Reciprocity (social psychology)

In social psychology, reciprocity is a social norm of responding to an action executed by another person with a similar or equivalent action. This typically results in rewarding positive actions and punishing negative ones.[1] As a social construct, reciprocity means that in response to friendly actions, people are generally nicer and more cooperative. This construct is reinforced in society by fostering an expectation of mutual exchange. While the norm is not an innate quality in human beings, it is learned and cemented through repeated social interaction. Reciprocity may appear to contradict the predicted principles of self-interest. However, its prevalence in society allows it to play a key role in the decision-making process of self-interested and other-interested (or altruistic) individuals. This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as reciprocity bias, or the preference to reciprocate social actions.[2]

Reciprocal actions differ from altruistic actions in that reciprocal actions tend to follow from others' initial actions, or occur in anticipation of a reciprocal action, while altruism, an interest in the welfare of others over that of oneself, points to the unconditional act of social gift-giving without any hope or expectation of future positive responses.[3] Some distinguish between pure altruism (giving with no expectation of future reward) and reciprocal altruism (giving with limited expectation or the potential for expectation of future reward).[4] For more information on this idea, see altruism or altruism (ethics).

History

[edit]Reciprocity dates as far back as the time of Hammurabi (c. 1792–1750 BC). Hammurabi's code, a collection of 282 laws and standards, lists crimes and their various punishments, as well as guidelines for citizens' conduct.[5] The "eye for an eye" principles in which the laws were written mirror the idea of direct reciprocity. For example, if someone caused the death of another person, they too would be put to death.

Reciprocity was also a cornerstone of Ancient Greece. In Homeric Greece, citizens relied on reciprocity as a form of transaction as there was no formal system of government or trade.[6] In Homer's Iliad, he illustrates several instances of reciprocal transactions in the form of gift giving. For example, in Book VI of the Iliad, Glaucus and Diomedes exchange armor when they discover that their grandfathers were friends.[7] However, there were times when direct reciprocity was not possible, especially in times of great need when a citizen had nothing to give for repayment.[8] Thus, delayed reciprocity was also prevalent in Greek culture at this time. Delayed reciprocity refers to doing a positive action in service of another, including a gift or favor, with the understanding that they will repay this favor at another time when the initial giver is in great need.[9] This form of reciprocity was used extensively by travelers, particularly in the Odyssey. Odysseus often had to rely on the kindness of human strangers and other mythological creatures to secure resources along his journey.[10]

In the classical Greek polis, large-scale projects such as construction of temples, building of warships and financing of choruses were carried out as gifts from individual donors. In Rome, wealthy elite were linked with their dependents in a cycle of reciprocal gift giving.[11] As these examples suggest, reciprocity enjoyed a cultural prestige among ancient aristocracies for whom it was advantageous.[12] The institutionalization of reciprocity has its origins in ancient societies, but continues today in politics and popular culture. For more, see Reciprocity (social and political philosophy).

As an adaptive mechanism

[edit]Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin attribute the very nature of humans to reciprocity. They claim humans survived because our ancestors learned to share goods and services "in an honored network of obligation."[13] Thus, the idea that humans are indebted to repay gifts and favors is a unique aspect of human culture. Cultural anthropologists support this idea in what they call the "web of indebtedness" where reciprocity is viewed as an adaptive mechanism to enhance survival.[14] Within this approach, reciprocity creates an interdependent environment where labor is divided so that humans may be more efficient. For example, if one member of the group cares for the children while another member hunts for food for the group, each member has provided a service and received one in return. Each member can devote more time and attention to his or her allotted task and the whole group benefits. This meant that individuals could share resources without actually giving them away. Through the rule of reciprocity, sophisticated systems of aid and trade were possible, bringing immense benefits to the societies that utilized them.[15] Given the benefits of reciprocity at the societal level, it is not surprising that the norm has persisted and dictates our present cognition and behavior.

