St. Albert, Alberta

St. Albert | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of St. Albert | |

View of Downtown St. Albert | |

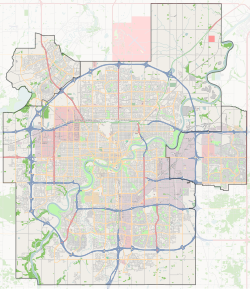

City boundaries | |

| Coordinates: 53°38′13″N 113°37′13″W / 53.63694°N 113.62028°W[1] | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Alberta |

| Region | Edmonton Metropolitan Region |

| Adjacent municipal district | Sturgeon County |

| Founded | 1861 |

| Incorporated[2] | |

| • Village | December 7, 1899 |

| • Town | September 1, 1904 |

| • New town | January 1, 1957 |

| • Town | July 3, 1962 |

| • City | January 1, 1977 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Cathy Heron |

| • Governing body |

|

| • CAO | William Fletcher |

| • MP | Michael Cooper (St. Albert—Edmonton-CPC) |

| • MLA | Marie Renaud (St. Albert-NDP) Dale Nally (Morinville-St. Albert-UCP) |

| Area (2021)[4] | |

| • Land | 47.84 km2 (18.47 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 689 m (2,260 ft) |

| Population (2021)[4] | |

• Total | 68,232 |

| • Density | 1,426.4/km2 (3,694/sq mi) |

| • Municipal census (2018) | 66,082[6] |

| • Estimate (2020) | 69,335[7] |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| Forward sortation area | |

| Area code(s) | 780, 587, 825, 368 |

| Highways | |

| Waterways | Sturgeon River, Big Lake |

| Website | Official website |

St. Albert is a city in Alberta, Canada, located on the Sturgeon River, northwest of the City of Edmonton, the provincial capital. It was originally settled as a Métis community, and is now the second-largest city in the Edmonton Metropolitan Region. St. Albert first received its town status in 1904 and was reached by the Canadian Northern Railway in 1906.[8] Originally separated from Edmonton by several miles of farmland, the 1980s expansion of Edmonton's city limits placed St. Albert immediately adjacent to the larger city on St. Albert's southern and eastern sides.

History

[edit]

St. Albert was founded in 1861 as a Métis settlement by Father Albert Lacombe, OMI, who built a small chapel, the Father Lacombe Chapel, in the Sturgeon River valley. The chapel still stands to this day on Mission Hill in St. Albert. The original settlement was named Saint Albert by Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché, OMI, after Lacombe's name saint, Saint Albert of Louvain. Originally, although Lacombe had intended to found the mission at Lac Ste. Anne, the soil proved infertile, thus he moved the settlement to what would become St. Albert. This location offered several advantages, notably its easy access to supplies of wood and water, in addition to its excellent soil, it being a regular stopping-point for First Nations peoples on their travels, and its proximity to Fort Edmonton, where the priests could purchase necessary supplies and minister to Catholic workers. A few years later, a group of Grey Nuns would follow Lacombe from Lac Ste. Anne. More Métis from Lac Ste. Anne arrived in 1863 and, by December 1864, the population was roughly 300. In 1870, localised outbreaks of smallpox had spread northward into St. Albert, killing 320 of the area's then-900 residents.[9][10]

St. Albert was previously the site of two Indian residential schools[11] as part of the Canadian Residential School System. The St. Albert Indian Residential School ("Youville") was located on Mission Hill within the St. Albert city limits and was operated by the Roman Catholic Church from October 22, 1873, to June 30, 1948, after being relocated from the Lac Ste. Anne Mission, the site of its original founding.[12] The Edmonton Indian Residential School ("Poundmaker") was located approximately 6 km east of St. Albert's current downtown area, and was operated by the Methodist Church from March 1, 1924, to June 30, 1968,[13] later becoming the home of the Poundmaker Lodge rehabilitation centre. Between the two schools, 53 students are known to have died under unknown or dubious circumstances while in attendance.[14][15] A healing garden, named Kâkesimokamik, was opened on September 15, 2017, as part of the truth-and-reconciliation process between the city of St. Albert and survivors (and their descendants) of the residential school system.[16]

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, it was mistakenly assumed that the community had been named after St. Albert the Great, due to incorrectly-printed information in the 1985 history of St. Albert, The Black Robe's Vision,[17] published by amateur historians of the St. Albert Historical Society. This led to the City of St. Albert erroneously promoting St. Albert the Great as the community's "patron saint", even erecting a statue of the incorrect saint in the downtown area. However, the misconception was not corrected until 2008.[18] The original chapel has since become an historic site, staffed with historical interpreters, and is open to the public during the summer season.

