Stereotypes of East Asians in the United States

Stereotypes of East Asians in the United States are ethnic stereotypes found in American society about first-generation immigrants and their American-born descendants and citizenry with East Asian ancestry or whose family members who recently emigrated to the United States from East Asia, as well as members of the Chinese diaspora whose family members emigrated from Southeast Asian countries. Stereotypes of East Asians, analogous to other ethnic and racial stereotypes, are often erroneously misunderstood and negatively portrayed in American mainstream media, cinema, music, television, literature, video games, internet, as well as in other forms of creative expression in American culture and society. Many of these commonly generalized stereotypes are largely correlative to those that are also found in other Anglosphere countries, such as in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, as entertainment and mass media are often closely interlinked between them.

Largely and collectively, these stereotypes have been internalized by society and in daily interactions, current events, and government legislation, their repercussions for Americans or immigrants of East Asian ancestry are mainly negative.[1][2] Media portrayals of East Asians often reflect an Americentric perception rather than authentic depictions of East Asian cultures, customs, traditions, and behaviors.[1] East Asian Americans have experienced discrimination and have been victims of bullying and hate crimes related to their ethnic stereotypes, as it has been used to reinforce xenophobic sentiments.[1][3] Notable fictional stereotypes include Fu Manchu and Charlie Chan, which respectively represents a threatening, mysterious East Asian character as well as an apologetic, submissive, "good" East Asian character.[4]

East Asian American men are often stereotyped as physically unattractive and lacking social skills.[5] This contrasts with the common view of East Asian women being perceived as highly desirable relative to their white female counterparts, which often manifests itself in the form of the Asian fetish, which has been influenced by their portrayals as hyper-feminine "Lotus Blossom Babies", "China dolls", "Geisha girls", and war brides.[6] In media, East Asian women may be stereotyped as exceptionally feminine and delicate "Lotus Blossums", or as Dragon Ladies, while East Asian men are often stereotyped as sexless or nerdy.[7]

East Asian mothers are also stereotyped as tiger moms, who are excessively concerned with their child's academic performance. This is stereotypically associated with high academic achievement and above-average socioeconomic success in American society.[8][9]

Exclusion or hostility

[edit]Yellow Peril

[edit]The term "Yellow Peril" refers to white apprehension in the core Anglosphere countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United States, first peaking in the late 19th-century. Such perilism stems from a claim that whites would be "displaced" by a "massive influx of East Asians"; who would fill the nation with a "foreign culture" and "speech incomprehensible" to those already there and "steal jobs away from the European inhabitants" and that they would eventually "take over and destroy their civilization, ways of life, culture and values."

The term has also referred to the belief and fear that East Asian societies would "invade and attack" Western societies, "wage war with them" and lead to their "eventual destruction, demise and eradication." During this time, numerous anti-Asian sentiments were expressed by politicians and writers, especially on the West Coast, with headlines like "The 'Yellow Peril'" (Los Angeles Times, 1886) and "Conference Endorses Chinese Exclusion" (The New York Times, 1905)[10] and the later Japanese Exclusion Act. The American Immigration Act of 1924 limited the number of Asians because they were considered an "undesirable" race.[11]

Laws in other Anglosphere countries

[edit]Australia had similar fears and introduced a White Australia policy, restricting immigration between 1901 and 1973, with some elements of the policies persisting up until the 1980s. On February 12, 2002, Helen Clark, then prime minister of New Zealand apologized "to those Chinese people who had paid the poll tax and suffered other discrimination, and to their descendants". She also stated that Cabinet had authorized her and the Minister for Ethnic Affairs to pursue with representatives of the families of the early settlers a form of reconciliation which would be appropriate to and of benefit to the Chinese community.[12]

Similarly, Canada had in place a head tax on Chinese immigrants to Canada in the early 20th century; a formal government apology was given in 2007 (with compensation to the surviving head tax payers and their descendants).[13]

Perpetual foreigner

[edit]There is a widespread perception that East Asians are not considered genuine Americans but are instead "perpetual foreigners".[3][14][15] Asian Americans often report being asked the question, "Where are you really from?" by other Americans, regardless of how long they or their ancestors have lived in United States and been a part of its society.[16]

East Asian Americans have been perceived, treated, and portrayed by many in American society as "perpetual" foreigners who are unable to be assimilated and inherently foreign regardless of citizenship or duration of residence in the United States.[17][18] A similar view has been advanced by Ling-chi Wang, professor emeritus of Asian American studies at the University of California, Berkeley. Wang asserts that mainstream media coverage of Asian communities in the United States has always been "miserable".[19] He states, "In [the] mainstream media's and policymakers' eyes, Asian Americans don't exist. They are not on their radar... and it's the same for politics."[19]

I. Y. Yunioshi from Blake Edwards' 1961 American romantic-comedy Breakfast at Tiffany's is one such example which had been broadly criticized by mainstream publications. In 1961, The New York Times review said that "Mickey Rooney's bucktoothed, myopic Japanese is broadly exotic."[20] In 1990, The Boston Globe criticized Rooney's portrayal as "an irascible bucktoothed nerd and an offensive ethnic caricature".[21] Critics note that the character of Mr. Yunioshi reinforced anti-Japanese wartime propaganda to further exclude Japanese Americans from being treated as normal citizens, rather than hated caricatures.[22][23]

A study by UCLA researchers for the Asian American Justice Center (AAJC), Asian Pacific Americans in Prime Time, found that Asian-American actors were underrepresented on network TV. While Asian-Americans make up 5 percent of the US population, the report found only 2.6 percent were primetime TV regulars. Shows set in cities with significant Asian populations, like New York and Los Angeles, had few East Asian roles. The lack of East Asian representation in American film and theater supports the argument that they are still perceived as foreigners.[24]

East Asian women

[edit]East Asian women have long been fetishized as highly desirable by white men, and studies have shown that they are the most desired women in the Western world, and are considered the most physically attractive.[25][26][27][28][29]

Some scholars believe that modern stereotypes of Asian women's sexuality may trace their roots to European colonialism and overseas military intervention. Overseas soldiers saw East and Southeast Asian women as physically and sexually superior to white women.[30] East Asian women were stereotyped as extremely seductive and sinister. and this stereotype was so alarming that nationalist politicians sought to ban Asian women from entering the United States.[31] The 1875 Page Act was passed, banning Chinese women from entering the United States, to prevent married white men from falling to the temptation to cheat on their wives with Asian women.[31][32]

During the occupation of Japan by the U.S. military, American soldiers came to view Japanese women as superior to American women. Among U.S. soldiers, it was said that the heart of a Japanese woman was "twice as big" as an American woman's; reflecting the stereotype that Asian women are more feminine than Western women.[33]

Food

[edit]Food from Chinese restaurants in the United States is often claimed to be unsafe due to contamination of Chinese-imported food or the use of monosodium glutamate, the latter of which putatively causes a condition known as Chinese restaurant syndrome, and food scares in China often receive heightened attention in Western media.[34][35] Asians are also stereotyped as eating animals unusual for consumption in the US such as cats and dogs, or even stealing pets for consumption, despite the declining consumption in China.[36][37] This notion was amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic, with US Senator John Cornyn characterizing the country in March 2020 as "a culture where people eat bats and snakes and dogs and things like that".[38][39]

Model minority

[edit]East Asians in the United States have been stereotyped as a "model minority"; where as a collective group have achieved an above average socioeconomic performance and standing compared to other ethno-racial groups in United States while possessing positive traits such as being seen as being conscientious, industrious, disciplined, persistent, driven, studious, and intelligent people who have elevated their socioeconomic status through merit, persistence, tenacity, self-discipline, drive, and diligence. The model minority construct is typically measured by their above average levels of educational attainment, representation in white-collar professional and managerial occupations, and household incomes relative to other ethno-racial groups in the United States.[40]

Generalized statistics and positive socioeconomic indicators of East Asian Americans are often cited to back up the model minority image include the high likelihoods and probabilities of East Asian Americans of getting into an elite American university in addition to possessing above average educational qualifications and attainment rates (30% of National Merit Scholarships are awarded to Asian Americans[41]), high representation in professional occupations such as academia, financial services, high technology, law,[42] management consulting, and medicine,[43] coupled with a higher household income than other racial groups in the United States. East Asians are most often perceived to achieve a higher degree of socioeconomic success than the U.S. population average. As well, other socioeconomic indicators are used to support this argument, such as low poverty rates, low crime rates, low illegitimacy rates, low rates of welfare dependency, and lower divorce rates coupled with higher family stability. However, though East Asian Americans have a higher median income than most other ethno-racial in the United States, they also have a larger income gap than any other ethno-racial group.[44] However, the indicators fail to reflect the diversity of the East Asian community as a whole. According to a report for the Ascend Foundation, whilst the probability of East Asians getting hired for high-tech employment opportunities is high, East Asian Americans as a collective racial group also have the lowest probability of earning a management promotion while climbing the ladders of corporate America.[45] This is also reflected in the under representation of Asian American lawyers in leadership and management roles.[42]