The power of reciprocity

[edit]Reciprocity is not only a strong determining factor of human behavior; it is a powerful method for gaining one's compliance with a request. The rule of reciprocity has the power to trigger feelings of indebtedness even when faced with an uninvited favor[16] irrespective of liking the person who executed the favor.[17]

Strength

[edit]In 1971, Dennis Regan tested the strength of these two aspects of reciprocity in a study entitled "Effects of a Favor and Liking on Compliance." In this experiment, participants believed they were in an art appreciation experiment with a partner, "Joe", who was actually a confederate. During the experiment, Joe would offer a soft drink to his co-participant. After the experiment was over, Joe would ask the participant to buy raffle tickets from him. The more the participants liked Joe, the more likely they were to buy raffle tickets from him. However, when Joe had given them a soda, which thus indebted them to reciprocate, the participants feelings toward Joe were no longer a significant predictor of purchasing tickets. The rule of reciprocity proved to be more salient in this decision-making process than did how much they liked a person.[17] Thus, individuals who we might not even like have the power to greatly increase our chances of doing them a favor simply by providing us with a small gift or favor prior to their request. Furthermore, we are obliged to receive these gifts and favors which reduces our ability to choose to whom we wish to be indebted.[15]

Politics is another area where the power of reciprocity is evident. While politicians often claim autonomy from the feelings of obligation associated with gifts and favors that influence everyone else, they are also susceptible. In the 2002 election, U.S. Congress Representatives who received the most money from special interest groups were over seven times more likely to vote in favor of the group that had contributed the most money to their campaigns.[15]

Automaticity

[edit]In 1976, Phillip Kunz demonstrated the automatic nature of reciprocity in his experiment, "Season's greetings: From my status to yours" using Christmas cards. In this experiment, Kunz sent out holiday cards with pictures of his family and a brief note to a group of complete strangers. While he anticipated some responses, holiday cards came pouring back to him from people who had never met nor heard of him and who expressed no desire to get to know him any better.[18] The majority of these individuals who responded never inquired into Kunz's identity, they were merely responding to his initial gesture with a reciprocal action.

Cooperation

[edit]Fehr & Gächter (2000) in "Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments" showed that, when acting within reciprocal frameworks, individuals are more likely to deviate from purely self-interested behavior than when acting in other social contexts. Participants were allotted an endowment of 20 monetary units (i.e. dollars). They were given the choice to anonymously donate how much of their endowment to contribute to a public good. All contributions from each participant was multiplied by a factor such as by 10, and then the multiplied sum was distributed equally, regardless of what share of the total an individual contributed. This experiment illustrates the free-rider problem, where an individual in a group benefits from the contributions of others, while simultaneously not contributing any of their own resources. The optimal outcome occurs when every participant contributes the maximum amount, allowing the highest amount of funds to be shared, while involving cooperation by all. Other conditions in this experiment included punishment conditions, where participants could penalize non-contributing actors. This experiment found that without punishments, contributions declined, demonstrating when and how free-riding occurs. Across punishment conditions, contributions were high and stayed relatively stable. Participants were willing to use some of their funds to punish non-contributors, indicating how important negative reciprocity can be in action.[19]

Reciprocity over self-interest

[edit]Magnanimity is often repaid with disproportionate amounts of kindness and cooperation, and treachery with disproportionate amounts of hostility and vengeance, significantly surpassing amounts determined or predicted by conventional economic models of rational self-interest. Moreover, reciprocal tendencies are frequently observed in situations wherein transaction costs associated with specific reciprocal actions are high and present or future material rewards are not expected. Whether self-interested or reciprocal action dominates the aggregate outcome is particularly dependent on context; in markets or market-like scenarios characterized by competitiveness and incomplete contracts, reciprocity tends to win out over self-interest.[20]

The Prisoner's Dilemma

[edit]

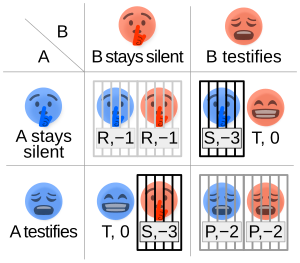

The Prisoner's Dilemma is a key example of reciprocity and self-interest in action. In this scenario, frequently visualized by a 2x2 grid, both A and B have committed the same crime, together. Their punishment for the crime is dependent on if they each confess or not, in relation to if the other actor confesses as well.

- [3 years, 3 years]: If both confess, they both receive a moderate sentence.

- [0 years, 5 years]: If A confesses and B stays silent, A receives no punishment, while Bob receives a severe sentence.

- [5 years, 0 years]: If A stays silent and B confesses, A receives a severe sentence, while B receives no punishment.

- [1 year, 1 year]: If both stay silent, they both receive a minor sentence.

