Soul City, North Carolina

Soul City, North Carolina | |

|---|---|

Soul City sign at the entrance to Green Duke Village | |

| Coordinates: 36°24′31″N 78°16′13″W / 36.40861°N 78.27028°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Warren County |

| Established | 1969 |

| ZIP code | 27563 |

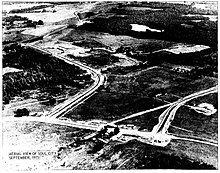

Soul City is a community in Warren County, North Carolina, United States. It was a planned community first proposed in 1969 by Floyd McKissick,[1] a civil rights leader and director of the Congress of Racial Equality. Funded by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, Soul City was one of thirteen model city projects under the Urban Growth and New Community Development Act. It was located on 5,000 acres (20 km2) in Warren County near Manson-Axtell Road and Soul City Boulevard in Norlina.[2][page needed]

Background

[edit]After the 1968 Civil Rights bill was passed, many civil rights activists focused on the economic development in black communities so African Americans could take advantage of the resources they had recently won.[3] Following his departure from CORE, McKissick founded McKissick Enterprises in August 1968, a company which was supposed to "create and distribute profits to millions of black Americans" by investing in and providing technical advice to black-run businesses.[4] It invested in a variety of projects.[5] Following the promulgation of the New Communities Act, McKissick tasked his staff with drafting a plan for a new city in the South,[6] figuring that new planned community there would attract more interest if it was located there rather than elsewhere.[7]

Wanting to improve conditions in his home state and feeling that it was more politically and economically progressive than its other Southern contemporaries, McKissick settled on locating the community in North Carolina.[8] He tasked former legal colleague T. T. Clayton with discreetly searching for potential sites.[9] After rejecting a property in Halifax County as too small for his ambitions, McKissick took interest in a 1,800 site in Warren County. Named the Circle P Ranch, the land was a cattle and timber farm owned by Leon Perry, who was losing money and eager to sell.[10] Once a tobacco plantation, it contained woods, pastures, creeks, old agricultural buildings, centered around a historic manor house.[11]

Warren County was a majority black rural area facing economic downturn.[12][13] It was the third poorest county in the state and was experiencing the largest population decline in the state.[14] Educational attainment rates were low.[15] Services and utilities in the area near the ranch were minimal. The house was serviced by electricity and the site had several wells and septic tanks, but there was no centralized water or sewage access and only one proximate paved road.[16] Despite these problems, McKissick felt optimistic about the property's potential owing to low regional labor costs—which were beneficial to attracting industry, its geographic centrality relative to major urban centers within 500 miles, and its proximity to U.S. Route 1 and the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad. There were also adjacent tracts amounting to—in Clayton's estimation—5,000 acres which could be further acquired.[17] Kerr Lake, several miles away, was well placed to serve as a reservoir for a city.[18] He also felt that establishing a planned community to help blacks on a former plantation once owned a by a segregationist legislator would have symbolic resonance.[19]

Clayton negotiated with Perry to purchase the land for $390,000. On December 19, 1968, Clayton paid Perry $4,000 for a 60-day option to purchase his ranch. Clayton and McKissick, with Perry's assent, subsequently assigned the option interest to McKissick Enterprises.[19] On January 13, McKissick held a joint press conference with U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman to announce his intent to build a planned community called "Soul City" in Warren County.[20][21][a] McKissick argued that the project would help ameliorate issues of black outmigration from the South and urban decay in major American cities by "helping to put new life into a depressed area" and "helping to stem the flood of migrants to the already over-crowded and decaying cities".[24] While insisting that Soul City would "be open to residents of all colors", he emphasized that the town would generate "new careers for black people" and that it would "be an attempt to move into the future, a future where black people welcome white people as equals".[24]

