Spontaneous trait inference

Spontaneous trait inference is the term utilised in social psychology to describe the mechanism that causes individuals to form impressions of people, based on behaviours they witness them exhibiting.[1][2] The inferences being made are described as being extrapolated from the behaviour, as the link between the inferred trait and the perceived behaviour is not substantiated, only vaguely implied.[1] The inferences that are made are spontaneous and implicitly formed, with the cognitive mechanism acting almost reflexively.[3]

Research into spontaneous trait inference began with Hermann von Helmholtz and his unconscious inference[4] postulation.[5] He first formed this concept to describe human perception of optical illusions, and then in his third volume of "The Treatise on Physiological Optics", connected the concept to social psychology and human interaction.[6] However, his concept of unconscious inference was widely criticised, and has since been refined as spontaneous trait inference.[5]

In experimental research, there have been multiple ways in which spontaneous trait inference has been observed and measured. These include the cued recall paradigm, the picture priming paradigm, and the word fragment completion paradigm.[1][7] Research of the applications of spontaneous trait inference, has been of recent interest amongst social psychologists. Studies have been conducted which have found that despite the circumstantial differences, between social media interaction and physical interaction, spontaneous trait inference is still prevalent.[8] It has also been found that individuals raised in collectivist cultures form different inference to those raised individualist cultures, despite being witnessing the same behaviour.[9]

Spontaneous trait inference has numerous and widespread implications. With the formation of unsubstantiated conclusions based on a single behaviour, an individual formulates an inaccurate perception of the person being observed.[1] This can, in turn, influence interactions with the person and treatment of them. Spontaneous trait inference has been centralised as a key concept of social psychology, as it forms the foundation of models for other psychological phenomena, such as Fundamental attribution error (also known as correspondence bias) and belief perseverance.[1]

Overview

[edit]Spontaneous trait inference refers to the phenomena where, when a behaviour is observed by an individual, they extrapolate trait inferences that aren't actually known to them through that observation alone.[1] For example, an individual that would see a stranger on the bus reading a book would infer them to be smart or intellectual, or an individual who witnesses a person not keeping the door open for the people behind them, would make the inference that they are impolite.

The distinctiveness of spontaneous trait inference is that the inference being made about the individual is not strictly connected with the behaviour witnessed, and are not indicative of the individual's personality, circumstance or natural behaviour.[1] Perhaps the stranger on the bus who was reading the book had to read it for educational purposes, and maybe the person who didn't keep the door open was in a rush. It is logical to conclude that a single behaviour exhibited by a person should not be the basis for a general trait, however spontaneous trait inference is a mechanism that goes against this ideal.

Another novelty of spontaneous trait inference, is that it occurs unintentionally without specific instruction or purpose to do so. It is also considered to be reflexive, a reactionary conclusion made by an individual when witnessing a behaviour,[1][3] however they are not automatic.[2] Also spontaneous trait inferences have been found to be much stronger when the inference being made aligns with a prevailing stereotype.[1] For example, the trait of “bread-winner” is significantly more likely to attributed to a male than a female, as the notion of men being sole providers is ingrained within gender stereotypes.

Spontaneous trait inference is a concept explored widely within social psychology, as it has broad implications on the how and why humans interact the way they do and the impressions that are formed in a social setting.[7] Spontaneous trait inference is an area that is linked to other psychology theories, such as, attribution theory, Fundamental attribution error and naïve realism. Spontaneous trait inference is not synonymous with spontaneous trait transference, which is the phenomena where an individual is attributed a trait that they describe as being in someone else.[10]

History and concept origin

[edit]

