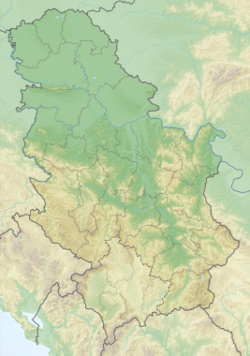

Tara (mountain)

| Tara | |

|---|---|

| Тара | |

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,544 m (5,066 ft) |

| Coordinates | 43°50′54″N 19°27′34″E / 43.84833°N 19.45944°E |

| Geography | |

| Location | Western Serbia |

| Parent range | Dinaric Alps |

Tara National Park | |

| |

| Area | 249.92 km2 (96.49 sq mi) |

| Established | 1981 |

Tara (Serbian Cyrillic: Тара, pronounced [târa]) is a mountain in western Serbia. It is part of the Dinaric Alps and stands at 1,000 to 1,590 m (3,280 to 5,220 ft) above sea level. The mountain's slopes are clad in dense forests with numerous high-elevation clearings and meadows, steep cliffs, deep ravines carved by the nearby Drina River, and many karst caves. The mountain is a popular tourist centre. Tara National Park encompasses a large part of the mountain. The highest peak is Zborište, at 1,544 m (5,066 ft).

National park

[edit]Initial attempts at protecting parts of the mountain occurred in the 19th century. Soon after Serbia's Institute for the Nature Protection was founded in 1948, six reserves were declared on the mountain in 1950. They were followed by the additional three in the 1960s and the 1970s. Tara National Park [1] was established in July 1981.[2] It encompasses Tara and part of the Zvijezda mountain, in a large bend of the Drina River. The area of the park originally was 191.75 km2 (74.04 sq mi)[3][4][5] with altitudes varying from 250 to 1,591 m (820 to 5,220 ft) above sea level. On 5 October 2015, the National Assembly of Serbia adopted the new law of national parks which enlarged the Tara National Park to 249.92 km2 (96.49 sq mi),[6][7] by adding to it the protected area of "Zaovine Landscape of Outstanding Features".[8][9] The park's management office is located in nearby Bajina Bašta. The protective zone of the park, which encircles it, is much larger and spreads over the area of 376 km2 (145 sq mi).[5]

Geography

[edit]The national park consists of a group of mountain peaks with deep picturesque gorges between them. The highest point of the park is the Kozji Rid peak on the Zvijezda mountain, with 1,591 m (5,220 ft).[4] The most striking of these gorges is the Drina Gorge, with its sheer drops from 1,000 to 250 m (3,280 to 820 ft) and extensive views of western Serbia and nearby Bosnia. It also encompasses the gorges of the rivers Rača, Brusnica and Derventa and the waterfall of Veliki Skakavac on the river Beli Rzav. The area is also characterised by karst caves, pits, springs, and viewing points (Kićak, Smiljevac, Bilješke Stene, Kozje Stene, Vitimirovac and Kozji Rid).[7]

The deepest sections of the Drina canyon are cut on the slopes of the Zvijezda, Tara's natural northwestern extension, sometimes also called High Tara, between the mouths of the Žepa river and Neveljski stream. The canyon is cut in the massive, layered mid-Tertiary limestone deposits. The cliffs are extremely steep, with rock creeps, partially under the vegetation (forests and shrubs) and partially barren. The deepest canyon in Serbia, the Zvijezda Canyon, was discovered only on 12 June 2010. Due to its seclusion and inaccessibility in the bend of the Perućac lake, it is inhabited by bears and chamois. The canyon is located on the right side of the Drina, being completely within the national park area. The stream of Selski Potok flows through it for 25 kilometres (16 mi), down the altitude of 500 metres (1,600 ft) through some 40 waterfalls, varying from 5 to 40 metres (16 to 131 ft). Over the final waterfall, the Selski Potok flows into the Drina.[10]

Plantlife

[edit]

