Sherry

| Wine region | |

Jerez-Xérès-Sherry DOP in the province of Cádiz in the region of Andalucía | |

| Official name | D.O.P. Jerez-Xérès-Sherry[1] |

|---|---|

| Type | Denominación de Origen Protegida (DOP) |

| Year established | 1932 |

| Country | Spain |

| No. of vineyards | 6,989 hectares (17,270 acres) |

| Wine produced | 384,350 hectolitres |

| Comments | Data for 2016 / 2017 for Jerez-Xérès-Sherry and Manzanilla S.B. DOPs |

Sherry (Spanish: jerez [xeˈɾeθ]) is a fortified wine made from white grapes that are grown near the city of Jerez de la Frontera in Andalusia, Spain [citation needed]. Sherry is a drink produced in a variety of styles made primarily from the Palomino grape, ranging from light versions similar to white table wines, such as Manzanilla and fino, to darker and heavier versions that have been allowed to oxidise as they age in barrel, such as Amontillado and oloroso. Sweet dessert wines are also made from Pedro Ximénez or Moscatel grapes, and are sometimes blended with Palomino-based sherries.

Under the official name of Jerez-Xérès-Sherry, it is one of Spain's wine regions, a Denominación de Origen Protegida (DOP). The word sherry is an anglicisation of Xérès (Jerez). Sherry was previously known as sack, from the Spanish saca, meaning "extraction" from the solera. In Europe, "sherry" has protected designation of origin status, and under Spanish law, all wine labelled as "sherry" must legally come from the Sherry Triangle, an area in the province of Cádiz between Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, and El Puerto de Santa María.[2] In 1933 the Jerez denominación de origen was the first Spanish denominación to be officially recognised in this way, officially named D.O. Jerez-Xeres-Sherry and sharing the same governing council as D.O. Manzanilla Sanlúcar de Barrameda.[3]

After fermentation is complete, the base wines are fortified with grape spirit to increase their final alcohol content.[4] Wines classified as suitable for aging as fino and Manzanilla are fortified until they reach a total alcohol content of 15.5 percent by volume. As they age in a barrel, they develop a layer of flor—a yeast-like growth that helps protect the wine from excessive oxidation. Those wines that are classified to undergo aging as oloroso are fortified to reach an alcohol content of at least 17 per cent. They do not develop flor and so oxidise slightly as they age, giving them a darker colour. Because the fortification takes place after fermentation, most sherries are initially dry, with any sweetness being added later. Despite the common misconception that sherry is a sweet drink, most varieties are dry.[5][6] In contrast, port wine is fortified halfway through its fermentation, which stops the process so that not all of the sugar is turned into alcohol.

Wines from different years are aged and blended using a solera system before bottling so that bottles of sherry will not usually carry a specific vintage year and can contain a small proportion of very old wine. Sherry is regarded by some wine writers[7] as "underappreciated"[8] and a "neglected wine treasure".[9]

History

[edit]

Jerez has been a centre of viniculture since wine-making was introduced to Spain by the Phoenicians in 1100 BCE. The practice was carried on by the Romans when they took control of Iberia around 200 BCE. The Moors conquered the region in 711 CE and introduced distillation, which led to the development of brandy and fortified wine.

During the Moorish period, the town was called Sherish (a transliteration of the Arabic شريش), from which both sherry and Jerez are derived. Wines similar in style to sherry have traditionally been made in the city of Shiraz in mid-southern Iran, but it is thought unlikely that the name derives from there.[10][11] Wine production continued through five centuries of Muslim rule. In 966, Al-Hakam II, the second Caliph of Córdoba, ordered the destruction of the vineyards, but the inhabitants of Jerez appealed on the grounds that the vineyards also produced raisins to feed the empire's soldiers, and the Caliph spared two-thirds of the vineyards.

In 1264 Alfonso X of Castile took the city. From this point on, the production of sherry and its export throughout Europe increased significantly. By the end of the 16th century, sherry had a reputation in Europe as the world's finest wine.

Christopher Columbus brought sherry on his voyage to the New World and when Ferdinand Magellan prepared to sail around the world in 1519, he spent more on sherry than on weapons.