The Dilemma

[edit]Individually, each prisoner is incentivized to confess, regardless of what the other does. This leads to a suboptimal outcome for both, where they both end up with a moderate sentence. However, if they both agree to stay silent, they both receive a minor sentence, a better outcome for both.

The Prisoner's Dilemma is a telling demonstration of reciprocity because each actor is incentivized to cooperate to ensure the best outcome for them both. The choice to testify can lead to the optimal outcome for one actor if the other actor does not testify, but since this cannot be guaranteed, it is regarded as a safer choice to choose to stay silent in the hopes that the other actor will make this choice as well. In continuous games of the Prisoner's Dilemma run by a computer, over time, the computer will defer to the strategy of cooperation, indicating how reciprocity is a choice reached after the player observes the other actor working in their favor. This is a significant illustration of the idea of 'tit-for-tat', where in payoff-based scenarios, individuals will commit to cooperative strategies if they stand to gain from them as well.[21]

Positive and negative reciprocity

[edit]Positive reciprocity occurs when an action committed by one individual that has a positive effect on someone else is returned with an action that has an approximately equal positive effect.[22][23] For example, if someone mows their neighbor's lawn, the person who received this favor should then return this action with another favor such as a small gift. However, the reciprocated action should be approximately equal to the first action in terms of positive value, otherwise this can result in an uncomfortable social situation.[24] If someone mows another person's lawn and that person returns the favor by buying that individual a car, the reciprocated gift is inappropriate because it does not equal the initial gesture, whereas returning the favor with something small but kind, like baking a cake, would be considered commensurate to the situation. Individuals expect actions to be reciprocated by actions that are approximately equal in value.[22] This value is often viewed to be context dependent; some actions' reciprocals may be based on financial value, while others may be based on time invested or effort required.[25]

One example of positive reciprocity is that waitresses who smile broadly or give small gifts to their patrons receive more tips than waitresses who present a minimal smile.[26][27] Also, free samples are not merely opportunities to taste a product but rather invitations to engage in the rule of reciprocity. Many people find it difficult to accept the free sample and walk away. Instead, they buy some of the product even when they did not find it that enjoyable.[15]

Negative reciprocity occurs when an action that has a negative effect on someone is returned with an action that has an approximately equal negative effect.[23][28] For example, if an individual commits a violent act against a person, it is expected that person would return with a similar act of violence. In more modern societies and structures of justice, this generally translates into legal action, jail time, and even the death penalty. If, however, the reaction to the initial negative action is not approximately equal in negative value, this violates the norm of reciprocity and what is prescribed as allowable.[24] Retaliation, or revenge, actions taken against a person or group to induce harm in response to a previous grievance is an example of negative reciprocity. This definition of negative reciprocity is distinct from the way negative reciprocity is defined in other domains. In cultural anthropology, negative reciprocity refers to an attempt to get something for nothing.[29] It is often referred to as "bartering" or "haggling" (see reciprocity (cultural anthropology) for more information).

Reciprocal concessions

[edit]There are more subtle ways of initiating the reciprocity rule than merely doing something nice for someone so you may expect something in return. One instance of this more subtle form of reciprocity is the idea of reciprocal concessions. In a reciprocal concession, the requester initially makes a larger request, then a smaller request that is more feasible, making the respondent more likely to agree to a second request.

Under the rule of reciprocity, we are obligated to concede to someone who has made a concession to us.[30] That is, if an individual starts off by requesting something large and you refuse, you feel obligated to consent to their smaller request even though you might not be interested in either of the things they are offering. Robert Cialdini illustrates an example of this phenomenon by telling a story of a boy who asks him to buy five-dollar circus tickets and, when Cialdini refuses, asks him to buy some one dollar chocolate bars. Cialdini feels obligated to return the favor and consents to buying some of the chocolate bars.[30]

The rule of reciprocity operates in reciprocal concessions in two ways: pressure and expectation.

- First, an individual is pressured to reciprocate one concession for another by nature of the rule itself.

- Second, because the individual who initially concedes can expect to have the other person concede in return, this person is free to make the concession in the first place. If there were no social pressure to return the concession, an individual runs the risk of giving up something and getting nothing in return.