Issues with the label

[edit]However, some East Asian Americans believe the model minority image to be damaging and inaccurate and are acting to dispel this stereotype.[46] Some have said that the model minority myth may perpetuate and trigger a denial of Asian Americans' racial reality, which happens to also be one of eight themes that emerged in a study of commonly experienced Asian American microaggressions.[47] Many scholars, activists, and most major American news sources have started to oppose this stereotype, calling it a misconception that exaggerates the socioeconomic success of East Asian Americans.[48][49][50][51][52] According to Kevin Nguyen Do, the portrayal of the model minority image in American media has created negative psychological impacts such as stress, depression and anxiety and can lead to increased levels of depersonalization. This is because the model minority image in film is usually coupled with negative characteristics of a personality such as being obedient, nerdy and unable to express a sexual or romantic longing.[53]

According to those critical of this belief, the model minority stereotype also alienates other Asian American subgroups, such as Southeast Asian Americans, where many of whom hail from far less affluent Asian countries than their East Asian American counterparts and covers up existing Asian American issues and needs that are not properly addressed in American society at large.[54][55][56][57] Additionally, the stereotypical view that East Asians are generally socioeconomically successful obscures other disadvantages that East Asians generally face, especially in a comparative sense with regards to their fellow East Asian American counterparts who do not fit the standard model minority mold and are less socioeconomically successful.[47] For example, the widespread notion that East Asian Americans are overrepresented at elite Ivy League and other prestigious American universities, have higher educational attainment rates, constitute a large presence in professional and managerial occupations and earn above average per capita incomes obscures workplace issues such as the "bamboo ceiling" phenomenon, where the advancement in corporate America where attaining the highest-level managerial and top-tiered executive positions at major American corporations reaches a limit,[58][59][60] and the fact that East Asians must acquire more education, possess work experience, and have to work longer hours than their white American counterparts to earn the same amount of money.[57]

The "model minority" image is also seen as being damaging to East Asian American students because their generalized socioeconomic success makes it easy for American educators to overlook other East Asian American students who are less socioeconomically successful, less achieving, struggle academically, and assimilate more slowly in the American school system.[2] Some American educators hold East Asian American students to a higher academic standard and ignore other students of East Asian ancestry with learning disabilities from being given attention that they need. This may deprive those students being encumbered with negative connotations of being a model minority and labeled with the unpopular Hollywood "nerd" or "geek" image.[61]: 223

Due to this image, East Asian Americans have been the target of harassment, bullying, and racism from other racial groups due to the racially divisive model minority stereotype.[62]: 165 In that way, the model minority does not protect Asian Americans from racism.[63] The myth also undermines the achievements of East Asian American students who are erroneously perceived largely on part of their inherent racial attributes, rather than other factoring extraneous characteristics such as a strong work ethic, tenacity and discipline.[64][65][66] The pressures to achieve and live up to the model minority image have taken a mental and psychological toll on some East Asian Americans as studies have noted a spike in prescription drug abuse by East Asian Americans, particularly students.[67] The pressures to achieve and live up to the model minority image have taken a mental and psychological toll on East Asian Americans.[68] Many have speculated that the use of illegal prescription drugs have been in response to East Asian Americans' pressure to succeed academically.[68]

East Asian Americans also commit crimes at disproportionately lower rates than other racial and ethnic groups in the United States despite having a younger average age and higher family stability.[69][70][71] Research findings have shown that Asian American offenders are sometimes given more lenient punishments.[72] Occasionally however, such extraordinarily rare exceptions involving individual East Asian American criminals do receive widespread media coverage. Such vanishingly rare exceptional occurrences include the infamous Han Twins Murder Conspiracy in 1996, and the 1996 United States campaign finance controversy where several prominent Chinese American businessmen were convicted of violating various campaign finance laws. Other incidents include the shooting rampage by physics student Gang Lu at the University of Iowa in 1991 and Norman Hsu, a Wharton School graduate, businessman and former campaign donor to Hillary Clinton who was captured after being a fugitive for sixteen years for failing to appear at a sentencing for a felony fraud conviction. Other examples of criminal and unethical behavior are in contrast to the artificially standardized model minority construct.[73][74]

One notable case was the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre committed by the Korean-American mass murderer, Seung-Hui Cho, which led to the deaths of 33 individuals, including the eventual suicide of Cho himself. The shooting spree, along with Cho's Korean ancestry, stunned American society.[75] Other notable cases include the downfall of politician Leland Yee from serving in the California State Senate to serving time in federal prison, and NYPD Officer Peter Liang, who was convicted of shooting an unarmed black man. Some viewed Officer Liang as being privileged by "adjacent whiteness",[76] while Jenn Fang argues that his fate "proves that the benefits of 'model minority' status are in fact transient—and easily revoked."[77]

Another effect of the stereotype is that American society at large may tend to ignore the underlying racism and discrimination that many East Asian Americans still face despite possessing above-average socioeconomic indicators and exhibiting positive statistical profiles. Complaints are dismissed by American politicians and other government legislators with the claim that the racism that many East Asian Americans still face is less important than or not as bad as the racism faced by other minority racial groups, thus establishing a systematically deceptive racial hierarchy. Believing that due to their archetypal socioeconomic success by fitting East Asian Americans in artificial model minority mold and that they possess so-called "positive" stereotypical attributes and traits, leading many ordinary Americans to assume that East Asian Americans face no absolute forms of racial discrimination or social issues in American society at large, and that their community is thriving, having "gained" their socioeconomic success through their own merits.[78][79]

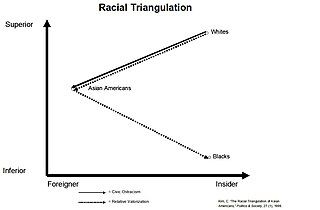

Racial triangulation theory

[edit]

Both the "model minority" stereotype and the "perpetual foreigner" stereotype contribute to the theory of "racial triangulation" proposed by political scientist Claire Jean Kim. With many previous discussions of race focusing solely on a "Black vs. white" dichotomy, Kim proposes that Asian Americans "have been racialized relative to and through interaction with Whites and Blacks."[80] The theory states that racial triangulation occurs through two processes, both of which ultimately reinforce existing racial power structures. First, Asians are "valorized" relative to Blacks. This is aided by the "model minority" stereotype, "citing Asians' hard work ethic and material successes and implying deficiencies in the latter."[81] Second, Asians are ostracized and deemed "immutably foreign and unassimilable with Whites."[80] This second process is aided by the "perpetual foreigner" stereotype, which reinforces a belief that Asians are inherently alien and apolitical. However Kim also notes that many Westerners do see Asians as easily integrated, with the caveat that their ability to be normalized is markedly gendered, with Asian women being seen as ideal immigrants.[82]

Stereotypes in American fiction

[edit]Dr. Fu Manchu and Charlie Chan are two well-known fictional East Asian characters in America's cultural history. Created by Sax Rohmer and Earl Derr Biggers, respectively, in the early part of the 20th century, Dr. Fu Manchu is the embodiment of America's imagination of a threatening, mysterious East Asian while Charlie Chan is an apologetic, submissive Chinese-Hawaiian-American detective who represents America's archetypal "good" East Asian. Both characters found widespread popularity in numerous novels and films.[4]

Dr. Fu Manchu

[edit]

Thirteen novels, three short stories, and one novella have been written about Dr. Fu Manchu, the villainous Chinese mastermind. Millions of copies have been sold in the United States with publication in American periodicals and adaptations to film, comics, radio, and television. Due to his enormous popularity, the "image of Fu Manchu has been absorbed into American consciousness as the archetypal East Asian villain."[4] In The Insidious Doctor Fu-Manchu, Sax Rohmer introduces Dr. Fu Manchu as a cruel and cunning man, with a face like Satan, who is essentially the "Yellow Peril incarnate".[83]