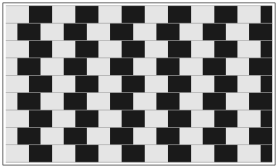

Unconscious inference[4] was the term first put forward by Hermann von Helmholtz, a German physicist and philosopher, in effort to define the phenomena which occurs when humans visually process certain qualities pertaining to people and, in particular, objects.[6] Helmholtz found that people unknowingly extrapolate data from visually processed information. He articulated this reflexive mechanism as the way in which people form impressions, through his exploration in the field of optical illusions. He posited that unconscious inference is the cause for people being able to be fooled by optical illusions.[6] The example commonly used to explain unconscious inference is that when a person visually perceives a sunset, they make the inference that the sun is moving below the horizon, but in reality, the sun is completely stationary and it is the earth which is moving.[6] Later on, in his research, Helmholtz related his concept of unconscious inference to psychology. In the third volume of "The Treatise on Physiological Optics", he explores the impact that visual perception has on the psychology of an individual.[6]

Though Helmholtz’ research and postulations were initially dismissed by psychologists. Largely due to the fact that his unconscious inference theory posed a fundamental error in logical reasoning. Edwin G. Boring explored this error, stating that the act of inferring is a conscious process, and in turn, can not be considered unconscious.[5] It has also been critiqued that Helmholtz’ studies and research on the subject hasn't effectively or significantly influenced the area of social psychology.[5]

However, the idea has since been revitalised by modern research. The theory that visual impressions trigger an instinctual reflex of inference, has been reshaped and refined to apply also to social psychology and human interaction. Its adoption into the psychology vernacular has been though, under alternate names such as snap judgments,[11] unintended thought,[2] but the most universally used is spontaneous trait inference.[12] This adaptation of Helmholtz’ unconscious inference describes the human tendency to allocate traits or qualities to individuals based on certain behaviours they observe the individual exhibiting. This allocation occurs spontaneously and is often a subconscious process, hence it is known as spontaneous trait inference.[5] The result of spontaneous trait inference is that a person unknowingly constructs a perception of an individual within their mind, based on the inferences made through behaviour observation. This perception contributes to the overall impression the individual will have on the person, and in turn contribute to the person's overall behaviour to the individual.[2]

Examples

[edit]Helmholtz’ examples

[edit]Helmholtz’ first example was that of how sunsets are perceived. When an individual witnesses the sun setting, they acknowledge it as if it were the sun moving to be hidden by the earth's horizon. This inference has been, and still continues to be made, despite the fact that the individual understands and knows that the sun is a stationary body, and it is the earth that is in motion. This example shows that the mental mechanism that comes to this conclusion has an enormous influence upon the impressions and perceptions of the individual, even overcoming factual knowledge.[6]

The second example that Helmholtz uses to express his theory of unconscious inference is that of a theatre performance. When an actor is on stage portraying a certain character with conviction, such that they are able to deliver a convincing and realistic performance; they are able to sway the emotions of the audience, evoking laughter, sadness, anger etc. within their audience. This is able to be done, despite the fact that all the audience members have the programme in hand which discloses to them the fact that the character on stage is merely an actor, and that all that is being portrayed is not real. Helmholtz posited that it was due to unconscious inference, the impression that the audience have of the actor allow them to be emotionally swayed.[6]

Social psychology examples

[edit]“Lily is, for instance, entertaining ladies and I come in with my filthy plaster cast, in sweat socks; I am wearing a red velvet dressing gown which I bought at Sulka’s in Paris in a mood of celebration when Frances said she wanted a divorce. In addition I have on a red wool hunting cap. And I wipe my nose and mustache on my fingers and then shake hands with the guests, saying “I’m Mr Henderson, how do you do?” And I go to Lily and shake her hand, too, as if she were merely another lady guest, a stranger like the rest. And I say, “How do you do?” I imagine the ladies are telling themselves, “He doesn’t know her. In his mind he’s still married to the first. Isn’t that awful” This imaginary fidelity thrills them.” – Saul Bellow, Henderson the Rain King (1958, p. 9)[13]

This extract from Saul Bellow's novel “Henderson the Rain King”,[13] portrays a common display of spontaneous trait inference. Here the character Mr. Henderson believes that the ladies, which he is introducing himself to, would be excited by his “fidelity” to his first wife. As he is reintroducing himself to his current wife, Lily, and in turn they would assume that “he doesn’t know her”. Showing that through the behaviour of reintroducing himself to his wife, the ladies would infer that he still believes he is married to his first wife. However, Mr. Henderson also displays spontaneous trait inference through his assumption that that is what the ladies will think. As Mr. Henderson has made the inference that the ladies would be presumptuous.[2]

