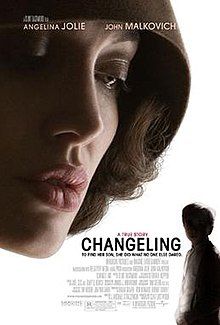

Changeling (film)

| Changeling | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

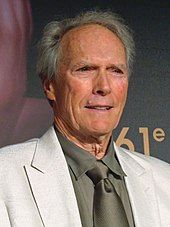

| Directed by | Clint Eastwood |

| Written by | J. Michael Straczynski |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Tom Stern |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Clint Eastwood |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 142 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $55 million |

| Box office | $113.4 million |

Changeling is a 2008 American mystery crime drama film directed, produced, and scored by Clint Eastwood and written by J. Michael Straczynski.[1] The story was based on real-life events, specifically the 1928 Wineville Chicken Coop murders in Mira Loma, California. It stars Angelina Jolie as a woman united with a boy who she realizes is not her missing son. When she tries to demonstrate that to the police and city authorities, she is vilified as delusional, labeled as an unfit mother and confined to a psychiatric ward. The film explores themes of child endangerment, female disempowerment, political corruption, and mistreatment of mental health patients.

Working in 1983 as a special correspondent for the now defunct TV-Cable Week magazine, Straczynski first learned the story of Christine Collins and her son from a Los Angeles City Hall contact.[2] Over the ensuing years he kept researching the story but never felt he was ready to tackle it. Out of television writing for several years and known to be difficult to work with, he returned to researching and then finally writing the story in 2006.[3] Almost all of the film's script was drawn from thousands of pages of documentation.[Note 1] His first draft became the shooting script; it was his first film screenplay to be produced. Ron Howard had intended to direct the film, but scheduling conflicts led to his replacement by Eastwood. Howard and his Imagine Entertainment partner Brian Grazer produced Changeling alongside Malpaso Productions' Robert Lorenz and Eastwood. Universal Pictures financed and distributed the film.

Several actors campaigned for the leading role; ultimately, Eastwood decided that Jolie's face would suit the 1920s period setting. The film also stars Jeffrey Donovan, Jason Butler Harner, John Malkovich, Michael Kelly and Amy Ryan. While some characters are composites, most are based on actual people. Principal photography, which began on October 15, 2007, and concluded a few weeks later in December, took place in Los Angeles and other locations in southern California. Actors and crew noted that Eastwood's low-key direction resulted in a calm set and short working days. In post production, scenes were supplemented with computer-generated skylines, backgrounds, vehicles and people.

Changeling premiered to critical acclaim at the 61st Cannes Film Festival on May 20, 2008. Additional festival screenings preceded a limited release in the United States on October 24, 2008, followed by a general release in North America on October 31, 2008; in the United Kingdom on November 26, 2008; and in Australia on February 5, 2009. Critical reaction was more mixed than at Cannes. While the acting and story were generally praised, the film's "conventional staging" and "lack of nuance" were criticized. Changeling earned $113 million in box-office revenue worldwide—of which $35.7 million came from the United States and Canada.[4]

Changeling earned Jolie numerous award nominations including the Academy Award for Best Actress, the BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role, the Critics' Choice Movie Award for Best Actress, the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama and the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role.

Plot

[edit]In 1928 Los Angeles, single mother Christine Collins returns home to find her 9-year-old son, Walter, missing. Reverend Gustav Briegleb publicizes Christine's plight and rails against the LAPD for incompetence, corruption and the extrajudicial punishment meted out by its "Gun Squad," led by Chief James E. Davis. Some six months later, the LAPD tells Christine that Walter has been found alive and organizes a reunion in front of the press. The boy claims to be Walter but Christine knows he is not. Captain J.J. Jones, the head of the LAPD's Juvenile Division, insists he is and pressures Christine into taking him home "on a trial basis."

Christine finds the boy – unlike Walter – is circumcised and is several inches shorter. Jones has a doctor tell her that trauma has shrunk his spine, and that whoever took Walter must have had him circumcised. A newspaper story implies that Christine is an unfit mother; Briegleb says it was planted by police to discredit her. Walter's teacher and dentist both sign letters asserting the boy is not Walter. When Christine tells her story to the press Jones has her committed to Los Angeles County Hospital's psychopathic ward. Inmate Carol tells Christine she is one of several women sent there for challenging police authority. Dr. Steele diagnoses Christine as delusional, forces her to take medication, and says he will only release her if she signs an admission that she was mistaken about Walter's identity.

Detective Lester Ybarra travels to a Wineville ranch to deport 15-year-old Sanford Clark to Canada. Clark's uncle, Gordon Stewart Northcott, has fled. Clark tells Ybarra that Northcott forced him to help kidnap and murder 20 children. He identifies Walter as one of them, and digs up body parts. Briegleb secures Christine's release with a newspaper story naming Walter as a possible victim in the Wineville killings. Walter's impostor (Arthur Hutchins) reveals that the police told him to lie about being Christine's son. The police capture Northcott in Vancouver, Canada. Famed attorney Sammy "S.S." Hahn takes on Christine's case pro bono and secures the release of the other women whom the police wanted to silence.

Christine, Hahn, and Briegleb arrive at Los Angeles City Hall for the city council's hearing, where crowds are protesting. The council concludes that Jones and Davis be removed from duty and that extrajudicial internments by police must stop. Northcott's jury finds him guilty of murder and he is sentenced to death by hanging.

In 1930, Northcott sends Christine a message saying if she visits him, he will admit to killing Walter. When she visits, Northcott refuses to tell her. He is executed the next day.

In 1935, David Clay, assumed to have been one of those murdered, is found alive. He reveals that he was imprisoned with Walter and that Walter helped him escape. They became separated and David does not know if Walter was recaptured, but Christine gains hope that he could still be alive.

Epilogue text states that Captain Jones was suspended, Chief Davis was demoted, and Mayor George Cryer did not run for re-election; that California made it illegal to commit people to psychiatric facilities based solely on the word of authorities; that Rev. Briegleb continued to use his radio show to expose police misconduct and political corruption; that Wineville changed its name to Mira Loma to escape the stigma of the murders; and that Christine Collins never stopped searching for her son.

Cast

[edit]- Angelina Jolie as Christine Collins

- John Malkovich as Reverend Gustav Briegleb

- Jeffrey Donovan as Captain J.J. Jones

- Michael Kelly as Detective Lester Ybarra

- Colm Feore as Chief James E. Davis

- Jason Butler Harner as Gordon Stewart Northcott

- Eddie Alderson as Sanford Wesley Clark

- Wendy Worthington as Reception Nurse

- Riki Lindhome as Examination Nurse

- Hope Shapiro as Medication Nurse

- Amy Ryan as Carol Dexter

- Geoff Pierson as Sammy "S.S." Hahn

- Denis O'Hare as Dr. Jonathan Steele

- Frank Wood as Ben Harris

- Peter Gerety as Dr. Earl W. Tarr

- Reed Birney as Mayor George E. Cryer

- Gattlin Griffith as Walter Collins

- Dale Dickey as Patient

- Jim Cantafio as Desk Sergeant

- Devon Gearhart as Winslow Boy

Historical context

[edit]In 1926, 13-year-old Sanford Clark was taken from his home in Saskatchewan (with the permission of his mother and reluctant father) by his uncle, 19-year-old Gordon Stewart Northcott.[5] Northcott took Clark to a ranch in Wineville, California, where he regularly beat and sexually abused the boy—until August 1928, when the police took Clark into custody after his sister, 19-year-old Jessie Clark, informed them of the situation.[6] Clark revealed that he was forced to help Northcott and his mother, Sarah Louise Northcott, in killing four young boys after Northcott had kidnapped and molested them.[6][7] The police found no bodies at the ranch—Clark said they were dumped in the desert. However, Clark told police where the bodies had initially been buried on the Northcott property. Clark pointed out the initial burial location on the property and police discovered body parts, blood-stained axes and personal effects belonging to missing children. The Northcotts fled to Canada, but were arrested and extradited to the United States. Sarah Louise initially confessed to murdering Walter Collins, but she later retracted her statement which was rejected by the Judge; Gordon, who had confessed to killing four boys, did likewise.[7]