Effectiveness

[edit]- Psychological Obligation: Concessions create a perception of goodwill, which the other party feels obligated to match.[31]

- Norm of Cooperation: People tend to align with cooperative norms when they observe the other person acting in good faith.[32]

- Contrast Effect: The smaller request appears more reasonable when compared to the larger one.[33]

Mutual concession is a procedure that can promote compromise in a group so that individuals can refocus their efforts toward achieving a common goal. Reciprocal concessions promote compromise in a group so that the initial and incompatible desires of individuals can be set aside for the benefit of social cooperation.[30]

The door-in-the-face technique

[edit]The door-in-the-face technique, otherwise known as the rejection-then-retreat technique, involves making an outrageous request that someone will almost certainly turn down, and then making a smaller request that was the true item of interest all along. If executed successfully, the second request is seen as a concession so compliance with the second request is obtained.[30][34][35] However, one must proceed with caution when using this technique. If the first request is so big that it is seen as unreasonable, the door in the face technique proves useless as the concession made after may not be perceived as genuine.[36] The door in the face technique is not to be confused with the foot-in-the-door technique where individuals attempting to get a person to agree with a large request by first getting them to agree to a small or moderate request.[37]

Influence: Science and Practice

[edit]The book Influence: Science and Practice by Robert Cialdini is a prominent work in the field of reciprocity and social psychology. First published in 1984, the work outlines the main principles of influence, and how they can be applied in one's life to succeed, especially in business endeavors.[38] People use heuristics or general strategies, to make decisions more easily in a complex and stimulating world, and these strategies can be embraced to help oneself influence others.[39]

The seven principles are:

- Reciprocation

- Commitment and consistency

- Social proof

- Liking

- Authority

- Scarcity

- Unity

For more on Influence, see Influence: Science and Practice.

Reciprocity in the workplace

[edit]Social reciprocity holds significant importance in the workplace as it contributes to the foundation for effective collaboration, teamwork, and a positive work environment. The principle of reciprocity fosters a sense of trust[40] and interdependence among employees, which enhances overall workplace dynamics. When employees reciprocate positive actions, such as providing support, sharing information, or acknowledging achievements, it contributes to a culture of mutual respect and cooperation.

Practicing social reciprocity in the workplace can strengthen interpersonal relationships, recognized as a social norm within employees of the same status.[41] Meanwhile, failed reciprocity at work has the potential to lead to negative emotions and heightened stress.[42] By experiencing a continued lack of reciprocity, the perceived positive work culture may erode, causing negative associations to form with the workplace and one's coworkers. Failed reciprocity, a lack of an equivalent favor in return for a positive action, in the workplace has the potential to diminish trust, weaken social support, and can even increase the probability of suffering from stress-related diseases.[42] In attempting to improve the quality of a work environment, it is crucial to acknowledge and encourage efforts of reciprocity within the employees.

Negative reciprocity in the workplace

[edit]Harmful behavior also tends to be reciprocated with harmful behavior.[43] A meta-analysis by Greco et al. (2019) analyzed negative workplace behaviors ranging from bullying and harassment to counterproductive work behavior.

Study Design

They separated them into different categories according to severity (minor, moderate, severe), activity type: if the action was the result of withholding a positive behavior, refusing to act, or the execution of a negative behavior (passive, balanced, active), and target (whether the behavior was reciprocated or displaced to another person).[43]

Results

The analysis found that negative behaviors tend to be reciprocated with the same kind of behavior and the strongest relationship was found in reciprocity using a matched level of severity and activity; however, negative workplace behaviors that escalate in severity or activity also showed a strong and positive relationship.[43] Moreover, when the frequency of negative workplace behaviors increases this is generally reciprocated, with the other person also increasing the frequency of their negative behaviors.[43] The weakest effect was found to be de-escalation in activity or severity, which means that most people tended to respond with the same or a greater amount of reciprocity in negative workplace behaviors, rather than responding with a more mild action.[43]

De-escalation

In the category of severity, de-escalation only took place when Party A engaged in severe behaviors like violence or harassment, while Party B engaged in moderately severe behavior. This discrepancy may have been a result of abiding by ethical norms and avoiding legal repercussions as a consequence of their behavior.[43] Many of the articles analyzed did not include the target of the negative behaviors, limiting the breadth of information on this category.[43] However, they found that for two cases of de-escalation, the reciprocated negative behavior was directed at the instigator instead of being displaced.[43] There was also one case of escalation in which the reciprocated behavior was targeting the instigator.[43]

