Trinity College (Connecticut)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2023) |

| |

Former names | Washington College (1823–1845) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Pro Ecclesia Et Patria (Latin) |

Motto in English | For Church and Country |

| Type | Private liberal arts college |

| Established | May 1823 |

| Accreditation | NECHE |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $780 million (2022)[1] |

| President | Joanne Berger-Sweeney |

Academic staff | 230 full-time and 45 part-time (spring 2022)[2] |

| Students | 2,241 (spring 2022)[2] |

| Undergraduates | 2,200 (spring 2022)[2] |

| Postgraduates | 41 (spring 2021)[3] |

| Location | , U.S. 41°44′49″N 72°41′24″W / 41.747°N 72.690°W |

| Campus | Urban, 100 acres (40 ha) |

| Colors | Blue and gold |

| Nickname | Bantams |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division III – NESCAC |

| Mascot | Bantam |

| Website | www |

Trinity College is a private liberal arts college in Hartford, Connecticut, United States. Founded as Washington College in 1823, it is the second-oldest college in the state of Connecticut. Coeducational since 1969, the college enrolls 2,235 students.[3] Trinity offers 41 majors and 28 interdisciplinary minors.[4] The college is a member of the New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC).

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]

Bishop Thomas Brownell opened Washington College in 1824 to nine male students[5] and the vigorous protest of Yale alumni.[clarification needed] A 14-acre site was chosen, at the time about a half-mile from the city of Hartford.

The college was renamed Trinity College in 1845; the original campus consisted of two Greek Revival buildings. One of the Greek Revival buildings housed a chapel, library, and lecture rooms. The other was a dormitory for the male students.[6]

In 1872, Trinity College was persuaded by the state to move from its downtown "College Hill" location (now Capitol Hill, site of the state capitol building) to its current 100-acre (40 ha) campus a mile southwest. Although the college sold its land overlooking the Park River and Bushnell Park in 1872, it did not complete its move to its Gallows Hill campus until 1878.[7] The original plans for the Gallows Hill site were drawn by the noted Victorian architect William Burges but were too ambitious and too expensive to be fully realized. Only one section of the proposed campus plan, the Long Walk, was completed.

By 1889, the library contained 30,000 volumes, and the school graduated over 900 students.[8] Enrollment reached 122 in 1892.

20th century

[edit]President Remsen Ogilby (1920–1943) enlarged the campus, and more than doubled the endowment. The faculty grew from 25 to 62, and the student body from 167 to 530 men. Under President Keith Funston (1943–1951), returning veterans expanded the enrollment to 900.[5]

In 1962, Connecticut Public Television (CPTV) began its first broadcasts in the Trinity College Public Library, and later in Boardman Hall, a science building on campus.[9][10]

In 1968, the trustees voted to withdraw from the Association of Episcopal Colleges.[11] Also in 1968, the trustees of Trinity College voted to make a commitment to enroll more minority students, providing financial aid as needed. This decision was preceded by a siege of the administrative offices in the Downes and Williams Memorial buildings during which Trinity students would not allow the president or trustees to leave until they agreed to the resolution.[12]

In 1969, Trinity College became coeducational and admitted its first female students, as transfers from Vassar College and Smith College.[13]

Academics

[edit]

Trinity offers undergraduate degrees in 41 majors with options of 28 minors and a self-designed major, and Masters of Arts in a few subjects. Trinity is part of a small group of liberal arts schools that offer degrees in engineering. Trinity has a student-to-faculty ratio of 9:1.[14] Its most popular undergraduate majors, by number out of 517 graduates in 2022, were:

- Political Science and Government (80)

- Economics (64)

- Psychology (41)

- Econometrics and Quantitative Economics (38)

- Engineering (28)

- Neuroscience (24)

- Biology/Biological Sciences (23)[15]