Christine Collins (the mother of Walter Collins) was placed in Los Angeles County Hospital by Captain Jones. After her release, she sued the police department twice, winning the second lawsuit. Although Captain Jones was ordered to pay Collins $10,800, he never did.[8] A city council welfare hearing recommended that Jones and Chief of Police James E. Davis leave their posts, but both were later reinstated. The California State Legislature later made it illegal for the police to commit someone to a psychiatric facility without a warrant.[9] Northcott was convicted of the murders of Lewis Winslow (12), Nelson Winslow (10) and an unidentified Mexican boy;[6] after his conviction, Northcott was reported to have admitted to up to 20 murders, though he later denied the claim.[6][9] Northcott was executed by hanging in 1930 at the age of 23. Sarah Louise was convicted of Walter Collins' murder and was sentenced to life in prison, but was paroled after 12 years of incarceration.[6] In 1930, the residents of Wineville changed the town's name to Mira Loma to escape the notoriety brought by the case.[7]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Several years before writing Changeling, television screenwriter and former journalist J. Michael Straczynski was contacted by a source at Los Angeles City Hall. The source told him that officials were planning to burn numerous archive documents,[10] among them "something [Straczynski] should see". The source had discovered a transcript of the city council welfare hearings concerning Collins and the aftermath of her son's disappearance.[11] Straczynski became fascinated with the case;[12] he carried out some research[13] and wrote a spec script titled The Strange Case of Christine Collins. Several studios and independent producers optioned the script, but it never found a buyer.[14] Straczynski felt he lacked the time needed to devote to making the story work and only returned to the project following the cancellation of his television series Jeremiah in 2004.[13] After 20 years as a screenwriter and producer for television, Straczynski felt he needed a break from the medium,[12] so he spent a year researching the Collins case through archived criminal, county courthouse, city hall and city morgue records.[15] He said he collected around 6,000 pages of documentation on Collins and the Wineville murders,[10] before learning enough to "figure out how to tell it".[12] He wrote the first draft of the new script in 11 days.[13] Straczynski's agent passed the script to producer Jim Whitaker. He forwarded it to Ron Howard,[15] who optioned it immediately.[12]

In June 2006, Universal Studios and Howard's Imagine Entertainment bought the script for Howard to direct. The film was on a short list of projects for Howard after coming off the commercial success of The Da Vinci Code.[16] In March 2007, Universal fast-tracked the production. When Howard chose Frost/Nixon and Angels & Demons as his next two directing projects, it became clear he could not direct Changeling until 2009.[17] After Howard stepped down, it looked as if the film would not be made, despite admiration for the script in the industry.[18] Howard and Imagine partner Brian Grazer began looking for a new director to helm the project;[19] they pitched the film to Eastwood in February 2007,[10] and immediately after reading the script he agreed to direct.[20] It would be Eastwood's first production for Universal Pictures since The Eiger Sanction in 1975. After that film's production, Eastwood relocated to Warner Bros., where he has been (with a few exceptions) since 1976. Eastwood said his memories of growing up during the Great Depression meant that whenever a project dealing with the era landed in his hands, he "redoubled his attention" to it.[21] He also cited the script's focus on Collins—rather than the "Freddy Krueger" story of Northcott's crimes—as a factor in deciding to make the film.[10]

Writing

[edit]Straczynski viewed "sitting down and ferreting out [the] story" as a return to his journalistic roots. He also drew on his experience writing crime drama for the procedural elements of the plot.[13] Straczynski said he had gathered so much information about the case that it was difficult to work out how to tell it. To let the story develop at its own pace, he put the project aside to allow himself to forget the less essential elements and bring into focus the parts he wanted to tell. He described what he saw as two overlaid triangles: "the first triangle, with the point up, is Collins' story. You start with her, and her story gets broader and broader and begins having impact from all kinds of places. The overlay on that was an upside down triangle with the base on top, which is the panorama of Los Angeles at that time—1928. And it begins getting narrower and narrower toward the bottom, bearing down on her." Once Straczynski saw this structure, he felt he could write the story.[22] He chose to avoid focusing on the atrocities of the Wineville murders in favor of telling the story from Collins' perspective;[23] Straczynski said she was the only person in the story without a hidden agenda,[22] and it was her tenacity—as well as the legacy the case left throughout California's legal system—that had attracted him to the project. He said, "My intention was very simple: to honor what Christine Collins did."[24]

"The story is just so bizarre that you need something to remind you that I'm not making this stuff up. So it seemed important to me to put in those clippings because you reach the part of the story where you go, 'Come on he's got to have gone off the rails with this.' Turn the page and there is indeed an article confirming it, which is why, in terms of writing the script, I [hewed] very close to the facts. The story is already extraordinary enough."

With Collins as the inspiration, Straczynski said he was left with a strong desire "to get it right"; he approached it more like "an article for cinema" than a regular film.[13][22] He stuck close to the historical record because he felt the story was bizarre enough that adding too many fictional elements would call into question its integrity.[22] Straczynski claimed that 95% of the script's content came from the historical record;[15] he said there were only two moments at which he had to "figure out what happened", due to the lack of information in the records. One was the sequence set in the psychopathic ward, for which there was only limited after-the-fact testimony.[11] Straczynski originally wrote a shorter account of Collins' incarceration. His agent suggested the sequence needed development, so Straczynski extrapolated events based on standard practice in such institutions at the time. It was at this stage he created composite character Carol Dexter, who was intended to symbolize the women of the era who had been unjustly committed.[22] Straczynski cited his academic background, including majors in psychology and sociology, as beneficial to writing the scenes, specifically one in which Steele distorts Collins' words to make her appear delusional.[13] Straczynski worked at making the dialogue authentic, while avoiding an archaic tone. He cited his experience imagining alien psyches when writing Babylon 5 as good practice for putting himself in the cultural mindset of the 1920s.[22]

Straczynski described specific visual cues in the screenplay, such as in Sanford Clark's confession scene. Clark's flashback to a falling axe is juxtaposed with the crumbling ash from Detective Ybarra's cigarette. The image served two purposes: it was an aesthetic correlation between the axe and the cigarette, and it suggested that Ybarra was so shocked by Clark's confession that he had not moved or even smoked in the 10 minutes Clark took to tell his story. As with most of the cues, Eastwood shot the scene as written.[22] To ensure the veracity of the story, Straczynski incorporated quotes from the historical record, including court testimony, into the dialogue. He also included photocopies of news clippings every 15–20 pages in the script to remind people the story was a true one.[24] So the credits could present the film as "a true story" rather than as "based on" one, Straczynski went through the script with Universal's legal department, providing attribution for every scene.[25] Straczynski believed the only research error he made was in a scene that referenced Scrabble, pre-dating its appearance on the market by two years. He changed the reference to a crossword puzzle.[13] He did not alter the shooting script any further from his first draft;[26] though Straczynski had written two more drafts for Howard, Eastwood insisted the first draft be filmed as he felt it had the clearest voice of the three.[22] Straczynski said, "Clint's funny—if he likes it, he'll do it, that's the end of the discussion. When I met with him to ask, 'Do you want any changes, do you want any things cut, added to, subtracted from, whatever', he said, 'No. The draft is fine. Let's shoot the draft.'"[11]

Among the changes Straczynski made from the historical record was to omit Northcott's mother—who participated in the murders—from the story, as well as the fact that Northcutt had sexually abused his victims. He also depicted Northcott's trial as taking place in Los Angeles, though it was held in Riverside.[27] The title is derived from Western European folklore and refers to a creature—a "changeling"—left by fairies in place of a human child. Due to the word's association with the supernatural, Straczynski intended it only as a temporary title, believing he would be able to change it later on.[25]

Casting

[edit]

