Fox

| Foxes | |

|---|---|

| |

| A red fox in Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Subfamily: | Caninae |

| Groups included | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

|

All other species in Canini | |

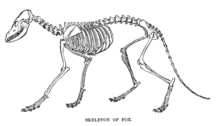

Foxes are small-to-medium-sized omnivorous mammals belonging to several genera of the family Canidae. They have a flattened skull; upright, triangular ears; a pointed, slightly upturned snout; and a long, bushy tail ("brush").

Twelve species belong to the monophyletic "true fox" group of genus Vulpes. Another 25 current or extinct species are sometimes called foxes – they are part of the paraphyletic group of the South American foxes or an outlying group, which consists of the bat-eared fox, gray fox, and island fox.[1]

Foxes live on every continent except Antarctica. The most common and widespread species of fox is the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) with about 47 recognized subspecies.[2] The global distribution of foxes, together with their widespread reputation for cunning, has contributed to their prominence in popular culture and folklore in many societies around the world. The hunting of foxes with packs of hounds, long an established pursuit in Europe, especially in the British Isles, was exported by European settlers to various parts of the New World.

Etymology

The word fox comes from Old English and derives from Proto-Germanic *fuhsaz.[nb 1] This in turn derives from Proto-Indo-European *puḱ- "thick-haired, tail."[nb 2] Male foxes are known as dogs, tods, or reynards; females as vixens; and young as cubs, pups, or kits, though the last term is not to be confused with the kit fox, a distinct species. "Vixen" is one of very few modern English words that retain the Middle English southern dialectal "v" pronunciation instead of "f"; i.e., northern English "fox" versus southern English "vox".[3] A group of foxes is referred to as a skulk, leash, or earth.[4][5]

Phylogenetic relationships

Within the Canidae, the results of DNA analysis shows several phylogenetic divisions:

- The fox-like canids, which include the kit fox (Vulpes velox), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), Cape fox (Vulpes chama), Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus), and fennec fox (Vulpes zerda).[6]

- The wolf-like canids, (genus Canis, Cuon and Lycaon) including the dog (Canis lupus familiaris), gray wolf (Canis lupus), red wolf (Canis rufus), eastern wolf (Canis lycaon), coyote (Canis latrans), golden jackal (Canis aureus), Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis), black-backed jackal (Canis mesomelas), side-striped jackal (Canis adustus), dhole (Cuon alpinus), and African wild dog (Lycaon pictus).[6]

- The South American canids, including the bush dog (Speothos venaticus), hoary fox (Lycalopex uetulus), crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) and maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus).[6]

- Various monotypic taxa, including the bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis), gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), and raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides).[6]

Biology

General morphology

Foxes are generally smaller than some other members of the family Canidae such as wolves and jackals, while they may be larger than some within the family, such as raccoon dogs. In the largest species, the red fox, males weigh between 4.1 and 8.7 kg (9.0 and 19.2 lb),[7] while the smallest species, the fennec fox, weighs just 0.7 to 1.6 kg (1+1⁄2 to 3+1⁄2 lb).[8]

Fox features typically include a triangular face, pointed ears, an elongated rostrum, and a bushy tail. They are digitigrade (meaning they walk on their toes). Unlike most members of the family Canidae, foxes have partially retractable claws.[9] Fox vibrissae, or whiskers, are black. The whiskers on the muzzle, known as mystacial vibrissae, average 100–110 millimetres (3+7⁄8–4+3⁄8 inches) long, while the whiskers everywhere else on the head average to be shorter in length. Whiskers (carpal vibrissae) are also on the forelimbs and average 40 mm (1+5⁄8 in) long, pointing downward and backward.[2] Other physical characteristics vary according to habitat and adaptive significance.