Also located in St. Albert is the St. Albert Grain Elevator Park, featuring two historic grain elevators; the original grain elevator was constructed in 1906 by the Brackman-Ker Milling Company, with the other being built later, in 1929, by The Alberta Wheat Pool company. The original 1906 elevator was originally red in colour, but has faded with time to a metallic silver. There is also a reproduction of the original 1909 railway station housed at Grain Elevator Park, erected in 2005. On Madonna Drive stands the Little White School House, which is open to the public. Arts and Heritage – St. Albert maintains the site, as well as the Grain Elevators and other heritage buildings, in addition to other sites under-restoration in the city. In June 2009, the City Council approved a multi-staged plan for the heritage sites, featuring the restoration of the grain elevators and the opening of both a Métis and French Canadian farm on adjacent lots by the River.

Economy

[edit]St. Albert has an active and skilled labour force with a low unemployment rate of 4.3%. In 2011, 67.5% of the 40,560 adults aged 25 years and over in St. Albert had completed some form of postsecondary education, compared with 59.6% at the national level.

Of the population aged 25 years and over in St. Albert, 31.7% had a university certificate or degree. An additional 24.3% had a college diploma and 11.6% had a trades certificate.

The share of the adult population that had completed a high school diploma as their highest level of educational attainment was 23.7%, and 8.8% had completed neither high school nor any postsecondary certificates, diplomas or degrees.[19]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 472 | — |

| 1906 | 543 | +15.0% |

| 1911 | 614 | +13.1% |

| 1916 | 655 | +6.7% |

| 1921 | 800 | +22.1% |

| 1926 | 684 | −14.5% |

| 1931 | 825 | +20.6% |

| 1936 | 811 | −1.7% |

| 1941 | 697 | −14.1% |

| 1946 | 804 | +15.4% |

| 1951 | 1,129 | +40.4% |

| 1956 | 1,320 | +16.9% |

| 1961 | 4,059 | +207.5% |

| 1966 | 9,736 | +139.9% |

| 1971 | 11,800 | +21.2% |

| 1976 | 24,129 | +104.5% |

| 1981 | 31,996 | +32.6% |

| 1986 | 36,710 | +14.7% |

| 1991 | 42,146 | +14.8% |

| 1996 | 46,888 | +11.3% |

| 2001 | 53,081 | +13.2% |

| 2006 | 57,719 | +8.7% |

| 2011 | 61,466 | +6.5% |

| 2016 | 65,589 | +6.7% |

| 2021 | 68,232 | +4.0% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30] [31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][4] | ||

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the City of St. Albert had a population of 68,232 living in 25,938 of its 27,019 total private dwellings, a change of 4% from its 2016 population of 65,589. With a land area of 47.84 km2 (18.47 sq mi), it had a population density of 1,426.3/km2 (3,694.0/sq mi) in 2021.[4]

In the 2016 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the City of St. Albert had a population of 65,589 living in 23,954 of its 24,446 total private dwellings, a change of 6.7% from its 2011 population of 61,466. With a land area of 48.45 km2 (18.71 sq mi), it had a population density of 1,353.7/km2 (3,506.2/sq mi) in 2016.[42]

The population of the City of St. Albert according to its 2018 municipal census is 66,082,[6] a change of 2.2% from its 2016 municipal census population of 64,645.[43]

Ethnicity

[edit]In 2021,[44] 83.4% of residents were white/European, 11.1% were visible minorities and 5.5% were Indigenous. The largest visible minority groups were Filipino (3.1%), South Asian (1.7%), Black (1.5%), Chinese (1.3%), and Arab (1.0%).