Forests account for three quarters of the national park's area, 160 km2 (62 sq mi), some of them being the best preserved and well-kept in Europe. With 83.5% of the territory under forest, Tara is the most forested area of Serbia and thus nicknamed the "lungs of Serbia". The forest growth is among the highest in Europe: the total wood mass increases each year and the quality of the forest is enhanced. Cutting of the wood is strictly controlled. Since 1960, the total measurement of the wood mass on Tara has been measured every 10 years. From 1990 to 2000, the mass grew from 463.7 m3/ha (5,325 US bushels per acre) to 476.4 m3/ha (5,471 US bushels per acre). Within the park, there are 9 reserves with an area of 29.5 km2 (11.4 sq mi), or 16% of the park, where woodcutting is forbidden. Some of the areas have been left unattended for centuries, making them basically a temperate rainforest.[3][5]

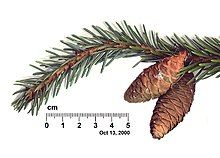

Forests mainly consist of beech, spruce and fir. Tara also boasts a rare endemic Tertiary species, the Serbian spruce which is now protected in the small area of the park. It was discovered by Josif Pančić in 1875 in the Zaovine's hamlet of Đurići. Because of its rarity and scientific importance, it has been placed under national protection as it can only be found on two locations on Tara: the canyon of the Mileševka river and on the Zvezda massif. Oldest trees in the park are the beeches,[3] (some are estimated to be over 500 years old) but other old and rare Tertiary species include European holly, Blagaj's daphne and European yew.[10]

With several other beech localities in the national parks of Fruška Gora and Kopaonik, beech forests Zvezda and Rača Gorge on Tara have been submitted for the inclusion into the UNESCO World Heritage Site Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe in May 2020. The nomination was rejected due to the Serbian laws allowing shelterwood cutting on the area of 5 hectares (12 acres), while UNESCO accepts cut areas no larger than 1 hectare (2.5 acres), and even that is not only in the areas of the highest level of protection, but also in the surrounding zones. It was announced that the rules will be changed, so that parts of Tara might be included in 2023.[11]

In total there are 1,200 plant species in the park, of which 84 are Balkans endemites, and 600 species of fungi. There are two species of edelweiss which can be found in Serbia only on the Tara. Pančić discovered the Derventa knapweed (Centaurea derventana) on the cliffs of the Derventa canyon, while Alpine edelweiss habitats only one ridge on Mokra Gora and is strictly protected. Another endemite is common lady's mantle.[7][12] Other plants include woodland strawberry, wild raspberry and various fungi.[10]

The mountain is known for numerous medicinal plants, including trees, shrubs and herbs, used in folk and modern medicine. Several hundred of them have been described and compiled in assorted manuals and monographies: sessile oak, alder buckthorn, beech, dog rose, black elder, largeleaf linden, black pine, Serbian spruce, common yarrow, couch grass, sticklewort, green-winged orchid, gentiana, greater celandine, European holly, common mallow, coltsfoot, chamomille, lemon balm, oregano, cowslip, comfrey, dandelion, burn nettle, orange mullein.[13]

Wildlife

[edit]

There are total of 140 insect species in the park. Rare species include Pančić's grasshopper (Pyrgomorphella serbica), endemic cricket Balkan isophya discovered in 1882 by Carl Brunner von Wattenwyl and aspen longhorn beetle, which in Serbia lives only on this location. 135 bird species make their temporary or permanent homes on the slopes of the mountain, including golden eagle, griffon vulture, peregrine falcon, Eurasian eagle owl, spotted nutcracker, Eurasian bullfinch, crossbill, black woodpecker, rock partridge and black grouse. On Perućac lake on the Drina, there is a population of common merganser, with 50 pairs. Tara is inhabited by 53 mammalian species, including the protected brown bear and otter, as well as chamois, roe deer, lynx, wolf, jackal, wild boar, European pine marten, and European wildcat.[10][12]

The area where the river Derventa flows into the Drina, is the natural spawning area of the fishes living in the Drina.[14] In total, there are 19 species of fish in the park.[2]

