Arthur "Slim" Evans

Arthur "Slim" Evans | |

|---|---|

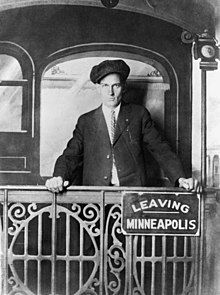

Arthur "Slim" Evans, c. 1911 | |

| Born | Arthur Herbert Evans April 24, 1890 |

| Died | February 13, 1944 (aged 53) |

| Occupation(s) | Trade Unionist, carpenter |

| Organizations | |

| Known for | Leading the On to Ottawa Trek |

| Political party | Communist Party of Canada |

Arthur Herbert "Slim" Evans (April 24, 1890 – February 13, 1944) was a leader in the industrial labour union movement in Canada and the United States.[1] He is most known for leading the On To Ottawa Trek. Evans was involved in the Industrial Workers of the World, the One Big Union, and the Worker's Unity League. He was a member of the Communist Party of Canada.[2]

Personal life

[edit]Evans was born in Toronto in 1890. At age 13, he left school to support his family. He worked numerous jobs, including horse driver and carpenter. Evans travelled west in 1911 and worked in various places, first as a farmer, then worked again as a carpenter in Winnipeg, Minneapolis and Kansas City.[3]

On August 4, 1920, Arthur "Slim" Evans married Ethel Hawkins, who he had met while organizing miners in Drumheller, Alberta. On April 13, 1922, the couple had their first child, a son named Stewart. Stewart Evans died in 1925 during the diphtheria epidemic in Vancouver. They had a second child, Jean Stewart Evans, on February 12, 1927. Jean would go on to write "Work and Wages!", a biography of her father.

Wobblies

[edit]In Minneapolis he became involved with the Industrial Workers of the World, (IWW, or "Wobblies"). He led an IWW free speech rally in Minneapolis where he was arrested for participating and sentenced to three years in jail. Evans later recalled: "All I did was read it. I was too shy and too nervous at that time to make up any speech of my own."[4] In 1912, he led a strike of political prisoners resulting in his release.

He was present at the 1913 miners' strike in Ludlow, Colorado. There he met IWW leaders "Big" Bill Haywood, Frank Little, and the legendary Joe Hill. Two days after Evans arrived, strikebreakers hired by John D. Rockefeller, owner of the coal mines, attacked the striker's camp, killing 20 people including 12 children in the Ludlow Massacre.[5] Evans was shot in the leg with a machine gun. He walked with a limp for the rest of his life as a result.[6]

Evans returned to Canada and continued his union activism. He was the leader of the One Big Union local of coal miners in Drumheller, Alberta. He led a strike of 6,300 One Big Union miners during the Canadian Labour Revolt in 1919. It was there he met his future wife Ethel, daughter of a Drumheller miner who had been involved in organizing the union.[3] The strike was suppressed by anti-union mercenaries hired by the mining company. Because the One Big Union was not a recognized union, and workers were official organized within the United Mine Workers, Evans had technically organized a 'wild cat' strike without permission. Evans used UMWA funds for the strike, he was accused of embezzlement and sentenced to a three year prison term.[7] Upon a petition from the workers he supposedly embezzled from, Evans was released.[1]

Evans, along with other former wobblies, became a member of the Communist Party of Canada after it formed in 1921. Evans officially became a party member in 1926.[8]

Worker's Unity League

[edit]The Worker's Unity League was the official trade union centre of the Communist Party of Canada. Like the IWW and OBU which Evans had previously organized in, the Worker's Unity League was an industrial union.[9] Evans was a major organizer within the union.[10]

Princeton coal miner's strike

[edit]In 1932, coal miners saw their wages cut by 10% in Princeton, British Columbia. The miners contacted the Worker's Unity League, which sent Evans to organize a union for them in September 1932.[11] The company refused to negotiate with the union, so the workers voted to strike. Evans advised the workers to wait until December to strike, because the demand for coal would be much higher. The strike began on December 22. British Columbia's attorney general dispatched a crops of 40 RCMP officers to monitor Evans and suppress the strike. Officers assaulted the striking miners with batons, along with their families, while they were picketing. The Ku Klux Klan burned crosses, beat strikers, and sent threatening letters, in the name of anti-communism.[12]