The filmmakers retained the names of the real-life protagonists, though several supporting characters were composites of people and types of people from the era.[24] Angelina Jolie plays Christine Collins; five actresses campaigned for the role,[9] including Reese Witherspoon and Hilary Swank.[29] Howard and Grazer suggested Jolie; Eastwood agreed, believing that her face fit the period setting.[28][30] Jolie joined the production in March 2007.[31] She was initially reluctant because, as a mother, she found the subject matter distressing.[32] She said she was persuaded by Eastwood's involvement,[10] and the screenplay's depiction of Collins as someone who recovered from adversity and had the strength to fight the odds.[24] Jolie found playing Collins very emotional. She said the most difficult part was relating to the character, because Collins was relatively passive. Jolie ultimately based her performance on her own mother, who died in 2007.[33] For scenes at the telephone exchange, Jolie learned to roller skate in high heels, a documented practice of the period.[24]

Jeffrey Donovan portrays Captain J. J. Jones, a character Donovan became fascinated with because of the power Jones wielded in the city. The character quotes the real Jones' public statements throughout the film, including the scene in which he has Collins committed.[24] Donovan's decision to play Jones with a slight Irish accent was his own.[10] John Malkovich joined the production in October 2007 as Reverend Gustav Briegleb.[34] Eastwood cast Malkovich against type as he felt this would bring "a different shading" to the character.[35] Jason Butler Harner plays Gordon Stewart Northcott, whom Harner described as "a horrible, horrible, wonderful person".[36] He said Northcott believes he shares a connection with Collins due to their both being in the headlines: "In his eyes, they're kindred spirits."[24] Harner landed the role after one taped audition. Casting director Ellen Chenoweth explained that Eastwood chose Harner over more well-known actors who wanted the part because Harner displayed "more depth and variety" and was able to project "a slight craziness" without evoking Charles Manson.[37] Eastwood was surprised by the resemblance between Northcott and Harner, saying they looked "very much" alike when Harner was in makeup.[24]

As Harner did for the Northcott role, Amy Ryan auditioned via tape for the role of Carol Dexter.[38] She cited the filming of a fight scene during which Eastwood showed her "how to throw a movie punch" as her favorite moment of the production.[39] Michael Kelly portrays Detective Lester Ybarra, who is a composite of several people from the historical record.[24] Kelly was chosen based on a taped audition; he worked around scheduling conflicts with the television series Generation Kill, which he was filming in Africa at the same time.[40] Geoff Pierson plays Sammy Hahn, a defense attorney known for taking high-profile cases. He represents Collins and in doing so plants the seeds for overturning "Code 12" internments, used by police to jail or commit those deemed difficult or an inconvenience. Code 12 was often used to commit women without due process. Colm Feore portrays Chief of Police James E. Davis, whose backstory was changed from that of his historical counterpart. Reed Birney plays Mayor George E. Cryer; Denis O'Hare plays composite character Doctor Jonathan Steele; Gattlin Griffith plays Walter Collins; and Devon Conti plays his supplanter, Arthur Hutchins. Eddie Alderson plays Northcott's nephew and accomplice, Sanford Clark.[24]

Filming

[edit]Locations and design

[edit]

James J. Murakami supervised the production design. Location scouting revealed that many of the older buildings in Los Angeles had been torn down, including the entire neighborhood where Collins lived. Suburban areas in San Dimas, San Bernardino and Pasadena doubled for 1920s Los Angeles instead. The Old Town district of San Dimas stood in for Collins' neighborhood and some adjacent locales. Murakami said Old Town was chosen because very little had changed since the 1920s. It was used for interiors and exteriors; the crew decorated the area with a subdued color palette to evoke feelings of comfort.[24] For some exterior shots they renovated derelict properties in neighborhoods of Los Angeles that still possessed 1920s architecture.[42] The crew staged the third floor of the Park Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles into a replica of the 1920s Los Angeles City Council chambers.[43]

The 1918 Santa Fe Depot in San Bernardino doubled for the site of Collins' reunion with "Walter".[44] The production filmed scenes set at San Quentin in the community.[10] A small farm on the outskirts of Lancaster, California, stood in for the Wineville chicken ranch. The crew recreated the entire ranch, referencing archive newspaper photographs and visits to the original ranch to get a feel for the topography and layout.[24] Steve Lech, president of the Riverside Historical Society, was employed as a consultant and accompanied the crew on its visits.[6]

The production sourced around 150 vintage motor cars, dating from 1918 to 1928, from collectors throughout Southern California. In some cases the cars were in too good a condition, so the crew modified them to make the cars appear like they were in everyday use; they sprayed dust and water onto the bodywork and to "age" some of the cars they applied a coating that simulated rust and scratches.[45] The visual effects team retouched shots of Los Angeles City Hall—on which construction was completed in 1928—to remove weathering and newer surrounding architecture.[24] Costume designer Deborah Hopper researched old Sears department store catalogs, back issues of Life magazine and high-school yearbooks to ensure the costumes were historically accurate.[46] Hopper sourced 1920s clothing for up to 1,000 people; this was difficult because the fabrics of the period were not resilient. She found sharp wool suits for the police officers. The style for women of all classes was to dress to create a boyish silhouette, using dropped waist dresses, cloche hats that complemented bob cut hairstyles, fur-trimmed coats and knitted gloves.[24] Jolie said the costumes her Collins character wore formed an integral part of her approach to the character. Hopper consulted historians and researched archive footage of Collins to replicate her look. Hopper dressed Jolie in austere grays and browns with knitted gloves, wool serge skirts accompanying cotton blouses, Mary Jane shoes, crocheted corsages and Art Deco jewelry.[46] In the 1930s sequences at the end of the film, Jolie's costumes become more shapely and feminine, with a decorative stitching around the waistline that was popular to the era.[47]

Principal photography

[edit]Principal photography began on October 15, 2007,[48] finishing two days ahead of its 45-day schedule on December 14, 2007.[10] Universal Pictures provided a budget of $55 million.[49][50] The film was Eastwood's first for a studio other than Warner Bros. since Absolute Power (1997).[51] Filming mainly took place on the Universal Studios backlot in Los Angeles.[52] The backlot's New York Street and Tenement Street depicted downtown Los Angeles. Tenement Street also stood in for the exterior of Northcott's sister's Vancouver apartment; visual effects added the city to the background.[10] The production also used the Warner Bros. backlot in Burbank, California.[53]

Eastwood had clear childhood memories of 1930s Los Angeles and attempted to recreate several details in the film: the town hall, at the time one of the tallest buildings in the city; the city center, which was one of the busiest in the world; and the "perfectly functioning" Pacific Electric Railway, the distinctive red streetcars of which feature closely in two scenes.[21] The production used two functioning replica streetcars for these shots,[41] with visual effects employed for streetcars in the background.[24]

"One day we were shooting a scene where [Collins and Briegleb] talk about her case ... We started shooting at 9:30 am and it was seven or eight pages, which is usually an 18-hour day. Around 2:30, [Eastwood] goes, 'That's lunch and that's a wrap.' ... I've made close to 100 films now and that's certainly a phrase I've never heard in my entire life."