A news article summarizing similar research studies suggests that negative reciprocity might exist in order to restore or build a cooperative relationship.[44] They stated that the strategy treats balance as a goal, especially because it involves a relatively proportional response to harm.[44]

Reciprocity and trust

[edit]Trust in reciprocity takes into consideration three different factors: the individual’s risk preferences (whether or not the person has a tendency to accept risks in trust decisions), their social preferences (whether the individual shows prosocial tendencies or betrayal aversion), and lastly, their beliefs about the other’s trustworthiness (includes social priors like implicit racial attitudes and the reputation of the other individual based on previous experiences.[45]

A coordinated meta-analysis of 30 fMRI studies concluded that trust in reciprocity might cause an adverse feeling at the beginning of a series of interactions with a stranger. This is likely due to the inherent uncertainty of a decision outcome, leading individuals to be unsure about whether the other person will reciprocate their actions.[45] However, as interpersonal trust grows people are more confident and willing to cooperate with their partners.[45] Interpersonal trust builds up through a learning mechanism that takes information from previous interactions in which the other individual cooperated or did not cooperate.[45] This learning mechanism helps the individual label the other person as trustworthy or untrustworthy.[45] This meta-analysis also found that reciprocity, trust, and feedback learning show activity in different areas of the brain, which suggests that all of them are part of different cognitive processes.[45]

This theme of reciprocity and trust is also discussed in science magazines such as the Greater Good Magazine where the writers mention that people are more likely to be cooperative with others who act cooperatively towards them or have a reputation of being cooperative.[46]

Self-serving reciprocity

[edit]Reciprocity has been previously documented as automatic because it requires less cognitive control than other self-serving behaviors.[47] The researchers of a series of experiments around this topic wanted to investigate whether this automatic reciprocity was motivated by true fairness or whether it is a result of wanting to appear like a fair person.[47] To test this they used a two-player activity called the "Trust Game" or the "Investment Game."[47] Participants were given a determined amount of chips/money. The sender is supposed to decide the amount of money/chips (all, some, none) they want to transfer to the trustee or whether they want to keep the money/chips for themselves.[47] The experimenter multiplies the amount transferred from the sender and gives it to the trustee. The trustee then decides whether or not to transfer (all, some, none) back.[47]

Experimental Design

[edit]This series of experiments contained a condition where the trustees are informed that their chips are worth twice as much as the sender’s chips, which gives them the option to appear fair (while in reality, not being fair) and another option to be genuinely fair.[47] They also divided the groups manipulating the participant’s cognitive control.[47]

Cognitive Control

- Cognitive control allows individuals to consider options and factors, suppress personal impulses, and make decisions aligned with norms such as fairness rather than defaulting to their own self-interest.[47]

- Manipulations

- Ego Depletion: Participants were made to feel mentally fatigued by performing tasks that require sustained self-control, thus reducing their ability to exert cognitive control in subsequent tasks.[47]

- Time Constraints: Participants were placed under strict time limits, which forced them to rely on quick, automatic responses rather than deliberation.[47]

Findings

When cognitive control was diminished (due to ego depletion or time pressure), participants were more likely to default to self-serving reciprocity—behaviors that appeared fair on the surface but that in reality, were driven by self-interest. Under conditions of full cognitive control, participants were better able to align their actions with genuine fairness norms, rather than simply maintaining the appearance of fairness.[47] Researchers found that people tend to turn to reciprocal behavior when there is a lack of cognitive control.[47] When participants had limited cognitive control, they used the extra information to positively reciprocate to a lesser extent than people without the cognitive control manipulation. However, even with reduced cognitive control, they chose to benefit from the exchange if the outward perception of their behavior would look fair and reciprocal. This demonstrated that their main goal was to appear fair, not to behave in a fair manner.[47] A news article summarized a research study that supports these findings in which researchers found that people tend to take more time to make a generous choice than to make a selfish one.[48]

Reciprocity in conversation analysis

[edit]Conversation analysis, a methodology used to study how shared understanding is reached in naturally occurring conversation, employs the principle of reciprocity to explain how certain phenomena occur in conversation. Reciprocity occurs in conversational activities and practices such as:

- Turn-Taking:

- Reciprocity is present in the mechanism of turn-taking, where participants coordinate the exchange of speaking turns.[49] When one speaker asks a question, the recipient typically provides an answer, which reflects reciprocity in verbal engagement.

