Tell al-'Ubaid

العبيد | |

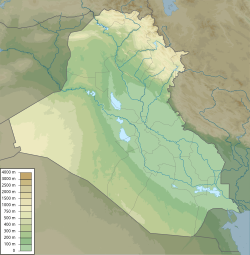

| Location | Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Lower Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 30°58′12″N 46°1′32″E / 30.97000°N 46.02556°E |

| Type | tell, type site |

| History | |

| Periods | Early Dynastic period, Ubaid period, Jemdet Nasr period, Ur III period |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1919, 1923-1924, 1937 |

| Archaeologists | Henry Hall, Leonard Woolley, Pinhas Pierre Delougaz, Seton Lloyd |

Tell al-'Ubaid (Arabic: العبيد) also (Tall al-'Ubaid) is a low, relatively small ancient Near Eastern archaeological site about six kilometers west of the site of ancient Ur and about 6 kilometers north of ancient Eridu in southern Iraq's Dhi Qar Governorate. Today, Tell al-'Ubaid lies 250 kilometers from the Persian Gulf, but the shoreline lay much closer to the site during the Ubaid and Early Dynastic periods. Most of the remains are from the Chalcolithic Ubaid period, for which Tell al-'Ubaid is the type site, with an Early Dynastic temple and cemetery at the highest point. It was a cult center for the goddess Ninhursag.[1] An inscription found on a foundation tablet (BM 116982) in 1919 and on a copper strip in 1923 read "For Nin-hursag: A'annepada, king of Ur, son of Mesannepada, king of Ur, built the temple for Ninhursag". Mesannepada (c. 26th century BC) and A'annepada were rulers of the First Dynasty of Ur.[2]

Its ancient name is unknown but Nutur (alt Enutur) has been proposed, mainly based on the 20th year name of Ur III Empire ruler Shulgi (c. 2094–2046 BC) "Year: Ninḫursaga of Nutur was brought into her temple".[3]

Archaeology

[edit]

Tell al 'Ubaid is an oblong mound measuring approximately 500 meters from north to south and about 300 meters from east to west and rising about two meters above the plain.[4] A fan of surface debris, mainly pottery shards from the Ubaid period but including many lithics (arrow points, knives, microliths etc), extend to the south and southwest of the mound.[5]

The site was first worked by Henry Hall on behalf of the British Museum in 1919. Hall focused on the area which turned out to be the temple of Ninḫursaĝ, a 50 meter long and 7 meter high outcrop on the northern edge of the mound. At the southeast end of the outcrop the only remains of an Ur III period temple built atop the Early Dynastic temple were found with bricks inscribed with the standard inscription of Shulgi (c. 2094–2046 BC), first ruler of the Ur III Empire, "Sulgi, mighty man, king of Ur, king of the lands of Sumer and Akkad".[6] Hall began work clearing the walls of the Early Dynastic temple finding, by the entrance ramp, multicolored mosaic columns, copper statues of lions, bulls, and birds heads, with some parts of the statues are filled with bitumen. A gold bitumen filled bulls horn was also found. Lastly a large (7 feet 9 1/2 inches long by 3 and a half feet wide) copper relief in a copper frame (6" broad and 4" deep) was found depicting a scene of Anzû.[5] Hall found a 37 centimeter high Early Dynastic III dark green stone statue of Kurlil inscribed (according to the excavator) "Kurlil, Keeper of the Granary of Erech, Damgalnun he fashioned, (her) temple he built". Kurlil is known from a similar inscription found on a statue at Uruk.[7]

Later, C. L. Woolley excavated there in 1923 and 1924 on behalf of the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania focusing on completing the excavation of the temple. The excavators defined three occupation periods for the temple:[8]

- First Dynasty of Ur (c. 2500 BC) - plano-convex brick construction[9]

- A period of abandonment

- Uncertain but thought to be Second Dynasty of Ur (c. 2300 BC)

- Ur III period (c. 2100 BC)

