Steppe bison

| Steppe bison Temporal range: Mid Middle Pleistocene to Holocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| "Blue Babe", a mummified specimen from Alaska | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Bovinae |

| Genus: | Bison |

| Species: | †B. priscus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Bison priscus | |

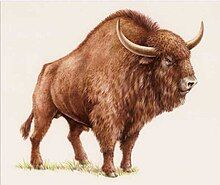

The steppe bison[Note 1] or steppe wisent (Bison priscus)[2] is an extinct species of bison. It was widely distributed across the mammoth steppe, ranging from Western Europe to eastern Beringia in North America during the Late Pleistocene.[3] It is ancestral to all North American bison, including ultimately modern American bison.[4][5] Three chronological subspecies, Bison priscus priscus, Bison priscus mediator, and Bison priscus gigas, have been suggested.[6]

Evolution

[edit]

The steppe bison first appeared during the mid Middle Pleistocene in eastern Eurasia,[7] subsequently dispersing westwards as far as Western Europe.[8] During the late Middle Pleistocene, around 195,000-135,000 years ago, the steppe bison migrated across the Bering land bridge into North America,[4] becoming ancestral to endemic North American bison species, including the largest known bison, the long-horned Bison latifrons, and the smaller Bison antiquus, the latter of which is thought to be ancestral to modern American bison.[5]

Description

[edit]Resembling the modern bison species, especially the American wood bison (Bison bison athabascae),[9] the steppe bison was over 2 m (6 ft 7 in) tall at the withers, reaching 900 kg (2,000 lb) in weight.[10] The tips of the horns were a meter apart, the horns themselves being over half a meter long.

Bison priscus gigas is the largest known bison of Eurasia. This subspecies was possibly analogous to Bison latifrons, attaining similar body sizes and horns which were up to 210 centimeters (83 in) apart, and presumably favored similar habitat conditions.[11]

The steppe bison was also anatomically similar to the European bison (Bison bonasus), to the point of difficulty distinguishing between the two when complete skeletons are unavailable.[12] The two species were close enough to interbreed; however they were also genetically distinct, indicating that interbreeding was in fact rare, possibly as a result of niche partitioning between the species.[12]

Palaeoecology

[edit]Dental microwear analysis suggests the steppe bison was a mixed feeder, rather than a strict grazer.[13] Likely predators of steppe bison include cave hyenas (with steppe bison remains having been found in their dens)[14], cave lions (claw marks were found on the “Blue Babe” mummy and were found to be made by one)[15], as well as scimitar toothed cats and possibly wolves.[16]

Extinction

[edit]

The steppe bison distribution contracted to the north after the end of the last glacial period, surviving into the mid Holocene before becoming extinct as part of the Quaternary extinction event.[9][17] A steppe bison skeleton was radiocarbon dated to 5,400 years Before Present (c. 3450 BCE) in Alaska.[18] B. priscus remains in the northern Angara River in Asia were dated to 2550-2450 BCE,[12] and in the Oyat River in Leningrad Oblast, Russia to 1130-1060 BCE.[19] The causes for the extinction of the steppe bison and many other primarily megafaunal species remain hotly debated, but the selectivity for large animals suggests that the spread of modern humans played a substantial role.[20][21]

Discoveries

[edit]

Steppe bison appear in cave art, notably in the Cave of Altamira and Lascaux, and the carving Bison Licking Insect Bite, and have been found in naturally ice-preserved form.[22][23][24]

Blue Babe is the 36,000-year-old mummy of a male steppe bison which was discovered north of Fairbanks, Alaska, in July 1979.[25] The mummy was noticed by a gold miner who named the mummy Blue Babe – "Babe" for Paul Bunyan's mythical giant ox, permanently turned blue when he was buried to the horns in a blizzard (Blue Babe's own bluish cast was caused by a coating of vivianite, a blue iron phosphate covering much of the specimen).[2] Claw marks on the rear of the mummy and tooth punctures in the skin indicate that Blue Babe was killed by a cave lion. Blue Babe appears to have died during the fall or winter, when it was relatively cold. The carcass probably cooled rapidly and soon froze, which made it difficult for scavengers to eat.[26] Blue Babe is also frequently referenced when talking about scientists eating their own specimens: the research team that was preparing it for permanent display in the University of Alaska Museum removed a portion of the mummy's neck, stewed it, and dined on it to celebrate the accomplishment.[27]

