Battle of Broken Hill

| Battle of Broken Hill | |

|---|---|

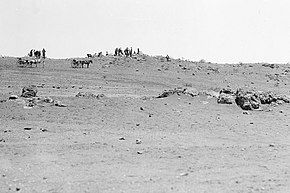

The White Rocks Reserve at Broken Hill, the location of Mahomed and Abdullah's last stand after their attack on the picnic train on New Year's Day 1915. | |

| Location | Broken Hill, Australia |

| Date | 1 January 1915 |

| Target | Civilians |

Attack type | Mass murder, massacre |

| Deaths | 6 (including both perpetrators) |

| Injured | 7 |

| Perpetrator | Gool Badsha Mahomed Mulla Abdullah |

| Motive | Support for the Ottoman Empire in World War I |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam in Australia |

|---|

|

| History |

|

| Mosques |

| Organisations |

| Islamic organisations in Australia |

| Groups |

| Events |

| National Mosque Open Day |

| People |

The Battle of Broken Hill was a fatal incident which took place in Australia near Broken Hill, New South Wales, on 1 January 1915. Two men fired with rifles at a passing picnic train, killing four people and wounding seven more, before being killed by police and military officers. Though politically and religiously motivated, the men were not members of any sanctioned armed force and the attacks were criminal. The two men, Mulla Abdullah and Gool Badsha Mahomed, were later identified as Muslim 'Ghans' from colonial India who believed they were fighting a holy war under orders from the Turkish Sultan.

The events at Broken Hill on New Year's Day 1915 represent the only documented engagement with the enemy to take place on Australian soil during World War I.[1]

The events of New Year's Day 1915

[edit]The Manchester Unity Picnic

[edit]New Year's Day in 1915 was to be the thirteenth annual picnic and sports gathering of the combined lodges of the Manchester Unity Independent Order of Oddfellows in Broken Hill. For the previous twelve years, January 1 had become locally known as the day of the Manchester Unity Picnic, an annual public celebration held at Penrose Park at Silverton, sixteen miles (26 km) north-west of Broken Hill. Each year a special train service was organised by the M.U.I.O.O.F. to convey their guests to the picnic ground.[2] The line to Silverton was part of a railway operated by the Silverton Tramway Company.[3]

At 10 o'clock on Friday morning, 1 January 1915, a train consisting of two brake vans and 40 ore trucks, modified with temporary bench seating, left the Sulphide-street station with 1,200 picnickers on board, seated in the open ore trucks. The train made a brief stop at the Railway Town station before resuming the journey.[1] When the train had travelled for two miles (3 km) on its way to Silverton, on the outskirts of Broken Hill, near the cattle yards and opposite the cemetery, the passengers noticed a white ice-cream cart and horse on the northern side of the line, close to the railway fence. The cart was flying a flag with a white star and crescent, the flag of the Ottoman Empire. Two "dark men" wearing turbans were seen nearby, crouching behind a bank of earth and within a trench excavated for the pipe-line from the Umberumberka reservoir near Silverton.[4][5][6]

The two men hiding in the trench, fifty yards from the railway tracks, were members of the local Muslim community, living at the 'ghantown' encampment at North Broken Hill.[7][8] As the picnic train began to pass their position, the intention of the men was to shoot as many of the passengers in the open ore trucks as they could.[9] The two men were:

- Mulla Abdullah, aged about 60 years, a former camel-driver and halal butcher.[10][11][12]

- Gool Badsha Mahomed, aged about 40 years, a former cameleer and local ice-cream vendor.[13][14]

Background to the attack

[edit]In late October 1914, the Ottoman Empire had joined with Germany in the war against the Allied powers of Britain, France and Russia. In November 1914, Ürgüplü Mustafa Hayri Efendi, the Ottoman Sheikh al-Islam, spiritual advisor to the Turkish Sultan, proclaimed a holy war on behalf of the pan-Islamic world.[15] This "appeal to Moslem fanaticism" was viewed with immediate concern by Britain and her allies, particularly in regard to the large Muslim populations of Egypt and India.[16][17]

Mulla Abdullah and Gool Mahomed lived on the outskirts of the northern camel camp at Broken Hill. Gool Mahomed had purchased ammunition for his rifle in mid-December 1914, and the two men were known to have carried out target practice in the weeks before the attack.[18]

Several days before the attack on the picnic train, Mulla Adbullah was convicted in the Police Court for slaughtering sheep on unlicensed premises, a breach of municipal regulations. He had been reported by the sanitary inspector, Mr. Brosnan, and it was not Adbullah's first offence.[19]