Trinity College, Rome Campus

[edit]Trinity College, Rome Campus (TCRC), is a study abroad campus of Trinity College. It was established in 1970 and is in a residential area of Rome on the Aventine Hill close to the Basilica of Santa Sabina within the precincts of a convent run by an order of nuns.[16]

Admissions

[edit]

The 2020 annual ranking by U.S. News & World Report categorizes Trinity as "more selective".[17]

For the Class of 2022 (enrolling fall 2018), Trinity received 6,096 applications, accepted 2,045 (33.5%) and enrolled 579.[18]

As of fall 2015, Trinity College does not require the SAT or ACT for students applying for admission.[19] Of the 31% of enrolled freshmen submitting SAT scores, the middle 50% range was 630–710 for evidence-based reading and writing, and 670–750 for math, while of the 23% of enrolled freshmen submitting ACT results, the middle 50% range for the composite score was 29–32.[18]

Rankings and reputation

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| Liberal arts | |

| U.S. News & World Report[20] | 39 |

| Washington Monthly[21] | 38 |

| National | |

| Forbes[22] | 62 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[23] | 104 |

In 2022, Forbes magazine ranked Trinity College 12th amongst all liberal arts universities and 62nd amongst all colleges and universities.[24] U.S. News & World Report ranked Trinity 39th in its 2022 ranking of best national liberal arts colleges in the United States. It was also ranked 46th for best value school.[25] However, these US News rankings likely reflect that Trinity joined the "Annapolis Group" in August 2007, an organization of more than 100 of the nation's liberal arts schools, in refusing to participate in the magazine's rankings.[26][27] Trinity College is accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education.[28]

In 2016, authors Howard and Matthew Greene continued to include Trinity in the third edition of Hidden Ivies: 63 Top Colleges that Rival the Ivy League.[29] The Princeton Review has given Trinity a 93 (out of 99) for selectivity and in 2017 named Trinity as a best value college. Money.com magazine ranked Trinity College 55th among all colleges and universities in the nation.[30][31]

Student life

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[32] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 61% | ||

| Foreign national | 14% | ||

| Hispanic | 9% | ||

| Black | 6% | ||

| Asian | 4% | ||

| Other[a] | 4% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[b] | 13% | ||

| Affluent[c] | 87% | ||

Mascot

[edit]

Trinity's mascot, the bantam, was conceived by Joseph Buffington, class of 1875, who was a federal judge and trustee of the college.[33]

Student publication

[edit]The Trinity Tripod, founded in 1904, is Trinity College's student newspaper.

Fraternities and sororities

[edit]According to the college, 18% of the student body are affiliated with a Greek organization.[34]

In 2012, then-president James F. Jones proposed a social policy for Trinity College which made a commitment, among other things, to require all sororities and fraternities to achieve gender parity within two years or face closure. Trinity College's co-ed mandate for fraternities and sororities was withdrawn in September 2015 and replaced with the "Campaign for Community" effort to establish more inclusive social traditions on campus.[35]

Trinity currently has several sororities and fraternities:[36]

Hartford campus

[edit]

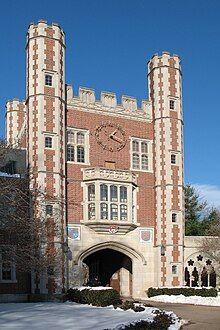

Long Walk buildings

[edit]The first buildings completed on the current campus were Seabury and Jarvis halls in 1878. Together with Northam Towers, these make up what is known as the "Long Walk". These buildings are an early example of Collegiate Gothic architecture in the United States, built to plans drawn up by William Burges, with F.H. Kimball as supervising architect. The Long Walk has been expanded and is connected with several other buildings. On the northernmost end there is the chapel, whose western side is connected to the Downes and Williams Memorial building. Heading south, the next building is Jarvis Hall, named after Abraham Jarvis. Jarvis becomes Northam Towers heading south, then Seabury Hall. Seabury Hall, named for Samuel Seabury, is connected to Hamlin Hall. To Hamlin's east is Cook, then Goodwin and then Woodward. The dormitories on the Long Walk end there, and the terminal building on the south end of the long walk is Clement/Cinestudio. Clement is the chemistry building; Cinestudio a student run movie theater. If one travels to the south of Hamlin there will be Mather Hall and the Dean of Students Office.[37]

