Syntaxin

| Syntaxin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Structure of an evolutionarily conserved N-terminal domain of syntaxin 1A.[1] | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Syntaxin | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00804 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR006011 | ||||||||

| SMART | SM00503 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1br0 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 197 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 2xhe | ||||||||

| Membranome | 349 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

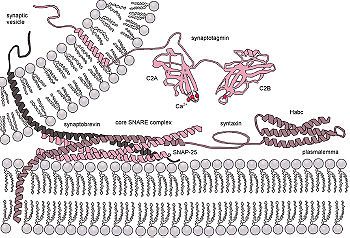

Syntaxins are a family of membrane integrated Q-SNARE proteins participating in exocytosis.[2]

Domains

[edit]Syntaxins possess a single C-terminal transmembrane domain, a SNARE domain (known as H3), and an N-terminal regulatory domain (Habc). Syntaxin 17 may have two transmembrane domains.

- The SNARE (H3) domain binds to both synaptobrevin and SNAP-25 forming the core SNARE complex. Formation of this stable SNARE core complex is believed to generate the free energy required to initiate fusion between the vesicle membrane and plasma membrane.[3]

- The N-terminal Habc domain is formed by 3 α-helices and when collapsed onto its own H3 helix forms an inactive "closed" syntaxin conformation. This closed conformation of syntaxin is believed to be stabilized by binding of Munc-18 (nSec1), although more recent data suggests that nSec1 may bind to other conformations of syntaxin, as well. The "open" syntaxin conformation is the conformation that is competent to form into SNARE core complexes.

Function

[edit]

In vitro syntaxin per se is sufficient to drive spontaneous calcium independent fusion of synaptic vesicles containing v-SNAREs.[5]

More recent and somewhat controversial amperometric data suggest that the transmembrane domain of Syntaxin1A may form part of the fusion pore of exocytosis.[6]

Binding

[edit]Syntaxins bind synaptotagmin in a calcium-dependent fashion and interact with voltage dependent calcium and potassium channels via the C-terminal H3 domain. Direct syntaxin-channel interaction is a suitable molecular mechanism for proximity between the fusion machinery and the gates of Ca2+ entry during depolarization of the presynaptic axonal boutons.

The Sec1/Munc18 protein family is known to bind to Syntaxin and regulate Syntaxins machinery. Munc18-1 binds to Syntaxin 1A via two distinct sites referred as N-terminus binding and "closed" conformation that incorporates both the central Habc domain and the SNARE core domain. Munc18-1 binding to the N-terminus of Syntaxin-1 is thought to facilitate Syntaxin-1 interaction with another SNARE, while binding to the "closed" conformation of Syntaxin-1 is believed to be inhibitory.

Recently published data show that alternative spliced Syntaxin 1 (STX1B) which lacks the transmembrane domain localizes in the nuclei.[7]

Genes

[edit]Human genes encoding syntaxin proteins include:

- STX1A, STX1B, STX2, STX3, STX4, STX5, STX6, STX7, STX8,

- STX10, STX11, STX12, STX16, STX17, STX18, STX19

See also

[edit]- Tomosyn, a syntaxin binding protein

References

[edit]- ^ Fernandez I, Ubach J, Dulubova I, Zhang X, Südhof TC, Rizo J (Sep 1998). "Three-dimensional structure of an evolutionarily conserved N-terminal domain of syntaxin 1A". Cell. 94 (6): 841–9. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81742-0. PMID 9753330.

- ^ Bennett MK, García-Arrarás JE, Elferink LA, Peterson K, Fleming AM, Hazuka CD, Scheller RH (Sep 1993). "The syntaxin family of vesicular transport receptors". Cell. 74 (5): 863–73. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90466-4. PMID 7690687.

- ^ Lam AD, Tryoen-Toth P, Tsai B, Vitale N, Stuenkel EL (2008). "SNARE-catalyzed fusion events are regulated by Syntaxin1A-lipid interactions". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 19 (2): 485–97. doi:10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0148. PMC 2230580. PMID 18003982.

- ^ Georgiev DD, Glazebrook JF (2007). "Subneuronal processing of information by solitary waves and stochastic processes". In Lyshevski SE (ed.). Nano and Molecular Electronics Handbook. Nano and Microengineering Series. CRC Press. pp. 17–1–17-41. doi:10.1201/9781420008142.ch17 (inactive 2024-11-11). ISBN 978-0-8493-8528-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Woodbury DJ, Rognlien K (2000). "The t-SNARE syntaxin is sufficient for spontaneous fusion of synaptic vesicles to planar membranes". Cell Biology International. 24 (11): 809–18. doi:10.1006/cbir.2000.0631. PMID 11067766.

- ^ Han X, Wang CT, Bai J, Chapman ER, Jackson MB (Apr 2004). "Transmembrane segments of syntaxin line the fusion pore of Ca2+-triggered exocytosis". Science. 304 (5668): 289–92. doi:10.1126/science.1095801. PMID 15016962.

- ^ Pereira S, Massacrier A, Roll P, Vérine A, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Poitelon Y, Robaglia-Schlupp A, Jamali S, Roeckel-Trevisiol N, Royer B, Pontarotti P, Lévêque C, Seagar M, Lévy N, Cau P, Szepetowski P (Nov 2008). "Nuclear localization of a novel human syntaxin 1B isoform". Gene. 423 (2): 160–71. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2008.07.010. PMID 18691641.

External links

[edit]- Syntaxin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)