Eastwood is known for his economical film shoots;[54] his regular camera operator, Steve Campanelli, indicated the rapid pace at which Eastwood films—and his intimate, near-wordless direction—also featured during Changeling's shoot.[55] Eastwood limited rehearsals and takes to garner more authentic performances.[24] Jolie said, "You've got to get your stuff together and get ready because he doesn't linger ... He expects people to come prepared and get on with their work."[56] Campanelli sometimes had to tell Jolie what Eastwood wanted from a scene, as Eastwood talked too softly.[55] To provide verisimilitude to certain scenes, Eastwood sometimes asked Jolie to play them quietly, as if just for him. At the same time he would ask his camera operator to start filming discreetly, without Jolie's seeing it.[21]

Malkovich noted Eastwood's direction as "redefining economical", saying Eastwood was quiet and did not use the phrases "action" and "cut". He said, "Some [directors]—like Clint Eastwood or Woody Allen—don't really like to be tortured by a million questions. They hire you, and they figure you know what to do and you should do it ... And that's fine by me."[57] Ryan also noted the calmness of the set,[58] observing that her experiences working with director Sidney Lumet on 100 Centre Street and Before the Devil Knows You're Dead were useful due to his sharing Eastwood's preference for filming a small number of takes.[38][59]

Donovan said Eastwood seldom gave him direction other than to "go ahead", and that Eastwood did not even comment on his decision to play Jones with a slight Irish accent: "Actors are insecure and they want praise, but he's not there to praise you or make you feel better ... All he's there to do is tell the story and he hired actors to tell their story."[10] Gaffer Ross Dunkerley said he often had to work on a scene without having seen a rehearsal: "Chances are we'll talk about it for a minute or two and then we're executing it."[43]

The original edit was almost three hours long; to hone it to 141 minutes, Eastwood cut material from the first part of the film to get to Collins' story sooner. To improve the pacing he also cut scenes that focused on Reverend Briegleb.[22] Eastwood deliberately left the ending of the film ambiguous to reflect the uncertain fates of several characters in the history. He said that while some stories aimed to finish at the end of a film, he preferred to leave it open-ended.[21]

Cinematography

[edit]Changeling was director of photography Tom Stern's sixth film with Eastwood.[43] Despite the muted palette, the film is more colorful than some previous Stern–Eastwood collaborations. Stern referenced a large book of period images. He attempted to evoke Conrad Hall's work on Depression-set film The Day of the Locust, as well as match what he called the "leanness" of Mystic River's look. Stern said the challenge was to make Changeling as simple as possible to shoot. To focus more on Jolie's performance, he tended to avoid the use of fill lighting.[43] Eastwood did not want the flashbacks to Northcott's ranch to be too much like a horror film—he said the focus of the scene was the effect of the crimes on Sanford Clark—so he avoided graphic imagery in favor of casting the murders in shadow.[60]

Stern shot Changeling in anamorphic format on 35mm film using Kodak Vision 500T 5279 film stock. The film was shot on Panavision cameras and C-Series lenses. Due to the large number of sets, the lighting rigs were more extensive than on other Eastwood productions. The crew made several ceilings from bleached muslin tiles. Stern lit the tiles from above to produce a soft, warm light that was intended to evoke the period through tones close to antique and sepia. The crew segregated the tiles using fire safety fabric Duvatyn to prevent light spilling onto neighboring clusters. The key light was generally softer to match the warm tones given off by the toplights. Stern used stronger skypans—more intense than is commonly used for key lighting—to reduce contrasts when applying daytime rain effects, as a single light source tended to produce harder shadows.[43]

Stern lit scenes filmed at the Park Plaza Hotel using dimmable HMI and tungsten lights rigged within balloon lights. This setup allowed him to "dial in" the color he wanted, as the blend of tones from the tungsten fixtures, wooden walls and natural daylight made it difficult to illuminate the scenes using HMIs or daylight exclusively. Stern said the period setting had little effect overall on his lighting choices because the look was mostly applied in the production design and during digital intermediate (DI), the post-production digital manipulation of color and lighting. Technicolor Digital Intermediates carried out the DI. Stern supervised most of the work via e-mailed reference images as he was in Russia shooting another film at the time. He was present at the laboratory for the application of the finishing touches.[43]

Visual effects

[edit]Overview

[edit]

CIS Vancouver and Pac Title created most of the visual effects, under the overall supervision of Michael Owens. CIS' work was headed by Geoff Hancock and Pac Title's by Mark Freund. Each studio created around 90 shots. Pac Title focused primarily on 2D imagery;[52] VICON House of Moves handled the motion capture.[61] The effects work consisted mainly of peripheral additions: architecture, vehicles, crowds and furniture.[52][62] CIS used 3D modeling package Maya to animate city scenes before rendering them in mental ray; they generated matte paintings in Softimage XSI and Maya and used Digital Fusion for some 2D shots. The team's work began with research into 1928 Los Angeles; they referenced historical photographs and data on the urban core's population density.[52] CIS had to generate mostly new computer models, textures and motion capture because the company's existing effects catalog consisted primarily of modern era elements.[62] CIS supplemented exteriors with skylines and detailed backdrops.[24] They created set extensions digitally and with matte paintings.[62] CIS created city blocks by using shared elements of period architecture that could be combined, rearranged and restacked to make buildings of different widths and heights; that way, the city could look diverse with a minimum of textural variation. CIS referenced vintage aerial photographs of downtown Los Angeles so shots would better reflect the geography of the city, as Hancock felt it important to have a consistency that would allow audiences to understand and become immersed in the environment.[52]

To maintain the rapid shooting pace Eastwood demanded, Owens chose to mostly avoid using bluescreen technology, as the process can be time-consuming and difficult to light. He instead used rotoscoping, the process whereby effects are drawn directly onto live action shots.[62] Rotoscoping is more expensive than bluescreen, but the technique had proved reliable for Eastwood when he made extensive use of it on Flags of Our Fathers (2006) to avoid shooting against bluescreen on a mountaintop. For Owens, the lighting was better, and he considered rotoscoping to be "faster, easier and more natural".[52] Owens used bluescreen in only a few locations, such as at the ends of backlot streets where it would not impact the lighting.[62] The Universal Studios backlot had been used for so many films that Owens thought it important to disguise familiar architecture as much as possible, so some foreground and middle distance buildings were swapped. One of his favorite effects shots was a scene in which Collins exits a taxi in front of the police station. The scene was filmed almost entirely against bluescreen; only Jolie, the sidewalk, the taxi cab and an extra were real. The completed shot features the full range of effects techniques used in the film: digital extras in the foreground, set extensions and computer-generated vehicles.[52]

Digital extras

[edit]For crowd scenes, CIS supplemented the live-action extras with digital pedestrians created using motion capture.[52] House of Moves captured the movements of five men and four women during a two-day shoot supervised by Hancock.[61] The motion capture performers were coached to make the "small, formal and refined" movements that Owens said reflected the general public's conduct at the time.[52][62] CIS combined the motion data with the Massive software package to generate the interactions of the digital pedestrians. The use of Massive presented a challenge when it came to blending digital pedestrians with live-action extras who had to move from the foreground into the digital crowd.[62] Massive worked well until this stage, when the effects team had to move the digital pedestrians to avoid taking the live-action extras out of the shot.[52] To allow close-ups of individual Massive extras, the effects team focused on their faces and walking characteristics. Hancock explained, "We wanted to be able to push Massive right up to the camera and see how well it held up. In a couple of shots the characters might be 40 feet away from the camera, about 1⁄5 screen height. The bigger the screen is, the bigger the character. He could be 10 feet tall, so everything, even his hair, better look good!"[62] Typically, a limited number of motion performances are captured and Massive is used to create further variety, such as in height and walking speed. Because the digital extras were required to be close to the foreground,[61] and to integrate them properly with the live action extras, House of Moves captured twice as much motion data than CIS had used on any other project.[52] CIS created nine distinct digital characters. To eliminate inaccuracies that develop when creating a digital extra of different proportions to the motion capture performer, CIS sent nine skeleton rigs to House of Moves before work began. This gave House of Moves time to properly adapt the rigs to its performers, resulting in motion capture data that required very little editing in Massive.[61] CIS wrote shaders for their clothing; displacement maps in the air shader were linked with the motion capture to animate wrinkles in trousers and jackets.[52]

Closing sequence

[edit]

Forgoing the closure favored by its contemporaries, Changeling's final sequence reflects Collins' renewed hope that Walter is alive.[62][63] The shot is a two-and-a-half-minute sequence showing Collins' walking off to become lost in a crowd.[62] The sequence is representative of the range of effects that feature throughout the film; Los Angeles itself is presented as a major character,[52] brought to life by unobtrusive peripheral imagery that allows the viewer to focus on the story and the emotional cues. The "hustle and bustle" of the sequence was required to convey that downtown Los Angeles in 1935 was a congested urban center. In the closing shot, the camera tilts up to reveal miles of city blocks,[62] pedestrians on the streets, cars going by and streetcars running along their tracks.[52] The version of the film that screened at Cannes did not include this sequence; the scene faded to black as Collins walked away. The new 4,000-frame shot was Owens' idea. He felt the abrupt cut to black pulled the viewer out of the film too quickly, and that it left no room for emotional reflection. Owens said, "There is a legend at the end before the credits. The legend speaks to what happened after the fact, and I think you need to just swallow that for a few moments with the visual still with you." Owens told Eastwood the film should end like Chinatown (1974), in which the camera lifts to take in the scene: "The camera booms up and she walks away from us from a very emotional, poignant scene at the end, walks away into this mass of people and traffic. It's very hopeful and sad at the same time."[62]