Pelage

Fox species differ in fur color, length, and density. Coat colors range from pearly white to black-and-white to black flecked with white or grey on the underside. Fennec foxes (and other species of fox adapted to life in the desert, such as kit foxes), for example, have large ears and short fur to aid in keeping the body cool.[2][9] Arctic foxes, on the other hand, have tiny ears and short limbs as well as thick, insulating fur, which aid in keeping the body warm.[10] Red foxes, by contrast, have a typical auburn pelt, the tail normally ending with a white marking.[11]

A fox's coat color and texture may vary due to the change in seasons; fox pelts are richer and denser in the colder months and lighter in the warmer months. To get rid of the dense winter coat, foxes moult once a year around April; the process begins from the feet, up the legs, and then along the back.[9] Coat color may also change as the individual ages.[2]

Dentition

A fox's dentition, like all other canids, is I 3/3, C 1/1, PM 4/4, M 3/2 = 42. (Bat-eared foxes have six extra molars, totalling in 48 teeth.) Foxes have pronounced carnassial pairs, which is characteristic of a carnivore. These pairs consist of the upper premolar and the lower first molar, and work together to shear tough material like flesh. Foxes' canines are pronounced, also characteristic of a carnivore, and are excellent in gripping prey.[12]

Behaviour

In the wild, the typical lifespan of a fox is one to three years, although individuals may live up to ten years. Unlike many canids, foxes are not always pack animals. Typically, they live in small family groups, but some (such as Arctic foxes) are known to be solitary.[2][9]

Foxes are omnivores.[13][14] Their diet is made up primarily of invertebrates such as insects and small vertebrates such as reptiles and birds. They may also eat eggs and vegetation. Many species are generalist predators, but some (such as the crab-eating fox) have more specialized diets. Most species of fox consume around 1 kg (2.2 lb) of food every day. Foxes cache excess food, burying it for later consumption, usually under leaves, snow, or soil.[9][15] While hunting, foxes tend to use a particular pouncing technique, such that they crouch down to camouflage themselves in the terrain and then use their hind legs to leap up with great force and land on top of their chosen prey.[2] Using their pronounced canine teeth, they can then grip the prey's neck and shake it until it is dead or can be readily disemboweled.[2]

The gray fox is one of only two canine species known to regularly climb trees; the other is the raccoon dog.[16]

Sexual characteristics

The male fox's scrotum is held up close to the body with the testes inside even after they descend. Like other canines, the male fox has a baculum, or penile bone.[2][17][18] The testes of red foxes are smaller than those of Arctic foxes.[19] Sperm formation in red foxes begins in August–September, with the testicles attaining their greatest weight in December–February.[20]

Vixens are in heat for one to six days, making their reproductive cycle twelve months long. As with other canines, the ova are shed during estrus without the need for the stimulation of copulating. Once the egg is fertilized, the vixen enters a period of gestation that can last from 52 to 53 days. Foxes tend to have an average litter size of four to five with an 80 percent success rate in becoming pregnant.[2][21] Litter sizes can vary greatly according to species and environment – the Arctic fox, for example, can have up to eleven kits.[22]

The vixen usually has six or eight mammae.[23] Each teat has 8 to 20 lactiferous ducts, which connect the mammary gland to the nipple, allowing for milk to be carried to the nipple.[citation needed]

Vocalization

The fox's vocal repertoire is vast, and includes:

- Whine

- Made shortly after birth. Occurs at a high rate when kits are hungry and when their body temperatures are low. Whining stimulates the mother to care for her young; it also has been known to stimulate the male fox into caring for his mate and kits.

- Yelp

- Made about 19 days later. The kits' whining turns into infantile barks, yelps, which occur heavily during play.

- Explosive call

- At the age of about one month, the kits can emit an explosive call which is intended to be threatening to intruders or other cubs; a high-pitched howl.

- Combative call

- In adults, the explosive call becomes an open-mouthed combative call during any conflict; a sharper bark.

- Growl

- An adult fox's indication to their kits to feed or head to the adult's location.