Sherry became very popular in Great Britain, especially after Francis Drake sacked Cadiz in 1587. At that time Cadiz was one of the most important Spanish seaports, and Spain was preparing an armada there to invade England. Among the spoils Drake brought back after destroying the fleet were 2,900 barrels of sherry that had been waiting to be loaded aboard Spanish ships.[12] This helped popularize sherry in the British Isles.[13]

Because sherry was a major wine export to the United Kingdom, many English companies and styles developed. Many of the Jerez cellars were founded by British families.

In 1894 the Jerez region was devastated by the insect phylloxera. Whereas larger vineyards were replanted with resistant vines, most smaller producers were unable to fight the infestation and abandoned their vineyards entirely.[14]

Types

[edit]- Fino ('delicate' in Spanish) is the driest and palest of the traditional varieties of sherry. The wine is aged in barrels under a cap of flor yeast to prevent contact with the air.

- Manzanilla is an especially light variety of fino sherry made around the port of Sanlúcar de Barrameda.

- Manzanilla Pasada is a Manzanilla that has undergone extended aging or has been partially oxidised, giving a richer, nuttier flavour.

- Amontillado is a variety of sherry that is first aged under flor and then exposed to oxygen, producing a sherry that is darker than a Fino but lighter than an Oloroso. Naturally dry, they are sometimes sold lightly- to medium-sweetened (though these may no longer be labelled as Amontillado).[15]

- Palo Cortado is a variety of sherry that is initially aged like an Amontillado, typically for three or four years, but which subsequently develops a character closer to an Oloroso. This either happens by accident when the flor dies or commonly the flor is killed by fortification or filtration.

- Oloroso ('scented' in Spanish) is a variety of sherry aged oxidatively for a longer time than a Fino or Amontillado, producing a darker and richer wine. With alcohol levels between 18 and 20%, Olorosos are the most alcoholic sherries.[16] Like Amontillado, naturally dry, they are often also sold in sweetened versions called Cream sherry (first made in the 1860s by blending different sherries, usually including Oloroso and Pedro Ximénez).

- Jerez Dulce (sweet sherries) are made either by fermenting dried Pedro Ximénez (PX) or Moscatel grapes, which produces an intensely sweet dark brown or black wine, or by blending sweeter wines or grape must with a drier variety.

On 12 April 2012, the rules applicable to the sweet and fortified Denominations of Origen Montilla-Moriles and Jerez-Xérès-Sherry[17] were changed to prohibit terms such as "Rich Oloroso", "Sweet Oloroso" and "Oloroso Dulce".[18] Such wines are to be labelled as "Cream Sherry: Blend of Oloroso / Amontillado" or suchlike.

The classification by sweetness is:

| Fortified Wine Type | Alcohol % ABV | Sugar content (grams per litre) |

|---|---|---|

| Fino | 15–17 | 0–5 |

| Manzanilla | 15–17 | 0–5 |

| Amontillado | 16–17 | 0–5 |

| Palo Cortado | 17–22 | 0–5 |

| Oloroso | 17–22 | 0–5 |

| Dry | 15–22 | 5–45 |

| Pale Cream | 15.5–22 | 45–115 |

| Medium | 15–22 | 5–115 |

| Cream | 15.5–22 | 115–140 |

| Dulce / Sweet | 15–22 | 160+ |

| Moscatel | 15–22 | 160+ |

| Pedro Ximénez | 15–22 | 212+ |

Protection of sherry

[edit]

Spanish producers have registered the three names Jerez / Xérès / sherry, and so may prosecute producers of similar fortified wines from other places using any of the same names. In 1933, Article 34 of the Spanish Estatuto del Vino (Wine Law) established the boundaries of sherry production as the first Spanish wine denominación. Today, sherry's official status is further recognized by wider EU legislation, under which "sherry" sold within the EU must come from the triangular area of the province of Cádiz between Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, and El Puerto de Santa María. However, the name "sherry" is used as a semi-generic in the United States where it must be labeled with a region of origin such as American sherry or California sherry. However, such wines cannot be exported to the EU.

Both Canadian and Australian winemakers now use the term Apera instead of sherry,[19][20] while consumers still use the term sherry.

Production

[edit]Climate

[edit]The Jerez district has a predictable climate, with approximately 70 days of rainfall and almost 300 days of sun per year. The rain mostly falls between the months of October and May, averaging 600 mm (24 in). The summer is dry and hot, with temperatures as high as 40 °C (104 °F), but winds from the ocean bring moisture to the vineyards in the early morning and the clays in the soil retain water below the surface. The average temperature across the year is approximately 18 °C (64 °F).