Owens did not have time to complete the shot before the Cannes screenings, but afterwards he used cineSync to conduct most of the work from home. The shot includes two blocks of computer-generated buildings that recede into the distance of a downtown set extension. As Collins disappears into the crowd about a minute into the shot, the live footage is gradually joined with more digital work.[62] The streetcars, tracks and power lines were all computer generated. Live-action extras appear for the first minute of the shot before being replaced by digital ones. The shot was made more complicated by the need to add Massive extras.[52] Owens constructed the scene by first building the digital foreground around the live action footage. He then added the background before filling the scene with vehicles and people.[62]

Music

[edit]Eastwood composed Changeling's jazz-influenced score. Featuring lilting guitars and strings, it remains largely low-key throughout. The introduction of brass instruments evokes film noir, playing to the film's setting in a city controlled by corrupt police. The theme shifts from piano to a full orchestra, and as the story develops, the strings become more imposing, with an increasing number of sustains and rises. Eastwood introduces voices reminiscent of those in a horror film score during the child murder flashbacks.[64][65] The score was orchestrated and conducted by Lennie Niehaus.[66] It was released on CD in North America on November 4, 2008, through record label Varèse Sarabande.[67]

Themes

[edit]Disempowerment of women

[edit]Changeling begins with an abduction, but largely avoids framing the story as a family drama to concentrate on a portrait of a woman whose desire for independence is seen as a threat to male-dominated society.[21][68] The film depicts 1920s Los Angeles as a city in which the judgment of men takes precedence; women are labeled "hysterical and unreliable" if they dare to question it.[69] Rather than "an expression of feminist awareness", David Denby argues, the film—like Eastwood's Million Dollar Baby—is "a case of awed respect for a woman who was strong and enduring".[70] The portrait of a vulnerable woman whose mental state is manipulated by the authorities was likened to the treatment of Ingrid Bergman's character in Gaslight (1944), who also wondered if she might be insane;[21][71] Eastwood cited photographs that show Collins smiling with the child she knows is not hers.[21] Like many other women of the period who were deemed disruptive, Collins is forced into the secret custody of a mental institution. The film shows that psychiatry became a tool in the gender politics of the era, only a few years after women's suffrage in the United States was guaranteed by the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. As women ceased to be second-class citizens and began to assert their independence, the male establishment used mental institutions in an effort to disempower them; in common with other unmanageable women, Collins is subjected to medical treatment designed to break her spirit and compel obedience, though some of the treatments, specifically the electroconvulsive therapy depicted in the film, did not exist ca. 1928–1930. The film quotes the testimony of the psychiatrist who treated Collins. Eastwood said the testimony evidenced how women were prejudged and that the behavior of the police reflected how women were seen at the time. He quoted the words of the officer who sent Collins to the mental facility: "'Something is wrong with you. You're an independent woman.'" Clint Eastwood said, "The period could not accept [it]".[21]

Corruption in political hierarchies

[edit]Romantic notions of the 1920s as a more innocent period are put aside in favor of depicting Los Angeles as ruled by a despotic political infrastructure, steeped in sadistic, systematic corruption throughout the city government, police force and medical establishment.[24][69][72] In addition to being a Kafkaesque drama about the search for a missing child,[63][73] the film also focuses on issues relevant to the modern era.[74] Eastwood noted a correlation between the corruption of 1920s Los Angeles and that of the modern era, manifesting in the egos of a police force that thinks it cannot be wrong and the way in which powerful organizations justify the use of corruption.[75] "[The] Los Angeles police department every so often seems to go into a period of corruption," he said, "It's happened even in recent years ... so it was nice to comment [on that] by going back to real events in 1928."[74] Eastwood said that Los Angeles had always been seen as "glamorous",[60] but he believed there had never been a "golden age" in the city.[21] In Changeling, this dissonance manifests in the actions of Arthur Hutchins, who travels to the city in the hope of meeting his favorite actor. Eastwood said that given the corruption that the story covers, Hutchins' naïveté seemed "bizarre".[60] As a lesson in democratic activism, the film shows what it takes to provoke people to speak against unchecked authority, no matter the consequences. Richard Brody of The New Yorker said this rang as true for 1928 Los Angeles as it did for Poland in 1980 or Pakistan in 2008.[76] The film directly quotes chief of police James E. Davis: "We will hold trial on gunmen in the streets of Los Angeles. I want them brought in dead, not alive, and I will reprimand any officer who shows the least bit of mercy to a criminal."[24]

Children and violence

[edit]Changeling sits with other late-period Eastwood films in which parenting—and the search for family—is a theme. It makes literal the parental struggle to communicate with children. It can also be seen as a variation of the Eastwood "revenge movie" ethic; in this case, the "avenging grunt" transforms into a courteous woman who only once makes a foul-mouthed outburst.[73] Eastwood dealt with themes of child endangerment in A Perfect World (1993) and Mystic River (2003).[77] Changeling is a thematic companion piece to Mystic River,[21][78] which also depicted a community contaminated by an isolated, violent act against a child—a comparison with which Eastwood agreed.[21] He said that showing a child in danger was "about the highest form of drama you can have", as crimes against them were to him the most horrible.[77] Eastwood explained that crimes against children represented a theft of lives and innocence.[60] He said, "When [a crime] comes along quite as big as this one, you question humanity. It never ceases to surprise me how cruel humanity can be."[77] Samuel Blumenfeld of Le Monde said the scene featuring Northcott's execution by hanging was "unbearable" due to its attention to detail; he believed it one of the most convincing pleas against the death penalty imaginable. Eastwood noted that for a supporter of capital punishment, Northcott was an ideal candidate and that in a perfect world the death penalty might be an appropriate punishment for such a crime.[21] He said that crimes against children would be at the top of his list for justifications of capital punishment,[9] but that whether one were pro- or anti-capital punishment, the barbarism of public executions must be recognized. Eastwood argued that in putting the guilty party before his victims' families, justice may be done, but after such a spectacle the family would find it hard to find peace. The scene's realism was deliberate: the audience hears Northcott's neck breaking, his body swings and his feet shake. It was Eastwood's intention to make it unbearable to watch.[21]

Release

[edit]Strategy

[edit]

Changeling premiered in competition at the 61st Cannes Film Festival on May 20, 2008.[79] The film was Eastwood's fifth to enter competition at the festival.[80] Its appearance was not part of the original release plan. Universal executives had been looking forward to the festival without the worry associated with screening a film, until Eastwood made arrangements for Changeling's appearance.[81] He was pleased with the critical and commercial success that followed Mystic River's appearance at the festival in 2003 and wanted to generate the same "positive buzz" for Changeling.[29] The film was still in post-production one week before the start of the festival.[81] It appeared at the 34th Deauville American Film Festival, held September 5–14, 2008,[82] and had its North American premiere on October 4, 2008, as the centerpiece of the 46th New York Film Festival, screening at the Ziegfeld Theatre.[83]

The producers and Universal considered opening Changeling wide in its first weekend to capitalize on Jolie's perceived box office appeal, but they ultimately modeled the release plan after those of other Eastwood-directed films, Mystic River in particular. While the usual strategy is to open films by notable directors in every major city in the United States to ensure a large opening gross, in what the industry calls a "platform release", Eastwood's films generally open in a small number of theaters before opening wide a week later.[29] Changeling was released in 15 theaters[Note 2] in nine markets in the United States on October 24, 2008.[84] The marketing strategy involved trailers that promoted Eastwood's involvement and the more commercial mystery thriller elements of the story. Universal hoped the limited release would capitalize on good word-of-mouth support from "serious movie fans" rather than those in the 18–25-year-old demographic.[29] The film was released across North America on October 31, 2008, playing at 1,850 theaters,[85] expanding to 1,896 theaters by its fourth week.[86] Changeling was released in the United Kingdom on November 26, 2008,[87] in Ireland on November 28, 2008,[88] and in Australia on February 5, 2009.[89]