- Sequential Organization:

- Conversations are organized in sequences, such as adjacency pairs (e.g., question-answer, greeting-response). Reciprocity ensures that one part of the pair (e.g., a question) creates an expectation for a corresponding response (for example, an answer).[49]

- Repair and Feedback:

- Reciprocity also involves responding to problems in communication, such as misunderstanding or ambiguity. Speakers use repairs to clarify or correct these concerns. Listeners provide feedback such as "uh-huh" or nodding to show engagement and understanding.

- Social Norms and Obligations:

Reciprocity in non-human primates

[edit]The topic of reciprocity in non-human primates has been a field with a lot of research contradictions and opposite findings; however, in a recent meta-analysis, the researchers concluded that primates have the cognitive and social prerequisites needed to use reciprocity.[52] They evaluated previous findings and found that there are more positive than negative findings.[52] They added that reciprocity could have been misrepresented in some research studies because it also includes acting between relatives and trading.[52]

Researchers also identified that many of the negative findings come from articles where researchers did not measure the primate’s understanding of the task or studies where the primates did not show an understanding of the activity.[52] Previous researchers interpreted studies that did not display reciprocity as a failure to prove its existence in primates, rather than assessing the situations where reciprocity occurred versus the situations where it did not.[52] Different species also take different time periods to reciprocate an action which may be short or long-term.[52] Some specific behaviors also seem less likely to be reciprocated.[52] For example, it is less likely for a non-human primate to reciprocate food donations.[52]

Overall, the researchers concluded that non-human primate reciprocity is more common than it has previously been regarded and that negative findings should not be thrown out but instead embraced to foster a better comprehension of their use of reciprocity.[52] News sources also support these findings suggesting that other primates use reciprocity in food sharing and other domains; and some of them, like chimpanzees, are more likely to do so if the other chimpanzee had also helped them in the past, which also supports the connection between trust and reciprocity in non-human primates.[53]

See also

[edit]- Ben Franklin effect

- Cooperation

- Generalized exchange

- Homo reciprocans

- Influence: Science and Practice

- Norm of reciprocity

- Prisoner's dilemma

- Reciprocal altruism

- Reciprocity (cultural anthropology)

- Reciprocity (international relations)

- Reciprocity (social and political philosophy)

References

[edit]- ^ Nowakowska, Iwona; Abramiuk-Szyszko, Agnieszka (2023). "Reciprocity". Encyclopedia of Sexual Psychology and Behavior. Springer, Cham. pp. 1–10. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-08956-5_1983-1. ISBN 978-3-031-08956-5.

- ^ "Definition: Reciprocity bias". Association for Qualitative Research (AQR). Retrieved 2024-12-07.

- ^ Tuttle, Harold S. (1934), "Altruism.", A social basis of education., New York: Thomas Y Crowell Co, pp. 468–476, doi:10.1037/14717-032, retrieved 2024-12-07

- ^ "What Is Altruism? Examples and Types of Altruistic Behavior". Psych Central. 2022-05-25. Retrieved 2024-12-07.

- ^ "Code of Hammurabi: Laws & Facts". HISTORY. 2024-08-07. Retrieved 2024-12-07.

- ^ Konstan, David (1998-05-28), "Reciprocity and Friendship", Reciprocity in Ancient Greece, Oxford University PressOxford, pp. 279–302, ISBN 978-0-19-814997-2, retrieved 2024-12-07

- ^ Homer (1990). The Iliad. (B. Knox, Ed. R. Fagles, Trans.). New York, NY: Penguin Classics.

- ^ Homer (2014-01-30), "Iliad", The Iliad, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-992586-5, retrieved 2024-12-07

- ^ "The Greek Ideals". merkspages.com. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- ^ Homer (2014-10-09), "Odyssey", The Odyssey, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-992588-9, retrieved 2024-12-07

- ^ Saller, Richard P. (2002-05-09). Personal Patronage Under the Early Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521893923.

- ^ Coffee, Neil (2013-01-01). "Reciprocity". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah06274. ISBN 9781444338386.

- ^ "leakey and lewin 1978 - Google Scholar". scholar.google.com. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- ^ Ridley, M. (1997). The origins of virtue. UK: Penguin UK.

- ^ a b c d Fehr, Ernst; Gächter, Simon (2000). "Fairness and Retaliation: The Economics of Reciprocity". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 14 (3): 159–182. doi:10.1257/jep.14.3.159. hdl:10419/75602.