Since they have been fully protected, numbers of brown bears soon began to rise. By 2018, there were over 50, which is considered to be the optimal number of animals on the mountain. As their number grew, despite having feeders they began causing damage to local orchards and apiaries but have not attacked livestock nor the villagers. Some of the animals are tracked via satellite. The tracking shows that females, especially with cubs, occupy a compact area, but males range more widely travelling west, crossing the Drina into Bosnia where hunting is permitted. The bears do not tend to travel into central Serbia, to the east or northeast of the mountain, but the first animal which was tracked used to go all the way to the slopes of the Kopaonik mountain, in the southeast.[15] In April 2019 there were some 60 bears on the Tara, making 80% of the entire brown bear population in Serbia.[16]

In the fall of 2021, a 15-year-old bear named Aleksandar (after Alexander the Great) was equipped with the GPS collar camera. He was specifically selected due to his massive size, as he weighed around 250 kg (550 lb). Footage until August 2022, when he managed to tear the collar, proved that he indeed was an alpha bear on the mountain. Aleksandar was hibernating from mid-November to late March and was quite reluctant to leave the cave. Other animals were hiding from him and moving out of his way so much, that he had no encounters with other animals than bears. He was feeding at the mangers and "enjoyed" spending time with two she-bears in this period, but he mostly was just calmly wandering all over. The bear avoided open spaces, not crossing over the forests' rims. He was extremely cautious to avoid humans, even when close to the villages.[17]

History

[edit]

Work published in May 2018 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America journal by the research team from the Northumbria University revealed that the locality "Crveni Tepih" shows the evidence of the oldest lead pollution in Europe. It is dated to 3600 BC, predating the previous oldest findings dated to 3000 BC in southern Spain and pushed back the origins of lead metallurgy for six centuries.[18][19][20]

Locality Kremenilo, near the village of Višesava, is a prehistoric settlement, dated between 5000 and 7000 BC, as part of the Starčevo culture which developed in Podunavlje as the first agricultural culture in the Balkans.

Mountainous Illyrian tribe of Autariatae inhabited the area during the Bronze Age. Though it is often mentioned that tara means "star" in Sanskrit, name of the mountain is derived from the name of the tribe. On the locality of "Borovo Brdo" near Kaluđerske Bare, a Slavic pottery from the 6th and 7th century was found. The medieval necropolis of Mramorje is located near the village of Perućac. As one of the most important stećci complex in Serbia, it has been protected by the state as a Cultural Monument of Exceptional Importance. Another such necropolis is near the village of Rastište.[12][21] Mramorje is located near the Perućac lake. The necropolis originates rom the 1300s and the 1400s, and currently has 88 visible tombstones. All of them are plain, without ornaments, except for one which is decorated with a circle-shaped ornament. All stones are made of one white limestone block which weight 3 tons and more. They have been called mramorovi ("marble [blocks]"), hence the name of the locality. They are made in different shapes: slab, box, gable roof, slightly dressed rectangular stones, etc. Small scale exploration of the area was conducted in 2010 and the stone monuments were conserved in 2011. Rastište is 7 km (4.3 mi) from Perućac, in the valley of the Derventa river. It consists of two cemeteries, separated by 500 m (1,600 ft), north of the village church. There are 35 tombstones at the Gajevi locality, and 33 at Uroševine. These stećci are decorated with carvings of bow and arrow, swords, etc. It is in the vicinity of the quarry Vagan, the source of the stone for the stećci.[22]

During the Ottoman period, a "Bosnian road" passed through the area. The hamlet of Gradina, near Kremna, was the location of a Turkish arsenal and a caravanserai. They were destroyed by the Austrians in 1738. Due to the heavy forestation, during the Ottoman rule Tara was the hiding place for the hajduks.[12][21] The fort of Solotnik is also located on the mountain.[2]

For a period of time, Tara was an important railway crossroad. Exhibits from that period are kept in the Railway Park "Bela Voda", near the spring of the same name. They include the "maginot railway wagon" for the ammunition transport during the World War I or the German locomotive from 1928. There is also a Railway Museum in Mokra Gora, in the building constructed in 1916 by the Austro‑Hungarians when they were building the narrow gauge railway in occupied Serbia. Known today as the Šargan Eight, it is a heritage railway and a major tourist attraction.[12]

Tourism

[edit]The main tourist points are Kaluđerske Bare on the north, close to Bajina Bašta, and Mitrovac on the south. Hotels Beli Bor and Omorika, as well as several smaller ones, are located on Kaluđerske Bare, while Mitrovac hosts eponymous children's recreation hotel.