Main quadrangle

[edit]

Trinity's campus features a central green known as the Main Quad, designed by famed architect Frederick Law Olmsted. The large expanse of grass is bound on the west by the Long Walk, on the east by the Lower Long Walk, on the north by the chapel, and on the south by the Cook and Goodwin-Woodward dormitories. Trinity's green is notable for its unusually large, rectangular size, running the entire length of the Long Walk and with no walkways traversing it. Trees on the Quad have been planted in a 'T' configuration (for Trinity) with the letter's base at the statue of Bishop Brownell (built 1867).[38] and its top running the length of the Long Walk.

Film

[edit]Cinestudio is an art cinema with 1930s-style design. An article in the Hartford Advocate described this non-profit organization, which depends solely on grants and the efforts of volunteer workers who are paid in free movies.[39]

Music

[edit]Trinity College hosts the Albert Schweitzer Organ Festival, one of the top competitions for young organists in North America.[40] The festival features performances on the chapel organ, which was designed by Charles Nazarian, a college alumnus and pipe organ designer, in consultation with Clarence Watters, who was the chapel organist and head of the college's music department from 1932 to 1967.[41] The organ incorporates pipes from the chapel’s original 1932 Aeolian-Skinner organ and was built in 1971 by Austin Organs of Hartford.

The Chapel Singers perform concerts on campus as well as on domestic and international tours. Trinity also hosts the annual Trinity International Hip Hop Festival. The festival was founded in 2006 with the goal of unifying Trinity with the city of Hartford.[42]

Since 2006, Trinity's WRTC FM radio station has broadcast the Trinity Samba Fest from the Hartford waterfront featuring regional and international talent.[43][44][45]

Academic regalia

[edit]Trinity followed the European pattern of using academic regalia from its foundation,[46] and was one of only four US institutions (all associated with the Episcopal Church) to assign gowns and hoods for its degrees in 1883.[47] There were six degrees awarded at the time, all taking a black gown of silk or stuff and a hood of black silk lined according to the degree: B.A. white silk, M.A. dove-colored silk, B.D. crimson silk, D.D. scarlet silk, L.L.D. pink silk, Mus.D. purple silk.[47]

In 1894, a year before the introduction of the intercollegiate code on academic costume, the college brought in a new scheme of academic regalia. The hoods and gowns followed the shape of those used at the University of Oxford except that the hood for Doctors of Divinity was of the shape used at the University of Cambridge.

A variety of different colours and fabrics were used for the hoods: B.A. black stuff edged palatinate purple, B.S. black stuff edged light blue silk, B.Litt. black stuff edged russet brown silk, B.D. black silk edged scarlet silk (not in use by 1957), L.L.B. black silk edged dark blue silk (not in use by 1957), Mus.B. black silk edged pink silk (not in use by 1957), M.A. black silk lined palatinate purple silk, M.S. black stuff lined light blue silk, D.D. scarlet cloth lined black silk, D.Litt. scarlet silk-lined russet brown silk, L.L.D. scarlet silk lined dark blue silk, D.C.L. crimson silk lined black silk, Mus.D. white silk-lined pink silk, D.Sc. black silk lined light blue silk, Ph.D. black silk lined people silk (not in use by 1957), M.D. scarlet silk lined maroon silk (not in use by 1957).[46][48]

D.P.H. black cloth lined salmon pink silk (1945), D.H.Litt. scarlet silk-lined people silk (1947), D.Hum. white silk-lined crimson (1957), and D.S.T. scarlet silk-lined blue with a gold chevron (1957) were later added.[46]