- ^ Paese, Paul W.; Gilin, Debra A. (2000-01-01). "When an Adversary is Caught Telling the Truth: Reciprocal Cooperation Versus Self-Interest in Distributive Bargaining". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 26 (1): 79–90. doi:10.1177/0146167200261008. ISSN 0146-1672. S2CID 146148164.

- ^ a b Regan, Dennis T. (1971-11-01). "Effects of a favor and liking on compliance". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 7 (6): 627–639. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(71)90025-4. S2CID 18429974.

- ^ Kunz, Phillip R; Woolcott, Michael (1976-09-01). "Season's greetings: From my status to yours". Social Science Research. 5 (3): 269–278. doi:10.1016/0049-089X(76)90003-X.

- ^ Fehr, Ernst; Gächter, Simon (2000-09-01). "Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments". American Economic Review. 90 (4): 980–994. doi:10.1257/aer.90.4.980. hdl:10419/75478. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ Fehr, Ernst; Gächter, Simon (2000-01-01). "Fairness and Retaliation: The Economics of Reciprocity". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 14 (3): 159–181. doi:10.1257/jep.14.3.159. hdl:10419/75602. JSTOR 2646924.

- ^ Killingback, Timothy; Doebeli, Michael (1 October 2002). "The Continuous Prisoner's Dilemma and the Evolution of Cooperation through Reciprocal Altruism with Variable Investment". The American Naturalist. 160 (4): 421–438. doi:10.1086/342070. ISSN 0003-0147 – via The University of Chicago Press Journals.

- ^ a b "Trade: Chapter 125-7: Positive Reciprocity". internationalecon.com. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ a b Caliendo, Marco; Fossen, Frank; Kritikos, Alexander (2012-04-01). "Trust, positive reciprocity, and negative reciprocity: Do these traits impact entrepreneurial dynamics?" (PDF). Journal of Economic Psychology. Personality and Entrepreneurship. 33 (2): 394–409. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2011.01.005. hdl:10419/150893.

- ^ a b Chen, Ya-Ru; Chen, Xiao-Ping; Portnoy, Rebecca (2009-01-01). "To whom do positive norm and negative norm of reciprocity apply? Effects of inequitable offer, relationship, and relational-self orientation". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 45 (1): 24–34. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2008.07.024.

- ^ Molm, Linda D.; Schaefer, David R.; Collett, Jessica L. (May 2007). "The Value of Reciprocity". Social Psychology Quarterly. 70 (2): 199–217. doi:10.1177/019027250707000208. ISSN 0190-2725.

- ^ Tidd, Kathi L.; Lockard, Joan S. (2013-11-14). "Monetary significance of the affiliative smile: A case for reciprocal altruism". Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 11 (6): 344–346. doi:10.3758/BF03336849. ISSN 0090-5054.

- ^ Hollingworth, Crawford (2015-07-28). "Bias in the Spotlight: Reciprocity". research-live.com. The Market Research Society. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ "Trade: Chapter 125-8: Negative Reciprocity". internationalecon.com. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ Sahlins, Marshall (1972). Stone Age Economics. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. p. 195.

- ^ a b c d Cialdini, Robert B.; Vincent, Joyce E.; Lewis, Stephen K.; Catalan, Jose; Wheeler, Diane; Darby, Betty Lee (1 February 1975). "Reciprocal concessions procedure for inducing compliance: The door-in-the-face technique". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 31 (2): 206–215. doi:10.1037/h0076284. ISSN 1939-1315.

- ^ Staff, P. O. N. (2024-11-19). "Negotiation Skills: Building Trust in Negotiations". PON - Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ McAuliffe, Katherine; Dunham, Yarrow (2016-01-19). "Group bias in cooperative norm enforcement". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 371 (1686): 20150073. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0073. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 4685519. PMID 26644592.

- ^ Herr, Paul M; Sherman, Steven J; Fazio, Russell H (July 1983). "On the consequences of priming: Assimilation and contrast effects". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 19 (4): 323–340. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(83)90026-4. ISSN 0022-1031.

- ^ Pascual, Alexandre; Guéguen, Nicolas (2005-02-01). "Foot-in-the-door and door-in-the-face: a comparative meta-analytic study". Psychological Reports. 96 (1): 122–128. doi:10.2466/pr0.96.1.122-128. ISSN 0033-2941. PMID 15825914. S2CID 19701668.