The National Park can be reached from Bajina Bašta directly (by the Bajina Bašta - Kaluđerske Bare road), from Perućac via Bajina Bašta (by the Perućac - Mitrovac road) and from Kremna (the Kremna - Kaluđerske Bare road). The Drina gorge, which is an integral part of the park, can be toured by boat.

There is a total of 10 arranged scenic viewpoints, of which Banjska is the most visited.[2] Others include Kićac, Vranovina, Veliki Teferič, Mali Teferič and Vranica.[10] There are 290 kilometres (180 mi) of arranged hiking trails and bicycle paths. On the rivers, there are facilities for kayaking, rafting, board rowing and canyoning.[2]

Locally made items include woolen handcrafts, dairy products, juniper and plum spirits and honey, particularly Pine honey.

Since the mid-2010s, construction of numerous objects on the mountain, in the park and along the lake began. By 2020 there were several thousands of them, vast majority being built illegally, without proper or any permits. Objects include houses, villas and floating barges with houses, with some covering several hundreds of square meters. There is no sewage, so the waste is dropped directly into the lakes, streams and the Drina, while floating garbage covered areas around the barges. In 2018, all but 4 objects along the bank were removed, but in the next two years additional 150 were placed or built. The situation was described as "everyone is having a jurisdiction and no one is having a jurisdiction". Only the management of the national park publicly and officially protested, but neither the state nor the municipal authorities reacted.[14]

Features

[edit]The Rača monastery is a Serbian Orthodox monastery built by king Stefan Dragutin (1276-1282) on the right bank of the Rača river. Three centuries later, a famous scriptorium, known as the School of Rača (Serbian: Рачанска школа, romanized: Račanska škola) developed and flourished in the 16th and 17th century. The monks translated texts from Ancient Greek, wrote histories, and copied manuscripts. They translated and copied not only liturgical but scientific and literary works of the period so the history of Serbian literature is owing a lot to it. Turkish travel writer, Evliya Çelebi noted in his travelogue of 1630 that in Rača Monastery there were 300 monk scribes, who were served by 400 shepherds, blacksmiths, and other staff. The security guard included 200 armed men. It was damaged several times during the Ottoman period. During the Great Turkish War the monastery was partially destroyed by the invading Turks in 1689. In 1826 it was reconstructed due to being burned down several times. Gendarmerie lieutenant colonel Jaraković handed over the Miroslav Gospel to hegumen Platon Milojević in 1941, who kept it during the war. The Rača monastery is declared a cultural monument.[12] Next to the monastery's glebe is the horse ranch and training yard "Dora", opened in 2007.[23]

There are houses on the mountain, representatives of the folk architecture. House of Vukajlović is one of the oldest, built in the middle of the 19th century. It was constructed by Vitor Vukajlović, a meyhane owner from Bajina Bašta. House is not residential anymore and is turned into the tourist facility. It is noted for the writing near the entry doors "Slaviša, with his Mrs. Ana, lodged here in 1905", which is today considered as the oldest date when the tourism on Tara began to develop. Also, there are over 650 shepherd's huts scattered over the mountain, the oldest being from the 1700s. Earlier, there were also specific log cabins, called kućer. Instead on the foundations, they were built on the sledge-type pedestals, so they could be easily moved by the yokes or teams.[12]

A mini hydro was constructed in 1927 on the Vrelo river. It became operational in 1928, powering Bajina Bašta, Perućac and Kaluđerske Bare. The Vrelo is considered the shortest river in Serbia, being only 365 m (1,198 ft) long, which is why it has been nicknamed the "Year". It ends with another attraction, a 8-metre-high (26 ft) waterfall into the Drina, with a lookout and a restaurant above it. This section of the Drina is a starting point of the Drina Regatta, an annual event which grew into a tourist attraction as in July 2017 it was attended by 1,500 vessels with 20,000 people on the boats and 120,000 visitors in total.[12][24]

Next to the Zaovine Lake the photovoltaic solar power plant "Brana Lazići" was built. Location, at an altitude of 880 m (2,890 ft), was chosen in 2014 when the conceptual design was drafted. First 110 kWh (400 MJ) became operational in 2016, with the remaining 220 kWh (790 MJ) added in 2017, bringing the total installed capacity to 330 kWh (1,200 MJ). The plant has 1.152 solar panels covering 5,700 m2 (61,000 sq ft).[25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tara National Park.