Sax Rohmer inextricably tied the evil character of Dr. Fu Manchu to all East Asians as a physical representation of the Yellow Peril, attributing the villain's evil behavior to his race. Rohmer also adds an element of mysticism and exoticism to his portrayal of Dr. Fu Manchu. Despite Dr. Fu Manchu's specifically Manchu ethnicity, his evil and cunning are pan-Asian attributes, again reinforcing Dr. Fu Manchu as representational of all East Asian people.[4]

Blatantly racist statements made by white protagonists such as: "the swamping of the white world by yellow hordes might well be the price of our failure" again add to East Asian stereotypes of exclusion.[84] Dr. Fu Manchu's inventively sardonic methods of murder and white protagonist Denis Nayland Smith's grudging respect for his intellect reinforce stereotypes of East Asian intelligence, exoticism/mysticism, and extreme cruelty.[4][85]

Charlie Chan

[edit]

Charlie Chan, a fictional character created by author Earl Derr Biggers loosely based on Chang Apana (1871–1933), a real-life Chinese-Hawaiian police officer, has been the subject of 11 novels (spanning from 1925 to as late as 2023), over 40 American films, a comic strip, a board game, a card game, and a 1970s animated television series. In the films, the role of Charlie Chan has usually been played by white actors (namely Warner Oland, Sidney Toler, and Roland Winters).[86] This is an example of "whitewashing", where white actors play the characters of non-white roles.[87] White actors who have played the role of Charlie Chan were covered in "yellowface" makeup and spoke in broken English.[87]

In stark contrast to the Chinese villain Dr. Fu Manchu, East Asian-American protagonist Charlie Chan represents the American archetype of the "good" East Asian.[4] In The House Without a Key, Earl Derr Biggers describes Charlie Chan in the following manner: "He was very fat indeed, yet he walked with the light dainty step of a woman. His cheeks were chubby as a baby's, his skin ivory tinted, his black hair close-cropped, his amber eyes slanting."[88] Charlie Chan speaks English with a heavy accent and flawed grammar, and is exaggeratedly polite and apologetic. After one particular racist affront by a Bostonian woman, Chan responds with exaggerated submission, "Humbly asking pardon to mention it, I detect in your eyes slight flame of hostility. Quench it, if you will be so kind. Friendly co-operation are essential between us." Bowing deeply, he added, "Wishing you good morning."[88]

Because of Charlie Chan's emasculated, unassertive, and apologetic physical appearance and demeanor he is considered a non-threatening East Asian man to mainstream audiences despite his considerable intellect and ability. Many modern critics, particularly Asian-American critics, claim that Charlie Chan has none of the daring, assertive, or romantic traits generally attributed to white fictional detectives of the time,[89] allowing "white America ... [to be] securely indifferent about us as men."[90] Charlie Chan's good qualities are the product of what Frank Chin and Jeffery Chan call "racist love", arguing that Chan is a model minority and "kissass".[91] Instead, Charlie Chan's successes as a detective are in the context of proving himself to his white superiors or white racists who underestimate him early on in the various plots.[4]

The Chan character also perpetuates stereotypes as well, oft quoting supposed ancient Chinese wisdom at the end of each novel, saying things like: "The Emperor Shi Hwang-ti, who built the Great Wall of China, once said: 'He who squanders to-day talking of yesterday's triumph, will have nothing to boast of tomorrow.'"[92] Fletcher Chan, however, argues that the Chan of Biggers's novels is not subservient to whites, citing The Chinese Parrot as an example; in this novel, Chan's eyes blaze with anger at racist remarks and in the end, after exposing the murderer, Chan remarks "Perhaps listening to a 'Chinaman' is no disgrace."[93]

Chinese-born academic and author Yunte Huang acknowledges that "Asian American criticism of the Charlie Chan character . . . carries the weight of the Asian experience in contemporary America," but sees Chan as an "American folk hero" and an example of "a peculiar brand of trickster prevalent in ethnic literature," one of several such characters "indeed rooted in the toxic soil of racism, but racism has made their tongues only sharper, their art more lethally potent . . . As much as well meaning Asian Americans try to banish the character," he writes, Charlie Chan "is here to stay."[94]

Stereotypes in American film and TV shows

[edit]In 2019, 7% of all female characters and 6% of all male characters in the top 100 grossing movies in the United States were Asian.[95] Additionally, a study conducted by AAPIsOnTV (Asian American and Pacific Islanders) indicated that 64% of shows lack a presence of main Asian actors.[96] On the other hand, 96% of shows have a presence of White main actors.[96]

While there has been progress in the representation of Asian actors in TV shows and films through Crazy Rich Asians and Fresh Off The Boat, the portrayal of stereotypes is still a present issue.[97] Asian actors are cast for movies usually represent stereotypes of East Asians. In most instances, they also play the roles of sex workers, nerds, foreigners, and doctors.[98] In the episode "A Benihana Christmas" of The Office, Michael Scott (as Steve Carell) has to mark Nikki (played by Kulap Vilaysack) with a Sharpie, because he is unable to differentiate her from Amy (played by Kathrien Ahn).[99] The portrayal of Asian Americans is based on the stereotype that they look identical.[99] In Mean Girls, Trag Pak (played by Ky Pham) and Sun Jin Dinh (played by Danielle Nguyen), are depicted as overly sexual students who have an affair with the PE teacher and possess limited English skills.[100] The Big Bang Theory portrays Rajesh Koothrapalli (played by Kunal Nayyar) as someone who is unable to form romantic relationships and communicate with women.[101]

A study of top grossing films in the 2010s found that films encouraged audiences to laugh at 43.4% of Asian and Pacific Islander characters, meaning that they may be serving as a "punchline".[102]: 33

According to Christina Chong, if Asian actors in American movies are needed, it is usually for "international regional accuracy".[103] These inaccurate representations shape public perceptions due to the large influence TV shows and films have on the understanding of people from different backgrounds.[97]

Men

[edit]Emasculation and celibacy

[edit]In the mid-1800s, early Chinese immigrant workers were derided as emasculated men due to cultural practices of Qing dynasty. The Chinese workers sported long braids (the "queue hairstyle" which was compulsory in China) and sometimes wore long silk gowns.[104] Because Chinese men were seen as an economic threat to the white workforce, laws were passed that barred the Chinese from many "male" labor-intensive industries, and the only jobs available to the Chinese at the time were jobs that whites deemed "women's work" (i.e., laundry, cooking, and childcare).[104]

In the 2006 documentary The Slanted Screen, Filipino American director Gene Cajayon talks about the revised ending for the 2000 action movie Romeo Must Die, a retelling of Romeo and Juliet in which Aaliyah plays Juliet to Jet Li's Romeo. The original ending had Aaliyah kissing Chinese actor Li, which would have explained the title of Romeo, a scenario that did not test well with an urban audience.[105] The studio changed the ending to Trish (Aaliyah) giving Han (Li) a tight hug. According to Cajayon, "Mainstream America, for the most part, gets uncomfortable with seeing an East Asian man portrayed in a sexual light."[105]

One study has shown East Asians as being perceived as being "less masculine" than their white and black American counterparts.[5] East Asian men are also emasculated, being stereotyped and portrayed as having small penises.[106] Such an idea fueled the phenomenon that being a bottom in a homosexual relationship for East Asian men is more of a reflection of what is expected of them, than a desire.[107] These stereotypes are attempts of an overall perception that East Asian men are less sexually desirable to women compared to men of other races, especially whites.[108] These stereotypes may have an impact on the dating lives of Asian men; a 2018 study found that Asian teenaged males were less likely than their non-Asian peers to have a romantic relationship.[109]

When Bruce Lee established a presence in Hollywood, he was one of the few Asians who had achieved "alpha male" status on screen in the 20th century.[110]

Study findings from an analysis of the TV show Lost suggest that portrayals of East Asian males have not significantly changed.[111] According to Elizabeth Tunstall, East Asian men in the West are still largely denied the stereotypical masculinity ideal of Western societies; however, the hybrid "soft masculinity" of K-pop has improved the image of Asian men as potentially desirable partners among K-pop fans in Western countries.[112]

Predators of white women

[edit]

East Asian men have been portrayed as threats to white women by white men in many aspects of American media.[113] Depictions of East Asian men as "lascivious and predatory" were common at the turn of the 20th century.[114] Fears of "white slavery" were promulgated in both dime store novels and melodramatic films.

Between 1850 and 1940, both US popular media and propaganda before and during World War II humanized Chinese men, while portraying Japanese men as a military and security threat to the country, and therefore a sexual danger to white women[4] due to the perception of a woman's body traditionally symbolizing her "tribe's" house or country.[115] In the 1916 film Patria, a group of fanatical Japanese individuals invade the United States in an attempt to rape a white woman.[116] Patria was an independent film serial funded by William Randolph Hearst in the lead up to the United States' entry into World War I.

