Treaty of Tafna

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2009) |

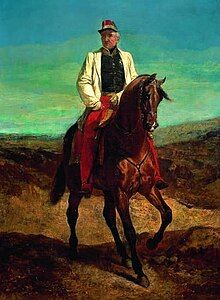

The Treaty of Tafna was signed by both Emir Abdelkader and General Thomas Robert Bugeaud on 30 May 1837.

Context, terms and breakdown

[edit]This agreement was developed after a series of campaigns by French forces into the hinterlands of Algeria, the French under Bugeaud had won a victory against a mixed force of Abdelkader's regular and tribal warriors at the Sikkak river in the summer of 1836, letters between the Emir and the general were exchanged in its aftermath.. While General Clauzel had in 1836 been defeated in a separate theatre of operation in the east of Algeria, this defeat politically required a response and the French War Ministry tasked Bugeaud with achieving peace with the Emir so that limited French forces could avenge the defeat as to avert a loss of face.[1][2]

Other sources[1] emphasise the that the French had undertaken the war partly as a consequence of their dissatisfaction with the terms of the previous treaty with Abdelkader, that had granted him significant control over trade with French enclaves in Algeria. They sought a new arrangement on trade that might increase the profitability of their Algerian possessions, this was of political importance to Marseilles merchants.[1]

The terms of the treaty in French entailed Emir Abdelkader recognizing French imperial sovereignty in Africa, in an arrangement similar to the Regency of Algiers except now with France and not the Ottoman Empire as overlord. In exchange France recognised approximately two thirds of Algeria to Abdelkader (the provinces of Oran, Koléa, Médéa, Tlemcen and Algiers) were ruled by Emir Abdelkader.[3]

In addition to the public contents of the treaty Bugeaud and Abdelkader came to a number of private agreements in addition to the final treaties text. Bugeaud promised the emir modern weapons and to through French force of arms relocate the Dawa’ir and Zmala tribes and exile from Algeria of their chiefs for which Bugeaud received a cash payment which he utilised to support his political career in France spending it to fund roadworks in his constituency.[2]

As a result of the treaty, France maintained its holdings over major ports and while the treaty required all trade by Algeria to pass through these, both French and Algerian traders flouted the terms. Bugeaud initially requested an annual tribute be paid however this was latter dropped in exchange for meaningless concessions.[2]

The French used the peace with Abdelkader to concentrate forces to fight in the east of Algeria successfully to taking Constantine in 1837.

In the aftermath of the treaty Abdelkader consolidated his power over tribes throughout the interior, establishing a capital at Tagdempt far from French control.[2] He worked to motivate the population under French control to resist by peaceful and military means. Seeking to face the French again, he laid claim under the treaty to the Iron gates - a valley that controlled the main route between Algiers and Constantine. When French troops contested the claim in late 1839 by marching through a mountain defile known as the Iron Gates, he claimed a breach of the treaty and renewed calls for jihad.

Analysis of the treaty and its legacy

[edit]There is also controversy about the language Bugeaud inserted into the differing versions of the treaty, in French article one read that Abdelkader ‘recognised the sovereignty of France in Africa’. The Arabic text instead read that "the amir ‘is aware of the rule of French power" (ya‘rifu hukm saltanat firansa) in Africa’. James McDougall argues on the basis of Abdelkader's letters to Bugeaud negotiating the treaty that it cannot have been a translation error and the differing meaning of the texts constitutes duplicity on Bugeaud's part.[2]

'You boast of your power. Are we here under your orders that you should send us such a letter?'

'I have understood your power and all the means at your disposal. We do not doubt it and I well know what harm can be done. Power is in the strength of God who created us all and who protects the weakest.'

— Abdelkader in letters to General Bugeaud

The peace represented a tactical pause in the fighting and by allowing Abdelkader to rebuild his forces after the defeat at the Sikkak river, by allowing this and also Abdelkader to consolidate his control of western Algeria - the French faced a more dangerous enemy latter.[2] However the treaty and his prior military victory did much to burnish the reputation of Bugeaud, who latter while Governor of Algeria would also benefit from the treaties breakdown gaining more plaudits for his military campaign against the Emir.[2]

Naylor argues that the stipulations of the treaty indicated that the French interpreted the territory of Emir Abdelkader as sovereign, thereby recognising an Algerian state.[4]

See also

[edit]- French rule in Algeria

- French Conquest of Algeria

- Emir Abdelkader

- Emir Mustapha

- Thomas Robert Bugeaud

- List of treaties

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Roughton, Richard A. (1 May 1985). "Economic Motives and French Imperialism: The 1837 Tafna Treaty as a Case Study". The Historian. 47 (3): 360–381. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1985.tb00667.x. ISSN 0018-2370.

- ^ a b c d e f g McDougall, James (2017). A History of Algeria (1 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9781139029230.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ An Account of Algeria, or the French Provinces in Africa, p. 116. The subsequent progress of the French army is well known: after meeting with many reverses, and sustaining with great bravery very severe losses, it obtained, by the treaty of Tafna, executed with Abdelkader on 30th May 1837, an acknowledgment on his part of the sovereignty of France in Africa, with a definition of the limits of its dominion in the provinces of Oran and Algiers.

- ^ Naylor, Phillip C. Historical dictionary of Algeria. Scarecrow Press. 2006.

Sources

[edit]- An Account of Algeria, or the French Provinces in Africa. Journal of the Statistical Society of London, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 115 – 126 (March 1839).