Evans was arrested under Section 98, which allows arbitrary detainment of suspected communists,. He was imprisoned in far off Oakella Prison where he did hard-labour before being released on bail. During his imprisonment, his wife and daughter were evicted from the home Evan's had built for them.[13] Following his release, Evans was kidnapped by off duty police constables and klansmen. A convoy of armed cars took him to Vancouver.[14] The kidnappers threatened: "take warning and move on or suffer the consequences". Evans immediately booked a train back to Princeton, where he led the strike to success, winning workers higher pay and improved workplace safety.[15] Evans was once again arrested under Section 98, and sentenced to one year in prison without bail. He rejected the legitimacy of the trial and instead of defending himself he sang The Internationale.[16]

On-to-Ottawa trek

[edit]In 1935 Evans led the On-to-Ottawa Trek. Communist activists including Evans had organized workers in the government relief camps into the Relief Camp Workers' Union three years previously in 1932. Relief camp workers struck on April 4, 1935, when they went to Vancouver, where they stayed and pressed their demands until the Trek began on June 3.[17] The first batch of strikers left Vancouver, riding on boxcars, and were joined by many others in Kamloops, Field, Golden, Calgary and Moose Jaw.[18] By the time they reached Regina, Saskatchewan their numbers had climbed to over 2,000. Evans led a delegation to go ahead of the strikers and meet with the prime minister, R. B. "Iron Heel" Bennett. The two leaders engaged in a heated exchange, when Bennett accused Evans of being an embezzler. Evans' response received much publicity:

You are a liar. I was arrested for fraudulently converting these funds to feed the starving, instead of sending them to the agents at Indianapolis, and I again say you are a liar if you say I embezzled, and I will have the pleasure of telling the workers throughout Canada that I was forced to tell the premier of Canada he was a liar. Don't think you can pull off anything like that. You are not intimidating me a damned bit.[19]

The meeting accomplished little more than to illustrate the intransigence of the government and the determination of the strikers, and the delegation left Ottawa to rejoin the strikers in Regina.

Evans and other Trek leaders were arrested at a large demonstration of strikers and supporters on July 1, 1935, (Dominion Day, or Canada Day, as it is now called), which precipitated the Regina Riot. The federal government had decided that the Trek would be forcibly stopped in Regina because of fears that it would gain momentum if allowed to reach Winnipeg that could turn it from a protest into a revolutionary movement.[20]

Evans was charged under Section 98, the section of the Criminal Code, which had been added in the aftermath of the Winnipeg General Strike outlawing membership in revolutionary organizations. An exhaustive government inquiry was held into causes of the riot, and its conclusions paved the way for reforming the relief camp system. This outcome and the overwhelming defeat of R. B. Bennett are two indicators that the strike was a success, even though the Trek was crushed.[21][22]

Later organizing

[edit]Evans continued his union activism, organizing the miners and smelter workers in Trail, British Columbia, into the CIO union, Mine, Mill, and Smelters Union. While organizing the smelters, his car was torched by the mine owners.[23] He also led fundraising drives for the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, the volunteer contingent from Canada that fought the fascists during the Spanish Civil War. His last union position was as the shop steward at the Vancouver Shipyards.[24]

Death

[edit]He died in Vancouver on February 13, 1944, aged 53. After leaving a street car, he was struck by a motorist crossing between streets Kingsway and Joyce.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "EVANS, ARTHUR "SLIM" (1890–1944)". The Encyclopaedia of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on May 22, 2023. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ "Arthur Evans". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Laszlo, Krisztina. "Research Guides: Labour History and Archives: Arthur H. Evans fonds". guides.library.ubc.ca. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Evans Slim". ABC BookWorld. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Jean Evans Sheils and Ben Swankey, "Work and Wages"! A Semi-Documentary Account of the Life and Times of Arthur H. (Slim) Evans . Vancouver: Trade Union Research Bureau, 1977, 10.