- Bark

- Adult foxes warn against intruders and in defense by barking.[2][24]

In the case of domesticated foxes, the whining seems to remain in adult individuals as a sign of excitement and submission in the presence of their owners.[2]

Classification

Canids commonly known as foxes include the following genera and species:[2]

| Genus | Species | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| Canis | Ethiopian wolf, sometimes called the Simien fox or Simien jackal |  |

| Cerdocyon | Crab-eating fox |  |

| † Dusicyon | Extinct genus, including the Falkland Islands wolf, sometimes known as the Falklands Islands fox |  |

| Lycalopex |

|

|

| Otocyon | Bat-eared fox |  |

| Urocyon |

|

|

| Vulpes |  |

Conservation

Several fox species are endangered in their native environments. Pressures placed on foxes include habitat loss and being hunted for pelts, other trade, or control.[25] Due in part to their opportunistic hunting style and industriousness, foxes are commonly resented as nuisance animals.[26] Contrastingly, foxes, while often considered pests themselves, have been successfully employed to control pests on fruit farms while leaving the fruit intact.[27]

Urocyon littoralis

The island fox, though considered a near-threatened species throughout the world, is becoming increasingly endangered in its endemic environment of the California Channel Islands.[28] A population on an island is smaller than those on the mainland because of limited resources like space, food and shelter.[29] Island populations are therefore highly susceptible to external threats ranging from introduced predatory species and humans to extreme weather.[29]

On the California Channel Islands, it was found that the population of the island fox was so low due to an outbreak of canine distemper virus from 1999 to 2000[30] as well as predation by non-native golden eagles.[31] Since 1993, the eagles have caused the population to decline by as much as 95%.[30] Because of the low number of foxes, the population went through an Allee effect (an effect in which, at low enough densities, an individual's fitness decreases).[28] Conservationists had to take healthy breeding pairs out of the wild population to breed them in captivity until they had enough foxes to release back into the wild.[30] Nonnative grazers were also removed so that native plants would be able to grow back to their natural height, thereby providing adequate cover and protection for the foxes against golden eagles.[31]

Pseudalopex fulvipes

Darwin's fox was considered critically endangered because of their small known population of 250 mature individuals as well as their restricted distribution.[32] However, the IUCN have since downgraded the conservation status from crictically endangered in their 2004 and 2008 assessments to endangered in the 2016 assessment, following findings of a wider distribution than previously reported.[33] On the Chilean mainland, the population is limited to Nahuelbuta National Park and the surrounding Valdivian rainforest.[32] Similarly on Chiloé Island, their population is limited to the forests that extend from the southernmost to the northwesternmost part of the island.[32] Though the Nahuelbuta National Park is protected, 90% of the species live on Chiloé Island.[34]

A major issue the species faces is their dwindling, limited habitat due to the cutting and burning of the unprotected forests.[32] Because of deforestation, the Darwin's fox habitat is shrinking, allowing for their competitor's (chilla fox) preferred habitat of open space, to increase; the Darwin's fox, subsequently, is being outcompeted.[35] Another problem they face is their inability to fight off diseases transmitted by the increasing number of pet dogs.[32] To conserve these animals, researchers suggest the need for the forests that link the Nahuelbuta National Park to the coast of Chile and in turn Chiloé Island and its forests, to be protected.[35] They also suggest that other forests around Chile be examined to determine whether Darwin's foxes have previously existed there or can live there in the future, should the need to reintroduce the species to those areas arise.[35] And finally, the researchers advise for the creation of a captive breeding program, in Chile, because of the limited number of mature individuals in the wild.[35]

Relationships with humans

Foxes are often considered pests or nuisance creatures for their opportunistic attacks on poultry and other small livestock. Fox attacks on humans are not common.[36] Many foxes adapt well to human environments, with several species classified as "resident urban carnivores" for their ability to sustain populations entirely within urban boundaries.[37] Foxes in urban areas can live longer and can have smaller litter sizes than foxes in non-urban areas.[37] Urban foxes are ubiquitous in Europe, where they show altered behaviors compared to non-urban foxes, including increased population density, smaller territory, and pack foraging.[38] Foxes have been introduced in numerous locations, with varying effects on indigenous flora and fauna.[39]

In some countries, foxes are major predators of rabbits and hens. Population oscillations of these two species were the first nonlinear oscillation studied and led to the derivation of the Lotka–Volterra equation.[40][41]

As food

Fox meat is edible, though it is not considered a common cuisine in any country.[42]

Hunting

Fox hunting originated in the United Kingdom in the 16th century. Hunting with dogs is now banned in the United Kingdom,[43][44][45][46] though hunting without dogs is still permitted. Red foxes were introduced into Australia in the early 19th century for sport, and have since become widespread through much of the country. They have caused population decline among many native species and prey on livestock, especially new lambs.[47] Fox hunting is practiced as recreation in several other countries including Canada, France, Ireland, Italy, Russia, United States and Australia.