Soil

[edit]There are three types of soil in the Jerez district for growing the grapes for sherry:[21]

- Albariza: the lightest soil, almost white, and best for growing Palomino grapes. It is approximately 40 percent chalk, the rest being a blend of clay and sand. Albariza preserves moisture well during the hot summer months.

- Arenas: yellowish soil, also 10 percent chalk but with a high sand content.

- Barros: dark brown soil, 10 percent chalk with a high clay content.

The albariza soil is the best for growing the Palomino grape, and by law, 40 percent of the grapes making up a sherry must come from albariza soil. The barros and arenas soil is mostly used for Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel grapes.

The benefit of the albariza soil is that it can reflect sunlight back up to the vine, aiding it in photosynthesis. The nature of the soil is very absorbent and compact so it can retain and maximize the use of the little rainfall that the Jerez region receives.[21]

Grapes

[edit]Before the phylloxera infestation in 1894, there were estimated to be over one hundred varieties of grape used in Spain for the production of sherry,[22] but now there are only three white grapes grown for sherry-making:

- Moscatel: used similarly to Pedro Ximénez, but it is less common.

- Palomino: the dominant grape used for dry sherries. Approximately 90 per cent of the grapes grown for sherry are Palomino. As varietal table wine, the Palomino grape produces a wine of very bland and neutral characteristics. This neutrality is actually what makes Palomino an ideal grape because it is easily enhanced by the sherry winemaking style.[21]

- Pedro Ximénez: used to produce sweet wines. When harvested these grapes are typically dried in the sun for two days to concentrate their sugars.

Sherry-style wines made in other countries often use other grape varieties.

Fermentation

[edit]The Palomino grapes are harvested in early September, and pressed lightly to extract the must. The must from the first pressing, the primera yema, is used to produce Fino and Manzanilla; the must from the second pressing, the segunda yema, will be used for Oloroso; the product of additional pressings is used for lesser wines, distillation, and vinegar. The must is then fermented in stainless steel vats until the end of November, producing a dry white wine with 11–12 per cent alcohol content. Previously, the fermentation and initial aging were done in wood; now it is almost exclusively done in stainless steel, with the exception of one or two high-end wines.

Fortification

[edit]Immediately after fermentation, the wine is sampled and the first classification is performed. The casks are marked with the following symbols according to the potential of the wine:

| / | a single stroke indicates a wine with the finest flavour and aroma, suitable for Fino or Amontillado. These wines are fortified to about 15 per cent alcohol to allow the growth of flor. |

|---|---|

| /. | a single stroke with a dot indicates a heavier, more full-bodied wine. These wines are fortified to about 17.5 per cent alcohol to prevent the growth of flor, and the wines are aged oxidatively to produce Oloroso. |

| // | a double stroke indicates a wine that will be allowed to develop further before determining whether to use the wine for Amontillado or Oloroso. These wines are fortified to about 15 per cent alcohol. |

| /// | a triple stroke indicates a wine that has developed poorly and will be distilled. |

The sherry is fortified using destilado, made by distilling wine, usually from La Mancha. The distilled spirit is first mixed with mature sherry to make a 50/50 blend known as mitad y mitad (half and half), and then the mitad y mitad is mixed with the younger sherry to the proper proportions. This two-stage procedure is performed so the strong alcohol will not shock the young sherry and spoil it.[23]

Aging

[edit]

The fortified wine is stored in 500-litre casks made of North American oak, which is more porous than French or Spanish oak. The casks, or butts, are filled five-sixths full, leaving "the space of two fists" empty at the top to allow flor to develop on top of the wine.