McKissick's announcement generated a significant amount of media attention, with the Big Three television networks each covering it on their evening news programs and The Washington Post reporting on it in a front page story.[25] Some outlets, such as The News & Observer and The Charlotte Observer, expressed skepticism at the economic viability of the project, while others such as the Greensboro Daily News and journalist Claude Sitton feared that it would manifest itself as an experiment in black separatism and clash with the integrationist goals of the civil rights movement.[26] McKissick, though continuing to emphasize the role blacks would play in the project, was incensed by the characterization of his project as separatist, telling one newspaper, "This is neither integration nor segregation, but letting black people do what ever they damn please, and go where they please."[27] Some progressives, such as Elizabeth Tornquist of the North Carolina Anvil, attacked the plan for relying too much on capitalism, which they considered exploitative and predisposed to enrich the project's leaders while unlikely to provide any long term benefit to poor blacks.[28] Response from black newspapers was generally optimistic, and McKissick received some favorable correspondence from blacks around the country.[29] Several black leaders and activists expressed skepticism at the proposal, such as National Urban League director Whitney Young.[30] Reactions in Warren County were mixed, with many locals surprised by McKissick's announcement.[31][32] Perry received death threats for offering the sale to McKissick and briefly fled to Florida.[33]

Establishment and planning

[edit]In the weeks following his press conference, McKissick retained architecture firm Ifill Johnson Hanchard to design Soul City and a consulting firm to provide economic analysis. He focused most of his efforts on securing the financing necessary to purchase Perry's ranch.[34] After making unsuccessful entreaties to several institutions, he met with executives of Chase Bank and asked them to lend him $390,000. They eventually agreed to loan him $200,000 out of an affiliated bank in Lumberton.[35] Unable to secure an additional bank loan, McKissick agreed to purchase the land with a loan from Perry for the remainder of the balance with the promise that he would pay it off within a year. He officially received the deed for the property on February 21, 1969.[36] Securing some additional funding from Rhode Island businessman Irving Fain, McKissick then reluctantly sought out grants from the federal government.[37] A few months later the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development granted $243,000 to the state of North Carolina which, with the quiet support of Governor Bob Scott, forwarded over half of the money to McKissick's newly-established Warren Regional Planning Corporation. Chase Bank also extended McKissick $200,000 in additional credit.[38]

Confronted with Ifill Johnson Hanchard's lack of expertise in urban planning, McKissick hired architect Harvey Gantt to plan Soul City. Heavily influenced by the layout of Columbia, Maryland, Gantt envisioned Soul City to be a collection of villages oriented around a core area which would include amenities such as a mall, a hospital, a college, and a central library.[39] Each village was to have unique aesthetics but all were to include residential structures of mixed density centered around their own "activity center", which would include basic social and commercial amenities. North of the town core and proximate to the railway and the highway was to be an 800-acre industrial park. Between the park and the town center there would be a man-made lake which would provide water for firefighting protection.[40] A boulevard running north-to-south through the middle of the community and a ring road passing through the villages would serve as the major transportation arteries. Sidewalks were to be wide and bike paths were to link the villages together.[41] For recreation and to preserve the community's rustic setting, Gantt planned for five community parks, one central park, and several dozen playgrounds and picnic areas. One third of the land in the community was to remain undeveloped natural area.[42] Gantt devoted little time to the design of individual structures, but in his early draft depicted 1970s contemporary styles which included modular and sleek styles with minimal ornamentation and the use of glass, brick, and concrete.[43]

McKissick was keen to develop a community with a healthy social atmosphere and cohesive culture.[43] To that end, he created the Soul City Foundation, a non-profit organization led by Eva Clayton, to develop social life in the community.[44] McKissick reach an agreement with Warren County officials to work to find funding for the construction of a school which the county could operate for local children until its student body was of sufficient size to be self-sustaining at which point its control would be relinquished to the community.[45] After studying different models for public governance, McKissick decided to petition the Warren County Board of Commissions and the North Carolina Board of Health to create a Soul City Sanitary District, which would collect taxes and fund the provision of water, sewer, waste collection, and firefighting services.[46]

Development

[edit]In late 1969, McKissick purchased four residential trailers and one office trailer and moved them to the Circle P. Ranch. Over the following weeks the trailers were occupied by McKissick's staff and their families.[47] Over the following months the staff focused on cleaning out a barn for use as an office and the Green Duke House for use as a community center.[48] McKissick remained in New York but visited every few weeks with his wife and sometimes some of his children.[49] He and his wife moved to the community in mid-1971.[50]

Goals and plans

[edit]Soul City was intended to be a new town built from the ground up and open to all races, while placing an emphasis on providing opportunities for minorities and the poor.[1][51] It was also designed to be a means of reversing out-migration of minorities and the poor to urban areas; the opportunities Soul City provided, such as jobs, education, housing, training, and other social services would help lessen the migration.[52]

