Battle of Pine Creek

| Battle of Pine Creek (Battle of Tohotonimme) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Coeur d'Alene War, Yakima War | |||||||

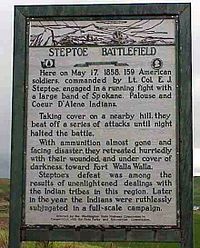

Monument to the Battle of Pine Creek in Rosalia, Washington | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| United States of America | Coeur D' Alenes Yakama, Cayuse, Spokane, possibly Walla Walla Indians, assorted Native American tribes | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Bvt. Lt. Col. Edward Steptoe | Kamiakin, et al. | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 164 riflemen[1] | 800–1,000 (est.) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 19 dead 27+ wounded (est.) | 9 dead (est.); 40+ wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Pine Creek, also known as the Battle of Tohotonimme and the Steptoe Disaster,[2] was a conflict between United States Army forces under Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Edward Steptoe and members of the Coeur d'Alene, Palouse and Spokane Native American tribes.[3] It took place on May 17, 1858, near what is present-day Rosalia, Washington.[4] The Native Americans were victorious.

Prelude

[edit]Tension had been growing on the Columbia Plateau since the 1855 Walla Walla Council forced tribes to cede vast portions of land. Yakama chief Kamiakin opposed the treaties, and so did many leaders of the Nez Perce, Cayuse, and Walla Walla nations. Adding to the tension, miners trespassed on tribal lands and attacked Indians. Some tribes retaliated with isolated killings of whites. In late 1855, the Oregon militia mounted an attack resulting in the Battle of Walla Walla and the murder of Walla Walla chief Peopeomoxmox. Rumors that Lieutenant John Mullan would build a military road across their land fueled the outrage of tribes in the region. Finally, in 1858, Palouse people killed two miners as an act of vengeance for crimes against fellow tribal members. Fearing further violence, whites living at nearby Fort Colvile petitioned Steptoe for military protection.[5]

Steptoe departed Fort Walla Walla on May 6, 1858. His stated mission was to investigate the murder of the two prospectors and to demonstrate a military presence in order to calm the white settlers who were encroaching on Indian lands. Steptoe also wanted to recover a herd of cattle that a group of Palouses had driven from Fort Walla Walla. Leaving the fort, Steptoe's command of 159 soldiers were each issued about 40 rounds of ammunition. The group also ported two mountain howitzers. When Steptoe crossed the Snake River and entered the territory of the Spokane nation, he violated the promise of Governor Isaac Stevens that whites would respect Spokane land as long as the tribe agreed to remain peaceful.[5]

Battle

[edit]On May 15, Steptoe made camp on a hilltop south of Rosalia, Washington, in the territory of the Coeur d'Alenes. The next day, a party of tribal leaders confronted Steptoe and demanded an explanation for his incursion. Steptoe told them that he sought a resolution to tensions between miners and the tribes near Fort Colvile. He asked for help to cross the Spokane River, which was running high with spring snow melt. The tribes refused.

On the morning of May 17, Steptoe decided to turn back. He led his troops near the confluence of Spring Valley Creek and North Pine Creek. It was at this time a group of Coeur d'Alenes, joined by some Palouses, attacked. A running battle ensued for the next ten hours. More warriors joined the battle, and soon Steptoe found himself under attack by more than a thousand Palouse, Spokane, and Coeur d'Alene people. By early afternoon, Steptoe found himself defending against the attackers from a hill overlooking Pine Creek from the east. The Indian warriors withdrew for the night, expecting to finish the battle the next morning. They did not know that Steptoe's forces were down to about three rounds of ammunition per man. Under cover of darkness and a driving rain, Steptoe abandoned his supplies and cannon. He then led his command through enemy lines to safety toward Fort Walla Walla without being detected.[6]

Aftermath

[edit]After the battle, Jesuits from the nearby Sacred Heart Mission traveled to Fort Vancouver in hopes of negotiating a peace agreement. Steptoe's commanding officer, General Newman S. Clarke, demanded the surrender of all warriors who had participated in the battle and the restoration of all property captured. Clarke also demanded that Yakama chief Kamiakin be exiled from the region. Clarke's most onerous demand, however, was that the Coeur d'Alenes allow Mullan to build his military road through their territory.

Tribal leaders rejected Clarke's terms. Some, including Spokane Garry, desired peace but refused to surrender their neighbors. Some other leaders did not want peace at all. In August 1858, Clarke dispatched Colonel George Wright with five hundred soldiers. At the Battle of Four Lakes, Wright defeated a force of approximately five hundred warriors from the allied tribes. Three days later, Wright won another victory at the Battle of Spokane Plains. Their resistance crushed, the tribes were forced to sign new treaties and move to reservations. Within the decade, Mullan completed his military road, and the region was flooded with thousands of miners and settlers.[5]

The battle is commemorated by the Steptoe Battlefield State Park Heritage Site, where a monument was erected in 1914.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ History of the Northwest Tribes Archived 2007-10-13 at the Wayback Machine, emayzine

- ^ Keenan, Jerry. "Steptoe, Col. Edward Jenner." Encyclopedia of American Indian Wars 1492-1890 Santa Barbara, CA : ABC-CLIO, c1997 p. 223.

- ^ Oregon volunteers battle the Walla Wallas and other tribes beginning on December 7, 1855, HistoryLink, April 20, 2008

- ^ "Battle of Pine Creek", Rosalia, Washington Website, May 3, 2008

- ^ a b c Thompson, Sally (Spring 2018). "John Owen's Worst Trip: A Journey across the Columbia Plateau, 1858". Montana The Magazine of Western History: 29, 31, 35–36.

- ^ May 17, 1858: The Ordeal of the Steptoe Command, HistoryLink, March 30, 2010

Bibliography

[edit]- Hubert H. Bancroft, History Of Washington, Idaho, and Montana, 1845-1889, The History Company, San Francisco, 1890. Chapter V: Indian Wars 1856-1858