Central Tibetan Administration

Central Tibetan Administration བོད་མིའི་སྒྲིག་འཛུགས་ | |

|---|---|

| Motto: བོད་གཞུང་དགའ་ལྡན་ཕོ་བྲང་ཕྱོགས་ལས་རྣམ་རྒྱལ "Tibetan Government, Ganden Palace, Victorious in all Directions" | |

| Anthem: བོད་རྒྱལ་ཁབ་ཆེན་པོའི་རྒྱལ་གླུ "Tibetan National Anthem" | |

| Status | Government-in-exile |

| Capital-in-exile | McLeod Ganj |

| Headquarters | Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh, India, 176215 |

| Official languages | Tibetan |

| Religion | Tibetan Buddhism |

| Government | Presidential republic |

• Sikyong | Penpa Tsering |

• Speaker | Pema Jungney |

| Legislature | Parliament of the Central Tibetan Administration |

| Establishment | 29 May 2011 |

• 17 Point Agreement Rescinded by Tibet | March 1959 |

• Tibet Re-establishes the Kashag | 29 April 1959 |

| 14 June 1991 | |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

Website tibet | |

The Central Tibetan Administration (Tibetan: བོད་མིའི་སྒྲིག་འཛུགས་, Wylie: Bod mi'i sgrig 'dzugs, THL: Bömi Drikdzuk, Tibetan pronunciation: [ˈpʰỳmìː ˈʈìʔt͡sùʔ], lit. 'Tibetan People's Exile Organization')[1] is the Tibetan government in exile, based in Dharamshala, India.[2] It is composed of a judiciary branch, a legislative branch, and an executive branch, and offers support and services to the Tibetan exile community.

The 14th Dalai Lama formally rescinded the 1951 17 Point Agreement with China in early March 1959, as he was escaping Tibet for India. On 29 April 1959, the 14th Dalai Lama in exile re-established the Kashag, which was abolished a month earlier by the Government of the People's Republic of China on 28 March 1959.[3][4][5] He later became permanent head of the Tibetan Administration and the executive functions for Tibetans-in-exile. On 11 February 1991, Tibet became a founding member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) at a ceremony held at the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands.[6] After the 14th Dalai Lama decided no longer to assume administrative authority, the Charter of Tibetans in Exile was updated in May 2011 to repeal all articles relating to his political duties.

The Tibetan diaspora and refugees support the Central Tibetan Administration by voting for members of its parliament, the Sikyong, and by making annual financial contributions through the use of the Green Book. The Central Tibetan Administration also receives international support from other organizations and individuals. The Central Tibetan Administration authors reports, press releases, and administers a network of schools and other cultural activities for Tibetans in India.

Position on Status of Tibet

[edit]In 1963, the 14th Dalai Lama promulgated the Constitution of Tibet, and he became permanent head of state of Tibet.[5] In 1974, the 14th Dalai Lama rejected calls for Tibetan independence,[7] and he became permanent head of the Tibetan Administration and the executive functions for Tibetans-in-exile in 1991. In 2005, the 14th Dalai Lama emphasized that Tibet is a part of China, and Tibetan culture and Buddhism are part of Chinese culture.[8] In March 2011, at 71 years of age, he decided not to assume any political and administrative authority, the Charter of Tibetans in Exile was updated immediately in May 2011, and all articles related to regents were also repealed. In 2017, the 14th Dalai Lama restated that Tibet does not seek independence from China but seeks development.[9]

Funding

[edit]The funding of the Central Tibetan Administration comes mostly from private donations collected with the help of organisations like the Tibet Fund, revenue from the Green Book (the "Tibetan in exile passport")[10] and aid from governments like India and the US.[11][12]

The annual revenue of the Central Tibetan Administration is officially 22 million (measured in US dollars), with the biggest shares going to political activity ($7 million), and administration ($4.5 million).[citation needed] However, according to Michael Backman, these sums are "remarkably low" for what the organisation claims to do, and it probably receives millions more in donations. The CTA does not acknowledge such donations or their sources.[13]

According to a Chinese source, between 1964 and 1968, the U.S. provided 1.735 million dollars to the Dalai Lama's group each year.[14] In October 1998, The Dalai Lama's administration stated that it had received US$1.7 million a year during the 1960s from the Central Intelligence Agency.[15]

In 2002, the Tibetan Policy Act of 2002 was passed in the U.S.[16][17] In 2016, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) awarded a grant of US$23 million to CTA.[18]