The city was planned to contain three villages housing 18,000 people by 1989. Soul City was projected to have 24,000 jobs and 44,000 inhabitants by 2004.[52] It was intended to include industry and retail development for jobs, as well as residential housing and services. The plan was for residents to work, get schooling, shop, receive health care, and worship in town. Soul City was the first new town to be organized by African-American businesses. McKissick envisioned Soul City as a community where all races could live in harmony.[53]

Federal funding and political opposition

[edit]McKissick believed the way to improve the economic situation of African Americans at that time was through black capitalism. He said, "Unless the Black Man attains economic independence, any political independence will be an illusion.[54] Richard Nixon supported Black capitalism, and McKissick backed Nixon in his 1972 re-election in efforts to get more funding from HUD.[54] In 1972, the city received a grant of $14 million from HUD based on plans of attracting industry as well as developing residential housing and by the late 1970s, the city had received more than $19 million federal funds with an additional $8 million from state and local sources.[3]

The U.S. Senator Jesse Helms, repeatedly attacked the project as a boondoggle and a waste of taxpayer money. A series of articles in the Raleigh News & Observer falsely accused McKissick of fraud and corruption and a congressional audit of the development stalled progress for nine months, only to clear Soul City of the charges leveled against it.[55][56]

Rise and decline

[edit]By 1974, pioneering families moved to Soul City and steady progress was apparent in the laying of water and sewer lines, construction of roads, a day care center, a health care center, and early construction of "Soul Tech I" (with 52,000 square feet of industrial space).[57] In 1977, the community lake was completed.[58]

Soul City's decline was caused by several factors, such as the local economy of Warren County, the national economy, and negative press coverage. Warren County had over 40% of people not graduating high school. The shortage of skilled laborers and lack of industrial experience deterred some industries from moving to Soul City. The US economy had a major downturn in 1974 as inflation hit double digits in 1973 and 1974. For the rest of the decade, the country went through "stagflation", "the simultaneous burden of inflation and unemployment."[3] The state of the national economy made many industrial companies cautious of expanding. The Soul City Company (SCC) reported that CC Grander, a utility company and Burlington Industries, a textile company both had plans to move to Soul City but halted their expansion during the economic uncertainty of the country.[3] The HUD's new town programs were signed and launched during the country's economic downturn. Some argue that Soul City as well as other new town programs would have succeeded if there had not been an economic recession. Michael Spear, the former general manager of the new town of Columbia, Maryland, commented that "launching a new towns program in the early 1970s was like asking the Wright brothers to test their airplane in a hurricane and then concluding, when it crashed, that the invention did not work."[3]

The negative press coverage of some media companies deterred not just industries but also white homeowners. The press covered Soul City as a "new black town", which made it unappealing for white residents to move in. The Wall Street Journal, which had significant credence in the business community, negatively portrayed McKissick as a lawyer with a lavish lifestyle. The Journal damaged McKissick's name and identity, which negatively impacted his efforts in bringing in new industry. The city failed to reach its initial ambitions. Lawsuits and investigations into the use of funds by the Soul City Company, the city's developers, resulted in foreclosure in 1979 despite eventually being cleared by a Government Accountability Office audit.[59]

HUD pulled its funding for Soul City in 1979. McKissick remained living in Soul City until his death in 1991. He was buried on his family's property.[60]

Post-HUD history

[edit]

In the mid-1980s a sportswear company opened a sewing operation in Soul Tech I. The population of Soul City grew to about 300,[61] and later in the decade an affordable housing complex was built in the Green Duke Village.[62] Several additional single-family houses were also constructed, mostly at the behest of retirees.[60] In 1989, some investors purchased 100 acres of Soul City land to develop into an industrial park, but their plans never came to fruition after failing to attract industry. In 1994, North Carolina announced the construction of medium-security prison in Soul City. The reception from locals was mixed, with some opposed to the project and others feeling it would create jobs. The Warren Correctional Institution was completed in 1997. Several years later state prison officials purchased Soul Tech I and converted it into a prison factory for producing janitorial supplies.[61]