The two men transported their rifles and ammunition to the location of the attack in Gool Mahomed's ice-cream cart, which was a familiar sight in Broken Hill.[1] When they left in the cart on the morning of the attack, they said "they were going into the bush".[18] Two boys named Rex Thorn and Reg Bray were returning from the Sulphide-street station, after having driven "some lady passengers to join the picnic train". At about 9.30 a.m., they encountered the ice-cream cart, carrying two men wearing turbans, near the Pell-street railway crossing. The driver, Mulla Abdullah, signalled for the boys to stop and asked if the picnic train to Silverton had gone, to which the lads replied "No". He then asked, "What time does it start?" He was told 10 a.m., to which Abdullah then asked, "What is the time now?" After the encounter, the driver said "Good-day" and drove on.[20]

The attack on the picnic train

[edit]The men waiting to attack the picnic train were both armed with breech-loading rifles. Abdullah was armed with an older-style Snider-Enfield rifle with cartridges in a home-made bandolier. He also had a revolver and cartridges and a knife in a sheath. Gool Mahomed was armed with a more modern Martini-Henry rifle.[21][22] The men had spread blankets on the ground within the trench, to lie on as they waited for the train to arrive.[23]

As the train passed, the two men started firing their weapons at the passengers. The wagons' low sides left the picnickers' upper bodies and heads completely exposed. The two assailants fired at the passengers as the train passed their position, firing an estimated 20 to 30 shots in all.[4]

When John Coe, the railway guard in the brake van at the rear of the train, heard the reports of firearms he looked along the train and saw "two dark men" in the Umberumberka pipeline trench with rifles in their hands, shooting at the passengers. At first, Coe thought they were firing blank cartridges, but when he saw the 'kick' of the rifles, he realised they were firing ball cartridges.[5] The passengers were also initially unconcerned, thinking that the shots were being discharged in honour of the train's passing or "perhaps a sham fight or some target practice".[24] A witness to the events from nearby Railway Town heard the people in the ore trucks shout "hooray" as the firing began, and then soon afterwards screams were heard.[5]

Alma Cowie, aged 17 years, was seated in the picnic train beside her boyfriend, Clarence O'Brien, a mill-hand at the South mine. As soon as O'Brien realised "the two men with turbans" were firing their weapons at the train he turned to tell Alma "to crouch down", but as he did he saw her "falling as though in a faint". O'Brien put his arm around her for support, "and as he did so the blood streamed down his arm from a wound in the top of her head". Fatally wounded, Alma Cowie died after 45 minutes. Mary Kavanagh, in the same truck, was also wounded.[5]

Another fatality was William Shaw, riding in one of the ore trucks with his family members. Shaw was a municipal employee, a foreman in the Sanitary Department. Soon after the shooting began, Shaw, seated beside his wife Alice, fell forward with a wound in his back, calling out, "I'm shot". The couple's 15-year-old daughter Lucy was struck in the elbow with a bullet and another young girl in the same truck was hit on the leg, the bullet only bruising the skin. The other passengers laid the severely wounded Shaw on one of the bench seats, but he died soon afterwards.[5]

Also killed during the attack was Alfred Millard, who had been riding along the pipe track on a bicycle. Millard was a resident of Balmain, but had come to Broken Hill to supervise the laying of the wooden pipe-line from the Umberumberka dam; he was boarding at Mrs. Beaumont's house in Cobalt-street, Railway Town. Millard had left his residence at 10.20 a.m. to repair a leak in the pipe-line, carrying photographic equipment in a case, when he was fired upon by Mahomed and Abdullah during their assault on the train passengers. A witness reported seeing four shots fired at Millard, one of which struck his back, causing him to fall from his bicycle "in a crouching position". By the time medical attention arrived at the scene, he had died.[25][5] Millard had taken his camera that day with the expressed purpose of taking a photograph of the picnic train "as the people in Sydney had no idea what a Broken Hill picnic train was like and would be greatly interested in a picture of one".[26]

The men in the trench continued firing "until the train had passed a good distance from them". In order to assess the situation Coe, the railway guard, applied the brakes and the train stopped at the Picton siding, about 850 yards beyond the position of the two assailants. However, with the train stopped Mahomed and Abdullah resumed firing. Some of the passengers had gotten off the train, but Coe ordered them back and the train went on a further three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) to the Silverton Tramway Company's reservoir. An assistant guard, William Elsegood, ran the half a mile to the pumping station and used the telephone there to "raise the alarm" in Broken Hill.[5]

At about 10.50 a.m. a relief train, with men with rifles, arrived at the reservoir. Soon afterwards, doctors and others arrived at the scene in motor cars. Doctors Archibald Nairn and Owen Moulden both attended to the wounded passengers.[5]

Police and military response

[edit]When the alarm was raised from the pumping station, Inspector Miller mobilised a force of policemen. Miller then contacted Lieutenant Resch, who began to gather all available military personnel in the township. Miller then sent Sergeants Gibson and Dimond and a force of armed police in two motor cars to follow the movements of Mahomed and Abdullah, from the site of the attack on the train, leading north-east along the western outskirts of the town.[4]