| Panethnic group | 2021[45] | 2016[46] | 2011[47] | 2006[48] | 2001[49] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| European[a] | 55,835 | 83.4% | 55,850 | 86.7% | 54,260 | 89.72% | 53,185 | 92.75% | 49,305 | 93.43% |

| Indigenous | 3,685 | 5.5% | 2,830 | 4.39% | 2,205 | 3.65% | 1,640 | 2.86% | 1,220 | 2.31% |

| Southeast Asian[b] | 2,335 | 3.49% | 1,630 | 2.53% | 835 | 1.38% | 320 | 0.56% | 530 | 1% |

| South Asian | 1,170 | 1.75% | 915 | 1.42% | 875 | 1.45% | 470 | 0.82% | 490 | 0.93% |

| East Asian[c] | 1,120 | 1.67% | 900 | 1.4% | 810 | 1.34% | 745 | 1.3% | 605 | 1.15% |

| African | 1,035 | 1.55% | 800 | 1.24% | 530 | 0.88% | 245 | 0.43% | 260 | 0.49% |

| Middle Eastern[d] | 775 | 1.16% | 770 | 1.2% | 450 | 0.74% | 435 | 0.76% | 205 | 0.39% |

| Latin American | 605 | 0.9% | 370 | 0.57% | 285 | 0.47% | 155 | 0.27% | 85 | 0.16% |

| Other/multiracial[e] | 380 | 0.57% | 350 | 0.54% | 235 | 0.39% | 165 | 0.29% | 70 | 0.13% |

| Total responses | 66,945 | 98.11% | 64,415 | 98.21% | 60,480 | 98.4% | 57,345 | 99.35% | 52,770 | 99.41% |

| Total population | 68,232 | 100% | 65,589 | 100% | 61,466 | 100% | 57,719 | 100% | 53,081 | 100% |

| Note: Totals greater than 100% due to multiple origin responses | ||||||||||

Language

[edit]As of 2021, 86.0% of residents spoke English as their mother tongue in 2021. The next most common first languages were French (2.6%), Tagalog (1.5%), German (0.8%), Spanish (0.7%) Ukrainian (0.6%), Chinese languages (0.6%), and Arabic (0.5%). 1.3% of the population listed both English and a non-official language as mother tongues, while 0.7% listed both English and French.

Religion

[edit]According to the 2021 census, 55.4% of residents were Christian, down from 68.3% in 2011.[50] 27.9% were Catholic, 13.6% were Protestant, 8.3% were Christian n.o.s, 1.4% were Christian Orthodox and 4.2% belonged to other Christian denominations and Christian-related traditions. 41.3% were non-religious or secular, up from 28.8% in 2011. All other religions and spiritual traditions accounted for 3.0% of the population. The largest non-Christian religions were Islam (1.6%) and Hinduism (0.4%).

Arts and culture

[edit]Located in the heart of downtown, St. Albert Place is the focal point of many community events and activities. Designed by world-renowned Canadian architect Douglas Cardinal, its sculptural symmetry mimics the curves of the Sturgeon River that runs behind it. There are no corners; only curves. Built in 1984, St. Albert Place was designed as a "people place", housing a unique combination of civic government and cultural activity. Currently it houses the St. Albert Public Library, Musée Héritage Museum, Visual Arts Studio and Arden Theatre, as well as City Hall and associated city government services. The Musée Héritage Museum celebrates and explores the story of St. Albert through a variety of programs which seek to preserve the community's history for the future. The museum houses both permanent and temporary exhibits and also contains a Children's Discovery Room and gift shop. The archives at the museum consist of over 6,500 artifacts, 1,100 programming objects, 70 linear metres of textual record, around 3,000 pre-1948 photographs and thousands of post-1948 photographs. The museum is operated by Arts and Heritage St. Albert.[51]

St. Albert has a rich arts scene. St. Albert is home to a writers' guild and painters' guild and renowned bands like Social Code and Tupelo Honey hail from St. Albert. The Arden Theatre is a popular venue for many plays and musical performances.