Population decline in the late 1980s and 1990s led to decreasing revenue for homeowners' association responsible for the management of Green Duke Village. As a result, the physician infrastructure of Soul City degraded and Warren County government assumed control of the Magnolia Ernest Recreation Complex and opened it to the public.[63] In the mid-2000s the land on which the Soul City monolith was located was sold and the new owner indicated her intention to demolish it. After a public outcry from local residents, county officials moved the sign to the entrance of Green Duke Village. In 2009, HealthCo closed due to an inquiry into its finances.[62]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This marked the first time McKissick publicly used the name "Soul City".[22] The origins of the name are unclear. One account holds that various staffers involved in the project dubbed the name from the perception that a new city needed "soul". Civil rights activist Gordon Carey believed that McKissick chose the name. McKissick later claimed the name was chosen for a religious allusion, and not to evoke black culture, the connotation which it would quickly assume.[23] Soul City staffers referred to the project initially as "Black City" and later as "New City".[22]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "North Carolina History Project : Soul City". Northcarolinahistory.org. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ Healy 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Minchin 2005.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 61, 70.

- ^ Healy 2021, p. 63.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Healy 2021, p. 81.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 86, 88–89.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 88–90.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 87–88, 90.

- ^ Minchin 2005, p. 132.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Strain 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Healy 2021, p. 90.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 89, 91–92.

- ^ Strain 2004, pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b Healy 2021, p. 93.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Strain 2004, p. 57.

- ^ a b Healy 2021, p. 172.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 171–172.

- ^ a b Healy 2021, p. 96.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 97–98, 100–101.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Healy 2021, p. 103.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 105–107.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 110–114.

- ^ Strain 2004, p. 62.

- ^ Healy 2021, p. 114.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 116–119.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Healy 2021, p. 146.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 147–148.

- ^ a b Healy 2021, p. 148.

- ^ Healy 2021, p. 149.

- ^ Healy 2021, p. 150.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Healy 2021, p. 159.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Healy 2021, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Schultz, Will. "Soul City." North Carolina History Project : North Carolina History, n.d. Web. 09 Mar. 2013.

- ^ a b McKissick, Floyd B. Soul City North Carolina. Soul City, NC, 1974. Print.

- ^ Bey, Lee (May 12, 2016). "Story of cities #41: Soul City's failed bid to build a black-run suburbia for America". The Guardian. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ a b Kelefah, Sanneh (February 1, 2021). "The Plan to Build a Capital for Black Capitalism". The New Yorker.

- ^ "The 1970s Black Utopian City That Became a Modern Ghost Town". The Atlantic. February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Soul City - North Carolina History". northcarolinahistory.org. Retrieved December 25, 2024.

- ^ Christopher Strain. 2004. "Soul City, North Carolina: Black Power, Utopia, and the African American Dream." Journal of African American History 89, no. 1 (Winter 2004), pages 57–74.

- ^ Healy 2021, p. 343.

- ^ "Information on the New Community of Soul City, North Carolina". www.gao.gov. December 18, 1975. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ a b "SOUL CITY: RUMORS OF ITS DEATH HAVE BEEN GREATLY EXAGGERATED". Greensboro News & Record. Associated Press. June 13, 1995. Retrieved December 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Healy 2021, p. 338.

- ^ a b Healy 2021, p. 341.

- ^ Healy 2021, p. 340.

Works cited

[edit]- Healy, Thomas (2021). Soul City: Race, Equality, and the Lost Dream of an American Utopia. New York City: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 9781627798624.

- Minchin, Timothy J. (2005). ""A Brand New Shining City": Floyd B. McKissick Sr. and the Struggle to Build Soul City, North Carolina". The North Carolina Historical Review. 82 (2): 125–155. ISSN 0029-2494. JSTOR 23523505.

- Strain, Christopher (2004). "Soul City, North Carolina: Black Power, Utopia, and the African American Dream". The Journal of African American History. 89 (1) (Winter ed.): 57–74. doi:10.2307/4134046. JSTOR 4134046.

External links

[edit]- Floyd B. McKissick. Soul City North Carolina, 1974 on Hathi Trust (14 pages).

- Amanda Shapiro. "Welcome to the Soul City." Oxford American, A Magazine of the South 80 (Spring 2013). online version from April 4, 2016.

- Soul City - A dream. Will it come true? Dan Hull, The Chronicle, Duke University, March 1, 1974

- Planned communities in the United States

- Utopian communities in the United States

- Populated places established in 1969

- Warren County, North Carolina

- 1969 establishments in North Carolina

- Unincorporated communities in North Carolina

- Unincorporated communities in Warren County, North Carolina

- Populated places in North Carolina established by African Americans