The Mackintosh Man

| The Mackintosh Man | |

|---|---|

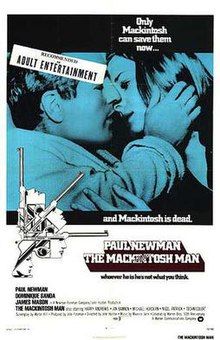

Original film poster by Tom Chantrell | |

| Directed by | John Huston |

| Screenplay by | Walter Hill |

| Based on | The Freedom Trap by Desmond Bagley |

| Produced by | John Foreman |

| Starring | Paul Newman Dominique Sanda James Mason Harry Andrews Ian Bannen |

| Cinematography | Oswald Morris |

| Edited by | Russell Lloyd |

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

Production company | Newman-Foreman Company |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. (US) Columbia-Warner Distributors (UK) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 99 minutes |

| Countries | United States[2]

United Kingdom[3] |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1,500,000 (US/ Canada rentals)[4] |

The Mackintosh Man is a 1973 Cold War spy film directed by John Huston from a screenplay by Walter Hill, based on the novel The Freedom Trap by English author Desmond Bagley.[5] Paul Newman stars as Joseph Rearden, a jewel thief-turned-intelligence operative, sent to infiltrate a Soviet spy ring in England, by helping one of their agents break out of prison. The cast also features Dominique Sanda, James Mason, Harry Andrews, Michael Hordern and Ian Bannen.

Filmed in England, Malta, and the Republic of Ireland, The Mackintosh Man was released in the United States by Warner Bros. on July 25, 1973, where it received a mixed critical response.[6] Huston called it "a spy thriller with some amusing moments" that was similar to his earlier The Kremlin Letter.[7]

Plot

[edit]Joseph Rearden, a petty criminal-turned-agent for British intelligence, arrives in London. There, MI5 officer Mackintosh and his deputy, Mrs. Smith, inform Rearden of a way to steal diamonds which are transported via the postal service. This he does, punching a postman in the process. That evening, however, two detectives visit Rearden's hotel room.

At his trial, the judge is angered by the failure to recover the stolen diamonds and sentences Rearden to 20 years in jail.[a] There, He slowly begins to blend in with the other prisoners, and is assigned to laundry-washing duties. Days after entering, he encounters Ronald Slade, a former intelligence officer kept in high security after having been exposed as a KGB mole. He makes innocent enquiries of his fellow inmates about Slade, but not a great deal is known about him.

Weeks later, he is approached by an inmate mentioning an organisation which can spring him from prison in exchange for a cut of the diamonds. Rearden agrees. Two days later, a diversion is arranged, and smoke bombs are hurled over the walls. Rearden and a fellow prisoner, who turns out to be Slade, are then lifted by a cargo net and driven away. They are then drugged and taken to a secret location, somewhere in wild, deserted countryside. After awaking, Rearden and Slade are told that they will be kept there for a week until the hunt for them dies down.

In London, Mackintosh monitors Rearden's progress. Rearden's entry into prison has been a planned sting operation to smoke out the organisation. In the House of Commons, an old friend and war comrade, Sir George Wheeler MP, gives a speech attacking the handling of the Slade escape. Mackintosh later approaches Wheeler and advises him that it would be better to remain silent or risk embarrassing himself. Wheeler, however, despite masquerading as a patriotic right-winger, is actually a Communist agent of the KGB. He tips off the head of the organisation where Rearden is being held. Mackintosh had suspected Wheeler and had used their meeting to try to flush him out. Before Mackintosh can act, he is run down by a car and dies.

Meanwhile, Rearden falls under suspicion by the escape organisation. Doubting his claims to be an Australian criminal, they beat him and attack him with a guard dog. He fights back and escapes the building, setting it on fire. Outside, he is still pursued by his guards and the dog. Rearden is eventually forced to drown the dog in a stream to throw his assailants off the scent. He then reaches a nearby town and discovers that he is on the west coast of Ireland. He has apparently been staying on the estate of a close friend of Wheeler. Rearden contacts Mrs Smith, who flies to meet him in Galway. Realising that Slade has been smuggled out of Ireland on Wheeler's private yacht, they now head to Valletta, Malta, where Wheeler is heading.

In Malta, they try to infiltrate one of Wheeler's parties and discover Slade's whereabouts. Wheeler recognises Mrs Smith — Mackintosh's daughter — drugs her, and takes her aboard his yacht. Rearden tries to get the Maltese police to raid the boat, but they refuse to believe that Wheeler, a respected man, can be involved in kidnapping and treason. Instead, they move to arrest Rearden, who is still a wanted man. Forced to flee, Rearden follows Wheeler to a church where he and Slade are holding Mrs Smith. Pulling a gun on them, Rearden orders them to hand over Mrs Smith. Wheeler and Slade try to persuade Rearden to let them go unharmed, in return for which they will also spare him and Mrs Smith. Reluctantly Rearden agrees, but Mrs Smith takes up a gun and shoots Slade and Wheeler, avenging Mackintosh's murder. She then abandons Rearden, angry at the way he has not followed his own orders.