The St. Albert public art gallery, Art Gallery of St. Albert is a focal point of St. Albert's downtown. The gallery is housed in the historical Banque d'Hochelaga building in the heart of downtown St. Albert. The gallery features monthly exhibitions, a variety of public programs and also runs an annual art auction in St Albert. The Art Gallery of St. Albert is one of the stops on the St. Albert ArtWalk. The gallery is operated by Arts and Heritage St. Albert.[52]

St. Albert is also notable for its Aboriginal heritage. The city is home to the Michif Institute founded by former Senator Thelma Chalifoux, dedicated to preserving and spreading knowledge of the city's Métis background. The Musée Héritage Museum contains many Métis artifacts. Many of the street signs in the city's downtown core are also trilingual, written in French and Cree in addition to English, as a tribute to the city's multiracial and multilinguistic origins. A current city project is to replace English-only signs with trilingual versions as the English-only versions wear out.[citation needed]

In 2008, NBC decided to film portions of its new horror/suspense anthology series Fear Itself in St. Albert's downtown and river valley.[53]

St. Albert also has a St. Albert Children's Theatre group putting on two large musicals a year with many summer camps to participate in.

St. Albert is home to the St. Albert Community Band, whose motto is "Music is for Life!"[54]

Festivals and events

[edit]

The Kinsmen Rainmaker Rodeo starts with a parade that winds its way through the heart of St. Albert. After the parade, the rodeo begins, with rodeo events, midway, and musical performances.

The Outdoor Farmers' Market, held in downtown St. Albert, is Western Canada's largest outdoor farmers' market, attracting 10,000 to 15,000 people every Saturday from June to October. You can find locally grown fresh produce, handmade products and crafts and listen to the music of the buskers.

As many as 6,000 participants come to St. Albert to enjoy Rock'n August, a five-day festival held to celebrate the rumbles of chrome pipes and the rim shots of classic Rock and Roll music.

Other annual events include the St. Albert Rotary Music Festival, and Mambos & Mocktails, a 3-hour jazz concert played every December at Bellerose Composite High School by the jazz band and choir.

St. Albert also host an annual Harvest Festival at the St. Albert Grain Elevator Park.

The Cheremosh Ukrainian Dance Festival, held at the Arden Theatre is one of the largest dance festivals of its kind in North America. It is hosted annually by the Cheremosh Ukrainian Dance Company and generally takes place during the second weekend in May.[55]

Library services

[edit]The St. Albert Public Library (SAPL) is located in St. Albert Place in the heart of downtown. The Library provides a wide range of services for St. Albert residents and visitors, including lending materials such as books, CDs and DVDs, providing digital resources such as downloadable eBooks and eAudiobooks, databases and streaming products, providing services such as public computing and WiFi access and presenting learning opportunities such as children's storytimes, adult programs and educational sessions including technology training.

Sports and recreation

[edit]

- Parks

The city has over 100 parks and playgrounds[57] The Red Willow park trail system winds its way all through St. Albert and connects many parks, schools, and residential areas, including Lacombe Lake Park.

- Facilities

In September 2006, a $42.77-million multi-purpose leisure centre, Servus Credit Union Place, was built. It features a recreational aquatic centre, a kid's play area, the Troy Murray, Mark Messier and Go Auto Arenas, two indoor soccer/lacrosse fields, three basketball courts, a large exercise room, and a running track among other amenities. Construction of the facility, touted as an eventual break-even operation, was approved via plebiscite during the 2004 municipal election.

Servus Credit Union Place served as an expansion of the original Campbell Twin Arenas, which housed the Mark Messier and Troy Murray hockey rinks built in 1992, named for those two local National Hockey League (NHL) players. There was some controversy in 2006 when the city announced that they would rename the two existing rinks, and were going to offer those naming rights for sale. Following coverage of the controversy surfacing in Sports Illustrated, then mayor Paul Chalifoux decided to repeal the decision.[58] The twin arenas were upgraded concurrent with the construction of Servus Credit Union Place.

A smaller pair of ice hockey arenas, the Kinex and Akinsdale arenas, were opened side by side in 1982 in the Akinsdale neighbourhood.[59] The Akinsdale Arena served as the city's main arena until the opening of the Campbell Twin Arenas. In August 2019, a ceremony was held renaming Akinsdale Arena after retired NHL star Jarome Iginla, who played his minor hockey in St. Albert until leaving to the Western Hockey League as a 16-year-old.[60]

There is also Fountain Park pool and Grosvenor pool, both offering a variety of pools, tennis courts, racketball courts and child play areas.