A number of statues, mosaics, metal objects, etc were found on the west side of the entrance ramp,as was found by the first excavation of the other side. A marble foundation tablet was found as well as a few fragmentary inscriptions. A cemetery was discovered on a low hillock (350 meters by 250 metesr) 60 meters to the south southeast with 94 graves, mostly from the Early Dynastic Period, primarily Early Dynastic I. The cemetery was in use for a long period and some graves were intercut with others and disturbed. Grave goods included two copper shaft-hole axes and a number of wide conical cups. The remains of a small Ubaid period settlement lay on one part of the hillock.[10][8] Finds included a copper framed frieze of limestone birds set in a black shale background.[11] A final examination, by Seton Lloyd and Pinhas Delougaz on behalf of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, occurred during 4 days in January 1937. The team had finished work at the temple oval at Khafajah and wanted to compare the temple building at Tell al'Ubaid before publishing their final reports. While excavation was conducted a complete site survey was conducted. It was determined that the early temple had been built with reddish brick which at a later date had been filled and covered with grey clay to level the site. The grey clay had eroded in most place and only remained between the walls of reddish bricks. A complete tracing of the temple oval showed it to be 80 meters by 60 meters. Signs of a limestone wall, of the Uruk period based on associated clay cones, which ran under Early Dynastic period temple were noted. Finds included a white marble Jemdat Nasr period cylinder seal (the first excavator had found Jemdat Nasr period pottery shards at the site).[12][13][14]

In the ensuing years more dating and burial practice data has emerged which somewhat changes the interpretation of the graveyard. The graves are oriented NW-SE and NE-SW and it is now known that this is the standard orientation of homes in this period and the burials are now thought to be intramural (buried in the floor of homes).[15] The graves noted by the excavators have now been relabeled as 5 not being graves, 10 undateable due to having no pottery, 16 Early Dynastic I, 59 Early Dynastic II to Early Dynastic IIIa and 6 graves to Early Dynastics lllb to Ur III period.[16] A. M. T. Moore visited the site in 1990 finding previously unnoticed Ubaid period kiln sites with numerous wasters on the west side of the top of the mound about 100 meters south of the temple complex.[4] In 2008 the site was surveyed as part on an investigation of war-time damage to archaeological sites in Iraq by an Iraqi-British team. The team reported extensive damage as a result of "military installations when it was established as an Iraqi command post". This damage included a 4 meter square and 1.5 meter deep pit on the summit of the mound, 10 vehicle bays built around the mound base, and numerous hollows and pits on and around the mound. There was no sign of looting.[17]

History

[edit]

Tell al-'Ubaid was heavily occupied in the Ubaid period (c. 5500–3700 BC) with pottery production, shown by kilns and significant surface finds of shards and wasters. There was occupation during the Uruk period (late 4th millennium BC) based on a foundation wall and clay cones (used to decorate building walls in the period). Some find, including a cylinder seal show that there was a presence in the Jemdet Nasr period but little is known about it. In the Early Dynastic period a temple to the goddess Ninhursag was built possibly over an early Uruk period temple, by the A'annepada (c. 26th century BC) a ruler of the First Dynasty of Ur. The temple lay on a prepared oval similar to the one at Khafajah. This temple was rebuilt later in the Early Dynastic period and then surmounted by a shrine built by Shulgi (c. 2094–2046 BC) of the Ur III Empire.[5][8][12]

Gallery

[edit]-

Recumbent cow, part of a frieze from the facade of the Temple of Ninhursag at Tell al-'Ubaid, Iraq, Iraq Museum

-

Sumerian scene, milking cows and making dairy products. From the facade of the Temple of Ninhursag at Tell al-'Ubaid, Iraq, Iraq Museum

-

A'annepada foundation tablet (BM 116982). British Museum

-

This lion-headed eagle (Imdugud or Anzu) is the Sumerian symbol of the God Ningirsu. In this panel, Anzu appears to grasp two deers, simultaneously. From the temple of Goddess Ninhursag at Tell- Al-Ubaid. British Museum,

-

Wall decoration, stone flower from Tell al Ubaid

-

Inscribed Sherd of Soapstone from Ubaid, Iraq, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Frayne, Douglas R. and Stuckey, Johanna H., "N", A Handbook of Gods and Goddesses of the Ancient Near East: Three Thousand Deities of Anatolia, Syria, Israel, Sumer, Babylonia, Assyria, and Elam, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 219-287, 2021

- ^ Gadd, C. J., "A New Copy of A-Anni-Padda's Inscription from Al-'Ubaid", The British Museum Quarterly, pp. 107-108, 1930

