who had designed all of McQueen's runways since No. 13 (Spring/Summer 1999), returned for set design.[30] Katy England took care of overall styling, Guido Palau was responsible for hair, and Peter Philips handled makeup.[29]

McQueen's usual theatrical flair was absent from the runway show; his right-hand woman, Sarah Burton, recalled it as "the nearest he came to a standard runway presentation".[9] The unadorned catwalk ran straight down the centre of the school's central hall, with the audience seated around it.[31] The show opened with orange-red overhead lights illuminating the runway. White spotlights flashed one by one on the upper balcony, finally illuminating a pair of doors through which the models entered. They circled the balcony, eventually descending stairs at the other end to reach the runway.[27] The windows at the rear of the room were backlit in purple.[14] Curator Kate Bethune felt this backdrop was influenced by Hitchcock's Rear Window (1954), in which a man watches his neighbours through their windows.[14]

Forty-eight looks were presented; the first thirty-six were daywear, while the final twelve were eveningwear.[19][23] Models were styled with bouffant hair in the mode of the 1950s and 60s.[14][23] Makeup was restrained, mainly consisting of matte lips and black flicked eyeliner.[23][19] Model Hannelore Knuts walked with backcombed bleach-blonde hair, red lipstick, and a false beauty mark, recalling the iconic style of Marilyn Monroe.[24] Julia Stegner wore tousled hair that evoked a look actress Brigitte Bardot was known for.[14]

After the final look, the lights went down briefly, before coming back up to show the models taking their final turn, with two in evening gowns posing on the stairs to the back of the runway. McQueen did not come out on the runway for a bow, and left the show without greeting the attendees.[32][33]

Reception

[edit]Critics complained that McQueen had become "safe and commercial".[32] Despite the negative reviews, The Guardian reported that the designs "had buyers and [magazine] editors alike salivating".[34] Despite the negative critical reaction, the collection was reportedly a sales success for McQueen.[34][14] McQueen defended his more commercial approach as the result of greater confidence in his designs: "You can hide so much more behind theatrics, and I don’t need to do that anymore."[34]

Writing for Vogue, Sarah Mower was disappointed that the collection mainly showcased safe ideas McQueen had explored before, although she felt the results were solid. She thought the runway show was repetitive and cynical, calling it "a merchandise run-through of dubious taste".[19]

The collection is viewed with little enthusiasm in retrospect. In her 2012 biography of McQueen, Judith Watt wrote that Look 39, a red ball gown, was "like a Charles James [design] but not as good".[21] She felt that McQueen's immediate departure after the show was an indication that he was under great stress at the time.[21] In her 2015 book Gods and Kings, Dana Thomas called it a "soulless exercise" indicative of McQueen's late-career malaise, and mentioned it only to opine that it was a "far more literal" interpretation of Hitchcock than The Birds had been.[35] Andrew Wilson, in his 2015 biography of McQueen Blood Beneath the Skin, called it "elegant", but otherwise spent little time on it.[18] No items from the collection appeared in Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, a retrospective exhibition that covered McQueen's entire career.[36]

Some authors have been more positive about the collection in hindsight. Author Katherine Gleason described it as "contemporary vision of wearable glamour".[27] Curator Claire Wilcox found the collection "upbeat and commercial", and felt that it showcased McQueen's versatility in genre.[23] Judith Watt and Kate Bethune both noted the irony that a designer who had taken years of criticism for relying too heavily on theatrics at the expense of the clothing had been criticised for producing a low-key collection focused solely on the designs.[14][21]

Analysis

[edit]Authors have offered a number of rationales for the collection's lack of theatrics. Watt suggested that McQueen may have felt pressured to rely on safe, saleable designs in order to satisfy the management at Gucci, which owned 51 per cent of the McQueen label.[21][37] Gleason suggested the rising economic influence of teens may have prompted McQueen to include youth-friendly garments like patterned sweaters and cropped jeans.[24] Watt speculated that the straightforward design of the Fair Isle sweaters may have been intended as a lead-in for McQ, the brand's upcoming diffusion line.[21]