- Hockey

St. Albert was twice formerly home to an Alberta Junior Hockey League (AJHL) franchise. Between 1977 and 2004, it was home to the St. Albert Saints, which produced players such as Mark Messier and Mike Comrie. The team moved to Spruce Grove in 2004, becoming the Spruce Grove Saints. In 2007, the AJHL returned to St. Albert when the Fort Saskatchewan Traders relocated to the city, becoming the St. Albert Steel. Playing out of Servus Credit Union Place, the team lasted five seasons before moving to Whitecourt in 2012, becoming the Whitecourt Wolverines.

NHL ice hockey player Jarome Iginla is from St. Albert. He played his entire minor hockey career in the St. Albert Minor Hockey Association, which included stints with the Bantam AAA Sabres and the Midget AAA Raiders. It was during the 1992–93 season with the Raiders that Iginla, then an under-age midget player, scored 87 points to lead the Alberta Midget AAA Hockey league in scoring. Following this season Iginla joined the Kamloops Blazers as a 16-year-old.

Other hockey players that have played in St. Albert are Rob Brown, Geoff Sanderson, Fernando Pisani, Paul Comrie, Stu Barnes, Brian Benning, Matt Benning, Steven Goertzen, René Bourque, Jamie Lundmark, Erik Christensen, Steve Reinprecht, Todd Ewen, Dion Phaneuf, Drew Stafford, Nick Holden, Emanuel Viveiros, Colton Parayko, Tyson Jost, Josh Mahura, and Joe Benoit.

- Football

St. Albert recently added an artificial turf field in Riel Park as the home of every minor team in the city.

- Cross Country Skiing

St Albert has cross country skiing along the Sturgeon River and at River Lot 56 Natural Area – Stanski. River Lot 56 is across from the NE corner of Sir Winston Churchhill Ave and Poundmaker Rd and has professionally groomed multiple loop trails with interpretive signs and maps.[61]

- Soccer

SASA Impact FC operated by the St. Albert Soccer Association has a pro-am women's team in the US-based United Women's Soccer.

Government

[edit]St. Albert has traditionally elected members of the Conservative Party of Canada to the federal legislature. After the rise of the Reform Party of Canada and its subsequent change to the Canadian Alliance, John G. Williams was elected and served five terms as the city's Member of Parliament, becoming a Conservative MP after the Alliance's 2003 merger with the Progressive Conservative Party, before stepping down in 2008. Michael Cooper, of the Conservative Party of Canada, is the current Member of Parliament for St. Albert.

Provincially, most of St. Albert is currently represented by an Alberta New Democratic Party MLA (Marie Renaud) in the legislature, as well a United Conservative Party MLA representing the Northern part of the city and Morinville. In previous elections, it has alternated between Liberal and Conservative representatives.

St. Albert's governing body is composed of a mayor (currently Cathy Heron) and six city councillors. Municipal elections are held every four years. The last was held on October 18, 2021, and the next will be held on October 20, 2025.[62]

Flag

[edit]St. Albert's flag is a red, white and blue design, with a stylized coat of arms located on the upper hoist. It was chosen by St. Albert's citizens in a citywide ballot, and was approved by the City Council in 1980. The blue and white, colours shared with Quebec, represents the Francophones and Métis peoples who first settled St. Albert. The red, white, and blue symbolizes Great Britain and the Anglophones that further shaped St. Albert.[63]

Education

[edit]

K-12 education

[edit]School districts

- St. Albert Public Schools: Serving over 6000 students taught in a non-denominational setting. In St. Albert, St. Albert Public Schools' high school students attend Bellerose Composite High School or Paul Kane High School. Constitution Act, 1867; Alberta Act, 1905.[64]

- Greater St. Albert Catholic Schools: This separate school division operates 17 schools and serves approximately 7600 students. In St. Albert, GSACRD's high school students attend ESSMY or St. Albert Catholic High School.[65]

St. Albert is also home to two schools from the North Central Francophone School Board. Their schools are "École La Mission" (K-6) located in the Heritage Lakes subdivision and "École Alexandre-Taché" (7–12), located in the Erin Ridge subdivision. This school jurisdiction has minority language rights assured by the Constitution Act, 1982 (section 23).

Continuing education

[edit]St. Albert Further Education, known as "Further Ed", provides learning opportunities to the residents of St. Albert.[66]

The STAR Literacy Program matches volunteer tutors with adults who wish to improve their reading and writing skills.