- ^ [1]Firth, Richard, "Notes on Year Names of the Early Ur III Period: Šulgi 20-30", Cuneiform Digital Library Journal CDLJ 2013-1, 2013

- ^ a b Moore, A. M. T., "Pottery Kiln Sites at al ’Ubaid and Eridu", Iraq, vol. 64, 2002, pp. 69–77, 2002

- ^ a b c [2]H. R. Hall, "Season's Work at Ur; Al-'Ubaid, Abu Shahrain (Eridu), and Elsewhere; Being an Unofficial Account of the British Museum Archaeological Mission to Babylonia, 1919", Methuen, 1930

- ^ Frayne, Douglas, "Šulgi", Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 91-234, 1997

- ^ Reade, Julian, "Early monuments in Gulf stone at the British Museum, with observations on some Gudea statues and the location of Agade", vol. 92, no. 2, pp. 258-295, 2002

- ^ a b c [3]Hall, Henry R. and Woolley, C. Leonard, "Al-'Ubaid. Ur Excavations 1, A report on the work carried out at al-'Ubaid for the British Museum in 1919 and for the joint expedition in 1923-4", Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1927

- ^ P. Delougaz, "Planoconvex Bricks and the Methods of their Employment", Chicago, 1933

- ^ Moorey, P. R. S., "The Archaeological Evidence for Metallurgy and Related Technologies in Mesopotamia, c. 5500-2100 B.C.", Iraq, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 13–38, 1982

- ^ [4]Paszke, Marcin Z., "Bird species diversity in 3rd millennium BC Mesopotamia: The case of the Al-Ubaid bird frieze from the Temple of Nin", Bioarchaeology of the Near East 15, pp. 25-54, 2021

- ^ a b P. Delougaz, "A Short Investigation of the Temple at Al-’Ubaid", Iraq, vol. 5, pp. 1–11, 1938

- ^ Seton Lloyd, "Ur-al 'Ubaid, 'Uqair and Eridu. An Interpretation of Some Evidence from the Flood-Pit", Iraq, vol. 22, Ur in Retrospect. In Memory of Sir C. Leonard Woolley, pp. 23-31, (Spring - Autumn, 1960)

- ^ [5] OIP 53. The Temple Oval at Khafajah, Pinhas Delougaz, with a chapter by Thorkild Jacobsen. 1940 (also as ISBN 0-226-14234-5)

- ^ Wright, Henry T., "The administration of rural production in an early Mesopotamian town", Anthropological Papers, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan 38, Ann Arbor, 1969

- ^ Harriet P. Martin, "The Early Dynastic Cemetery at al-'Ubaid, a Re-Evaluation", Iraq, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 145-185, 1982

- ^ Curtis, John, et al., "An Assessment of Archaeological Sites in June 2008: An Iraqi-British Project", Iraq, vol. 70, pp. 215–37, 2008

Further reading

[edit]- Collins P., "Al Ubaid", in Art of the first cities. The third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, J. Aruz, R. Wallenfels (eds.), New Haven, London: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Yale University Press, pp. 84–88, 2003

- Hall, H. R., "The Discoveries at Tell El-’Obeid in Southern Babylonia, and Some Egyptian Comparisons", The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 8, no. 3/4, pp. 241–57, 1922

- Hall, H. R., "Notes on the Excavations of 1919 at Muqayyar, el-‘Obeid, and Abu Shahrein", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 56.S1, pp. 103-115, 1924

- Hall, H. R., "The Excavations of 1919 at Ur, El-’Obeid, and Eridu, and the History of Early Babylonia (Brussels Conference, 1923)", Man, vol. 25, pp. 1–7, 1925

- Korbel, Günther, "Zur zeitlichen Gliederung des Al-Ubaid-Friedhofs in Ur", BaM, vol. 14, pp. 7-14, 1983

- [6]Mansor, Mohammed Abdulridha, and Jabbar Madhy Rashid, "Evaluation of natural radioactivity for building materials samples used in Tall Al Ubaid Archaeologist in Dhi-Qar governorate-Iraq", Samarra Journal of Pure and Applied Science 2.1, pp. 53-66, 2020

- Woolley, C. Leonard, "Excavations at Tell el Obeid", The Antiquaries Journal 4.4, pp. 329-346, 1924

- Woolley, C. L., "Ur and Tel El‐Obeid", Journal of the Central Asian Society 11.4, pp. 313-326, 1924