Box office

[edit]

Changeling performed modestly at the box office,[90] grossing more internationally than in North America.[91][92] The worldwide gross revenue was $113 million.[49] The film's limited American release saw it take $502,000—$33,441 per theater—in its first two days.[84] Exit polling showed strong commercial potential across a range of audiences.[93] CinemaScore polls conducted during the opening weekend revealed the average grade cinemagoers gave Changeling was A− on an A+ to F scale.[94] Audiences were mostly older; 68% were over 30 and 61% were women.[95] Audience evaluations of "excellent" and "definitely recommended" were above average. The main reasons given for seeing the film were its story (65%), Jolie (53%), Eastwood (43%) and that it was based on fact (42%).[93] The film made $2.3 million in its first day of wide release,[85] going on to take fourth place in the weekend box office chart with $9.4 million—a per-theater average of $5,085.[95] This return surpassed Universal's expectations for the weekend.[93] Changeling's link to the Inland Empire—the locale of the Wineville killings—generated additional local interest, causing it to outperform the national box office by 45% in its opening weekend.[96][Note 3] The film surpassed expectations in its second weekend of wide release,[97] declining 22% to take $7.3M.[98] By the fourth week, Changeling had dropped to fifth place at the box office, having taken $27.6M overall.[99] In its sixth week the number of theaters narrowed to 1,010,[100] and Changeling dropped out of the national top ten, though it remained in ninth place on the Inland chart.[101][Note 4] Changeling completed its theatrical run in North America on January 8, 2009, having earned $35.7 million overall.[49]

Changeling made its international debut in four European markets on November 12–14, 2008,[102] opening in 727 theaters to strong results.[103] Aided by a positive critical reaction, the film took $1.6 million in Italy from 299 theaters (a per-location average of $5,402),[104] and $209,000 from 33 screens in Belgium.[105] Changeling had a slower start in France, but improved to post $2.8 million from 417 theaters in its first five days,[104] and finished the weekend in second place at the box office.[105] The second week in France saw the box office drop by just 27%, for a total gross of $5.4 million.[106] By November 23, 2008, the film had taken $8.6 million outside North America.[107] The weekend of November 28–30 saw Changeling take $4.4 million from 1,040 theaters internationally;[108] this included its expansion into the United Kingdom, where it opened in third place at the box office, taking $1.9 million from 349 theaters.[109] It took $1.5 million from the three-day weekend, but the total was boosted by the film's opening two days earlier to avoid competition from previews of Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa.[110] The return marked the best opening of any Eastwood-directed film in the United Kingdom to that point.[109] Its second week of release in the United Kingdom saw a drop of 27% to $1.1 million.[111] Changeling earned $7.6 million in Ireland and the United Kingdom.[102]

Changeling's release in other European markets continued throughout December 2008.[112][113] By December 8, the film had opened in 1,167 theaters in nine markets for an international gross of $19.1 million.[113][114] Changeling's next significant international release came in Spain on December 19, 2008,[114] where it opened in first place at the box office with $2 million from 326 theaters. This figure marked the best opening for an Eastwood-directed film in the country to that point;[115] after six weeks it had earned $11 million. In January 2009, major markets in which the film opened included Germany, South Korea and Russia. In Germany, it opened in ninth place at the box office with $675,000 from 194 theaters. South Korea saw a "solid" opening of $450,000 from 155 theaters.[116] In Russia, it opened in eighth place with $292,000 from 95 theaters.[117] By January 26, 2009, the film had taken $47.2 million from 1,352 international theaters.[116] Aided by strong word-of-mouth support, Changeling's Australian release yielded $3.8M from 74 screens after eight weeks.[118] The film opened in Japan on February 20, 2009,[102] where it topped the chart in its first week with $2.4 million from 301 screens.[119] After six weeks, it had earned $12.8 million in the country.[120] The film's last major market release was in Mexico on February 27, 2009,[119] where it earned $1.4 million. The international gross was $77.3 million.[102]

Home media

[edit]Changeling was released on Blu-ray Disc, DVD and Video on demand in North America on February 17, 2009,[121][122] and in the United Kingdom on March 30, 2009.[123] After its first week of release, Changeling placed fourth in the DVD sales chart with 281,000 units sold for $4.6 million;[124] by its fourth week of release, the film had dropped out of the top 10, having earned $10.1 million.[122] As of the latest figures, 762,000 units have been sold, translating to $12,638,223 in revenue.[122] The DVD release included two featurettes: Partners in Crime: Clint Eastwood and Angelina Jolie and The Common Thread: Angelina Jolie Becomes Christine Collins. The Blu-ray Disc release included two additional features: Archives and Los Angeles: Then and Now.[125]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]

The film's screening at Cannes met with critical acclaim, prompting speculation it could be awarded the Palme d'Or.[22][126] The award eventually went to Entre les murs (The Class).[127] Straczynski claimed that Changeling's loss by two votes was due to the judges' not believing the story was based on fact. He said they did not believe the police would treat someone as they had Collins. The loss led to Universal's request that Straczynski annotate the script with sources.[22] Although the positive critical notices from Cannes generated speculation that the film would be a serious contender at the 2009 Academy Awards, the North American theatrical release met with a more mixed response.[128][129] As of June 2020[update], the film holds a 62% approval rating on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, based on 210 critical reviews, with an average rating of 6.3/10. The website's critical consensus states, "Beautifully shot and well-acted, Changeling is a compelling story that unfortunately gives in to convention too often."[130] Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average rating to reviews from mainstream critics, reported a score of 63 out of 100 based on 38 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[131] The film's reception in several European countries was more favorable,[104][132] and in the United Kingdom 83% of critics listed by Rotten Tomatoes gave Changeling positive reviews.[133]

Todd McCarthy of Variety said Jolie was more affecting than in A Mighty Heart (2007) because she relied less on artifice. He also noted a surfeit of good supporting performances, Michael Kelly's in particular.[78] Oliver Séguret of Libération said the cast was the film's best feature. He praised the supporting actors and said Jolie's performance was forceful yet understated.[68] Kirk Honeycutt of The Hollywood Reporter said Jolie shunned her "movie star" persona to appear vulnerable and resolute. He perceived the supporting characters—Amy Ryan's excepted—as having few shades of gray.[69] David Ansen, writing in Newsweek, echoed the sentiment, but said that "some stories really are about the good guys and the bad". He said that with the distractions of Jolie's celebrity and beauty put aside, she carried the role with restraint and intensity.[134] Manohla Dargis of The New York Times felt that Jolie's celebrity was distracting enough to render her unconvincing,[135] and David Denby of The New Yorker said that, while Jolie showed skill and selflessness, the performance and character were uninteresting; he said Collins was one-dimensional, lacking desires or temperament. He cited similar problems with Malkovich's Briegleb, concluding, "The two of them make a very proper and dull pair of collaborators."[136]

"Jolie puts on a powerful emotional display as a tenacious woman who gathers strength from the forces that oppose her. She reminds us that there is nothing so fierce as a mother protecting her cub."