Film theorist Alistair O'Neill focused on the collection as it related to Hitchcock. McQueen referenced several of the director's films throughout his career, exploring what O'Neill called "representations of femininity and how they are challenged through transformation scenes".[38] O'Neill thought the collection "distilled the Hitchcock blonde" across many looks, rewarding repeat viewing in a manner akin to film.[17] He considered McQueen's interpretation of Hedren's ensemble to be "more faithful" to the costume designer's original sketch than what appeared in the film, labelling it "a doppelgänger".[17]

Legacy

[edit]Several looks from The Man Who Knew Too Much have been photographed for editorials in Vogue. Paolo Roversi photographed Look 8, a black minidress with lace back, and Look 48, the beaded finale dress, for the December 2005 issue, in a shoot McQueen styled himself.[39] Regan Cameron photographed Cate Blanchett in the red ball gown from Look 39.[40] Patrick Demarchelier photographed Look 38, a black floor-length dress with white tulle underskirt.[41] Carter Smith also photographed Look 48 for a different shoot, accessorizing it with a cropped tweed jacket.[39]

The Novak bag became a trendy accessory for celebrities. As the brand's primary handbag, it was reissued in several sizes, colours, and fabrics over several years.[42][24]

McQueen's friend Alice Smith auctioned a collection of McQueen memorabilia in 2020; an invitation from The Man Who Knew Too Much sold for $2,440.[43] Trino Verkade, McQueen's first employee, auctioned her archive in 2014, including four items from The Man Who Knew Too Much.[44][45] One silver cocktail dress, Look 43 on the runway, that went for £2,200.[46]

Bibliography

[edit]- Alexander McQueen | Women's Autumn/Winter 2005 | Runway Show. Alexander McQueen. 15 March 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2024 – via YouTube.

- Bolton, Andrew (2011). Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty. New York City: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-412-5. OCLC 687693871.

- Frankel, Susannah (2011). "Introduction". In Bolton, Andrew (ed.). Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty. New York City: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 17–27. ISBN 978-1-58839-412-5.

- Callahan, Maureen (2014). Champagne Supernovas: Kate Moss, Marc Jacobs, Alexander McQueen, and the '90s Renegades Who Remade Fashion. New York City: Touchstone Books. ISBN 978-1-4516-4053-3.

- Cohan, Steve (1997). Masked Men: Masculinity and the Movies in the Fifties. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-11587-4.

- Esguerra, Clarissa M.; Hansen, Michaela (2022). Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mythos, Muse. New York City: Delmonico Books. ISBN 1-63681-018-7. OCLC 1289986708.

- Fairer, Robert; Wilcox, Claire (2016). Alexander McQueen: Unseen. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-22267-X. OCLC 946216643.

- Fox, Chloe (2012). Vogue On: Alexander McQueen. Vogue on Designers. London: Quadrille Publishing. ISBN 1849491135. OCLC 828766756.

- Gleason, Katherine (2012). Alexander McQueen: Evolution. New York City: Race Point Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61058-837-9. OCLC 783147416.

- Homer, Karen (2023). Little Book of Alexander McQueen: The Story of the Iconic Brand. London: Welbeck Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-80279-270-6.

- Honigman, Ana Finel (2021). What Alexander McQueen Can Teach You About Fashion. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-5906-5.

- Knox, Kristin (2010). Alexander McQueen: Genius of a Generation. London: A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-3223-4. OCLC 794296806.

- Mora, Juliana Luna; Berry, Jess (2 September 2022). "Creative Direction Succession in Luxury Fashion: The Illusion of Immortality at Chanel and Alexander McQueen". Luxury. 9 (2–3): 126, 128, 132. doi:10.1080/20511817.2022.2194039. ISSN 2051-1817.

- Thomas, Dana (2015). Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano. New York City: Penguin Publishing. ISBN 978-1-101-61795-3. OCLC 951153602.

- Watt, Judith (2012). Alexander McQueen: The Life and the Legacy. New York City: Harper Design. ISBN 978-1-84796-085-6. OCLC 892706946.