- ^ Tusing, Kyle James; Dillard, James Price (2000-03-01). "The Psychological Reality of the Door-in-the-Face It's Helping, not Bargaining". Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 19 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1177/0261927X00019001001. ISSN 0261-927X. S2CID 144775958.

- ^ Schwarzwald, Joseph; Raz, Moshe; Zvibel, Moshe (1979-12-01). "The Applicability of the Door-in-the Face Technique when Established Behavioral Customs Exist". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 9 (6): 576–586. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1979.tb00817.x. ISSN 1559-1816.

- ^ Burger, J.M. (1999). "The foot-in-the-door compliance procedure: A multiple-process analysis and review". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 3 (4): 303–325. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0304_2. PMID 15661679. S2CID 1391814.

- ^ Cialdini, Robert (2018). "Speaking of Psychology: The Power of Persuasion". PsycEXTRA Dataset. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ Cialdini, Robert B. (2005). Influence: science and practice (4. ed., 14. print ed.). Boston, Mass.: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-321-01147-3.

- ^ Torche, Florencia; Valenzuela, Eduardo (May 2011). "Trust and reciprocity: A theoretical distinction of the sources of social capital". European Journal of Social Theory. 14 (2): 181–198. doi:10.1177/1368431011403461. ISSN 1368-4310.

- ^ Buunk, Bram P.; Doosje, Bert Jan; Jans, Liesbeth G. J. M.; Hopstaken, Liliane E. M. (October 1993). "Perceived reciprocity, social support, and stress at work: The role of exchange and communal orientation". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 65 (4): 801–811. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.801. ISSN 1939-1315.

- ^ a b Siegrist, Johannes (November 2005). "Social reciprocity and health: New scientific evidence and policy implications". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 30 (10): 1033–1038. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.017. ISSN 0306-4530. PMID 15951124.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Greco, Lindsey M.; Whitson, Jennifer A.; O'Boyle, Ernest H.; Wang, Cynthia S.; Kim, Joongseo (2019-09-01). "An eye for an eye? A meta-analysis of negative reciprocity in organizations". Journal of Applied Psychology. 104 (9): 1117–1143. doi:10.1037/apl0000396. ISSN 1939-1854. PMID 30762379. S2CID 73420919.

- ^ a b Lopez, Anthony C. (2015-03-24). ""Why Evolution Made Forgiveness Difficult"". Greater Good Magazine. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ^ a b c d e f Bellucci, Gabriele; Chernyak, Sergey V.; Goodyear, Kimberly; Eickhoff, Simon B.; Krueger, Frank (2017-03-01). "Neural signatures of trust in reciprocity: A coordinate-based meta-analysis: Neural Signatures of Trust in Reciprocity". Human Brain Mapping. 38 (3): 1233–1248. doi:10.1002/hbm.23451. PMC 5441232. PMID 27859899.

- ^ Suttie, Jill (2017-10-05). "What Makes People Cooperate with Strangers?". Greater Good Magazine. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Katzir, Maayan; Cohen, Shachar; Halali, Eliran (2021-11-01). "Is it all about appearance? Limited cognitive control and information advantage reveal self-serving reciprocity". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 97: 104192. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104192. ISSN 0022-1031. S2CID 237654239.

- ^ Collins, Nathan (2015-06-20). ""What Drives Selfless Acts?"". Greater Good Magazine. Retrieved 2023-04-18.

- ^ a b Sacks, Harvey; Schegloff, Emanuel A.; Jefferson, Gail (December 1974). "A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation". Language. 50 (4): 696. doi:10.2307/412243. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002C-4337-3. ISSN 0097-8507.

- ^ Ephratt, Michal (2012). ""We try harder" - Silence and Grice's cooperative principle, maxims and implicatures". PsycEXTRA Dataset. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ Brown, Penelope; Levinson, Stephen C.; Gumperz, John J. (1987-02-27). Politeness. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30862-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schweinfurth, Manon K.; Call, Josep (2019-09-01). "Revisiting the possibility of reciprocal help in non-human primates". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 104: 73–86. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.026. hdl:10023/20113. ISSN 0149-7634. PMID 31260701. S2CID 195770897.

- ^ Suchak, Malini (2017-02-01). ""The Evolution of Gratitude"". Greater Good Magazine. Retrieved 2023-04-17.