A 70-year-old tinsmith, Thomas Campbell, was expecting a visit from a friend and was standing in the doorway of his house at Allendale, on the western edge of the township (north-east of the scene of the picnic train attack). Suddenly, he saw Abdullah and Mahomed come around the side of his house carrying guns. Campbell called out to them: "What! Are you out rabbiting?" Without a word they raised their rifles and one of them fired, hitting the tinsmith in the stomach. As Campbell stepped back inside and closed the door, he heard one of the assailants say, "Send a bullet through the door" and a second shot was fired. The two men then walked on. After they had left, Campbell made his way to the nearby Allendale Hotel and was taken to hospital.[27] Campbell's house was on a rise called Rocky Hill. A resident of nearby Wyman-street, whose house Mahomed and Abdullah walked past by after shooting Tom Campbell, theorised that "the Turks went to Campbell's little two-roomed house with the object of entrenching themselves there, and finding it occupied, simply shot Campbell out of blood lust".[28] After shooting Campbell the two assailants continued in a north-easterly direction, skirting the township.

About three-quarters of a mile from the West Camel Camp one of the motor cars carrying the pursuing policemen broke down. Gibson and Dimond and six other police then proceeded in the remaining car. As they approached the camp the policemen saw Gool Mahomed and Mulla Abdullah, dressed in turbans and khaki coats, heading off in a northerly direction. About 250 yards past the camp the two men were ascending a hill with a rocky outcrop; as the car drew closer the men turned, knelt down and fired shots at the approaching vehicle. The police then got out of the car and returned fire. Constable Mills was wounded twice during the exchange of fire.[6]

The battle

[edit]

After shooting Tom Campbell the two assailants continued in a north-easterly direction, skirting the township, and eventually took cover amongst rocks several hundred yards west of the Cable Hotel. The jagged white quartz outcrop, known locally as Cable Hill, was in an elevated position above the surrounding country and nearby residences. The hill afforded good cover, but the two men were soon faced with overwhelming armed opposition.[4] Police and soldiers numbering about thirty men, under the direction of Inspector Miller and Lieutenant Resch, caught up with Abdullah and Mahomed in their defensive position behind the rocks on Cable Hill and used what cover they could find to fire at them. A number of armed civilians, members of rifle clubs and citizen militia, also rushed to the location and joined the fight. Some of those who joined the fight "exposed themselves rather rashly in their efforts to get a shot".[4]

James Craig, a 69-year-old labourer, was in his yard during the exchange of gunfire in the vicinity of his house and was hit by a stray bullet and later died in hospital. Craig was living at West Broken Hill with his widowed stepdaughter, May Shirff Khan, in a house about a hundred yards from the Cable Hotel. Craig had been cutting wood when the gunfire began, and bullets were "falling around the house". His stepdaughter told him, "He had better come in, as he might be shot". But soon afterwards, Craig was wounded in the lower back, the bullet going through his hip bone and entered the abdominal cavity. He was brought to the District Hospital early in the afternoon and died after several hours "from shock due to the injury".[5]

During the gun battle between the police and the assailants, the police "were rendered great assistance" by Walhanna Asson, a Punjabi-speaking camel-owner, originally from Peshawar, whose brother was serving in the British army in India. Asson's house was near the scene of the fight; when a police officer was shot, Asson carried water to the wounded constable while he himself was under fire from Abdullah and Gool. When late-comers arrived on the scene to assist the police, "seeing a man of his color so near the vicinity of the firing line", they assumed he was "one of the enemy". It was reported that Asson "would certainly have been slain... had not the police given him their protection and explained the situation".[21]

Khan Bahadur, a camel-owner and driver, was at his residence near the Cable Hotel when Abdullah and Gool walked by his house. One of them fired at Bahadur and said, "Don't follow me or I will shoot you". When the police arrived the 'Turks' had taken shelter behind rocks about five hundred yards away. Some of the police took cover in Bahadur's house and fired from the windows.[21]

The battle lasted almost two hours. Towards the end very little shooting came from the rocky outcrop and most of it was off target. At about one o'clock in the early afternoon, "a rush took place to the Turk's stronghold", and they were both found lying on the ground behind the rocks. Both had many wounds; the older man, Abdullah, was dead and Mahomed was severely wounded. Mahomed had been shot in the chest, the right forearm, the left thigh, his left-hand fingers were lacerated, and a bullet had grazed his neck. He was conveyed to the hospital but died shortly afterwards from shock.[4][6]