Measurement

[edit]Numerous methods have been developed and utilised by researchers to investigate the prevalence and effect of spontaneous trait inference in an experimental context. These paradigms provide a construct through which spontaneous trait inference can be tested. The most prevalent paradigms utilised in research include the cued recall task, the picture priming task, and the word fragment completion task.[1][7]

For the cued recall task, an individual would be presented with written accounts of different behaviours, such as “Brittany fell over when she walked down the hill”. Later on, the experimenter would provide the individual with a cue, and utilising the cue as a prompt, the individual was asked to recall the behaviours that they had read earlier.[7] The cues formed the independent variable of the experiment, as the experimenter would change them in order to observe if there was a change in response.[1] It was found that characteristic words that described inferences extrapolated from the behaviour read, such as “clumsy”, presented as better cues for memory retrieval than actual words that appeared in the description itself.[1] This implies that not only were trait inferences spontaneously made, but they also established a lasting impression on the individual, such that the individual formed strong cognitive links between the behaviour and the trait.[1][7]

For the picture priming task, individuals were presented with an image or video, and then would have to identify a characteristic word that is initially hidden behind a black image and then gradually revealed over a 5-second period of time, by removing pieces of the black image at random.[1][7] It is the speed at which the individual is able to identify the word which is being tested. As when the characteristic word that is being identified is similar to inferences made from the image or video previously presented, the identification speed increases when compared to cases where the characteristic word that is being identified doesn't link to possible inferences made.[1] This shows that due to the implicit inferences made when viewing the stimuli, formed cognitive cues which prompted quicker identification.[1][7]

For the word fragment completion task, there are two groups of individuals which are asked to complete a word which has blanked letters.[1][7] The difference between the two groups is that, just prior to being given the word completion task, one group of individuals were presented with accounts of different behaviours, whilst the other group weren't presented with anything.[1][7] This method relies on the notion that the description of the behaviour would generate a trait inference, which would in turn aid with the completion of the fragmented word.[1] For example, an individual exposed to the description of “Brittany fell over when she walked down the hill”, would be able to produce the word clumsy from “c_ _ m _ y”, faster than an individual who wasn't primed with the description. The results showed this effect, in turn suggesting that the concept had already been implicitly formed by the individual when they were presented with the behaviour description.[1]

Applications

[edit]On social media

[edit]With the modern-day prevalence of social media, social psychologists have taken interest in the application of spontaneous trait inference within these contexts. As with the conditions surrounding social media, being very different to conditions of physical interaction, the question of whether spontaneous trait inference can still be applied arises.[9] Research has been conducted in order to investigate the occurrence of spontaneous trait inferences in circumstances typical of social media. These circumstances involved moderate, self-tailored content, multiple cues displayed simultaneously, with the speed of browsing dependent on the individuals own pace.[9] It was found that, without instruction to do so, individuals participating in the task had formed impressions and inferences of people based on social media information.[9] Research concluded that whilst scrolling through different social media platforms, the social media user extrapolates information from the content provided, and these inferences then implicitly inform the perception of the user.[9]

In culture

[edit]Research has been conducted in the area of cognitive mind-sets which promote the inclination to spontaneously infer traits based on behaviour. Through investigation it has been found that the cultural group, of which the individual is a part of, informs the types of inferences made by the individual.[8] Thus, being raised in a collectivist culture, which is generally the framework of Eastern societies, influences the types of inferences made by an individual differently, then if they were raised in an individualist culture, which is generally the framework of Western societies.[1] As individuals raised in collectivist cultures form an interdependent model of self and individuals raised in individualist cultures form an independent model of self. It was found that those who were raised in individualist cultures were not only more likely to form spontaneous trait inferences than those raised in collectivist cultures, but they also formed inferences that attributed behaviours witnessed to dispositional factors rather than accounting for situational factors.[8] Inferences made by those raised in collectivist cultures placed more weigh on the effect of situational factors on an individual's behaviour, than immediately attributing the individual's behaviour to their personality.[8]