In early September 2007, near Tsiigehtchic, local resident Shane Van Loon discovered a carcass of a steppe bison which was radiocarbon dated to c. 13,650 cal BP.[28] This carcass appears to represent the first Pleistocene mummified soft tissue remains from the glaciated regions of northern Canada.[28]

In 2011, a 9,300-year-old mummy was found at Yukagir in Siberia.[29]

In 2016, a frozen tail was discovered in the north of the Republic of Sakha in Russia. The exact age was not clear, but tests showed it was not younger than 8,000 years old.[30][31] A team of Russian and South Korean scientists proposed extracting DNA from the specimen and cloning it in the future.[30][31]

The steppe wisent is known from Denisova Cave, famous for being the site where the first Denisovan remains were discovered.[32]

References

[edit]- ^ Several literatures address the species as primeval bison.

- ^ Daszkiewicz, Piotr; Samojlik, Tomasz (2019). "Corrected date of the first description of aurochs Bos primigenius (Bojanus, 1827) and steppe bison Bison priscus (Bojanus, 1827)". Mammal Research. 64 (2): 299–300. doi:10.1007/s13364-018-0389-6. ISSN 2199-2401.

- ^ a b "Steppe Bison" Archived 2010-12-12 at the Wayback Machine – Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre. Beringia.com. Retrieved on 2013-05-31.

- ^ Hunting the Extinct Steppe Bison (Bison priscus) Mitochondrial Genome in the Trois-Frères Paleolithic Painted Cave

- ^ a b Froese, Duane; Stiller, Mathias; Heintzman, Peter D.; Reyes, Alberto V.; Zazula, Grant D.; Soares, André E. R.; Meyer, Matthias; Hall, Elizabeth; Jensen, Britta J. L.; Arnold, Lee J.; MacPhee, Ross D. E. (2017-03-28). "Fossil and genomic evidence constrains the timing of bison arrival in North America". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (13): 3457–3462. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.3457F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1620754114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5380047. PMID 28289222.

- ^ a b Zver, Lars; Toškan, Borut; Bužan, Elena (September 2021). "Phylogeny of Late Pleistocene and Holocene Bison species in Europe and North America". Quaternary International. 595: 30–38. Bibcode:2021QuInt.595...30Z. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2021.04.022.

- ^ Castaños, J.; Castaños, P.; Murelaga, X. (2016). "First Complete Skull of a Late Pleistocene Steppe Bison ( Bison priscus ) in the Iberian Peninsula". Ameghiniana. 53 (5): 543–551. doi:10.5710/AMGH.03.06.2016.2995. S2CID 132682791.

- ^ Sorbelli, Leonardo; Alba, David M.; Cherin, Marco; Moullé, Pierre-Élie; Brugal, Jean-Philip; Madurell-Malapeira, Joan (2021-06-01). "A review on Bison schoetensacki and its closest relatives through the early-Middle Pleistocene transition: Insights from the Vallparadís Section (NE Iberian Peninsula) and other European localities". Quaternary Science Reviews. 261: 106933. Bibcode:2021QSRv..26106933S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.106933. ISSN 0277-3791. S2CID 235527116.

- ^ Kahlke, Ralf-Dietrich; García, Nuria; Kostopoulos, Dimitris S.; Lacombat, Frédéric; Lister, Adrian M.; Mazza, Paul P. A.; Spassov, Nikolai; Titov, Vadim V. (2011-06-01). "Western Palaearctic palaeoenvironmental conditions during the Early and early Middle Pleistocene inferred from large mammal communities, and implications for hominin dispersal in Europe". Quaternary Science Reviews. Early Human Evolution in the Western Palaearctic: Ecological Scenarios. 30 (11): 1368–1395. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.1368K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.07.020. ISSN 0277-3791.