Domestication

There are many records of domesticated red foxes and others, but rarely of sustained domestication. A recent and notable exception is the Russian silver fox,[48] which resulted in visible and behavioral changes, and is a case study of an animal population modeling according to human domestication needs. The current group of domesticated silver foxes are the result of nearly fifty years of experiments in the Soviet Union and Russia to de novo domesticate the silver morph of the red fox. This selective breeding resulted in physical and behavioral traits appearing that are frequently seen in domestic cats, dogs, and other animals, such as pigmentation changes, floppy ears, and curly tails.[49] Notably, the new foxes became more tame, allowing themselves to be petted, whimpering to get attention and sniffing and licking their caretakers.[50]

Urban settings

Foxes are among the comparatively few mammals which have been able to adapt themselves to a certain degree to living in urban (mostly suburban) human environments. Their omnivorous diet allows them to survive on discarded food waste, and their skittish and often nocturnal nature means that they are often able to avoid detection, despite their larger size.

Urban foxes have been identified as threats to cats and small dogs, and for this reason there is often pressure to exclude them from these environments.[51]

The San Joaquin kit fox is a highly endangered species that has, ironically, become adapted to urban living in the San Joaquin Valley and Salinas Valley of southern California. Its diet includes mice, ground squirrels, rabbits, hares, bird eggs, and insects, and it has claimed habitats in open areas, golf courses, drainage basins, and school grounds.[51]

Though rare, bites by foxes have been reported; in 2018, a woman in Clapham, London was bitten on the arm by a fox after she had left the door to her flat open.[52]

In popular culture

The fox appears in many cultures, usually in folklore. There are slight variations in their depictions. In European, Persian, East Asian, and Native American folklore, foxes are symbols of cunning and trickery—a reputation derived especially from their reputed ability to evade hunters. This is usually represented as a character possessing these traits. These traits are used on a wide variety of characters, either making them a nuisance to the story, a misunderstood hero, or a devious villain.

In East Asian folklore, foxes are depicted as familiar spirits possessing magic powers. Similar to in the folklore of other regions, foxes are portrayed as mischievous, usually tricking other people, with the ability to disguise as an attractive female human. Others depict them as mystical, sacred creatures who can bring wonder or ruin.[53] Nine-tailed foxes appear in Chinese folklore, literature, and mythology, in which, depending on the tale, they can be a good or a bad omen.[54] The motif was eventually introduced from Chinese to Japanese and Korean cultures.[55]

The constellation Vulpecula represents a fox.

Notes

- ^ Cf. West Frisian foks, Dutch vos, and German Fuchs.

- ^ Cf. Hindi pū̃ch 'tail', Tocharian B päkā 'tail; chowrie', and Lithuanian paustìs 'fur'. The bushy tail forms the basis for the fox's Welsh name, llwynog 'bushy', from llwyn 'bush'. Likewise, Portuguese: raposa from rabo 'tail', Lithuanian uodẽgis from uodegà 'tail', and Ojibwa waagosh from waa, which refers to the up-and-down "bounce" or flickering of an animal or its tail.

References

- ^ Macdonald, David W.; Sillero-Zubiri, Claudio, eds. (2004). The biology and conservation of wild canids (Nachdr. d. Ausg. 2004. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0198515562.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lloyd, H.G. (1981). The red fox (2. impr. ed.). London: Batsford. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7134-11904.

- ^ "Episode 113: A Zouthern Accent - The History of English Podcast". historyofenglishpodcast.com. 28 June 2018. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ Fellows, Dave. "Animal Congregations, or What Do You Call a Group of.....?". Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. USGS. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ "Fox Cubs and the breeding cycle". New Forest Explorers Guide. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d Wayne, Robert K. (June 1993). "Molecular evolution of the dog family". Trends in Genetics. 9 (6): 218–224. doi:10.1016/0168-9525(93)90122-x. PMID 8337763. Archived from the original on 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2017-11-25.