As of 2018, the hoods for doctorates (except the Ph.D. and M.D.) and for the M.Mus. remain in use for honorary degrees, with the further addition since 1957 of the D.F.A. wrote lined white with a red Chevron.[49]

Notable alumni

[edit]This article's list of alumni may not follow Wikipedia's verifiability policy. (April 2024) |

-

Tucker Carlson, right wing political commentator formerly employed by Fox News

-

Christine Quinn, former Speaker of the New York City Council

-

David Chang, restaurateur and television personality

-

Jesse Watters, conservative commentator and Fox News host

-

Edward Albee, playwright

-

Ari Graynor, actress

-

Kelly Killoren Bensimon, cast member on The Real Housewives of New York City

-

Danny Meyer, founder of Shake Shack

-

George Will, libertarian-conservative political commentator and author

-

Mary McCormack, actress

-

Jane Swift, former Acting Governor of Massachusetts

-

Stephen Gyllenhaal, film director

-

Rachel Platten, singer-songwriter

Trinity College's distinguished alumni include many influential and historical people, including governors, US Cabinet members, federal judges, political commentators and journalists, and senior executives in business and industry.

Notable alumni of Trinity College include:

- Kristine Belson, Class of 1986, president of Sony Pictures Animation and Oscar-nominated film producer (The Croods)

- S. Prestley Blake, co-founder of Friendly's

- Joseph Buffington, judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

- Tucker Carlson, Class of 1991, political commentator, co-founder of The Daily Caller, former host of Fox News Channel's Tucker Carlson Tonight, former host of Fox Nation's Tucker Carlson Today

- Tom Chappell, founder of Tom's of Maine

- Martin W. Clement, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, 1935 to 1948.

- Percival W. Clement, 57th Governor of Vermont

- Thomas R. DiBenedetto, president of Boston International Group, owner and former chairman of AS Roma

- Edward Miner Gallaudet, first president of Gallaudet University

- David Gottesman, billionaire, founder of First Manhattan Co., and member of Berkshire Hathaway's board of directors

- Henry McBride, fourth Governor of Washington State

- Mary McCormack, actress (In Plain Sight, The West Wing). Her two siblings are also Trinity graduates. Bridget McCormack is Chief Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court, and Will McCormack is an actor.

- Mitchell M. Merin, former president and chief operating officer of Morgan Stanley Investment Management

- James Murren, chairman of the board and chief executive officer of MGM Resorts International

- Neil Patel, American lawyer, conservative political advisor to Vice President Dick Cheney, publisher and co-founder of The Daily Caller

- Gregory Anthony Perdicaris, first U.S. Consul to Greece

- Charles R. Perrin, chairman of Warnaco, former chairman and CEO of Avon Products and of Duracell

- Rachel Platten, singer-songwriter

- William C. Richardson, board director of Exelon; former president of Johns Hopkins University

- Jane Swift, Class of 1987, former Acting Governor of Massachusetts

- J. H. Hobart Ward, US Army general

- Jesse Watters, Class of 2001, conservative commentator, host of Jesse Watters Primetime, and co-host of The Five on Fox News

- John Williams, eleventh presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States

- Leo Wise (1849–1933), newspaper editor and publisher

- Charles C. Van Zandt, 34th Governor of Rhode Island

Notes

[edit]- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

[edit]- ^ As of March 7, 2022. U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2021 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY20 to FY21 (Report). National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ a b c "College Navigator - Trinity College".

- ^ a b "Common Data Set 2018–2019, Part B" (PDF). Trinity College.