In 2017, U.S. president Donald Trump proposed to stop aid to the CTA in 2018.[19] Trump's proposal was criticised heavily by members of the Democratic Party like Nancy Pelosi,[19] and co-chair of the bipartisan Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission, Jim McGovern.[20] In February 2020, at the annual National Prayer Breakfast, Pelosi prayed as Trump attended; "Let us pray for the Panchen Lama and all the Tibetan Buddhists in prison in China or missing for following their faith".[21]

Headquarters

[edit]

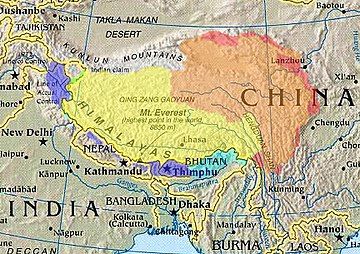

The Central Tibetan Administration is headquartered in McLeod Ganj, Dharamshala, India. It represents the people of the entire Tibet Autonomous Region and Qinghai province, as well as two Tibetan Autonomous Prefectures and one Tibetan Autonomous County in Sichuan Province, one Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture and one Tibetan Autonomous County in Gansu Province and one Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province[22] – all of which is termed "Historic Tibet" by the CTA.

The CTA attends to the welfare of the Tibetan exile community in India, who number around 100,000. It runs schools, health services, cultural activities and economic development projects for the Tibetan community. As of 2003, more than 1,000 refugees still arrive each year from China,[23] usually via Nepal.[24]

Green Book

[edit]Tibetans living outside Tibet can apply at a Central Tibetan Administration office in their country of residence for a personal document called the Green Book, which serves as a receipt book for the person's "voluntary contributions" to the CTA and the evidence of their claims for "Tibetan citizenship".[25]

For this purpose, CTA defines a Tibetan as "any person born in Tibet, or any person with one parent who was born in Tibet." As Tibetan refugees often lack documents attesting to their place of birth, the eligibility is usually established by an interview.[25]

Blue Book

[edit]The Blue Book or Tibetan Solidarity Partnership is a project by Central Tibetan Administration, in which the CTA issues any supporter of Tibet who is of age 18 years or more a Blue Book. This initiative enables supporters of Tibet worldwide to make financial contributions to help the administration in supporting educational, cultural, developmental and humanitarian activities related to Tibetan children and refugees. The book is issued at various CTA offices worldwide.[26]

Internal structure

[edit]

The Central Tibetan Administration currently operates under the "Charter of the Tibetans In-Exile", adopted in 1991, amended in 2011.[27] Executive authority is vested in the Sikyong, an office formerly held by Lobsang Sangay, who was elected in 2011. The Sikyong is supported by a cabinet of Kalons responsible for specific portfolios. Legislative authority is vested in the Parliament of the Central Tibetan Administration.

The Central Tibetan Administration's Department of Finance is made of seven departments and several special offices. Until 2003, it operated 24 businesses, including publishing, hotels, and handicrafts distribution companies.

On 29 April 1959, the Dalai Lama re-established the Kashag. In 1963, he promulgated Constitution of Tibet, and he became permanent head of state of Tibet. In 1974, he rejected calls for Tibetan independence,[7] and he became permanent head of the Tibetan Administration and the executive functions for Tibetans-in-exile in 1991. On 10 March 2011, at 71 years of age, he decided not to assume any political and administrative authority, the Charter of Tibetans in Exile was updated immediately in May 2011, and all articles related to regents were also repealed, and position Sikyong was created.

Kashag

[edit]Notable past members of the Cabinet include Gyalo Thondup, the Dalai Lama's eldest brother, who served as Chairman of the Cabinet and as Kalon of Security, and Jetsun Pema, the Dalai Lama's younger sister, who served variously as Kalon of Health and of Education.[13] Lobsang Nyandak Zayul who served as a representative of the 14th Dalai Lama in the Americas[28] and a multiple cabinet member.[29][30][31] He currently serves as president of The Tibet Fund.[32]

- Penpa Tsering – Sikyong

- Ven Karma Gelek Yuthok – Kalon of Religion & Culture

- Sonam Topgyal Khorlatsang – Kalon of Home

- Karma Yeshi – Kalon of Finance

- Dr. Pema Yangchen – Kalon of Education

- Phagpa Tsering Labrang – Kalon of Security

- Lobsang Sangay – Kalon of Information & International Relations

- Choekyong Wangchuk – Kalon of Health

Settlements

[edit]The Central Tibetan Administration, together with the Indian government, has constructed more than 45 "settlements" in India for Tibetan refugees as of 2020.[33] The establishment of the Tibetan Re-settlement and Rehabilitation (TRR) settlements began in 1966,[34]: 120, 127–131 with the TRR settlements in South India, Darjeeling, and Sikkim becoming officially "protected areas" and requiring special entry permits for entry.[34]: 120