- ^ Larivière, S.; Pasitschniak-Arts, M. (1996). "Vulpes vulpes". Mammalian Species (537): 1–11. doi:10.2307/3504236. JSTOR 3504236.

- ^ Nobleman, Marc Tyler (2007). Foxes. Benchmark Books (NY). pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-7614-2237-2.

- ^ a b c d e Burrows, Roger (1968). Wild fox. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 9780715342176.

- ^ "Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus)". ARKive. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ Fox, David. "Vulpes vulpes, red fox". Animal Diversity Web. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ "Canidae". The University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Fedriani, J.M.; T. K. Fuller; R. M. Sauvajot; E. C. York (2000-07-05). "Competition and intraguild predation among three sympatric carnivores" (PDF). Oecologia. 125 (2): 258–270. Bibcode:2000Oecol.125..258F. doi:10.1007/s004420000448. hdl:10261/54628. PMID 24595837. S2CID 24289407. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-06.

- ^ Fox, David L. (2007). "Vulpes vulpes (red fox)". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Archived from the original on 2019-01-06. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

- ^ Macdonald, David W. (26 April 2010). "Food Caching by Red Foxes and Some Other Carnivores". Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 42 (2): 170–185. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1976.tb00963.x. PMID 1007654.

- ^ Lavigne, Guillaume de (2015-03-19). Free Ranging Dogs – Stray, Feral or Wild?. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 9781326219529.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Čanády, Alexander. "Variability of the baculum in the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) from Slovakia." Zoology and Ecology 23.3 (2013): 165–170.

- ^ Bijlsma, Rob G. "Copulatory lock of wild red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in broad daylight. Archived 2017-08-29 at the Wayback Machine" Naturalist 80: 45–67.

- ^ Heptner, V. G.; Naumov, N. P. (1998). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Leiden u.a.: Brill. p. 341. ISBN 978-1886106819.

- ^ Heptner & Naumov 1998, p. 537

- ^ Parkes, I. W. Rowlands and A. S. (21 August 2009). "The Reproductive Processes of certain Mammals.-VIII. Reproduction in Foxes (Vulpes spp.)". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 105 (4): 823–841. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1935.tb06267.x.

- ^ Hildebrand, Milton (1952). "The Integument in Canidae". Journal of Mammalogy. 33 (4): 419–428. doi:10.2307/1376014. JSTOR 1376014.

- ^ Ronald M. Nowak (2005). Walker's Carnivores of the World. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8032-2. Archived from the original on 2023-11-29. Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- ^ Tembrock, Günter (1976). "Canid vocalizations". Behavioural Processes. 1 (1): 57–75. doi:10.1016/0376-6357(76)90007-3. PMID 24923545. S2CID 205107627.

- ^ Ginsburg, Joshua Ross and David Whyte MacDonald. Foxes, Wolves, Jackals, and Dogs Archived 2023-11-30 at the Wayback Machine. p.58.

- ^ Bathgate, Michael. The Fox's Craft in Japanese Religion and Culture Archived 2023-11-29 at the Wayback Machine. 2004. p.18.

- ^ McCandless, Linda Foxes are Beneficial on Fruit Farms. nysaes.cornell.edu (1997-04-24)

- ^ a b ANGULO, ELENA; ROEMER, GARY W.; BEREC, LUDĚK; GASCOIGNE, JOANNA; COURCHAMP, FRANCK (29 May 2007). "Double Allee Effects and Extinction in the Island Fox" (PDF). Conservation Biology. 21 (4): 1082–1091. Bibcode:2007ConBi..21.1082A. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00721.x. hdl:10261/57044. PMID 17650257. S2CID 16545913. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-20.

- ^ a b Primack, Richard B. (2014). Essentials of conservation biology (Sixth ed.). Sinauer Associates. pp. 143–146. ISBN 9781605352893.

- ^ a b c Kohlmann, Stephan G.; Schmidt, Gregory A.; Garcelon, David K. (10 April 2005). "A population viability analysis for the Island Fox on Santa Catalina Island, California". Ecological Modelling. 183 (1): 77–94. Bibcode:2005EcMod.183...77K. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2004.07.022.