Media

[edit]There are currently two periodicals published in St. Albert: the biweekly newspaper St. Albert Gazette, and the monthly magazine T8N.

The first publication in St. Albert was a French newspaper called Le Progrès, which began publishing in 1909. The bilingual St. Albert Star, or Étoile de St. Albert, was started in 1912, and offered issues in both English and French. The two versions of the paper would often carry unique stories that the other did not. In 1914, The Star ceased printing, and Le Progrès relocated to Edmonton.

It wasn't until 1949 that the next newspaper began publishing, which saw the first issue by the St. Albert Gazette. That version of the newspaper merged with the Morinville Journal in 1953. In 1961 a new newspaper with the same name was started. That version has undergone a number of name changes through the years, but is the one that exists today.[67]

In 1998, the Saint City News was founded, operating as the Gazette's major competitor for 13 years until it closed in 2011.[68]

Also in 2011, the St. Albert Leader was started. It was distributed for a short time, but stopped printing in 2015.[69]

The long form monthly magazine T8N began distribution in 2014, and covers topics about the city and its people.[67]

Radio

[edit]

The first radio station in St. Albert came in 1978. The oldies station CKST Radio broadcast on frequency 1070 AM until it changed its callsign to CFMG in 1988. It was at this point that it began broadcasting on the 1200 AM frequency.[70] The station would make another change in 1995, branding itself with the name EZ Rock. The change also saw the station move from AM radio to FM, broadcasting on 104.9 FM.[71] The station was sold to Astral Media in 2007.[72]

St. Albert lost the radio station after its most recent change in 2011, when it moved to Edmonton after changing formats from adult contemporary to top 40, becoming 104.9 Virgin Radio.[67]

Due to the city's adjacency to Edmonton, all major Edmonton media—newspapers, television, and radio—also serve St. Albert.

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]The nearest airport providing passenger service is the Edmonton International Airport. Local air services are provided by the St. Albert Heliport to the northwest of the city[73] and Villeneuve Airport to the west, while Sturgeon Community Hospital has a helipad to receive and transfer patients.

Public transit

[edit]The city runs St. Albert Transit (StAT) a public transport agency. It runs 21 local routes and 7 commuter routes to Edmonton.[74] Village Transit Station is located at Gate Avenue and Grange Drive. St. Albert Exchange is located at Rivercrest Crescent and St. Vital Avenue. The Metro Line in Edmonton could be extended to St. Albert with four stations within city limits.

Notable people

[edit]- Hercules Ayala, Puerto Rican born professional wrestler

- Hailey Benedict, country music singer-songwriter

- Rob Brown, NHL ice hockey player

- Kirby Dach, NHL ice hockey player

- Daryl Harr, racing driver

- Nick Holden, NHL ice hockey player

- Don Iveson, former Mayor of Edmonton

- Jarome Iginla, NHL ice hockey player, Olympic ice hockey medallist (x2)

- Tyson Jost, NHL ice hockey player

- Marc Kennedy, curler, Olympic curling medallist (x2)

- Mark Messier, NHL ice hockey player, Stanley Cup champion (x6)

- Meaghan Mikkelson, PWHPA ice hockey player, Olympic ice hockey medallist (x3)

- Colton Parayko, NHL ice hockey player, Stanley Cup champion (x1)

- Jason Thompson, Actor/Model.

- Josh Mahura, NHL ice hockey player, Stanley Cup Champion (x1)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Statistic includes all persons that did not make up part of a visible minority or an indigenous identity.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Filipino" and "Southeast Asian" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Chinese", "Korean", and "Japanese" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "West Asian" and "Arab" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Visible minority, n.i.e." and "Multiple visible minorities" under visible minority section on census.

References

[edit]- ^ "St. Albert". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ "Location and History Profile: City of St. Albert" (PDF). Alberta Municipal Affairs. June 17, 2016. p. 113. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ "Municipal Officials Search". Alberta Municipal Affairs. May 9, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities)". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ "Alberta Private Sewage Systems 2009 Standard of Practice Handbook: Appendix A.3 Alberta Design Data (A.3.A. Alberta Climate Design Data by Town)" (PDF) (PDF). Safety Codes Council. January 2012. pp. 212–215 (PDF pages 226–229). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ a b 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List (PDF). Alberta Municipal Affairs. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4601-4254-7. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ "Census Subdivision (Municipal) Population Estimates, July 1, 2016 to 2020, Alberta". Alberta Municipal Affairs. March 23, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Edmonton Bulletin, September 27, 1906.