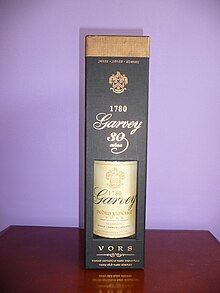

Sherry is then aged in the solera system where new wine is put into wine barrels at the beginning of a series of three to nine barrels. Periodically, a portion of the wine in a barrel is moved into the next barrel down, using tools called the canoa (canoe) and rociador (sprinkler) to move the wine gently and avoid damaging the layer of flor in each barrel. At the end of the series, only a portion of the final barrel is bottled and sold. Depending on the type of wine, the portion moved may be between five and thirty percent of each barrel. This process is called "running the scales" because each barrel in the series is called a scale. Thus, the age of the youngest wine going in the bottle is determined by the number of barrels in the series, and every bottle also contains some much older wine than is stated. Sherry is aged in the solera for a minimum of two years.[24] A large solera system may consist of scales that require more than one barrel to hold. The word 'solera' means 'on the ground'; this refers to the stacking system that was, and sometimes still is, used, with the youngest barrels at the top and the oldest scale, also somewhat ambiguously called 'the solera', at the bottom. Of late, sherry producers and marketers have been bottling their wines en rama, with only a light filtration, and often a selection of a favored barrel from a larger solera. Such sherries can be considerably more complex in flavour than the standard bottlings, and, according to many, are worth seeking out.[25] In order to allow the sale of reliable average age-dated sherries, the regulating council has set up a system that accurately tracks the average age of the wines as they move through their solera. Two average age-dated categories are recognized: VOS ('Vinum Optimum Signatum' – 20 years old average age minimum) and VORS ('Vinum Optimum Rare Signatum' – 30 years old average age minimum).[26]

Sherry-seasoned casks are sold to the Scotch whisky industry for use in aging whisky.[27] Other spirits and beverages may also be aged in used sherry casks. Contrary to what most people think, these sherry-seasoned casks are specifically prepared for the whisky industry, they are not the same as the old (and largely inactive) butts used for the maturation of sherry.[28]

Storing and drinking

[edit]Once bottled, sherry does not generally benefit from further aging and may be consumed immediately, though the sherries that have been aged oxidatively may be stored for years without noticeable loss in flavour. Bottles should be stored upright to minimize the wine's exposed surface area. As with other wines, sherry should be stored in a cool, dark place. The best fino sherries, aged for longer than normal before bottling, such as Manzanilla Pasada, will continue to develop in the bottle for some years.

Fino and Manzanilla are the most fragile types of sherry and should usually be drunk soon after opening, in the same way as unfortified wines. In Spain, Finos are often sold in half bottles, with any remaining wine being thrown out if it is not drunk the same day it is opened.[29] Amontillados and Olorosos will keep for longer, while sweeter versions such as PX, and blended cream sherries, are able to last several weeks or even months after opening since the sugar content acts as a preservative.

Sherry is traditionally drunk from a copita (also referred to as a catavino), a special tulip-shaped sherry glass. Sampling wine directly from a sherry butt may be performed with a characteristic flourish by a venenciador, named after the special cup (the venencia) traditionally made of silver and fastened to a long whale whisker handle. The cup, narrow enough to pass through the bung hole, withdraws a measure of sherry which is then ceremoniously poured from a head height into a copita held in the other hand.[30]

Various types are often mixed with lemonade (and usually ice). This long drink is now called Rebujito. A similar drink in the Victorian era was the sherry cobbler, shaken and served over shaved ice.[31]

In popular culture

[edit]

Many literary figures have written about sherry, including William Shakespeare, Benito Pérez Galdós,[32] and Edgar Allan Poe (in his story "The Cask of Amontillado").

Brothers Frasier and Niles Crane frequently consume sherry on the TV sitcom Frasier.[33]

In the UK television show Yes Minister, Jim Hacker frequently drinks sherry with Sir Humphrey Appleby and Bernard Woolley in his office.

Sherry, and Amontillado specifically, is heavily featured in season 3, episode 10 of Monty Python's Flying Circus.

Sherry is frequently mentioned in the novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, and plays an important role in the narrative: the spy Jim Prideaux is alerted to the presence of a double agent within his division when Russian KGB agents are able to correctly identify the brand of sherry that was consumed during a secret meeting of MI6 personnel.

In John Mortimer's long-running Rumpole of the Bailey book and television series, Horace Rumpole continually complains about how various family doctors are served sherry by his wife Hilda when they visit. For example, in 'Rumpole and the Boat People':

Dr MacClintock, the slow-speaking, Edinburgh-bred quack to whom my wife, Hilda turns in times of sickness, took a generous gulp of the sherry she always pours him when he visits our mansion flat, (It's lucky that all his N.H.S. patients aren't so generous or the sick of Gloucester Road would be tended by a reeling medico, yellow about the gills and sloshed on amontillado.)

The historic sherry cellars have given rise to a breed of Spanish dog, the Andalusian wine-cellar rat-hunting dog, and iconic bull posters used to advertise sherry.