The Bitter Tea of General Yen portrays the way in which an "Oriental" beguiles white women. The film portrays Megan Davis (Barbara Stanwyck) coming to China to marry a missionary (Gavin Gordon) and help in his work. They become separated at a railway station, and Davis is rescued/kidnapped by warlord General Yen (Nils Asther). Yen becomes infatuated with Davis, and knowing that she is believed to be dead, keeps her at his summer palace. That being said, it was also one of the first films to deal openly with interracial sexual attraction (despite the fact that the actor playing General Yen is played by a non-Asian actor).

Misogynists

[edit]Another stereotype of East Asian men, especially of Chinese men, is that they are misogynistic, insensitive, and disrespectful towards women. However, studies have shown that East Asian American men express more gender egalitarian attitudes than the American average.[117] East Asian men are commonly portrayed in Western media as male chauvinists.[118]

Even literature written by Asian American authors is not free of the pervasive popular cliche of Asian men. Amy Tan's book The Joy Luck Club has been criticized by Asian American figures such as Frank Chin for perpetuating racist stereotypes of Asian men.[119][120]

Women

[edit]Dragon Lady

[edit]In the 19th and 20th centuries, Western film and Western literature sometimes stereotyped powerful Asian women as "Dragon Ladies" and subservient Asian women as "Lotus Blossoms". These memes persists in to the present time, and other stereotypes related to the Lotus Blossom include the hyper-feminine "China dolls", "Geisha girls" and war brides.[6][7]

More recently, the Dragon Lady stereotype was embodied by Ling Woo, a fictional character in the US comedy-drama Ally McBeal (1997–2002), whom the American actress Lucy Liu portrayed. Ling is a cold and ferocious[121] bilingual Chinese American lawyer, who is fluent in both English and Mandarin[122] and is well-versed in the arts of sexual pleasuring unknown to the American world.[122][123] At the time, she provided the only major representation of East Asian women on television,[123] apart from news anchors and reporters.[124] Because there were no other major Asian American celebrity women whose television presence could counteract the Dragon Lady stereotype,[123] the portrayal of Ling Woo attracted much scholarly attention.[124]

This attention has led to the idea that orientalist stereotyping is a specific form of racial microaggression against women of East Asian descent. For example, while the beauty of Asian American women has been exoticized, Asian American women have been stereotyped as submissive in the process of sexual objectification.[47] University of Wyoming Darrell Hamamoto, Professor of Asian American Studies at the University of California, Davis, describes Ling as "a neo-Orientalist masturbatory fantasy figure concocted by a white man whose job it is to satisfy the blocked needs of other white men who seek temporary escape from their banal and deadening lives by indulging themselves in a bit of visual cunnilingus while relaxing on the sofa." Hamamoto does maintain, however, that Ling "sends a powerful message to white America that East Asian American women are not to be trifled with. She runs circles around that tower of Jell-O who serves as her white boyfriend. She's competitive in a profession that thrives on verbal aggression and analytical skill."[125] Contemporary actress Lucy Liu has been accused of popularizing this stereotype by characters she has played in mainstream media.[126]

Hypersexuality and submissiveness

[edit]An iconic source of images of East Asian women in the 20th century in the West is the 1957 novel The World of Suzie Wong that was adapted into a movie in 1960, about a Hong Kong woman.[127][128][129][130] The titular character is represented through a frame of white masculine heterosexual desire: Suzie is portrayed as a submissive prostitute that is sexually aroused at the idea of being beaten by a white man. UC Berkeley Professor of Asian American Studies Elaine Kim argued in the 1980s that the stereotype of East Asian women as submissive has impeded their economic mobility.[131]

According to author Sheridan Prasso, the "China [porcelain] doll" stereotype and its variations of feminine submissiveness recurs in American movies. These variations can be presented as an associational sequence such as: "Geisha Girl/Lotus Flower/Servant/China Doll: Submissive, docile, obedient, reverential; the Vixen/Sex Nymph: Sexy, coquettish, manipulative; tendency toward disloyalty or opportunism; the Prostitute/Victim of Sex Trade/War/Oppression: Helpless, in need of assistance or rescue; good-natured at heart."[104]

Another is Madama Butterfly (Madame Butterfly), an opera by Giacomo Puccini, Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. It is the story of a Japanese maiden (Cio-Cio San), who falls in love with and marries a white American navy lieutenant. After the officer leaves her to continue his naval service away from Japan, Cio-Cio San gives birth to their child. Cio-Cio San blissfully awaits the lieutenant's return, unaware that he had not considered himself bound by his Japanese marriage to a Japanese woman. When he arrives back in Japan with an American wife in tow and discovers that he has a child by Cio-Cio San, he proposes to take the child to be raised in America by himself and his American wife. The heartbroken Japanese girl bids farewell to her callous lover, then kills herself.

There has been much controversy about the opera, especially its treatment of sex and race.[132][133][134] It is the most-performed opera in the United States, where it ranks Number 1 in Opera America's list of the 20 most-performed operas in North America.[135] This popularity only helps to perpetuate the stereotype of Japanese women being self-sacrificing victims to "cruel and powerful" Western men.[136]

Butterfly received a modern adaptation in the form of Miss Saigon, a 1989 musical by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil. This musical has also been criticized for what some have perceived as racist or sexist overtones. Criticism has led to protests against the musical's portrayal of Asian men, Asian women, and women in general.[137] It banked a record $25 million in advance ticket sales when it was opening on Broadway.[138]

According to artist and writer Jessica Hagedorn in Asian Women in Film: No Joy, No Luck, Asian women in golden era Hollywood film were represented as sexually passive and compliant. According to Hagedorn, "good" Asian women are portrayed as being "childlike, submissive, silent, and eager for sex".[139]

In instances of rape in pornography, a study found that young East Asian women are overrepresented.[140] It had been suggested that the hypersexualized yet compliant representations of East Asian women being a frequent theme in American media is the cause of this.[141] In addition, East Asian women being often stereotyped as having tighter vaginas than other races is another suggested factor.[140]

Tiger mother

[edit]In early 2011, the Chinese-American lawyer and writer Amy Chua generated controversy with her book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, published in January 2011. The book was a memoir about her parenting journey using strict Confucian child rearing techniques, which she describes as being typical for Chinese immigrant parents.[142] Her book received a huge backlash and media attention and ignited global debate about different parenting techniques and cultural attitudes that foster such techniques.[143] Furthermore, the book provoked uproar after the release where Chua received death threats, racial slurs, and calls for her arrest on child-abuse charges.[144]

The archetypal Chinese tiger mom is (similar to the Jewish mother stereotype and the Japanese Kyoiku mama) refers to a strict or demanding mother who pushes her children to high levels of scholastic and academic achievement, using methods regarded as typical of childrearing in East Asia to the detriment of the child's social, physical, psychological and emotional well-being. According to Marie Moro, Amy Chua links the academic success of Chinese Americans to Tiger mothering.[8] Paul Tullis suggests that this assumption is unfounded, and cites a study suggesting that children of purported "tiger parents" actually have slightly worse GPAs than those raised by non-tiger parents.[9]

Asian baby girl

[edit]"Asian baby girl", commonly abbreviated "ABG" and sometimes referred to as "Asian bad girl" or "Asian baby gangster", is a term that arose in the 1990s New York City area, originally used to describe Chinese American women involved in gangster subcultures. These women were a part of, or admired the lifestyles of the New York Chinatown gangs, before the crime crackdowns ordered by Mayor Rudy Giuliani caused many of them to become defunct.[145] The term was then adopted by other Asian Americans from outside the Chinese American gangster subculture of the East Coast. The looks, fashion, and aesthetics associated with ABGs gained popularity in the 2010s, and was regarded as a negative stereotype similar to the "valley girl" or "dumb blond" stereotype.[145] It appeared in online forums such as the Subtle Asian Traits Facebook group.[146] In the 2020s, the ABG stereotype was adopted as a fashion trend on social media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram. It refers primarily to millennial or younger women who are highly outgoing and have adopted a gangster aesthetic or personality without necessarily being involved with actual organized crime. Other associated traits include an interest in partying and fashion and sexual activeness.[147][148]

Physical attributes and traits

[edit]Darrell Y. Hamamoto, an American Orientialist and professor of Asian American studies at UC Irvine argued that a pervasive racialized discourse exists throughout American society, especially as it is reproduced by network television and cinema.[149] Critics argue that portrayals of East Asians in American media fixating on the epicanthic fold of the eyelid have the negative effect of caricature, whether describing the Asiatic eye positively as "almond-shaped" or negatively as "slanted", "slant-eyed", or "slanty". These "slanted" stereotypes have even led to the spread of a sexual rumor purporting that Asian women possess sideways vaginas.[150] Even worse, these critics contend, is the common portrayal of the East Asian population as having yellow, sometimes orange or even lemon colored skin tones (which the critics reference as colorism).