McCarthy admired the "outstanding" script, calling it ambitious and deceptively simple. He said Eastwood respected the script by not playing to the melodramatic aspects and not telegraphing the story's scope from the start.[78] Honeycutt wrote that due to its close adherence to the history the drama sagged at one point, but that the film did not feel as long as its 141 minutes because the filmmakers were "good at cutting to the chase".[69] Ansen said Straczynski's dialogue tended to the obvious, but that while the film lacked the moral nuance of Eastwood's others, the well-researched screenplay was "a model of sturdy architecture", each layer of which built audience disgust into a "fine fury". He said, "when the tale is this gripping, why resist the moral outrage?"[134]

Séguret said the film presented a solid recreation of the era, but that Eastwood did not seem inspired by the challenge. Séguret noted that Eastwood kept the embers of the story alight, but that it seldom burst into flames. He likened the experience to being in a luxury car: comfortable yet boring.[68] Denby and Ansen commented that Eastwood left the worst atrocities to audiences' imaginations. Ansen said this was because Eastwood was less interested in the lurid aspects of the case.[134] McCarthy praised the thoughtful, unsensationalized treatment,[78] while Denby cited problems with the austere approach, saying it left the film "both impressive and monotonous". He said Eastwood was presented with the problem of not wanting to exploit the "gruesome" material because this would contrast poorly with the delicate emotions of a woman's longing for her missing son. Denby said Eastwood and Straczynski should have explored more deeply the story's perverse aspects. Instead, he said, the narrative methodically settled the emotional and dramatic issues—"reverently chronicling Christine's apotheosis"—before "[ambling] on for another forty minutes".[136] Ansen said the classical approach lifted the story to another level and that it embraced horror film conventions only in the process of transcending them.[134] McCarthy said Changeling was one of Eastwood's most vividly realized films, noting Stern's cinematography, the set and costume design, and CGI landscapes that merged seamlessly with location shots.[78] Dargis was not impressed by the production design; she cited the loss of Eastwood's regular collaborator Henry Bumstead—who died in 2006—as a factor in Changeling's "overly pristine" look.[135]

"J. Michael Straczynski's disjointed script manages to ring false at almost every significant turn ... and Clint Eastwood's ponderous direction—a disheartening departure from his sure touch in 'Letters From Iwo Jima' and 'The Bridges of Madison County'—magnifies the flaws."

Damon Wise of Empire called Changeling "flawless",[138] and McCarthy said it was "emotionally powerful and stylistically sure-handed". He stated that Changeling was a more complex and wide-ranging work than Eastwood's Mystic River, saying the characters and social commentary were brought into the story with an "almost breathtaking deliberation". He said that as "a sorrowful critique of the city's political culture", Changeling sat in the company of films such as Chinatown and L.A. Confidential.[78] Honeycutt said the film added a "forgotten chapter to the L.A. noir" of those films and that Eastwood's melodic score contributed to an evocation of a city and a period "undergoing galvanic changes". Honeycutt said, "[the] small-town feel to the street and sets ... captures a society resistant to seeing what is really going on".[69] Séguret said that while Changeling had few defects, it was mystifying that other critics had such effusive praise for it.[68] Denby said it was beautifully made, but that it shared the chief fault of other "righteously indignant" films in congratulating the audience for feeling contempt for the "long-discredited" attitudes depicted.[136] Ansen concluded that the story was told in such a sure manner that only a hardened cynic would be left unmoved by the "haunting, sorrowful saga".[134]

Awards and honors

[edit]In addition to the following list of awards and nominations, the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures named Changeling one of the 10 best films of 2008,[139] as did the International Press Academy, which presents the annual Satellite Awards.[140] Several critics included the film on their lists of the top 10 best films of 2008. Anthony Lane of The New Yorker named it second best, Empire magazine named it fourth best and Rene Rodriguez of The Miami Herald named it joint fourth best with Eastwood's Gran Torino.[141] Japanese film critic Shigehiko Hasumi listed the film as one of the best films of 2000–2009.[142]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Straczynski described 95% of the script as being drawn from around 6,000 pages of documentation.

- ^ The theater count refers to individual movie theaters that may include multiple auditoriums. The screen count refers to individual auditoriums.

- ^ Changeling took $117,862 in 16 Inland Empire theaters, for an average of $7,366 per location.

- ^ In the film's sixth week of release in the Inland Empire, it earned $20,540 on 14 screens.

References

[edit]- ^ "Changeling". Turner Classic Movies. Atlanta: Turner Broadcasting System (Time Warner). Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ Straczynski, J. Michael (2019). Becoming Superman. HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 227–228.

- ^ Straczynski, J. Michael (2019). Becoming Superman. HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 382–394.

- ^ "Changeling". BoxOfficeMojo.com. Archived from the original on June 1, 2009.

- ^ Flacco, Anthony (2009). The Road Out of Hell: Sanford Clark and the True Story of the Wineville Murders. Clark, Jerry. Union Square Press. ISBN 978-1-4027-6869-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Stokley, Sandra (October 30, 2008). "Riverside County 'chicken coop murders' inspire Clint Eastwood movie, new book". The Press-Enterprise. A. H. Belo Corporation. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ^ a b c Sacha Howells (November 7, 2008). "Spoilers: Changeling – The Real Story Behind Eastwood's Movie". film.com. RealNetworks. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- ^ Rasmussen, Cecilia (February 7, 1999). "The Boy Who Vanished—and His Impostor". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Abramowitz, Rachel (October 18, 2008). "'Changeling' revisits a crime that riveted L.A." Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2008. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Longwell, Todd (November 20, 2008). "United for 'Changeling'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2008. (registration required for online access)

- ^ a b c d Neuman, Clayton (May 20, 2008). "Cannes Film Festival – Interview With Changeling Screenwriter J. Michael Straczynski". American Movie Classics. Rainbow Media. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Eberson, Sharon (August 9, 2007). "Busy writer is drawn back to 23rd century". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gotshalk, Shira. "The Phenom". wga.org. Writers Guild of America West. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ^ Straczynski, J. Michael (1996). The Complete Book of Scriptwriting (Revised ed.). Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer's Digest Books. p. 165. ISBN 0-89879-512-5.

- ^ a b c Gnerre, Andrew (October 24, 2008). "Times Are Changing for J. Michael Straczynski". MovieMaker. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2008.

- ^ Snyder, Gabriel (June 27, 2006). "U picks up 'Changeling'". Variety. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ^ Garrett, Diane; Fleming, Michael (March 8, 2007). "Eastwood, Jolie catch 'Changeling'". Variety. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ Fernandez, Jay (October 11, 2006). "The Big Name Gets Distracted". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved January 30, 2008. (registration required for online access)

- ^ Straczynski, J. Michael (October 11, 2006). "Re: Ron Howard's Changeling project falls through?". Newsgroup: rec.arts.sf.tv.babylon5.moderated. Usenet: 1160616893.068094.9610@i42g2000cwa.googlegroups.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ^ Clint Eastwood (February 17, 2009). Partners In Crime: Clint Eastwood and Angelina Jolie (DVD featurette). Universal Studios. Event occurs at 1:15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Blumenfeld, Samuel (May 16, 2008). "Clint Eastwood, dans les ténèbres de Los Angeles". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved June 12, 2008. (registration required for online access)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Davis, Jason (September–October 2008). "How Changeling Changed J. Michael Straczynski". Creative Screenwriting Magazine. 15 (5). Creative Screenwriters Group: 18–21. ISSN 1084-8665.

- ^ Blair, Elizabeth (October 24, 2008). "Behind 'Changeling,' A Tale Too Strange For Fiction". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved October 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "'Changeling' production notes". universalpicturesawards.com. Universal Pictures. Archived from the original (Microsoft Word document) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ^ a b Cruz, Gilbert (October 23, 2008). "Q&A: Changeling Writer J. Michael Straczynski". Time. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ^ Amaya, Erik (February 24, 2008). "Wondercon: Spotlight on Straczynski". Comic Book Resources. Boiling Point Productions. Archived from the original on January 12, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ Durian, Hal (February 7, 2009). "Hal Durian's Riverside Recollections". The Press-Enterprise. A. H. Belo Corporation. Archived from the original on September 7, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ^ a b Josh Horowitz (June 24, 2008). "Clint Eastwood On 'Changeling' With Angelina Jolie, 'Gran Torino' And Reuniting With Morgan Freeman". mtv.com. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved July 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c d John Horn (October 23, 2008). "'Changeling' banks on the Eastwood effect". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ Eliot, Marc (2009). American Rebel: The Life of Clint Eastwood. Harmony Books. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-307-33688-0.