Media activities

[edit]A 1978 study by Melvyn Goldstein and a 1983 study by Lynn Pulman on Tibetan communities-in-exile in southern India argue that the CTA adopted a stance of preserving an "idea of return" and fostering the development of an intense feeling of Tibetan cultural and political nationalism among Tibetans" in order to remain a necessary part of the communities.[35]: 408–410 [34]: 158–159 They state that this was accomplished through the creation of the Tibetan Uprising Day holiday, a Tibetan National Anthem, and the CTA control over local Tibetan-language media that promotes the idea of Chinese endeavours to "eradicate the Tibetan race".[35]: 410–417 [34]: 159–161 From the 1990s onwards, the CTA used Hollywood films in addition to local media to emphasise the Tibetan exile struggle, secure the loyalty of Tibetans both in exile and in Tibet, promote Tibetan nationalism, and foster the CTA's legitimacy to act in the name of the entire Tibetan nation.[36]

Foreign relations

[edit]The Central Tibetan Authority is not recognised as a sovereign government by any country, but it receives financial aid from governments and international organisations for its welfare work among the Tibetan exile community in India.[37][38]

United States

[edit]In 1991, United States President George H. W. Bush signed a Congressional Act that explicitly called Tibet "an occupied country", and identified the Dalai Lama and his administration as "Tibet's true representatives".[39]

In October 1998 the Dalai Lama's administration issued a statement acknowledging the Dalai Lama Group received US$1.7 million a year during the 1960s from the U.S. government through the Central Intelligence Agency,[15] used to train volunteers, run guerrilla operations against the Chinese, and used to open offices and for international lobbying. A guerrilla force was reportedly trained at Camp Hale in Colorado.[40]

During his administration, United States President Barack Obama supported Middle Way Policy of the Central Tibetan Administration[41] and met with the Dalai Lama four times,[42] including at the 2015 annual National Prayer Breakfast.[43]

In 2021, the Biden Administration pledged its support for the CTA, to which a representative expressed gratitude.[44]

See also

[edit]- 2021 Central Tibetan Administration general election

- Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission – defunct body in the Republic of China.

- Mainland Affairs Council

- Ganden Phodrang

- Inner Mongolian People's Party

- Chushi Gangdruk

- Parliament of the Central Tibetan Administration

- Simla Treaty

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Central Tibetan Administration". [Central Tibetan Administration. Archived from the original on 3 August 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ "Tibet dying a 'slow death' under Chinese rule, says exiled leader". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~hpcws/jcws.2006.8.3.pdf Archived 29 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ 外交部:中方从来不承认所谓的西藏"流亡政府" [Ministry of Foreign Affairs: China has never recognized the so-called "government in exile" in Tibet]. 中国西藏网 (in Chinese). 18 March 2016. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ a b 十四世达赖喇嘛. 五洲传播出版社. 1977. ISBN 978-7-80113-298-7.

- ^ "Members". UNPO. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ a b "The Dalai Lama Has Been the Face of Buddhism for 60 Years. China Wants to Change That". Time.

- ^ https://www.cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/dalai-lama-tibet-is-a-part-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china DALAI LAMA: "TIBET IS A PART OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA

- ^ "Tibet wants to stay with China, seeks development: Dalai Lama". The Economic Times.

- ^ McConnell, Fiona (7 March 2016). Rehearsing the State: The Political Practices of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile. John Wiley & Sons. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-118-66123-9.

- ^ Namgyal, Tsewang (28 May 2013). "Central Tibetan Administration's Financial Viability". Phayul. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Central Tibetan Administration (30 June 2011). "Department of Finance". Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ a b Backman, Michael (23 March 2007). "Behind Dalai Lama's holy cloak". The Age. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ 美印出资养活达赖集团 – 世界新闻报 – 国际在线. gb.CRI.cn (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

美国政府的一份解密文件显示,1964至1968年,美国给予达赖集团的财政拨款每年达173.5万美元,其中包括给达赖喇嘛个人津贴18万美元

[A declassified document from the U.S. government shows that from 1964 to 1968, the U.S. financial allocation to the Dalai Group amounted to $1.735 million per year, including a personal allowance of $180,000 to the Dalai Lama.] - ^ a b "World News Briefs; Dalai Lama Group Says It Got Money From C.I.A.". The New York Times. The Associated Press. 2 October 1998. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "Tibetan Policy Act of 2002". 2001-2009.State.gov. US Department of State, Archives. 16 May 2003. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "U.S. government intends to withdraw aid to exiled Tibetans (美政府拟撤销对流亡藏人援助 )". news.dwnews.com (in Chinese). 31 May 2017.