This colorist portrayal negatively contrasts "colored" Asian Americans with the European population of North America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. East Asians are also stereotyped (or orientalized) as having straight dark (or shiny "blue") hair usually styled in a "bowl cut" (boys) or with straight overgrown bangs (girls). They are often homogenized as one indiscriminate monolithic conglomeration of cultures, languages, histories, and physiological and behavioral characteristics. Almost invariably it is assumed that a person of Asian descent has ancestral origins from an East Asian country.[151][152]

There is also a common assumption that people of East Asian descent are always Chinese or are supposed to be proficient in a Chinese language. This often results in racist remarks and ethnic slurs against Asian Americans such as telling them to "Go back to China" even if the Asian-American person does not happen to be of Chinese descent. In reality, the term "Asian American" broadly refers to all people who descend from the Continental Asian sub-regions of Central, East, Southeast, South, and West Asia as a whole. While people of Chinese descent make up roughly 5 million of the roughly 18 million Asians in America, a plurality, other Asian American ethnic groups such as the Filipinos, Indonesian, Japanese, Koreans and Vietnamese make up a larger portion of the total.[153]

East Asians are often stereotyped as being inherently bad drivers.[154] East Asians are also stereotyped as academic overachievers who are intelligent but socially inept, either lacking social skills or being asocial.[155] A 2010 study found that East Asians in the United States are most likely to be perceived as nerds. This stereotype is socially damaging and contributes to a long history of Asian exclusion in USA.[156]

East Asians have been stereotyped as immature, childlike, small, infantile looking, needing guidance and not to be taken seriously.[157][158][159][160] The infantilized stereotype is on both physical and mental aspects of the race. East Asians are believed to mature slower in appearance and body, while also thought of as less autonomous and therefore requiring guidance from the "mature" white race.[157][158] Like children, the perception is that they have little power, access, and control over themselves. The stereotype goes hand in hand with fetish against Asian women, who are perceived as more demure, submissive, more eager to please and easily yielding to powerful men.[159][160][161]

A psychological experiment conducted by two researchers found that East Asians who do not conform to common stereotypes and who possess qualities such as dominance in the workplace are often seen as "unwelcome and unwanted by their co-workers" and can even elicit negative reactions and harassment from their fellow employees of other racial backgrounds.[162]

Physicality and sports

[edit]East Asian bodies are often stereotyped of as lacking the innate athletic ability to endure labor-intensive tasks which is required to play and excel in sports, especially in sporting disciplines that involve heavy amounts of physical contact.[163] This stereotype has led to discrimination in the recruitment process for professional American sports teams where Asian American athletes are highly underrepresented.[164][165][166][167][168]

The Taiwanese-American professional basketball player Jeremy Lin believed that his race played a role in him going undrafted in NBA initially.[169] This belief has been echoed and reiterated by sports writer Sean Gregory of Time and NBA commissioner David Stern.[170] Although Asian Americans comprised 6% of the nation's population in 2012, Asian American athletes represented only 2% of the NFL, 1.9% of the MLB and less than 1% in both the NHL and NBA.[171]

Stereotypes of Asian students

[edit]In Western universities, students from East Asia and Asian American students often face unfair treatment and stereotypes. People sometimes think Asian American students don't have any problems because they're seen as the "model minority," meaning they're expected to do well in school without struggle. This stereotype can prevent others from comprehending or acknowledging the real challenges some face, like feeling left out, stressed, or not getting enough help. On the other hand, East Asian students are also sometimes imagined as not having good thinking skills, copying others' work, and not helping the class environment. This is conflicts with the model minority stereotype.[172]

Deference to authority

[edit]When Asian American scholars try to work with their teachers or find a mentor, they sometimes run into misunderstandings because their cultural background is different. For example, in many Asian cultures, it's important to respect those who are older or in charge, and people often talk in ways that are polite and not too direct. But in American culture, people are usually very straight to the point and treat everyone the same, no matter their age or position. This can make communication tricky between Asian American students and their mentors who might expect them to speak up more or brag about their achievements, which can feel uncomfortable or rude to them.[173]

Impact on earning

[edit]In the context of East Asians in North America, it has been found that they are stereotypically viewed as more competent but less warm and less dominant compared to Whites. However, the prescriptive aspect of these stereotypes, particularly the belief that East Asians should be less dominant, has notable implications in the workplace.[174]

In the research conducted by Sanae Tashiro and Cecilia A. Conrad delves into the widely held perception that Asian-Americans, known for their proficiency in mathematics and technology, might enjoy higher earnings, especially in positions that necessitate computer skills.[175] The study scrutinizes whether this favorable reputation indeed correlates with increased wages for Asian-Americans in comparison to other racial groups. Utilizing data from the expansive Current Population Survey, Tashiro and Conrad aim to uncover whether Asian-Americans genuinely receive a financial premium for employing computer skills in their professional roles.

Contrary to common assumptions, their findings reveal that simply being Asian-American does not assure a wage boost for computer-centric tasks. Their investigation further addresses how stereotypes could potentially influence wage structures. The premise explored is whether employers are inclined to offer higher wages to individuals from groups perceived positively. However, Tashiro and Conrad's research findings contradict this assumption, demonstrating that such positive stereotypes do not afford Asian-Americans any wage advantage in technology-oriented employment.[175]

Health

[edit]Stella S. Yi, and Simona C. Kwon have examined the significant impact of poor data quality and prevalent stereotypes on the health of Asian Americans. The discussion delves into how Asian American health is significantly influenced by two primary factors: the inadequate quality of their health data and prevailing stereotypes.[176] It unfolds the narrative that the complex health scenarios of Asian Americans stem from the nation's history, migration patterns, and specific policies affecting this group. A critical issue highlighted is the aggregation of diverse Asian communities, such as Chinese, Vietnamese, and Bangladeshi, into a single category, obscuring the distinct health challenges each group faces. Furthermore, the persistence of stereotypes paints a misleading picture of Asian Americans as not facing health disparities, which is inaccurate.

Three stereotypes are notably discussed: the "model minority" myth, suggesting Asian Americans are universally successful and self-sufficient; the "healthy immigrant" effect, falsely indicating that all Asian immigrants are healthier than U.S.-born individuals; and the "perpetual foreigner" stereotype, which unjustly views Asian Americans as eternal outsiders in the U.S.[176] The findings reveal that these stereotypes, combined with the lack of detailed data, lead to Asian Americans often being overlooked in health resources and attention, which perpetuates stereotypes due to insufficient data to challenge them. This data shortage is, in part, a result of these stereotypes.

See also

[edit]- Anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States

- Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States

- Anti-Korean sentiment

- Anti-Mongolianism

- Chinese Exclusion Act

- Ching chong

- Covert racism

- Elderly martial arts master, a stock character

- Fresh off the boat

- Gook

- Microaggression

- Oriental riff

- Racism in the United States

- Stereotypes of groups within the United States

- Xenophobia and racism related to the COVID-19 pandemic

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Kashiwabara, Amy, Vanishing Son: The Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation of the Asian-US Man in US Mainstream Media, UC Berkeley Media Resources Center

- ^ a b Felicia R. Lee, "'Model Minority' Label Taxes Asian Youths," New York Times, March 20, 1990, pages B1 & B4.

- ^ a b Matthew Yi; et al. (April 27, 2001). "Asian Americans seen negatively". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h William F. Wu, The Yellow Peril: Chinese Americans in American Fiction, 1850–1940, Archon Press, 1982.

- ^ a b "Racial Stereotypes and Interracial Attraction: Phenotypic Prototypicality and Perceived Attractiveness of Asians" (PDF). Washington.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2018. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

Cultural studies literature has suggested that stereotypes of Asians portray both genders as being feminine. According to Fujino (1992) and Williams (1994), Asian women are portrayed in the media as "exotic, subservient, or simply nice" (Mok, 1999, p.107) – all feminine traits. Asian men, in contrast, are presented as lacking in the physical appearance and social skills needed to attract women (Mok, 1999, p. 107).