- ^ a b Boeskorov, Gennady G.; Potapova, Olga R.; Protopopov, Albert V.; Plotnikov, Valery V.; Agenbroad, Larry D.; Kirikov, Konstantin S.; Pavlov, Innokenty S.; Shchelchkova, Marina V.; Belolyubskii, Innocenty N.; Tomshin, Mikhail D.; Kowalczyk, Rafal; Davydov, Sergey P.; Kolesov, Stanislav D.; Tikhonov, Alexey N.; Van Der Plicht, Johannes (2016). "The Yukagir Bison: The exterior morphology of a complete frozen mummy of the extinct steppe bison, Bison priscus from the early Holocene of northern Yakutia, Russia". Quaternary International. 406: 94–110. Bibcode:2016QuInt.406...94B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.084. S2CID 133244037.

- ^ McPhee, R. D. E. (1999). Extinctions in Near Time: Causes, Contexts, and Consequences. Springer. p. 262. ISBN 978-0306460920.

- ^ C. C. Flerow, 1977, Gigantic Bisons of Asia, Journal of the Palaeontological Society of India, Vol. 20, pp.77-80

- ^ a b c Markova, A. K., Puzachenko, A. Y., Van Kolfschoten, T., Kosintsev, P. A., Kuznetsova, T. V., Tikhonov, A. N., ... & Kuitems, M. (2015). Changes in the Eurasian distribution of the musk ox (Ovibos moschatus) and the extinct bison (Bison priscus) during the last 50 ka BP. Quaternary International, 378, 99-110.

- ^ Hofman-Kamińska, Emilia; Merceron, Gildas; Bocherens, Hervé; Boeskorov, Gennady G.; Krotova, Oleksandra O.; Protopopov, Albert V.; Shpansky, Andrei V.; Kowalczyk, Rafał (14 August 2024). "Was the steppe bison a grazing beast in Pleistocene landscapes?". Royal Society Open Science. 11 (8). doi:10.1098/rsos.240317. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 11321853. PMID 39144492. Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- ^ Rivals, Florent; Baryshnikov, Gennady F.; Prilepskaya, Natalya E.; Belyaev, Ruslan I. (September 2022). "Diet and ecological niches of the Late Pleistocene hyenas Crocuta spelaea and C. ultima ussurica based on a study of tooth microwear". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 601: 111125. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.111125.

- ^ "Blue Babe | Museum | Museum of the North". www.uaf.edu. Retrieved 2025-01-01.

- ^ Bocherens, Hervé (June 2015). "Isotopic tracking of large carnivore palaeoecology in the mammoth steppe". Quaternary Science Reviews. 117: 42–71. Bibcode:2015QSRv..117...42B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.03.018.

- ^ Zazula, Grant D.; Hall, Elizabeth; Hare, P. Gregory; Thomas, Christian; Mathewes, Rolf; La Farge, Catherine; Martel, André L.; Heintzman, Peter D.; Shapiro, Beth (November 2017). "A middle Holocene steppe bison and paleoenvironments from the Versleuce Meadows, Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 54 (11): 1138–1152. Bibcode:2017CaJES..54.1138Z. doi:10.1139/cjes-2017-0100. hdl:1807/78639. ISSN 0008-4077. S2CID 54951935.

- ^ Zazula, Grant D.; Hall, Elizabeth; Hare, P. Gregory; Thomas, Christian; Mathewes, Rolf; La Farge, Catherine; Martel, André L.; Heintzman, Peter D.; Shapiro, Beth (2017). "A middle Holocene steppe bison and paleoenvironments from the Versleuce Meadows, Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 54 (11): 1138–1152. Bibcode:2017CaJES..54.1138Z. doi:10.1139/cjes-2017-0100. hdl:1807/78639. S2CID 54951935.