- ^ Samten, Tenzin (5 October 2016). "Grant Funding for the Tibetan Exile Community Thanks to USAID". ContactMagazine.net. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Trump administration makes 'tough choices,' proposes zero aid to Tibetans; wants other countries to follow suit-World News". Firstpost. 26 May 2017. Archived from the original on 26 May 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "McGovern: America Must Stand Up for Human Rights in Tibet". JimMcGovern. 2 May 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Tibet's disappeared Panchen Lama remembered in US National Prayer Breakfast". Tibetan Review. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "Map of Tibet: Under People's Republic of China 1949–2006, The Type of Territorial Sub-Divisions". Tibet.net. Central Tibetan Administration. 22 September 2011. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "India: Information on Tibetan Refugees and Settlements". United States Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services. 30 May 2003. IND03002.ZNY. Retrieved 3 June 2019 – via Refworld.

- ^ "Dangerous Crossing: Conditions Impacting the Flight of Tibetan Refugees // 2003 Update" (PDF). The International Campaign for Tibet. 31 May 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2008.

- ^ a b "China: The 'Green Book' issued to Tibetans; how it is obtained and maintained, and whether holders enjoy rights equivalent to Indian citizenship (April 2006)" (Responses to Information Requests (RIRs)). Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. 28 April 2006. CHN101133.E. Retrieved 3 June 2019 – via Refworld.

- ^ "Blue Book: Frequently Asked Questions (Updated 2020)". Central Tibetan Administration. 30 September 2011.

- ^ "Constitution: Charter of the Tibetans in Exile". Central Tibetan Administration. Archived from the original on 27 January 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ^ Lim, Louisa (21 February 2012). "Protests, Self-Immolation Signs Of A Desperate Tibet". NPR.org. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Halper, Lezlee Brown; Halper, Stefan A. (2014). Tibet: An Unfinished Story. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-936836-5.

- ^ "Finance Kalon speaks on the financial status of the Central Tibetan Administration". Central Tibetan Administration. 6 October 2005. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ "EU Sidesteps Human Rights to Promote Trade, Says Kalon Lobsang Nyandak". Central Tibetan Administration. 28 July 2005. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ "Harford Community College". www.harford.edu. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Punohit, Kunal (24 September 2020). "Tibetan SFF soldier killed on India-China border told family: 'we are finally fighting our enemy'". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

Choglamsar, one of more than 45 "settlements" – special colonies for Tibetan refugees – constructed by the Central Tibetan Authority (CTA), the Tibetan government-in-exile and Indian authorities.

- ^ a b c d Pulman, Lynn (1983). "Tibetans in Karnataka" (PDF). Kailash. 10 (1–2): 119–171.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1978). "Ethnogenesis and resource competition among Tibetan refugees in South India: A new face to the Indo-Tibetan interface". In Fisher, James F. (ed.). Himalayan Anthropology: The Indo-Tibetan Interface. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 395–420.

- ^ Römer, Stephanie (2008). The Tibetan Government-in-Exile: Politics at Large. Routledge. pp. 150–152.

- ^ Staff Reporter (21 January 2020). "US Congress sanctions $9 million fund for strengthening CTA and Tibetan community in exile". Central Tibetan Administration. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ "The Tibet Fund » Links". Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C., The Snow Lion and the Dragon, University of California Press, 1997, p. 119

- ^ Conboy, Kenneth; Morrison, James (2002). The CIA's Secret War in Tibet. Lawrence, Kansas: Univ. Press of Kansas. pp. 85, 106–116, 135–138, 153–154, 193–194. ISBN 978-0-7006-1159-1.

- ^ Staff Reporter. "His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Former US President Barack Obama meet in Delhi, call for action for World Peace". Archived from the original on 3 November 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ Gaphel, Tenzin (4 February 2015). "His Holiness arrives in Washington for annual National Prayer Breakfast".

- ^ Jackson, David (5 February 2015). "Obama praises Dalai Lama at prayer breakfast". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "Biden Administration Promises Continued US Support For Tibet". Radio Free Asia.

Bibliography

[edit]- Roemer, Stephanie (2008). The Tibetan Government-in-Exile. Routledge Advances in South Asian Studies. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-58612-2.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Central Tibetan Administration at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Central Tibetan Administration at Wikimedia Commons

- Central Tibetan Administration

- Politics of Tibet

- Tibet

- Annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China

- Political organisations based in India

- Exile organizations

- Dharamshala

- 1959 establishments in Himachal Pradesh

- Members of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization

- Chinese anti-communists

- Tibet freedom activists

- Governments in exile

- 2021 Central Tibetan Administration general election

- India–Tibet relations

- Freedom of expression organizations

- Civil rights organizations

- Civil liberties advocacy groups

- Human rights

- Human Rights Watch