- ^ a b Tajima, Renee (1985). Lotus Blossoms Don't Bleed: Images of Asian Women in Making Waves: An Anthology of Writing By And About Asian American Women (PDF) (1 ed.). Beacon Press. pp. 308–309. ISBN 9780807059050.

- ^ a b Ukockis, Gail (May 13, 2016). Women's Issues for a New Generation: A Social Work Perspective. Oxford University Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-19-023941-1.

Media portrayals of Asian Americans continue to present these memes: Dragon Lady, Lotus Blossom and the male as a sexless nerd. The Dragon Lady has too much power, whereas the Lotus Blossom and the male loser have too little power (Ono & Pham, 2009).

- ^ a b Moro, Marie Rose; Welsh, Geneviève (March 7, 2022). Parenthood and Immigration in Psychoanalysis: Shaping the Therapeutic Setting. Routledge. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-000-54479-4.

"...Amy Chua's book, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother (Chua, 2011), depicts a strict, rigid form of Chinese mothering, in contrast to permissive Western parenting, as essential to the academic and professional success of Chinese Americans (Cheah et al., 2013; Guo, 2013).

- ^ a b Tullis, Paul (May 8, 2013). "Poor Little Tiger Cub". Slate.

- ^ "Conference Indorses Chinese Exclusion; Editor Poon Chu Says China Will... – Article Preview – The". New York Times. December 9, 1905. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ "History World: Asian Americans". Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- ^ Neumann, Klaus; Tavan, Gwenda, eds. (February 12, 2002). Office of Ethnic Affairs – Formal Apology To Chinese Community. Archives of Australian National University. doi:10.22459/DHM.09.2009. ISBN 9781921536953. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Chinese Immigration Act 1885, c". Asian.ca. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ Frank H. Wu. "Asian Americans and the Perpetual Foreigner Syndrome". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- ^ Lien, Pei-te; Mary Margaret Conway; Janelle Wong (2004). The politics of Asian Americans: diversity and community. Psychology Press. p. 7. ISBN 9780415934657. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

In addition, because of their perceived racial difference, rapid and continuous immigration from Asia, and on going detente with communist regimes in Asia, Asian Americans are construed as "perpetual foreigners" who cannot or will not adapt to the language, customs, religions, and politics of the American mainstream.

- ^ Wu, Frank H. (2003). Yellow: race in America beyond black and white. Basic Books. p. 79. ISBN 9780465006403. Retrieved February 9, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Neil Gotanda, "Exclusion and Inclusion: Immigration and American orientalism".

- ^ Johnson, Kevin (1997), Racial Hierarchy, Asian Americans and Latinos as Foreigners, and Social Change: Is Law the Way to Go, Oregon Law Rev., 76, pages 347–356

- ^ a b "Loss of AsianWeek Increases Hole in Asian-American Coverage – NAM". News.ncmonline.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ Weiler, A.H. (October 6, 1961). "The Screen: Breakfast at Tiffany's: Audrey Hepburn Stars in Music Hall Comedy". New York Times. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ Koch, John (April 1, 1990). "Quick Cuts and Stereotypes". The Boston Globe. Boston. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ Yang, Jeff (July 17, 2011). "'Breakfast at Tiffany's' protest is misguided: Let's deal openly with the film's Asian stereotypes". NY Daily News. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- ^ Kerr, David. "Stereotypes in the Media". mrkerronline. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Stacy; Choueiti, Marc; Pieper, Katherine; Gillig, Traci; Lee, Carmen; DeLuca, Dylan (2015). Inequality in 700 Popular Films: Examining Portrayals of Gender, Race & LGBT Status from 2007 to 2014. The Harnish Foundation. pp. 1–31.

- ^ Zheng, Robin (2016). "Why Yellow Fever Isn't Flattering: A Case against Racial Fetishes" (PDF). Journal of the American Philosophical Association. 2 (3): 406. doi:10.1017/apa.2016.25.

- ^ King, Ritchie (November 20, 2013). "The uncomfortable racial preferences revealed by online dating". Quartz. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "APA PsycNet". APA PsycNet. June 1, 1999. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ Ren, Yuan (July 2014). "'Yellow fever' fetish: Why do so many white men want to date a Chinese woman?".

- ^ Chou, Rosalind S. (January 5, 2015). Asian American Sexual Politics: The Construction of Race, Gender, and Sexuality. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 65. ISBN 9781442209251.

- ^ Woan, Sunny (March 2008). "White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence". Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice. 14 (2): 2, 19. ISSN 1535-0843.

- ^ a b Thomas, Sabrina (December 2021). Scars of War: The Politics of Paternity and Responsibility for the Amerasians of Vietnam. U of Nebraska Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4962-2935-9.

- ^ Moore, John H. (2008). Encyclopedia of Race and Racism. Macmillan Reference USA/Thomson Gale. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-02-866021-9.

- ^ Nagatomo, Diane Hawley (April 7, 2016). Identity, Gender and Teaching English in Japan. Multilingual Matters. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-78309-522-3.

- ^ "Eddie Huang on racial insensitivities behind MSG, Chinese food criticisms". NBC News. January 14, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "China Food Scare: A Dash of Racism". ABC News. February 11, 2009. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Dai, Serena (March 23, 2016). "Please Stop Writing Racist Restaurant Reviews". Eater NY.

- ^ Bahk, Jean Rachel (April 30, 2021). "The History of the Dog-Eating Stereotype". Inlandia. Retrieved September 14, 2024.

- ^ Wu, Nicholas. "GOP senator says China 'to blame' for coronavirus spread because of 'culture where people eat bats and snakes and dogs'". USA TODAY.

- ^ Gee, Gilbert C.; Ro, Marguerite J.; Rimoin, Anne W. (July 1, 2020). "Seven Reasons to Care About Racism and COVID-19 and Seven Things to Do to Stop It". American Journal of Public Health. 110 (7): 954–955. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305712. PMC 7287554.

- ^ "Model Minority Stereotype". cmhc.utexas.edu. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ^ Lu, Jackson; Nisbett, Richard; Morris, Michael (March 3, 2020). "Why East Asians but not South Asians are underrepresented in leadership positions in the United States". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (9): 4590–4600. Bibcode:2020PNAS..117.4590L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1918896117. PMC 7060666. PMID 32071227.

- ^ a b Chung, Eric; Dong, Samuel; Hu, Xiaonan; Kwon, Christine; Liu, Goodwin. "A Portrait of Asian Americans in the Law". Center of the legal profession Harvard law School. Harvard Law School. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ Acosta, David; Poll-Hunter, Norma Iris; Eliason, Jennifer (November 2017). "Trends in Racial and Ethnic Minority Applicants and Matriculants to U.S. Medical Schools, 1980–2016". Analysis in Brief. 17. Association of American Medical Colleges. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ "The Model Minority Myth". Center of the legal profession Harvard law School. Harvard Law School.

- ^ Gee, Buck; Peck, Denise (2015). "The Illusion of Asian Success". Ascend.

- ^ Asian-American Scientists: Silent No Longer: 'Model Minority' Mobilizes – Lawler 290 (5494): 1072 – Science.

- ^ a b c "Racial Microaggressions and the Asian American Experience" (PDF).

- ^ Stacey J. Lee, Unraveling the "Model Minority" Stereotypes: Listening to Asian American Youth, Teachers College Press, New York: 1996 ISBN 978-0-8077-3509-1.

- ^ Bill Sing, "'Model Minority' Resentments Spawn Anti-Asian-American Insults and Violence," Los Angeles Times February 13, 1989, p. 12.

- ^ Greg Toppo, "'Model' Asian student called a myth ; Middle-class status may be a better gauge of classroom success," USA Today, December 10, 2002, p. 11.

- ^ Benjamin Pimentel, "Model minority image is a hurdle, Asian Americans feel left out of mainstream," San Francisco Chronicle, August 5, 2001, p. 25.

- ^ "What 'Model Minority' Doesn't Tell," Chicago Tribune, January 3, 1998, p. 18.

- ^ Nguyen Do, Kevin (December 2020). "Positive Portrayal versus Positive Stereotype: The Effect of Media Exposure to the Model Minority Stereotype on Asian Americans' Self-Concept and Emotions". Thesis for University of California. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "Model Minority". Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Kim, Angela; Yeh, Christine J (2002). "Stereotypes of Asian American Students". ERIC Digest. ERIC Educational Reports. ISSN 0889-8049.