- ^ Plasteeva, N. A., Gasilin, V. V., Devjashin, M. M., & Kosintsev, P. A. (2020). Holocene Distribution and Extinction of Ungulates in Northern Eurasia. Biology Bulletin, 47(8), 981-995.

- ^ Lemoine, Rhys Taylor; Buitenwerf, Robert; Svenning, Jens-Christian (2023-12-01). "Megafauna extinctions in the late-Quaternary are linked to human range expansion, not climate change". Anthropocene. 44: 100403. Bibcode:2023Anthr..4400403L. doi:10.1016/j.ancene.2023.100403. ISSN 2213-3054.

- ^ Smith, Felisa A.; Elliott Smith, Rosemary E.; Lyons, S. Kathleen; Payne, Jonathan L.; Villaseñor, Amelia (2019-05-01). "The accelerating influence of humans on mammalian macroecological patterns over the late Quaternary". Quaternary Science Reviews. 211: 1–16. Bibcode:2019QSRv..211....1S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.02.031. ISSN 0277-3791.

- ^ Verkaar, E. L. C.; Nijman, IJ; Beeke, M.; Hanekamp, E.; Lenstra, J. A. (2004). "Maternal and Paternal Lineages in Cross-Breeding Bovine Species. Has Wisent a Hybrid Origin?". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (7): 1165–70. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh064. PMID 14739241.

- ^ Dale Guthrie, R (1989). Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe: The Story of Blue Babe. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226311234.

- ^ Paglia, C. (2004). "The Magic of Images: Word and Picture in a Media Age". Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics. 11 (3): 1–22. JSTOR 20163935.

- ^ Deem, James M. "Blue Babe - the 36,000 year-old male bison"[permanent dead link] James M. Deem's Mummy Tombs. 1988-2012. Accessed 20 March 2012.

- ^ "Blue Babe | Museum | Museum of the North". www.uaf.edu. Retrieved 2025-01-01.

- ^ Dale Guthrie, R (1989). Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe: The Story of Blue Babe. University of Chicago Press. p. 298. ISBN 9780226311234.

- ^ a b Zazula, Grant D.; MacKay, Glen; Andrews, Thomas D.; Shapiro, Beth; Letts, Brandon; Brock, Fiona (2009). "A late Pleistocene steppe bison (Bison priscus) partial carcass from Tsiigehtchic, Northwest Territories, Canada". Quaternary Science Reviews. 28 (25–26): 2734–2742. Bibcode:2009QSRv...28.2734Z. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.06.012. ISSN 0277-3791.

- ^ Palermo, Elizabeth (6 November 2014). "9,000-Year-Old Bison Mummy Found Frozen in Time". www.livescience.com. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ a b "The remains of an 8,000 year old lunch: an extinct steppe bison's tail". siberiantimes.com. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ a b "Cloning ancient extinct bison sounds like sci-fi, but scientists hope to succeed within years". International Business Times UK. 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ Puzachenko, A.Yu.; Titov, V.V.; Kosintsev, P.A. (20 December 2021). "Evolution of the European regional large mammals assemblages in the end of the Middle Pleistocene – The first half of the Late Pleistocene (MIS 6–MIS 4)". Quaternary International. 605–606: 155–191. Bibcode:2021QuInt.605..155P. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.08.038. Retrieved 13 January 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- Bison

- Prehistoric bovids

- Holocene extinctions

- Prehistoric Artiodactyla

- Prehistoric mammals of North America

- Quaternary mammals of Asia

- Pleistocene mammals of Europe

- Pleistocene mammals of Asia

- Pleistocene mammals of North America

- Mammals described in 1827

- Fossil taxa described in 1827

- Pleistocene first appearances

- Taxa named by Ludwig Heinrich Bojanus

- Species made extinct by human activities