- ^ Goyette, Linda (2004). Edmonton in Our Own Words. p. 93.

- ^ Fromhold, Joachim. Alberta History: The Old North Trail (Cree Trail) 15,000 Years of Indian History 1850–1870 Part 2. p. 346.

- ^ ""Residential Schools", City of St. Albert website". Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ ""IRSHDC: School: St. Albert (AB) [18697]", Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre website". Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ ""IRSHDC: School: Edmonton (AB) [1768],Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre website". Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ ""Edmonton (Poundmaker) – NCTR", National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation website". Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ ""St. Albert (Youville) – NCTR", National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation website". Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ ""Opening and Celebration", City of St. Albert website". Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ The Black Robe's Vision

- ^ Kevin Ma (November 15, 2008). "The Saints Called Albert". St. Albert Gazette. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009.

- ^ "NHS Focus on Geography Series – St. Albert". NHS Focus on Geography Series – St. Albert. Statistics Canada. October 23, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- ^ "Table IX: Population of cities, towns and incorporated villages in 1906 and 1901 as classed in 1906". Census of the Northwest Provinces, 1906. Vol. Sessional Paper No. 17a. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1907. p. 100.

- ^ "Table I: Area and Population of Canada by Provinces, Districts and Subdistricts in 1911 and Population in 1901". Census of Canada, 1911. Vol. I. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1912. pp. 2–39.

- ^ "Table I: Population of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta by Districts, Townships, Cities, Towns, and Incorporated Villages in 1916, 1911, 1906, and 1901". Census of Prairie Provinces, 1916. Vol. Population and Agriculture. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1918. pp. 77–140.

- ^ "Table 8: Population by districts and sub-districts according to the Redistribution Act of 1914 and the amending act of 1915, compared for the census years 1921, 1911 and 1901". Census of Canada, 1921. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1922. pp. 169–215.

- ^ "Table 7: Population of cities, towns and villages for the province of Alberta in census years 1901–26, as classed in 1926". Census of Prairie Provinces, 1926. Vol. Census of Alberta, 1926. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1927. pp. 565–567.

- ^ "Table 12: Population of Canada by provinces, counties or census divisions and subdivisions, 1871–1931". Census of Canada, 1931. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1932. pp. 98–102.

- ^ "Table 4: Population in incorporated cities, towns and villages, 1901–1936". Census of the Prairie Provinces, 1936. Vol. I: Population and Agriculture. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1938. pp. 833–836.

- ^ "Table 10: Population by census subdivisions, 1871–1941". Eighth Census of Canada, 1941. Vol. II: Population by Local Subdivisions. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1944. pp. 134–141.

- ^ "Table 6: Population by census subdivisions, 1926–1946". Census of the Prairie Provinces, 1946. Vol. I: Population. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1949. pp. 401–414.

- ^ "Table 6: Population by census subdivisions, 1871–1951". Ninth Census of Canada, 1951. Vol. I: Population, General Characteristics. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1953. p. 6.73–6.83.

- ^ "Table 6: Population by sex, for census subdivisions, 1956 and 1951". Census of Canada, 1956. Vol. Population, Counties and Subdivisions. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1957. p. 6.50–6.53.

- ^ "Table 6: Population by census subdivisions, 1901–1961". 1961 Census of Canada. Series 1.1: Historical, 1901–1961. Vol. I: Population. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1963. p. 6.77–6.83.

- ^ "Population by specified age groups and sex, for census subdivisions, 1966". Census of Canada, 1966. Vol. Population, Specified Age Groups and Sex for Counties and Census Subdivisions, 1966. Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1968. p. 6.50–6.53.

- ^ "Table 2: Population of Census Subdivisions, 1921–1971". 1971 Census of Canada. Vol. I: Population, Census Subdivisions (Historical). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1973. p. 2.102–2.111.