- ^ "Majors and Minors". Academics. Trinity College. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Albert E. Van Dusen, Connecticut (1961) pp 362-63

- ^ Albert E. Van Dusen, Connecticut (1961) pp 362–63

- ^ "Trinity College". Trincoll.edu. Archived from the original on January 10, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ Hartford, Conn., as a manufacturing, business and commercial center; with brief sketches of its history, attractions, leading industries, and institutions . Hartford, CT: Hartford (Conn) Board of Trade. 1889. pp. 182–187. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ "Our History | Connecticut Public Broadcasting Network". Cpbn.org. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- ^ "CPTV Celebrates 50 Years: Present at the Creation - Connecticut Magazine - April 2013 - Connecticut". Connecticutmag.com. October 1, 1962. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- ^ Knapp, Peter J. (Peter Jonathan), 1943- (2000). Trinity College in the twentieth century : a history. Knapp, Anne H. Hartford, Conn.: Trinity College. p. 209. ISBN 0-911534-59-8. OCLC 45273021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Exit Interview with Dr. Theodore Davidge Lockwood". Publications About Trinity. May 1981. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Carlesso, Jenna (January 24, 2019). "Former Trinity College president, known for admitting the school's first female students, dies". Hartford Courant. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Overview". U.S. News Best Colleges. U.S. News. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "Trinity College". nces.ed.gov. U.S. Dept of Education. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ "The Trinity College Rome Campus". trincoll.edu.

- ^ "Trinity College". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "Common Data Set 2018–2019, Part C" (PDF). Trinity College.

- ^ "Application Process". Trinity College. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "2024-2025 National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "Trinity College (CT)". Forbes. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ "Trinity College – Profile, Rankings and Data | US News Best Colleges".

- ^ "Best National Liberal Arts Colleges". April 6, 2015.

- ^ "TRINITY COLLEGE JOINS GROUP OF TOP LIBERAL ARTS SCHOOLS WITHDRAWING FROM U.S. NEWS & WORLD REPORT'S COLLEGE RANKINGS" (Press release). Trinity College. August 16, 2007. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ Connecticut Institutions – NECHE, New England Commission of Higher Education, retrieved May 26, 2021

- ^ Greene, Howard; Greene, Matthew (2016). The Hidden Ivies, third Edition: 63 of America's Top Liberal Arts Colleges and Universities. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-242090-9.

- ^ "Trinity College (CT) – the Princeton Review College Rankings & Reviews".

- ^ "The Best Colleges in America, Ranked by Value". Money.com. May 16, 2022. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022.

- ^ "College Scorecard: Trinity College". United States Department of Education. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ "Trinity Traditions". library.trincoll.edu. Archived from the original on September 22, 2009.

- ^ e. "Trinity College - College Facts". Trincoll.edu. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ "Important Message about Student Life". trincoll.edu. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ "Organizations". Trinity College (Connecticut). Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- ^ http://www.trincoll.edu/NR/rdonlyres/49EA971F-5F57-43DA-A0F0-A276AE77F148/0/CampusMap2009.pdf [dead link]

- ^ Thomas, Grace Powers (1898). Where to educate, 1898-1899. A guide to the best private schools, higher institutions of learning, etc., in the United States. Boston: Brown and Company. p. 26. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ "About". Cinestudio. September 25, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ Albert Schweitzer Organ Festival. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Trinity College, Hartford: The Organ. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ "World hip-hop questions US rap". BBC News. April 29, 2006. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- ^ "Samba Fest" (Press release). Trinity College.

- ^ Hamad, Michael (April 30, 2015). "Samba Fest: A Day Of Brazilian Culture, Music, Food". Hartford Courant.

- ^ Boyer, Brian; Dell, Barbara Glassman. "Ninth Annual Samba Fest at Hartford Riverfront, May 2". MetroHartford Alliance.

- ^ a b c Academic Costume. May 1957. p. 7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b T. W. Wood (1883). The degrees, gowns and hoods of the British, Colonial, Indian and American universities and colleges. Thomas Pratt and Sons, London. pp. 31–36.

- ^ C. A. Ealand, ed. (1920). Athena. Macmillan, New York. p. 118.

- ^ "Commencement Program" (PDF). 2018. p. 34. Retrieved May 16, 2020.