- ^ a b c d e Branko Pejović (24 July 2021). Четири деценије Националног парка "Тара" [Four decades of the Tara National Park]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- ^ a b c Branko Pejović (13 July 2008). ""Pluća Srbije" sve jača" (in Serbian). Politika.

- ^ a b "About Tara NP". National Park Tara. 2013.

- ^ a b c "Nacionalni park Tara – položaj, proglašenje nacionalnog parka i zone zaštite" (in Serbian). Geografija.rs. 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Zakon o nacionalnim parkovima (National parks law)" (in Serbian). 5 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Aleksandra Mijalković (18 June 2017), "O očuvanju naše prirodne baštine: najbolja zaštita u naconalnim parkovima", Politika-Magazin (in Serbian), pp. 3–6

- ^ "Usvojen Zakon o nacionalnim parkovima" (in Serbian). Institute for nature conservation of Serbia. October 2015.

- ^ "Proširen Nacionalni park "Tara"" (in Serbian). Turizam & Ugostiteljstvo. 13 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Gradimir Aničić (3 October 2021). Занимљива Србија - Тара : Велики крај - природни рај [Interesting Serbia - Tara : Big area natural paradise]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1253 (in Serbian). pp. 19–21.

- ^ Višnja Aranđelović (10 May 2022). До Унескове листе изменом прописа за фрушкогорске шуме [To UNESCO list through regulations change for Fruška Gora forests]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dimitrije Bukvić (17 July 2017), "Hajdučka planina nad zelenom rekom", Politika (in Serbian), pp. 01 & 08

- ^ Branko Pejović (16 January 2022). "Prirodna apoteka u nedrima Tare" [Natural pharmacy in Tara's bosom]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ^ a b Gradimir Aničić (8 September 2020). "Nacionalna sramota na Perućcu" [National shame in Perućac]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 13.

- ^ Slavica Stuparušić (19 January 2018). "Зими је лакше са медведима" [In winter is easier to deal with bears]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 08.

- ^ Branko Pejović (27–28 April 2019). "Turizam s pogledom na medveda" [Tourism with the bear view]. Politika] (in Serbian). p. 19.

- ^ Branko Pejović (30 October 2022). "Medved s kamerom i njegove devojke" [Bear with camera and his girlfriends]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 21.

- ^ Jovana Nikolić (16 June 2018). "Počeci metalurgije na Balkanu" [Origins of metallurgy in the Balkans]. Politika-Kulturni dodatak (in Serbian). p. 09.

- ^ Jack Longman, Daniel Veres, Walter Finsinger, Vasile Ersek (29 May 2018). "Exceptionally high levels of lead pollution in the Balkans from the Early Bronze Age to the Industrial Revolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Earliest European evidence of lead pollution uncovered in the Balkans". Northumbria University. 29 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Koliko je dugačko Perućačko jezero?", Politika-Da li znate? (in Serbian), p. 38, 12 July 2017

- ^ Branko Pejović (20 July 2019). Светска баштина у Перућцу и Растишту [World heritage in Perućac and Rastište]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 20.

- ^ Branko Pejović (7 September 2020). Дружење с коњима уз манастирски метох [Spending time with horses along the monastery's glebe]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ Branko Pejović (23 July 2017), "Splavari od Sibira do Mokrina", Politika (in Serbian), p. 05

- ^ Соларна електрана на Тари испуњава планове пориѕводње [Solar power plant on Tara works as planned]. Politika (in Serbian). 4 November 2019. p. 10.

Sources

[edit]- Serbia's Wild Side – Mount Tara, Balkan Insight, 20 October 2008, retrieved 11 February 2013

- Tara – Elegantna i nepredvidiva (in Serbian), Vreme, 23 August 2012