It was recorded that both men "wore the dress of their people, with turbans on their head".[4] The attackers left notes connecting their actions to the hostilities between the Ottoman and British Empires, which had been officially declared in October 1914. Believing he would be killed, Gool Mahomed left a letter in his waist-belt which stated that he was a subject of the Ottoman Sultan and that, "I must kill you and give my life for my faith, Allāhu Akbar." Mulla Abdullah said in his last letter that he was dying for his faith and in obedience to the order of the Sultan, "but owing to my grudge against Chief Sanitary Inspector Brosnan, it was my intention to kill him first".[29] Turkish sources claim that the letter from the Ottoman Sultan was a forgery, and that the Turkish flag found with the perpetrators was planted. It is claimed that the incident was attributed to Turks in order to rally the Australian public for the war.[30]

The German Club

[edit]

That night, a "turbulent crowd", numbering several hundred, assembled in Argent Street. At about eight o'clock, the crowd, "mostly of young men and youths", were in the vicinity of the Police Station. Many in the crowd were of the opinion that "the Germans were the authors of the outrage", which led to the cry of "To the German Club, lads". The crowd then moved to the German Club premises in Delamore Street, where "the scene became riotous in the extreme". Stones were thrown against the walls and through the windows, while the crowd cheered and "sang snatches of patriotic songs", interspersed with "terrible execrations" directed at "all foreigners, German, Turks, and Afghans in particular".[31][29]

After a few minutes, some of the men forced an entrance to the German Club and caused damage inside. Eventually, those inside were called out and others advanced and emptied two bottles of methylated spirits onto the front portion of the clubhouse. The fuel was lit, and flames quickly began to spread. Within a short time "the whole front of the building was one mass of fire, which was rapidly burning the contents and exterior woodwork, including the verandah".[31]

With the German Club ablaze, the constable attempted to switch on the bell in the nearby street fire box, but "the crowd for a long time hampered his progress to the instrument, although they did not actually lay violent hands upon him to stop it". Eventually the constable was able to reach the bell to alert the fire brigade.[32][33]

The North Camel Camp

[edit]The North Camel Camp was a settlement of local Muslims at the extreme northern end of Williams Street in North Broken Hill. It consisted of "a few galvanised-iron buildings straggling irregularly around an area of two or three acres", the homes of camel drivers and other camp residents. The area included the business depot for the camel-based transportation of merchandise to surrounding stations and settlements. The most substantial building at the camp was a mosque, a single room twenty by fifteen feet in dimensions with an alcove in the wall and heavily carpeted, but otherwise having no furniture.[34]

After the angry crowd had attacked and set fire to the German Club, the authorities decided to send a contingent of police and military to protect the mosque at the North Camel Camp. An advance guard arrived in several cars at about nine-thirty that night and were greeted at the mosque by two "priests of Islam" dressed in turbans and robes. The policemen briefly entered the mosque and then explained to the two men that they were there to "preserve order", as they "feared a repetition of the proceedings that had taken place a little earlier in the evening at the German Club". Soon afterwards, "a crowd apparently numbering some hundreds was seen surging down the road". A detachment of military arrived at about the same time and managed to hold the agitated crowd at bay. After about half an hour, "the inaction of waiting in idleness had its effect", and the crowd began to drift away until "the military and police were left in sole possession of the ground".[34]

When the soldiers and police entered the mosque on the night of January 1, they had done so without removing their boots. Though the circumstances were exceptional and "at the time none of those entering gave the matter a moment's thought", the desecration of the mosque in this manner caused considerable disquiet amongst the local Muslim community. Several days later, Captain Hardie and Police Inspector Miller "paid a conciliatory visit to the mosque" and met with the "chief priest" about the matter.[35]

The following days

[edit]In the days following the murderous attack on the picnic train, the bodies of Mulla Abdullah and Gool Badsha Mahomed were buried by the police at an undisclosed location. There may have been an earlier attempt to dig graves for the two murderers in the local Muslim cemetery. On the night of January 2, a gravedigger was discovered at work in the corner of the cemetery, digging two graves without regard to the alignment according to Islamic custom. The work was stopped and local Muslims "raised their voice in protest at their burial place being utilised for the interment of cowardly slaughterers of defenceless women and children". The cemetery caretaker was directed to allow no burials in the Muslim section "without special order".[36]

On Sunday, January 3, thousands of people assembled in Broken Hill to witness the funerals of the four victims.[37]

The Silverton Tramway Company refunded in full the fares for the picnic train, and the money was used to launch a public relief fund.