The film Withnail and I features a much-quoted scene where the two protagonists are offered sherry by the lecherous Uncle Monty.

Related products

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Denominación de Origen Protegida "Jerez-Xérès-Sherry"". mapa.gob.es. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ "Quality Control – Vintage Direct". Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ "Foods and Wines from Spain. Everything you should know about Spanish food, Spanish wine and gastronomy from Spain". foodswinesfromspain.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2009.

- ^ "Classification and Fortification". sherry.org. Regulatory Council of Sherry Wines. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ Lyons, Will (12 August 2015). "The Aperitif for Every Season". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 13 August 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ Dao, Dan Q (29 June 2023). "A Guide to Sherry Varieties: Everything You Need to Know About Spain's Famed Fortified Wine". Serious Eats. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ Eric Asimov, "For Overlooked Sherries, Some Respect" Archived 1 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 9 July 2008.

- ^ Karen MacNeil (2001), The Wine Bible (Workman Publishing, ISBN 978-1-56305-434-1), 537: "the world's most misunderstood and underappreciated wine".

- ^ Jancis Robinson, Sherry Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine (5 September 2008): "The world's most neglected wine treasure".

- ^ Maclean, Fitzroy. Eastern Approaches. (1949). Reprint: The Reprint Society Ltd., London, 1951, p. 215

- ^ William Bayne Fisher (1 October 1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-521-06935-9. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ^ Johnson, Hugh (2005). The story of wine (New illustrated ed.). London: Octopus Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-84000-972-9.

- ^ Juan P. Simó (28 November 2010). "Me habré bebido El Majuelo". diariodejerez.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 August 2011..

- ^ Unwin, Tim (1991). Wine and the vine: an historical geography of viticulture and the wine trade (1st ed.). London: Routledge. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-415-03120-2.

- ^ "Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía (BOJA)" (PDF). 12 April 2012. p. 52.

- ^ T. Stevenson The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia pg 325 Dorling Kindersley 2005 ISBN 978-0-7566-1324-2

- ^ "Pliego de Condiciones de la Denominación de Origen "Jerez-Xérès-Sherry"" [Specification of Conditions for the Designation of the Origin of "Jerez-Xérès-Sherry"] (PDF). sherry.org. Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. 30 November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013.

- ^ "Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía (BOJA) Página núm. 52 BOJA núm. 71 Sevilla, 12 de abril 2012 – The Andalusia Government Official Bulletin Number 71, Page 5" (PDF).

- ^ Fairfax Regional Media (19 January 2009). "Apera it is as sun sets on sherry". The Border Mail. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ "Where did the term 'Apera', which has replaced the term for 'Sherry' made in Canada, come from?". Wine Spectator.

- ^ a b c K. MacNeil The Wine Bible pg 438 Workman Publishing 2001 ISBN 1-56305-434-5

- ^ T. Stevenson, ed. The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia (3rd Edition)

- ^ "Jerez de la Frontera Sherry Wine Tours from Seville | Spanish Fiestas". spanish-fiestas.com. 8 October 2020.

- ^ https://www.sherry.wine/sites/default/files/pliego_de_condiciones_de_la_do_jerez-xeres-sherry.pdf Archived 21 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, art. C3 c)

- ^ Liem, Peter and Barquín, Jesús, Sherry, Manzanilla, and Morilla, a guide to the traditional wines of Andalusia, New York: Mantius, 2012.

- ^ "Age statements: VOS / VORS sherry". sherrynotes.com. 25 February 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Types of Sherry Cask Used To Make Whisky, And Their Effect on Flavour". TopWhiskies. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Sherry and oak". 6 September 2016.

- ^ K. MacNeil The Wine Bible pg 447 Workman Publishing 2001. ISBN 978-1-56305-434-1

- ^ Julyan, Brian K. (26 December 2008). Sales and Service for the Wine Professional. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781844807895 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Time for a Drink: Sherry Cobbler". Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ "Literatura del Jerez: Benito Pérez Galdós y el Jerez" [Sherry Literature: Benito Pérez Galdós and Sherry]. jerezdecine.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- ^ "What kind of sherry did Frasier drink?". Henry's World of Booze. 3 November 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Jeffs, Julian (1 September 2004). Sherry (5th rev. ed.). London: Mitchell Beazley. ISBN 978-1-84000-923-1. OL 8908486M. Retrieved 25 August 2011.