Implications

[edit]Spontaneous trait inference has numerous implications in theoretical and practical instances. The quick and insubstantial conclusions formulated when observing an individual, leads to the formation of an inaccurate mental representation of that individual.[1] The representations humans form of each other, determines how they interact with each other. If that representation is formulated from inaccurate inferences, then the interaction between people will, in turn, be affected. This result then has the potential to cause serious conflicts, lead to further erroneous judgements, and result in rash decision making.[1] It can impact and influence a range of areas in society, ranging from social gatherings to decisions made in a legal setting. It can also contribute to the formation and perpetuation of social and cultural stereotypes.[1]

Through the understanding of spontaneous trait inference the interpretation models for other psychological phenomena are founded and further advanced. For example, Fundamental attribution error, which is the instinctive tendency to ascribe a certain behaviour to the individual's personality whilst neglecting the influence of situational factors, is a central concept to social psychology and is heavily founded on the spontaneous trait inference.[1][7] Another concept that is derived from the effect of spontaneous trait inference is belief perseverance effect, which is that individuals are more likely to retain their beliefs than change them when exposed to contradictory information.[1] Due to the fact that it provides a framework for the reasoning of other observable phenomena, spontaneous trait inference has a multitude of implications in the area of social psychology.

See also

[edit]- Attribution theory

- Fundamental attribution error

- Belief perseverance

- Naïve realism

- Zero-acquaintance personality judgments

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Fiedler K (2007). "Spontaneous Trait Inferences". Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. SAGE Publications, Inc. doi:10.4135/9781412956253.n552. ISBN 9781412916707.

- ^ a b c d e Uleman JS, Bargh JA (1989-07-14). Unintended Thought. Guilford Press. ISBN 9780898623796.

- ^ a b Uleman JS, Hon A, Roman RJ, Moskowitz GB (1996-04-01). "On-Line Evidence for Spontaneous Trait Inferences at Encoding". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 22 (4): 377–394. doi:10.1177/0146167296224005. S2CID 146436128.

- ^ a b Boring, Edwin G. (1929). A History Of Experimental Psychology. New York: Century.

- ^ a b c d e Boring EG (1949). Sensation And Perception In The History Of Experimental Psychology. New York: Century.

- ^ a b c d e f g Peddie W (July 1925). "Helmholtz's Treatise on Physiological Optics". Nature. 116 (2907): 88–89. doi:10.1038/116088a0. S2CID 4093480.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Uleman JS, Newman LS, Moskowitz GB (1996), "People as Flexible Interpreters: Evidence and Issues from Spontaneous Trait Inference", Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Elsevier, pp. 211–279, doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60239-7, ISBN 9780120152285

- ^ a b c d Na J, Kitayama S (August 2011). "Spontaneous trait inference is culture-specific: behavioral and neural evidence". Psychological Science. 22 (8): 1025–32. doi:10.1177/0956797611414727. PMID 21737573. S2CID 33675904.

- ^ a b c d e Levordashka A, Utz S (January 2017). "Spontaneous Trait Inferences on Social Media". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 8 (1): 93–101. doi:10.1177/1948550616663803. PMC 5221722. PMID 28123646.

- ^ Skowronski JJ, Carlston DE, Mae L, Crawford MT (April 1998). "Spontaneous trait transference: communicators taken on the qualities they describe in others". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 74 (4): 837–48. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.4.837. PMID 9569648.

- ^ Matson JR (August 1946). "Notes on Dormancy in the Black Bear". Journal of Mammalogy. 27 (3): 203–212. doi:10.2307/1375427. ISSN 0022-2372. JSTOR 1375427.

- ^ Newman LS, Uleman JS (1990-06-01). "Assimilation and Contrast Effects in Spontaneous Trait Inference". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 16 (2): 224–240. doi:10.1177/0146167290162004. S2CID 143051359.

- ^ a b Bellow S (1959). Henderson the Rain King. Viking Press. p. 9.