A coronial inquest was held on January 7 in the Broken Hill Courthouse on the bodies of the victims of "the New Year's Day tragedy".[5] The next day the Coroner held an inquiry into the deaths of Gool Mahomed and Mulla Abdullah.[6]

The assailants

[edit]- Mulla Abdullah – born in about 1854, probably in Afghanistan or an adjoining region of modern Pakistan. Abdullah was literate in Dari, a Persian dialect and the most widely-spoken language of Afghanistan. Abdullah had arrived in Broken Hill around 1898 and worked as a camel driver.[13][38] By 1909, Abdullah was probably working as a halal butcher at the North Camel Camp, and by 1912, he had been granted a license by the Broken Hill Municipal Council.[10] Abdullah was described as having "a very reserved disposition, rarely speaking to anyone". He was considered to be "always childish and simple in his ways". Local children were in the habit of throwing stones at Abdullah, "but beyond occasionally complaining to the police he was never known to retaliate".[39] It was generally agreed by local Muslims and the police that Gool Mahomed had influenced and persuaded Abdullah to join him in his attack on the picnic train.[40][39][41][A]

- Gool Badsha Mahomed – born in about 1874 in the mountainous Tirah region of Afghanistan, south-east of Kabul on the modern Afghan-Pakistani border. He was from the Afridi tribe with a proud martial tradition, speaking a dialect of the Pashto language. Gool Mahomed came to Australia as a young man and worked as a camel-driver. He left Australia to join the Turkish Army, fighting in four campaigns under Sultan Muhammed Rashid V, during a period when the extent of the Ottoman Empire was considerably reduced when territories were lost in Europe and North Africa. Mahomed returned to Australia in about 1912, but by then the camel carrying-business was in decline.[13][42][41] Mahomed worked in the British Mine, but was retrenched after late July 1914, when the war commenced, after which he rented a room in Argent-lane. He went on a trip with a camel-team trading from Tarrawingee. In early December, he returned and was often seen in the company of Mulla Abdullah in the vicinity of the North camp.[6] He became an ice-cream vendor, selling from his horse-drawn cart.[13]

The men who attacked the picnic train were misleadingly labelled "Turks" in newspaper reports, a categorisation bolstered by the Ottoman flag they attached to their cart and the letters they left explaining their actions.[43][44][45]

The victims

[edit]- Alma Priscilla Cowie – born on 3 March 1897 at Broken Hill, the seventh of fourteen children of William Cowie and Emily (née Henwood).[46] The family lived at Railway Town (south-west of the township centre) and Alma's father was a dairyman.[19][47]

- Alfred Elvin Millard – born in about 1884 at Balmain, the eldest child of Alfred Millard and Mary (née Hill). Millard married Mary Jane Hamilton in 1900 at Balmain North and the couple had a son, born in 1902 at Taree.[46] Millard was employed by the Wood Pipe Company from about 1902.[26] He was a resident of Reynolds-street, Balmain. He came to Broken Hill to supervise the laying of the wooden pipeline of the Umberumberka water service, and from August 1914 was boarding with the Beaumont family in Cobalt-street, Railway Town.[48][49][26]

- William John Shaw – born in 1868 at Nairne in South Australia, the eldest child of John Shaw and Mary Ann (née Weatherall). Shaw married Alice Ide in January 1898 at Crystal Brook, South Australia, and the couple had five children born at Broken Hill between 1899 and 1907. Sanitation inspector, a foreman in the Sanitary Department, municipal employee.[46]

- James Craig – born in about 1845 in England; aged 69.[46] Labourer.[19]

The names of the wounded were:

- Rose Crabb, aged 30 years, of Marks-street, Waterworks Hill; shot through the shoulder bone (or groin and side), condition not critical.

- Alma Crocker, aged 34 years, arrived recently from Peterborough and staying with Mrs. Bray of Beryl-lane; shot in the jaw.

- Mary Kavanagh, aged 23 years, tailoress, of Cummins-street; shot through the base of the skull, condition serious (daughter of Walter and Anastasia Kavanagh). Mary married Ted Kelly on 5 June 1916 at Broken Hill.[50] The couple had seven children. Mary Kavanagh died in April 1946 at Broken Hill.[46]

- Lucy May Shaw, aged 15 years, of Wolfram-street (daughter of William and Alice Shaw); bullet in the elbow. The bullet was extracted, and she was allowed to return home.

- George F. Stokes, aged about 15 years, of the corner of Cummins and Garnet-streets; shot in the shoulder and chest, condition serious.