- ^ Yang, KaYing (2004). "Southeast Asian American Children: Not the Model Minority". The Future of Children. 14 (2): 127–133. doi:10.2307/1602799. JSTOR 1602799. S2CID 70895306.

- ^ a b Ronald Takaki (June 16, 1990). "The Harmful Myth of Asian Superiority". The New York Times. p. 21.

- ^ Woo, Deborah (July 1, 1994). "The Glass Ceiling and Asian Americans". Cornell University ILR School.

- ^ "The Glass Ceiling for African, Hispanic (Latino), and Asian Americans," Ethnic Majority, The Glass Ceiling for African, Hispanic, and Asian Americans Archived September 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Constable, Pamela, "A 'Glass Ceiling' of Misperceptions," WashingtonPost, October 10, 1995, Page A01 Washingtonpost.com: A GLASS CEILING' OF MISPERCEPTIONS.

- ^ Chen, Edith Wen-Chu; Grace J. Yoo (December 23, 2009). Encyclopedia of Asian American Issues Today, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-313-34749-8.

- ^ Ancheta, Angelo N. (2006). Race, Rights, and the Asian American Experience. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-3902-1.

- ^ Chou, Rosalind; Feagin, Joe (November 5, 2008). Myth of the Model Minority (1st ed.). Routledge.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, Srilata: From "Yellow Peril" to "Model Minority": The Transition of Asian Americans: Additional information about the document that does not fit in any of the other fields; not used after 2004. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Mid-South Educational Research Association (30th, Little Rock, AR, November 14–16, 2001): Full text available.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, Srilata (October 31, 2001). ERIC PDF Download. Eric.ed.gov. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ Aronson J.; Lustina M. J.; Good C.; Keough K.; Steele C. M.; Brown J.; When white men can't do math: Necessary and sufficient factors in stereotype threat, Journal of experimental social psychology vol. 35, no1, pp. 29–46 (1 p.3/4): Elsevier, San Diego 1999.

- ^ "Mental Health and Depression in Asian Americans" (PDF). National Asian Women's Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2006 – via University of Hawaii.

- ^ a b Elizabeth Cohen (May 16, 2007). "Push to achieve tied to suicide in Asian-American women". CNN.

- ^ Flowers, Ronald B. (1990). Minorities and criminality. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 190.

- ^ "Section IV: Persons Arrested". Crime in the United States (PDF) (Report). FBI. 2003. pp. 267–336. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 27, 2004.

- ^ Walter E. Williams (March 9, 2003). "Affirmative Action Bake Sale". George Mason University.

- ^ Johnson, Brian D.; Betsinger, Sara (November 9, 2009). "Punishing the "Model Minority": Asian-American Criminal Sentencing Outcomes in Federal District Courts". Criminology. 47 (4): 1045. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00169.x.

- ^ "Our big cultural heritage, our awful little secrets" Archived August 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Some Korean Americans fearful of racial backlash" Archived January 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Sadly, Cho is Most Newsworthy APA of 2007 Archived January 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine." Asianweek. Another incident Binghamton, NY a shooting spree was committed by a naturalized citizen, when Jiverly Wang gunned down 14 people, and injured 3 at the local American Civic Association.January 1, 2008. Retrieved on December 21, 2009.

- ^ Kim, Nami; Joh, Wonhee Anne (December 15, 2019). Feminist Praxis against U.S. Militarism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4985-7922-3.

When New York Police Department officer Peter Liang was convicted and found guilty in 2016 of the shooting death of Akai Kareem Gurley in 2014. questions arose as to whether Officer Liang was a racialized scapegoat punished for simply "doing what he had to do," or a model minority privileged by "adjacent whiteness" whose actions betrayed a fundamental disregard for human life.

- ^ Fang, Jenn (February 23, 2016). "A system that doesn't value black lives can never truly value Asian American lives". Quartz.

- ^ Yellow Face: The documentary part 4 – Asian Americans do face racism, July 5, 2010, archived from the original on December 21, 2021, retrieved February 24, 2013

- ^ Asians, Blacks, Stereotypes and the Media, July 5, 2010, archived from the original on December 21, 2021, retrieved February 24, 2013

- ^ a b Kim, Claire Jean (1999). "The Racial Triangulation of Asian Americans". Politics & Society. 27 (1): 105–138. doi:10.1177/0032329299027001005.

- ^ RHEE, kate-hers (September 24, 2018). "The Black, Asian and White Racial Triangulation".

- ^ Kim 1999, p. 122.

- ^ Sax Rohmer, The Insidious Doctor Fu-Manchu (1913; reprint ed., New York: Pyramid, 1961), p. 17.

- ^ Rohmer, Sax, The Hand of Fu-Manchu (1917; reprint ed., New York: Pyramid, 1962), p. 111.

- ^ Yen Le Espiritu Asian American Panethnicity: Bridging Institutions and Identity Temple University Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0-87722-955-1, 222 pages.

- ^ "Internet Movie Database — list of Charlie Chan movies". IMDB. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Umeda, Mihori. Asian Stereotypes in American Films (Thesis). Chukyo University. p. 145.

- ^ a b Earl Derr Biggers, The House Without a Key (New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1925), p. 76.

- ^ Kim (1982), 179.

- ^ Frank Chin and Jeffery Chan, quoted in Kim (1982), 179.

- ^ Chin and Chan, quoted in Kim (1982), 179.

- ^ Biggers, Earl Derr, Charlie Chan Carries On (1930; reprint ed., New York: Bantam, 1975), p. 233.

- ^ The Chinese Parrot, quoted in Chan (2007).

- ^ Huang, Yunte; Charlie Chan: The Untold Story of the Honorable Detective and His Rendezvous with American History, pp. 282-287; W. W. Norton & Company, 15 August 2011 ISBN 978-0-87722-955-1.

- ^ Stoll, Julia. "Distribution of male and female characters in top grossing films in the United States in 2019, by ethnicity". www.statista.com. Statista. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Chin, Christina; Deo, Meera; DuCros, Faustina; Jong-Hwa Lee, Jenny; Milman, Noriko; Yuen, Nancy (September 2017). Tokens on the Small Screen: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Prime Time and Streaming Television (PDF) (Report). pp. 2–13.

- ^ a b Ramos, Dino-Ray (September 12, 2017). "Asian Americans on TV: Study finds continued Underrepresentation despite new wave of AAPI-led shows". Deadline. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Levin, Sam (April 11, 2017). "'We're the geeks, the prostitutes': Asian American actors on Hollywood's barriers". The guardian. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Murphy, Chris (March 26, 2021). "The Office Actor Kat Ahn calls out show for portrayal of Asian women". Vanity Fair.

- ^ Jokic, Natasha (March 19, 2021). "What Are Some Problematic And Racist Depictions Of East Asian People In TV And Movies That You've Seen?". Buzzfeed. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ Sreedhar, Anjana (September 20, 2013). "5 Most Offensive Asian Characters in TV History". Mic. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media; Coalition of Asian Pacifics in Entertainment; Gold House (2023). I Am Not a Fetish or Model Minority: Redefining What it Means to Be API in the Entertainment Industry (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 5, 2023.

- ^ Chong, Christina Shu Jien. "Where Are the Asians in Hollywood? Can §1981, Title VII, Colorblind Pitches, and Understanding Biases Break the Bamboo Ceiling?" (PDF). Asian Pacific American Law Journal: 29. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c Sheridan Prasso, The Asian Mystique: dragon ladies, geisha girls, & our fantasies of the exotic orient, PublicAffairs, 2005.

- ^ a b Jose Antonio Vargas (May 25, 2007). "Asian Men: Slanted Screen". Washington Post. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ Drummond, Murray JN, and Shaun M. Filiault. "The long and the short of it: Gay men's perceptions of penis size." Gay and lesbian issues and psychology review 3.2 (2007): 121–129.

- ^ Hoppe, Trevor. "Circuits of Power, Circuits of Pleasure: Sexual Scripting in Gay Men's Bottom Narratives.

- ^ Yim, Jennifer Young (2009). Pg. 130, 142 "Being an Asian American Male is Really Hard Actually": Cultural Psychology... University of Michigan. ISBN 9781109120486. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ Kao, Grace; Balistreri, Kelly Stamper; Joyner, Kara (November 2018). "Asian American Men in Romantic Dating Markets". Contexts. 17 (4): 48–53. doi:10.1177/1536504218812869. ISSN 1536-5042.

- ^ Blake, John (August 2, 2016). "Enter the mind of Bruce Lee". cnn.com.