- Wilcox, Claire, ed. (2015). Alexander McQueen. New York City: Abrams Books. ISBN 978-1-4197-1723-9. OCLC 891618596.

- Bethune, Kate. "Encyclopedia of Collections". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 303–326.

- O'Neill, Alistair. "The Shining and Chic". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 261–280.

- Wilson, Andrew (2015). Alexander McQueen: Blood Beneath the Skin. New York City: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-7674-3. OCLC 1310585849.

- Young, Caroline; Martin, Ann (2017). Tartan + Tweed. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. ISBN 978-0-7112-3822-0. OCLC 947020251.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Frankel 2011, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b "Alexander McQueen – an introduction". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ a b Mora & Berry 2022, pp. 126, 128, 132.

- ^ Doig, Stephen (30 January 2023). "How Alexander McQueen changed the world of fashion – by the people who knew him best". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023.

- ^ Carwell, Nick (26 May 2016). "Savile Row's best tailors: Alexander McQueen". GQ. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Vaidyanathan, Rajini (12 February 2010). "Six ways Alexander McQueen changed fashion". BBC Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 February 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Gleason 2012, p. 10.

- ^ Fairer & Wilcox 2016, p. 13.

- ^ a b Bolton 2011, p. 227.

- ^ "Alexander McQueen – an introduction". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Watt 2012, p. 148.

- ^ "Alexander McQueen – an introduction". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Manning, Emily (21 January 2016). "An Alexander McQueen biopic is in the works". i-D. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Bethune 2015, p. 316.

- ^ a b Callahan 2014, p. 103.

- ^ Thomas 2015, p. 123.

- ^ a b c d e O'Neill 2015, p. 274.

- ^ a b Wilson 2015, p. 298.

- ^ a b c d e f Mower, Sarah (4 March 2005). "Alexander McQueen Fall 2005 Ready-to-Wear Collection". Vogue. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Gleason 2012, pp. 135, 137.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Watt 2012, p. 224.

- ^ Howard, Ellie. "The pearly kings and queens: London's 'other' royal family". BBC Travel. Archived from the original on 2023-04-16. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fairer & Wilcox 2016, p. 200.

- ^ a b c d e Gleason 2012, p. 137.

- ^ Young & Martin 2017, p. 146.

- ^ Cohan 1997, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Gleason 2012, p. 135.

- ^ O'Neill 2015, pp. 274–276.

- ^ a b c Fairer & Wilcox 2016, p. 344.

- ^ "Interview: Joseph Bennett on Lee McQueen". SHOWstudio. 16 March 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Alexander McQueen 2012, 00:12.

- ^ a b Gleason 2012, p. 138.

- ^ Alexander McQueen 2012, 12:26.

- ^ a b c Cartner-Morley, Jess (19 September 2005). "Boy done good". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Thomas 2015, p. 333.

- ^ Bolton 2011, pp. 232–235.

- ^ "Obituary: Fashion king Alexander McQueen". BBC. 11 February 2010. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ O'Neill 2015, p. 273.

- ^ a b Fox 2012, pp. 99–102, 159.

- ^ Fox 2012, pp. 93–94, 159.

- ^ Fox 2012, pp. 23–24, 159.

- ^ Knox 2010, p. 66.

- ^ "Alexander McQueen: The Man Who Knew Too Much invitation". RR Auction. 15 September 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ Bromley, Joe (11 June 2024). "'I spent my life helping Alexander McQueen. Now I'm selling my rare archive'". Evening Standard. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ "Passion for Fashion: the Trino Verkade Collection". Kerry Taylor Auctions. 11 June 2024. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- ^ "Lot 96 – An Alexander McQueen silver cocktail dress, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Autumn-Winter 2005-06". Kerry Taylor Auctions. 11 June 2024. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

External links

[edit]- Alexander McQueen | Women's Autumn/Winter 2005 | Runway Show. Alexander McQueen. 15 March 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2024 – via YouTube.