- Thomas Campbell, aged 70 years, tinsmith, of Rocky Hill, Allendale, West Broken Hill; shot in the abdomen at his home near the Allendale Hotel. Campbell was released from hospital in late February 1915.[27]

- Constable Robert Mills, wounded twice, shot in the groin and thigh; condition not critical.[19][51][46]

Aftermath

[edit]Immediate events

[edit]On Monday, 4 January, the local military and several policemen arrested eleven "alien enemies resident in Broken Hill". The arrests were carried out without incident. The numbers and nationalities of those detained were six Austrians, four Germans and one Turk.[52]

The next day, the mines of Broken Hill fired all employees deemed enemy aliens under the 1914 Commonwealth War Precautions Act. Six Austrians, four Germans and one Turk were ordered out of town by the public. Shortly afterwards, all enemy aliens in Australia were interned for the duration of the war.[33]

German propaganda

[edit]The Sydney journal The Bulletin published a burlesque of the incident in the style of German propaganda, suggesting the Germans lauded the attack as a victorious military battle between Turkish forces and recruits on a troop train. Supposedly the Turkish attackers killed 40 and wounded 70 (ten times the real figures) for the loss of only two dead. The parody was, for some reason, taken seriously by other newspapers, which published it almost verbatim as a genuine example of German propaganda. The story was picked up by international papers in the United States, the United Kingdom and New Zealand. When clippings from the foreign papers filtered back to Australia in the letters home of serving soldiers, it only reinforced the belief that the story in the Bulletin was true. The 'fake news' was revived as an example of German mendacity by Australian papers during the Second World War and even as late as 1951 in Broken Hill's own Barrier Daily Truth newspaper.[53]

More recently

[edit]In the late 1970s, attempts were made to turn the story into a film The Battle of Broken Hill, to be directed by Donald Crombie, but this did not eventuate.[54][55]

Nicholas Shakespeare wrote the novella Oddfellows (2015) based on the events at Broken Hill on 1 January 1915.[56]

The battle is the subject of the song 'Battle of Broken Hill' by the Sydney-based Celtic-punk band Handsome Young Strangers, found on their 2016 EP of the same name.[citation needed]

In 2014, the Greek Australian genocides scholar Panayiotis Diamadis noted that the attack occurred only a few weeks after the declaration of jihad (holy war) on 14 November 1914 by Sultan Mehmed V and Shaykh al-Islām (primary religious leader) Essad Effendi of the Ottoman Empire against Great Britain and the Allies.[57][58]

The Australian government refused requests to fund a commemoration of the event for its 100th anniversary.[59] A ceremony marking the centenary of the massacre was held at Broken Hill railway station on 1 January 2015.[60]

A 2019 Turkish film by Can Ulkay, Türk Isi Dondurma (Turkish Ice Cream) presents the "recruits on a troop train" version of the story.[61]

Heritage listing

[edit]On 29 June 2018, the two significant sites connected to the 1915 New Year's Day picnic train attack at Broken Hill were added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register. They are:

- Picnic Train Attack Site, located beside the Picton Sale Yards Road (at the end of Morgan Street), on the western edge of Broken Hill.

- White Rocks Reserve (previously known as Cable Hill) is located near Schlapp Street on the north-western edge of the city.

The properties are owned by the New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment and the community group, Silverlea Services.[1]

Notes

[edit]- A.^ Christine Stevens, in her article on Mulla Abdullah in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, describes her subject as an "Islamic priest" who "may have come from a family of mullahs". She claims Abdullah served as a mullah to the Afghans living in the Broken Hill 'ghantown'; "he led the daily prayers, presided at burials and killed animals al halal for food consumption".[62] While Abdullah was undoubtedly a butcher who slaughtered animals by the prescribed method according to Islamic law (by which his meat was considered to be halal), there is no evidence to support the contention he was a religious leader to the Muslim community at Broken Hill.[10] The mosque at the North Camel Camp already had a mullah in place (unnamed in press reports, but referred to as "the chief priest"). On the night of 1 January 1915, after the shootings, soldiers and police had entered the mosque without removing their boots (considered to have been a desecration of the building). On January 5 Captain Hardie and Inspector Miller, in a conciliatory gesture regarding the incident, met with "the chief priest" at the mosque.[35] In a 1922 report the mullah of the North Camp mosque was named as Mullah Sher Ali, who had been in charge of the mosque "at North Broken Hill for several years".[63] In 1927 Mullah Sher Ali was one of only two mullahs in Australia (the other being in Perth).[64] Christine Stevens concludes that, by 1915, Abdullah "was a grey-bearded zealot, fiery when insulted".[62] This statement is also unsupported by the evidence. Of the two men, the younger man Gool Badsha Mahomed could more accurately be described as a zealot. It was he who had fought in four campaigns under the Turkish Sultan and, at the outbreak of hostilities between the Ottoman Empire and the British Empire, he wrote to the Turkish Minister of War to apply to enlist in the Turkish army. Gool Mahomed, described as a "warlike and very religious man", carried "the Sultan's order" in his waistbelt as he shot at the civilians in the picnic train and fought against the police and military, having left a message explaining his actions that read, "I must kill your men and give my life for my faith by order of the Sultan".[41] In contrast to Gool Mahomed, Abdullah was described as having "a very reserved disposition, rarely speaking to anyone". He was considered to be "always childish and simple in his ways". Local children were in the habit of throwing stones at Abdullah, "but beyond occasionally complaining to the police he was never known to retaliate".[39] It was reported that Abdullah had ceased wearing his turban years before the picnic train attack, "since the day some larrikin threw stones at me, and I did not like it".[43] It was generally agreed by local Muslims and the police that Gool Mahomed had influenced and persuaded Abdullah to join him in his attack on the picnic train.[40]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "1915 Picnic Train Attack and White Rocks Reserve". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H02002. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ M.U. Picnic: Under the Pepper Tree at Silverton, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 2 January 1914, page 4.