- ^ Michael Fleming, Diane Garrett (March 19, 2007). "Jolie 'Wanted' for Universal film". Variety. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ^ Staff (February 5, 2009). "People: Penelope Cruz, Ellen DeGeneres, Angelina Jolie". The Dallas Morning News. A. H. Belo Corporation. Archived from the original on June 14, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ Liam Allen (November 21, 2008). "Emotional Jolie takes no prisoners". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- ^ Borys Kit (October 16, 2007). "3 join Jolie for 'Changeling'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2007. (registration required for online access)

- ^ Susan Chenery (August 23, 2008). "Master of Reinvention". The Australian. Archived from the original on August 24, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ Haun, Harry (October 5, 2007). "Playbill on Opening Night: Mauritius—A Threepenny Opera". Playbill. Archived from the original on February 23, 2008. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ^ Lipsky-Karasz, Elisa (October 2008). "Jason Butler Harner: The New York Theater Veteran Takes to the Big Screen with a Frightening Star Turn". W Magazine. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2008.

- ^ a b Brett Johnson (January 27, 2008). "Amy Ryan rides roller coaster of a career". Ventura County Star. E. W. Scripps Company. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ^ Lina Lofaro (January 12, 2008). "Q&A: Amy Ryan". Time. Archived from the original on January 18, 2008. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ^ Susan King (September 7, 2008). "'Changeling' actor reveres his boss: Clint Eastwood". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Clint Eastwood (February 17, 2009). Partners In Crime: Clint Eastwood and Angelina Jolie (DVD featurette). Universal Studios. Event occurs at 12:17.

- ^ Clint Eastwood, Jon Stewart (October 2, 2008). The Daily Show with Jon Stewart (Television production). New York City: Comedy Central. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Heuring, David (November 2008). "Lost and Seemingly Found". American Cinematographer. 89 (11). American Society of Cinematographers: 18–20.

- ^ Soifer, Jerry (May 9, 2009). "Enthusiasts mark National Train Day". The Press-Enterprise. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Day, Patrick Kevin (November 5, 2008). "Scene Stealer: 'Changeling's' vintage autos". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2008. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Wells, Rachel (February 2, 2009). "Changeling your wardrobe". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ Deborah Hopper (February 17, 2009). The Common Thread: Angelina Jolie Becomes Christine Collins (DVD featurette). Universal Studios. Event occurs at 4:03.

- ^ Archerd, Army (September 20, 2007). "Eastwood plots schedule". Variety. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Changeling (2008)". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Archived from the original on June 1, 2009. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ Hughes, Howard (2009). Aim for the Heart. London, England: I.B. Tauris. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- ^ Foundas, Scott (December 19, 2007). "Clint Eastwood: The Set Whisperer". LA Weekly. Village Voice Media. Archived from the original on September 25, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Thomas J. McLean (October 27, 2008). "Changeling: VFX as 'Peripheral Imagery'". VFXWorld. Animation World Network. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^ "Film Details: l' échange (The Exchange)". festival-cannes.com. Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original on July 4, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

- ^ a b Tony Rivetti Jr. (August 22, 2008). "Movie Preview: Changeling". Entertainment Weekly. No. 1007–1008. Archived from the original on October 9, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ a b Glen Schaefer (April 13, 2008). "He makes Clint's day". The Province. Pacific Newspaper Group. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ^ Josh Horowitz (June 18, 2007). "Angelina Jolie Can't Wait To Go Toe-To-Toe with Clint Eastwood". mtv.com. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on February 10, 2008. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ^ Jessica Goebel, Larry Carroll (November 9, 2007). "Malkovich Makes A 'Changeling'". mtv.com. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ Larry Carroll (November 27, 2007). "Amy Ryan Loves Spare 'Changeling'". mtv.com. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ^ Missy Schwartz (November 2007). "Amy Ryan Checks In". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 29, 2007. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Geoff Andrew (September 2008). "Changeling Man". Sight & Sound. 18 (9): 17. ISSN 0037-4806.

- ^ a b c d Thomas J. McLean (November 20, 2008). "VICON House of Moves Provides Mo-Cap for Changeling". VFXWorld. Animation World Network. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Renee Dunlop (November 6, 2008). "Guiding the eye to the Invisible Digital Effects for Changeling". The CG Society. Ballistic Media. Archived from the original on November 9, 2008. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Robert Hanks (November 28, 2008). "Film of the week: Changeling". The Independent. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ Daniel Schweiger (November 25, 2008). "CD Review: Changeling—Original Soundtrack". Film Music Magazine. Global Media Online. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Elizabeth Blair (October 24, 2008). "'Changeling' Another Step In Eastwood's Evolution". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on March 17, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- ^ Changeling Soundtrack (CD liner). Clint Eastwood. Varèse Sarabande. 2008. 3020669342.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "Changeling: Product Details". varesesarabande.com. Varèse Sarabande. Archived from the original on January 5, 2011. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Séguret, Oliver (May 21, 2008). "L'Echange: bon procédé". Libération (in French). Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Honeycutt, Kirk (May 20, 2008). "Film Review: Changeling". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ David Denby (March 8, 2010). "Out of the West". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 7, 2010. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ Scott Feinberg (October 7, 2008). "'Changeling' and Angelina Jolie: Awards are not won on paper". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ Richard Corliss (May 20, 2008). "Clint and Angelina Bring a Changeling Child to Cannes". Time. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Andrew Billen (February 28, 2009). "How Clint Eastwood became a New Man". The Times. London. Retrieved March 2, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ a b Staff (February 27, 2009). "Eastwood given special honour by Cannes". Yahoo News/Australian Associated Press. Retrieved March 2, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Brad Balfour (November 12, 2008). "Clint Eastwood As a Changeling". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on April 5, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ^ Richard Brody (March 9, 2009). "Eastwood Ho!". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 6, 2009. Retrieved March 2, 2009.

- ^ a b c David Germain (May 21, 2008). "Eastwood takes on mother's story; Jolie plays single mom whose child goes missing". The Chronicle Herald. Associated Press.

- ^ a b c d e f McCarthy, Todd (May 20, 2008). "'Changeling' review". Variety. Archived from the original on May 30, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Screenings Guide" (PDF). festivale-cannes.com. Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ Todd McCarthy (April 22, 2008). "Clint's 'Changeling' set for Cannes". Variety. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ^ a b Charles Masters, Scott Roxborough (May 13, 2008). "Cannes' late lineup causes headaches". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2008. (registration required for online access)

- ^ John Hopewell (July 21, 2008). "'Mamma Mia!' opens Deauville: Musical to kick off festival on Sept. 5". Variety. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ^ Gregg Goldstein (August 13, 2008). "New York film fest stocked with Cannes titles". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 11, 2009. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ a b Dade Hayes (October 26, 2008). "'HSM 3' makes box office honor roll". Variety. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ a b Anthony D'Alessandro (November 1, 2008). "'Saw V' scares off B.O. competition". Variety. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ^ Pamela McClintock (November 16, 2008). "'Quantum' posts Bond's best opening". Variety. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ Staff (November 18, 2008). "Jolie's tears for her late mother". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ Staff (October 7, 2008). "Eastwood jokes about VP offer". rte.ie. Radio Telefís Éireann. Archived from the original on December 11, 2023. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ^ Jim Schembri (December 24, 2008). "Modern morality tales". The Age. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved December 24, 2008.

- ^ Geoffrey Macnab (March 13, 2009). "Julia Roberts – Has cinema's queen lost her crown?". The Independent. Archived from the original on March 16, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ Pamela McClintock (March 13, 2009). "'Watchmen' battle superhero bias". Variety. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ Pamela McClintock (March 10, 2009). "Clint mints overseas box office". Variety. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c Nikki Finke (November 1, 2008). "Halloween Scared Weekend Filmgoers". Deadline Hollywood Daily. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ Joshua Rich (November 2, 2008). "'High School Musical 3' Scares up Another Win". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 6, 2008. Retrieved November 2, 2008.

- ^ a b Pamela McClintock (November 2, 2008). "'School' still rules box office". Variety. Retrieved November 3, 2008.