- ^ Biswas, Tulika. Asian Stereotypes lost or found in the first season of TV series Lost? (Thesis). University of Tennessee. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Un-designing masculinities: K-pop and the new global man?". The Conversation. January 23, 2014. Archived from the original on January 27, 2014.

- ^ Espiritu, Y. E. (1997). Ideological Racism and Cultural Resistance: Constructing Our Own Images, Asian American Women and Men, Rowman & Littlefield Publishing.

- ^ Frankenberg, R. (1993). White women, race matters: The social construction of whiteness., University of Minnesota Press.

- ^ Rich, Adrienne. 1994 Blood, Bread and Poetry: Selected Prose 1979–1985. New York: Norton 1986: p. 212.

- ^ Quinsaat, J. (1976). Asians in the media, The shadows in the spotlight. Counterpoint: Perspectives on Asian America (pp 264–269). University of California at Los Angeles, Asian American Studies Center.

- ^ Chua, Peter; Fujino, Diane (1999). "Negotiating New Asian American Masculinities: Attitudes and Gender Expectations". Journal of Men's Studies. 7 (3): 391–413. doi:10.3149/jms.0703.391. S2CID 52220779.

- ^ Conrad Kim. "Big American Misconceptions about Asians". GoldSea.

- ^ Come All Ye Asian American Writers of the Real and the Fake.

- ^ Tanaka Tomoyuki. "Review: The Joy Luck Club" – via Google Groups.

- ^ Shimizu, Celine Parreñas (2007). "The Sexual Bonds of Racial Stardom". The hypersexuality of race. Duke University Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780822340331.

- ^ a b Prasso, Sheridan (2006). "Hollywood, Burbank, and the Resulting Imaginings". The Asian Mystique: Dragon Ladies, Geisha Girls, and Our Fantasies of the Exotic Orient (Illustrated ed.). PublicAffairs. pp. 72–73. ISBN 9781586483944.

- ^ a b c Patton, Tracey Owens (November 2001). ""Ally McBeal" and Her Homies: The Reification of White Stereotypes of the Other". Journal of Black Studies. 32 (2). Sage Publications, Inc.: 229–260. doi:10.1177/002193470103200205. S2CID 144240462.

- ^ a b Dow, Bonnie J. (2006). "Gender and Communication in Mediated Contexts". The SAGE handbook of gender and communication. Julia T. Wood. SAGE. pp. 302–303. ISBN 9781412904230.

- ^ Chisun Lee (November 30, 1999). "The Ling Thing – – News – New York". Village Voice. Archived from the original on April 12, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ Nadra Kareem Nittle. "Five Common Asian-American Stereotypes in TV and Film". About News. Archived from the original on April 12, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ Sumi K. Cho. "Converging Stereotypes in Racialized Sexual Harassment: Where the Model Minority Meets Suzie Wong". In Richard Delgado; Jean Stefancic (eds.). Critical Race Theory: the Cutting Edge. p. 535.

...Hong Kong hooker with a heart of gold.

- ^ Thomas Y. T. Luk. "Hong Kong as City/Imaginary in The World of Suzie Wong, Love is a Many Splendored Thing, and Chinese Box" (PDF). The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 10, 2011.

- ^ "Asian American Cinema: Representations and Stereotypes". Film Reference.

- ^ Staci Ford; Geetanjali Singh Chanda. "Portrayals of Gender and Generation,East and West: Suzie Wong in the Noble House" (PDF). University of Hong Kong. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2009.

- ^ Kim, Elaine (1984). "Asian American writers: A bibliographical review". American Studies International. 22 (2): 41–78.

- ^ "Controversy About the Opera". The New York Times.[dead link]

- ^ "Film Listings". AustinChronicle.com. November 29, 1996. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ "Puccini opera is 'racist': News24: Entertainment: International". News24. February 15, 2007. Archived from the original on September 3, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ "Cornerstones". Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "Puccini's masterpiece transcends its age | The Japan Times Online". Search.japantimes.co.jp. July 3, 2005. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

More insidious perhaps is the opera's enduring fantasy of Japanese women as self-sacrificing and, the helpless victims of cruel and powerful Western men.

- ^ Steinberg, Avi. "Group targets Asian stereotypes in hit musical," Boston Globe, January 2005. Archived April 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2007 – December 15.

- ^ Richard Corliss (August 20, 1990). "Theater: Will Broadway Miss Saigon?". TIME. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved February 21, 2010.

- ^ Hagedorn, Jessica (January–February 1994). "Asian Women in Film: No Joy, No Luck". Ms. Magazine.

- ^ a b Mayall, Alice, and Diana EH Russell. "Racism in pornography." Feminism & Psychology 3.2 (1993): 275–281.

- ^ Park, Hijin. "Interracial Violence, Western Racialized Masculinities, and the Geopolitics of Violence Against Women." Social & Legal Studies 21.4 (2012): 491–509. Web.

- ^ Hodson, Heather (January 15, 2011). "Amy Chua: 'I'm going to take all your stuffed animals and burn them!'". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Emily Rauhala (August 14, 2014) 'Tiger Mother': Are Chinese Moms Really So Different? Time. Retrieved March 8, 2014

- ^ Kira Cochrane (February 7, 2014). "The truth about the Tiger Mother's family". The Guardian. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Tran, Mai (October 7, 2020). "It was a cultural reset: a short history of the ABG aesthetic". i-D Magazine. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ "S.A.D. Defines the "popular" Asian, but it's what we expect.: Networks Course blog for INFO 2040/CS 2850/Econ 2040/SOC 2090".

- ^ Li, Vicki (March 7, 2020). "The Rise of the ABG". The F-Word Magazine. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ Shamsudin, Shazrina (March 5, 2020). "Everything You Need To Know About The Asian Baby Girl Trend That's Taking Over The Internet". Nylon Singapore. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ Darrell Y. Hamamoto, Monitored peril: Asian Americans and the politics of TV representation University of Minnesota Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0-8166-2368-6, 311 pages.

- ^ "After 170 Years, the 'Sideways Asian Vagina' Myth Still Won't Go Away". MEL Magazine. January 16, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ Jung Heum Whang (September 2007). Body Politics of the Asian American Woman: From Orientalist Stereotype to the Hybrid Body. ISBN 9780549173045. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ^ Lisa Lowe (1996). Immigrant Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822318644. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ^ "The Rise of Asian Americans". pewsocialtrends.org. Pew Research Center. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Tewari, Nita; Alvarez, Alvin N. (September 17, 2008). Asian American Psychology:Asians Bad Drivers False. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781841697499. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ "Perceptions of Asian American Students: Stereotypes and Effects". Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ Zhang, Qin (2010). "Asian Americans Beyond the Model Minority Stereotype: The Nerdy and the Left Out". Journal of International and Intercultural Communication. 3 (1): 20–37. doi:10.1080/17513050903428109. S2CID 144533905.

- ^ a b Shibusawa, Naoko (2010). America's Geisha Ally: Reimagining the Japanese Enemy. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674057470.

- ^ a b Petersen-Smith, Khury (January 19, 2018). ""Little Rocket Man": The Anti-Asian Racism of US Empire". Verso Books.

- ^ a b Lim, Audrea (January 6, 2018). "The Alt-Right's Asian Fetish". New York Times.

- ^ a b Hu, Nian (February 4, 2016). "Yellow Fever: The Problem with Fetishizing Asian Women". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ Song, Young In; Moon, Ailee (July 27, 1998). Korean American Women: From Tradition to Modern Feminism. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275959777 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Dominant East Asians face workplace harassment, says study". psychology. University of Toronto, Rotman School of Management. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Azzarito, Laura; Kirk, David (October 10, 2014). Pedagogies, Physical Culture, and VisualMethods. Sports. Routledge. ISBN 9780415815727. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Samer Kalaf. "Asian population critically underrepresented in NFL". Sports. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Michelle Banh. "Hey American Sports! Where are all the Asians at?". Sports. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Bryan Chu (December 16, 2008). "Asian Americans remain rare in men's college basketball". Sports. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "Studying Antecedent and Consequence of Self Efficacy of Asian American Sport Consumers: Development of a Theoretical Framework" (PDF). Socioeconomics. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "The Lack of Asians and Asian-American Athletes in Professional Sports". Sports. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Barron, David (April 5, 2013). "Lin tells "60 Minutes" his ethnicity played a role in him going undrafted". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 8, 2013.

- ^ Gregory, Sean (December 31, 2009). "Harvard's Hoops Star Is Asian. Why's That a Problem?". Time. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2010.