- ^ "Table 3: Population for census divisions and subdivisions, 1971 and 1976". 1976 Census of Canada. Census Divisions and Subdivisions, Western Provinces and the Territories. Vol. I: Population, Geographic Distributions. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1977. p. 3.40–3.43.

- ^ "Table 4: Population and Total Occupied Dwellings, for Census Divisions and Subdivisions, 1976 and 1981". 1981 Census of Canada. Vol. II: Provincial series, Population, Geographic distributions (Alberta). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1982. p. 4.1–4.10. ISBN 0-660-51095-2.

- ^ "Table 2: Census Divisions and Subdivisions – Population and Occupied Private Dwellings, 1981 and 1986". Census Canada 1986. Vol. Population and Dwelling Counts – Provinces and Territories (Alberta). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1987. p. 2.1–2.10. ISBN 0-660-53463-0.

- ^ "Table 2: Population and Dwelling Counts, for Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions, 1986 and 1991 – 100% Data". 91 Census. Vol. Population and Dwelling Counts – Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1992. pp. 100–108. ISBN 0-660-57115-3.

- ^ "Table 10: Population and Dwelling Counts, for Census Divisions, Census Subdivisions (Municipalities) and Designated Places, 1991 and 1996 Censuses – 100% Data". 96 Census. Vol. A National Overview – Population and Dwelling Counts. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1997. pp. 136–146. ISBN 0-660-59283-5.

- ^ "Population and Dwelling Counts, for Canada, Provinces and Territories, and Census Divisions, 2001 and 1996 Censuses - 100% Data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2006 and 2001 censuses – 100% data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. January 6, 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2011 and 2006 censuses". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- ^ a b "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data (Alberta)". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ 2016 Municipal Affairs Population List (PDF). Alberta Municipal Affairs. ISBN 978-1-4601-3127-5. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (February 9, 2022). "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - St. Albert, City (CY) [Census subdivision], Alberta". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 27, 2021). "Census Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (November 27, 2015). "NHS Profile". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (August 20, 2019). "2006 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (July 2, 2019). "2001 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (May 8, 2013). "2011 National Household Survey Profile – Census subdivision". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Musée Héritage Museum – About Us". Musée Héritage Museum. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ "Art Gallery of St. Albert – About Us". Art Gallery of St. Albert. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ "NBC to film series in St. Albert". CTV Edmonton. March 7, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ "St. Albert Community Band". St. Albert Community Band. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ "Cheremosh Ukrainian Dance Festival". Cheremosh Ukrainian Dance Company. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ "St. Albert Heritage Sites". City of St. Albert. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ Shankowsky, Josh. "10 Reasons Why You Should Relocate to St. Albert Canada". Bermont Realty. Snap SEO.

- ^ Harding, Katherine (August 25, 2006). "Rinks to keep hockey heroes' names". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ^ "Jarome Iginla / Kinex Arenas". City of St. Albert. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- ^ Heidenreich, Phil (August 16, 2019). "St. Albert arena to be renamed after hometown hockey hero Jarome Iginla". Global News. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- ^ "Riverlot 56 Natural Area – Stanski near St. Albert, AB – a snowshoeing, hiking and cross country skiing trail". www.trailpeak.com.

- ^ "Election Information / City of St. Albert". City of St. Albert. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "City Emblems and Symbols" (PDF). p. 7. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "St. Albert Public Schools". Spschools.org. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ Greater St. Albert Catholic Schools. "Greater St. Albert Catholic Schools". Gsacrd.ab.ca. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ "General Information". St. Albert Further Education. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ a b c "St.Albert Media". T8N. May 30, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ "Saint City News shuts down". StAlbertToday.ca. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ Cory Hare (July 2, 2011). "Saint City News shuts down". stalbertgazette.com. St. Albert Gazette. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ Government of Canada, Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) (August 5, 1988). "ARCHIVED – Acquisition of assets – Balsa Broadcasting Corporation". crtc.gc.ca. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ Government of Canada, Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) (1994). "ARCHIVED – Decision CRTC 94–436". crtc.gc.ca. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ "CRTC approves Astral/Standard transaction". Archived from the original on December 24, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ^ "Sturgeon County and City of St. Albert Intermunicipal Development Plan" (PDF) (PDF). City of St. Albert. May 2001. p. 13 of 63. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ^ "St. Albert Transit". City of St. Albert.