- ^ Lew Roberts (1995). Rails to wealth: a history of the Silverton Tramway Company Limited, Broken Hill's railway service. Melbourne: L.E. Roberts. ISBN 978-0-646-26587-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g War in Broken Hill: Attack on a Picnic Train, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 1 January 1915, page 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j New Year's Day Tragedy: Inquest Resumed at the Courthouse, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 7 January 1915, page 2.

- ^ a b c d e New Year's Day Tragedy: Inquest on the Turks, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 8 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ Peter Scriver (2004), 'Mosques, Ghantowns and Cameleers in the Settlement History of Colonial Australia', Fabrications (Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand), Vol. 13, No. 2, pages 19-41.

- ^ The New Year's Day Tragedy: The Battlefield, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 6 January 1915, page 2.

- ^ Goltz & Adams, page 66-67.

- ^ a b c The Slaughtering of Meat, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 25 August 1909, page 5; Abdullah was a licensed butcher by 1912 (see Municipal Council, Barrier Miner, 26 January 1912, page 5).

- ^ Butcher Fined, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 18 December 1915, page 3.

- ^ New South Wales Death Registration: Mulla Abdullah, aged "60 years", Broken Hill; Reg. No.: 3120/1915.

- ^ a b c d Stevens, Christine (2005). "Mahomed, Gool Badsha (1875–1915)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943.

- ^ New South Wales Death Registration: Gool Badsha Mahommed, aged "40 years", Broken Hill; Reg. No.: 3119/1915.

- ^ Miscellaneous, Western Mail (Perth), 27 November 1914, page 16.

- ^ Egypt and the War, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 November 1914, page 8.

- ^ Mustafa Aksakal (2011), 'Holy War Made in Germany'? Ottoman Origins of the 1914 Jihad, War in History, Vol. 18, No. 2 (April 2011), pages 184–199.

- ^ a b The Two Turks, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 4 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ a b c d Turks Attack Train, The Argus (Melbourne), 2 January 1915, page 9.

- ^ Boy's Story: Questioned by Murderers at Goods Station, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 2 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ a b c Turks Identified, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 1 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ The Turk's Rifles, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 4 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ Early on the Scene, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 4 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ "For Revenge": Broken Hill Tragedy, Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 4 January 1915, page 6.

- ^ The Umberumberka Scheme, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 21 January 1914, page 6.

- ^ a b c Mr. Millard's Last Good-bye, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 4 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ a b New Year's Day Tragedy: The Story of Mr. Thomas Campbell, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 24 February 1915, page 4.

- ^ Mr. V. Hanson's Story, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 4 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ a b Christine Stevens (1989), Tin Mosques and Ghantowns: A History of Afghan Cameldrivers in Australia, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, page 163; ISBN 0-19-554976-7

- ^ Özdil, Yilmaz (3 January 2013). "Sayın Apo Anzak oldu!". Hürriyet (in Turkish). Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ a b Last Night's Sequel: German Club Fired, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 2 January 1915, page 5.

- ^ German Club Fire, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 2 January 1915, page 5.

- ^ a b Mary Lucille Jones (date), 'The Years of Decline: Australian Muslims 1900–1940', in Mary Lucille Jones (ed) An Australian pilgrimage: Muslims in Australia from the Seventeenth Century to the Present, Victoria Press (in association with the Museum of Victoria), page 64; ISBN 0-7241-8450-3

- ^ a b At the North Camel Camp, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 2 January 1915, page 5.

- ^ a b The Mohamedan Mosque, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 6 January 1915, page 2.

- ^ Assassins' Bodies: Grave-digging Stopped, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 4 January 1915, page 2.

- ^ The New Year's Day Tragedy: Funerals of the Victims, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 4 January 1915, page 2.

- ^ New South Wales death registration (Reg. No. 3120/1915); Mulla Abdullah's age was recorded as 60 years.

- ^ a b c The Turk Attackers: Who and What They Were, by "One Who Knew Them", Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 2 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ a b The Reason: Inspector Miller's View, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 2 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ a b c The Barrier Fight, The Express and Telegraph (Adelaide), 13 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ New South Wales death registration (Reg. No. 3119/1915); Gool Badsha Mahommed's age was recorded as 40 years.

- ^ a b At the Sultan's Command, The Argus (Melbourne), 6 January 1915, page 9.