- ^ Jean Evans Sheils and Ben Swankey, "Work and Wages"! A Semi-Documentary Account of the Life and Times of Arthur H. (Slim) Evans. Vancouver: Trade Union Research Bureau, 1977, 6.

- ^ ""For We Are Coming!"". The Chesterfield. January 12, 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Jean Evans Sheils and Ben Swankey, "Work and Wages"! A Semi-Documentary Account of the Life and Times of Arthur H. (Slim) Evans. Vancouver: Trade Union Research Bureau, 1977, 32.

- ^ "Workers Unity League". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Brown, Lorne (1987). When freedom was lost : the unemployed, the agitator, and the state. Black Rose Books. OCLC 645872570.

- ^ Endicott, Stephen (2012). Raising the Workers' Flag: The Workers' Unity League of Canada, 1930–1936'. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442612266. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt2tv3b7.

- ^ "Communism, kidnapping and the KKK: Book recounts hysteria of Princeton's 1930s miners' strike". CBC News. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Vancouver house has Slim history". Vancouver Is Awesome. July 3, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Palmer, Bryan D. (March 31, 2016). "Fighting the Klan". Literary Review of Canada. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Manley, John (February 9, 2006). "Canadian Communists, Revolutionary Unionism, and the 'Third Period': The Workers' Unity League, 1929–1935". Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada. 5 (1): 167–194. doi:10.7202/031078ar. ISSN 1712-6274.

- ^ Hannant, Larry (2016). "Soviet Princeton: Slim Evans and the 1932–33 Miners' Strike by Jon Bartlett and Rika Ruebsaat". Labour / Le Travail. 78 (1): 336–337. doi:10.1353/llt.2016.0070. ISSN 1911-4842.

- ^ "Archival Find Confirms 1935 Golden Tale from 'On-to-Ottawa' Trek – Working People Built BC". www.labourheritagecentre.ca. October 11, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Horn, Michiel; Howard, Victor (1987). ""We Were the Salt of the Earth!" A Narrative of the On-to-Ottawa Trek and the Regina Riot". Labour / Le Travail. 19: 177. doi:10.2307/25142781. ISSN 0700-3862. JSTOR 25142781.

- ^ Ronald Liversedge, Recollections of the On-to-Ottawa Trek, ed. Victor Hoar, Toronto: McLelland and Stewart, 1973, 210–211.

- ^ "On to Ottawa Trek and Regina Riot". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "On to Ottawa Trek". cbc.ca. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Relief Strikes: The On-to-Ottawa Trek and Bloody Sunday – The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion". onlineacademiccommunity.uvic.ca. Archived from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Wilbur, Richard; Abella, Irving Martin (June 1976). "Nationalism, Communism, and Canadian Labour: The CIO, the Communist Party, and the Canadian Congress of Labour, 1935–1956". The American Historical Review. 81 (3): 697. doi:10.2307/1852654. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 1852654.

- ^ Gollan, Robin; Avakumovic, Ivan (1976). "The Communist Party in Canada: a History". Labour History (31): 97. doi:10.2307/27508243. ISSN 0023-6942. JSTOR 27508243.

- ^ Waiser, Bill (2003). All Hell Can't Stop Us: The On-to-Ottawa Trek and Regina Riot. Calgary: Fifth House. p. 273.

- 1890 births

- 1944 deaths

- People from the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary

- People from Minneapolis

- People from Old Toronto

- Pedestrian road incident deaths

- Industrial Workers of the World members

- Members of the Communist Party of Canada

- Canadian people of Welsh descent

- Canadian expatriates in the United States

- Road incident deaths in Canada

- Accidental deaths in British Columbia

- Trade unionists from Ontario

- One Big Union (Canada) members