Cast

[edit]- Paul Newman as Joseph Rearden[8]

- Dominique Sanda as Mrs Smith

- James Mason as Sir George Wheeler MP

- Harry Andrews as Mackintosh

- Ian Bannen as Ronald Slade

- Michael Hordern as Brown

- Nigel Patrick as Soames-Trevelyan

- Peter Vaughan as Inspector Brunskill

- Roland Culver as The Judge

- Percy Herbert as Taafe

- Robert Lang as Jack Summers

- Leo Genn as Rollins

- Jenny Runacre as Gerda

- John Bindon as Buster

- Hugh Manning as The Prosecutor

- Wolfe Morris as Maltese Police Commissioner

- Noel Purcell as O'Donovan

- Donald Webster as Jervis

- Keith Bell as Palmer

- Niall MacGinnis as Warder

- Eddie Byrne as Fisherman

- Shane Briant as Cox

- Joe Lynch as Garda

- Donal McCann and Tom Irwin as Firemen

Production

[edit]Scripting

[edit]The script was written by Walter Hill who later recalled it as an unhappy experience. He was having a legal dispute with Warner Bros over the fact they had sold his script for Hickey & Boggs to United Artists without paying Hill any extra money. As a compromise, Warners sent Hill some novels they had optioned and offered to pay for him to write the script for one. He selected The Freedom Trap by Desmond Bagley.[9] The 1971 novel was loosely based on the exposure and defection of George Blake, a Soviet mole in MI6.[10][11]

Hill said, "I wrote a quick script which I was not particularly enamored with myself" and "much to my shock and surprise" Paul Newman agreed to star and John Huston wanted to direct. Newman's producing partner John Foreman would produce.[9][12] The film was financed by Warners as part of the slate of films for Dick Shepherd.[13]

"One would like to think you are mistaken about the wonders of your work, but I didn't believe it", said Hill. "That part turned out to be true."[9]

Hill worked on the script with Huston and says the director was ill. Although Hill ended up with sole screen credit, he says, "I wrote 90% of the first half, various people wrote the rest. I didn't think it was a very good film."[9]

William Fairchild was one of the uncredited writers on the script.[14]

Shooting

[edit]According to a contemporary article on the making of the film, the script was not completed two weeks into shooting.[15]

The film was shot in England, Republic of Ireland and Malta. The scene where Slade and Rearden escape from prison was inspired by Blake's escape from Wormwood Scrubs in 1966. The jail scenes were filmed at Liverpool Prison and Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin, Ireland.

The house where Slade and Rearden stay after their escape is Ardfry house, Oranmore, county Galway, Ireland, an abandoned castle in ruins.[16]

The scene in which Rearden realises that Slade is on board Wheeler's yacht was shot at Roundstone, County Galway, Ireland.

Reception

[edit]The film received a mixed reception when it was released, and did not perform well at the box office, in either the United Kingdom, United States or Canada. David Robinson, reviewer for The Times, found the story a very predictable and typical espionage thriller, while the direction by John Huston still made it watchable because of Huston's gift for storytelling.[1] Variety wrote it was "a tame tale of British espionage and counter-espionage", and added that "there's a whole lot of nothing going on here."[17] The Hollywood Reporter called it "a good genre film in the ice cold vein of The Maltese Falcon", and though "it isn't nearly as rich nor fine as that early Huston classic but tells an interesting story with a sure sense of atmosphere, location and supporting characters."[18] Roger Ebert wrote it was "perhaps the first anti-spy movie", as it "seems to have been made by a group of people with no sympathy or understanding for spy movies."[19] Time Out called it a "reasonably entertaining old-fashioned thriller" "if you can accept Newman as a totally unconvincing Australian..., an appalling array of accents (mainly Irish), and Dominique Sanda as an unlikely member of the British Secret Service."[20]

Walter Hill says he never saw the final product, but was told it was "a real bomb".[21]

Notes

[edit]- ^ More specifically, HM Prison Chelmsford.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Film reviews". The Times. 9 November 1973. p. 17 – via The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "The Mackintosh Man (1973)". BFI. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1973". Variety. 9 January 1974. p. 60.

- ^ "The Village Voice – The Mackintosh Man". The Village Voice. 2 May 1974. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ "The Mackintosh Man - Rotten Tomatoes". www.rottentomatoes.com. 11 June 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Phillips, Gene D. "Talking with John Huston". Film Comment. Vol. 9, no. 3, (May/Jun 1973). New York. pp. 15–19.

- ^ Kapica, Jack (17 August 1973). "The Mackintosh man – he keeps you guessing". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Interview with Walter Hill Chapter 3" Directors Guild of America accessed 12 July 2014

- ^ Newgate Callendar. "Criminals at Large". The New York Times; Hill signed to do the script in January 1972.

- ^ Murphy, Mary (27 January 1972). "MOVIE CALL SHEET: Janet Leigh Set for Role in 'Rabbits'". Los Angeles Times. p. f12.

- ^ Haber, Joyce. (1 August 1972). "Nixon Casts a Vote for 'Skyjacked'". Los Angeles Times. p. h11.

- ^ Haber, Joyce (23 October 1972). "Networks' September Song Souring". Los Angeles Times. p. d14.

- ^ Vollmer, Lucie. (20 December 1972). "MOVIE CALL SHEET: Groucho Set in Documentary". Los Angeles Times. p. c23.

- ^ Robinson, David. "The Innocent Bystander", Sight and Sound; London Vol. 42, Iss. 1,

- ^ An Taisce/The National Trust for Ireland

- ^ Variety Staff (1 January 1973). "The Mackintosh Man". Variety. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "'The MacKintosh Man': THR's 1973 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. 25 July 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (15 August 1973). "The Mackintosh Man movie review". www.rogerebert.com. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "The Mackintosh Man". Time Out London. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "Hard Ridingauthor=Greco, Mike". Film Comment. Vol. 16, no. 3 (May/Jun 1980). pp. 13–19, 80.

External links

[edit]- 1973 films

- Warner Bros. films

- American spy thriller films

- British spy thriller films

- Films directed by John Huston

- Cold War spy films

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on thriller novels

- Films set in Ireland

- Films set in England

- Films set in London

- Films set in Malta

- Films shot in Malta

- Films shot in Ireland

- Films scored by Maurice Jarre

- Films with screenplays by Walter Hill

- 1970s spy thriller films

- 1970s American films

- 1970s British films

- 1970s English-language films

- English-language spy thriller films