- ^ The New Year's Day Tragedy: The "Confessions", Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 31 January 1915, page 3.

- ^ No Title (documents and translations), Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 31 January 1915, page 3.

- ^ a b c d e f Family records, per Ancestry.com.

- ^ Fall From a Buggy, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 20 November 1913, page 4.

- ^ One of the Victims, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 2 January 1915, page 5.

- ^ Alfred Elvin Millard, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 10 January 1915, page 3.

- ^ Marriages: Kelly - Kavanagh, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 15 July 1916, page 4.

- ^ List of Killed and Wounded, Barrier miner (Broken Hill), 1 January 1915, page 2.

- ^ A Fresh Development; Alien Enemies Arrested, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 4 January 1915, page 4.

- ^ Whyte, Brendan. "Propaganda eats itself: The Bulletin and the battle of Broken Hill". Sabretache, Vol. 57, No. 3, September 2016: 48–57.

- ^ David Stratton, The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson 1980, page 281

- ^ "Production Survey", Cinema Papers, January 1978, page 251

- ^ Shakespeare, Nicholas (2015). Oddfellows. Vintage Australia/Random House. ISBN 9780857987181.

- ^ Panayiotis Diamadis, "History repeating: from the Battle of Broken Hill to the sands of Syria", The Conversation, 3 October 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ Daniel Allen Butler (2011). Shadow of the Sultan's Realm. Potomac Books. p. 135. ISBN 9781597974967.

- ^ "Battle of Broken Hill an act of war or terrorism won't be commemorated" by Damien Murphy, The Sydney Morning Herald, 31 October 2014

- ^ Breen, Jacqueline. "Broken Hill remembers victims of 1915 attack by gunmen brandishing Turkish flag". ABC News. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ Türk Isi Dondurma at IMDb

- ^ a b Stevens, Christine (2005). "Abdullah, Mullah (c. 1855–1915)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943.

- ^ Death of Khan Bahader, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 24 July 1922, page 3.

- ^ The Office of Mullah, The Advertiser (Adelaide), 18 August 1927, page 14.

- Sources

- Bilal Cleland (2000), 'The Muslims in Australia: A Brief History', published by Islamic Human Rights Commission, Wembley, U.K.

- Helen Goltz and Chris Adams (2019); Joanne James (editor), Grave Tales: True Crime: Stories Not Laid to Rest (Volume 1), Greenslopes, Qld.: Atlas Productions, ISBN 9780987160577.

Further reading

[edit]- Roberta J. Drewery (2008), Treks, Camps & Camels: Afghan Cameleers, Their Contribution to Australia, Rockhampton, Qld.: R.J. Bolton.

- Christine Ellis (2015), Silver Lies, Golden Truths: Broken Hill, a Gentle German and Two World Wars, Mile End, South Australia: Wakefield Press, ISBN 9781743053508.

- Richard H. B. Kearns (1975), Broken Hill: Volume 3. 1915-1939: New Horizons, Broken Hill, NSW: Broken Hill Historical Society, ISBN 0959949569.

- David Matheson (2015), 'The Battle of Broken Hill', Australian Railway History, Vol. 66 Issue 927 (January 2015), page 4.

- Nicholas Shakespeare (2015), Oddfellows, North Sydney: Vintage/Random House Australia, ISBN 9780857987181.

- Robert J. Solomon (c.1988), The Richest Lode: Broken Hill 1883-1988, Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, ISBN 0868063339.

- Christine Stevens (2002), Tin Mosques & Ghantowns: A History of Afghan Cameldrivers in Australia, Alice Springs, N.T.: Paul Fitzsimons, ISBN 0958176000.

External links

[edit]- Sharing the Lode: The Broken Hill Migrant Story

- The Battle of Broken Hill film

- Battle of Broken Hill, Postcards TV show visits the area

- "Broken Hill Picnic Train Massacre" Archived 14 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine by Brendan Whyte in Strategy & Tactics, no. 231, pp. 30–31, November/December 2005 (11 MB)

- Battles of World War I involving Australia

- Mass murder in 1915

- History of Broken Hill

- Uprisings during World War I

- Conflicts in 1915

- Murder in New South Wales

- 20th-century mass murder in Australia

- Deaths by firearm in New South Wales

- Spree shootings in Australia

- Islamic terrorism in Australia

- January 1915 events

- 1915 murders in Australia

- 1910s mass shootings in Australia

- Terrorist incidents in the 1910s

- Ottoman Empire in World War I

- Australia–Turkey relations

- Attacks during New Year celebrations

- Terrorist incidents on railway systems

- Railway accidents and incidents in New South Wales

- Railway accidents in 1915

- World War I crimes

- Hindu–German Conspiracy

- 1910s in Islam

- Australia–India relations