- ^ a b "Channel Islands: The Restoration of the Island Fox". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Jiménez, J. E. (2006). "Ecology of a coastal population of the critically endangered Darwin's fox (Pseudalopex fulvipes) on Chiloé Island, southern Chile". Journal of Zoology. 271 (1): 63–77. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00218.x.

- ^ Silva-Rodríguez, E.; Farias, A.; Moreira-Arce, D.; Cabello, J.; Hidalgo-Hermoso, E.; Lucherini, M. & Jiménez, J. (2016). "Lycalopex fulvipes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T41586A85370871.

- ^ Jiménez, J.E.; Lucherini, M. & Novaro, A.J. (2008). "Pseudalopex fulvipes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d Yahnke, Christopher J.; Johnson, Warren E.; Geffen, Eli; Smith, Deborah; Hertel, Fritz; Roy, Michael S.; Bonacic, Cristian F.; Fuller, Todd K.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Wayne, Robert K. (1996). "Darwin's Fox: A Distinct Endangered Species in a Vanishing Habitat". Conservation Biology. 10 (2): 366–375. Bibcode:1996ConBi..10..366Y. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10020366.x.

- ^ Barratt, Sarah and Martin Barratt. Practical Quail-keeping Archived 2023-11-29 at the Wayback Machine. 2013.

- ^ a b Iossa, G. et al. A Taxonomic Analysis of Urban Carnivore Ecology Archived 2023-11-30 at the Wayback Machine, from Urban Carnivores. Stanley Gehrt et al. eds. 2010. p.174.

- ^ Francis, Robert and Michael Chadwick. Urban Ecosystems Archived 2023-11-29 at the Wayback Machine 2013. p.126.

- ^ See generally Long, John. Introduced Mammals of the World Archived 2023-11-29 at the Wayback Machine. 2013.

- ^ Sprott, Julien. Elegant Chaos Archived 2023-11-29 at the Wayback Machine 2010. p.89.

- ^ Komarova, Natalia. Axiomatic Modeling in Life Sciences Archived 2023-11-29 at the Wayback Machine, from Mathematics and Life Sciences. Alexandra Antoniouk and Roderick Melnik, eds. pp.113–114.

- ^ Roland, Denise (2 January 2014). "Donkey snack contaminated by fox meat, fears Walmart". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "Hunt campaigners lose legal bid". BBC News Online. 2006-06-23. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ Singh, Anita (2009-09-18). "David Cameron 'to vote against fox hunting ban'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ Fox Hunting. North West League Against Cruel Sports Support Group. nwlacs.co.uk

- ^ "Fox Hunting: For and Against" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: European Red Fox, Department of the Environment, Australian Government". Archived from the original on 2015-12-23. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- ^ "The most affectionate foxes are bred in Novosibirsk". Redhotrussia. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- ^ Trut, Lyudmila N. (1999). "Early Canid Domestication: The Fox Farm Experiment" (PDF). American Scientist. 87 (2): 160. Bibcode:1999AmSci..87.....T. doi:10.1511/1999.2.160. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2003-03-13.

- ^ Kenneth Mason, Jonathan Losos, Susan Singer, Peter Raven, George Johnson(2011)Biology Ninth Edition, p. 423. McGraw-Hill, New York.ISBN 978-0-07-353222-6.

- ^ a b Clark E. Adams (15 June 2012). Urban Wildlife Management, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-4665-2127-8. Archived from the original on 29 November 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ Dunne, John; Moore-Bridger, Benedict; Powell, Tom (2018-06-21). "Woman mauled in bed by fox in Clapham flat: I'm traumatised and feared I would contract rabies". Evening Standard. London. Archived from the original on 2018-06-22. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2006). "The Fox in World Literature: Reflections on a "Fictional Animal"". Asian Folklore Studies. 65 (2): 133–160. JSTOR 30030396.

- ^ Kang, Xiaofei (2006). The cult of the fox: Power, gender, and popular religion in late imperial and modern China. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 15–21. ISBN 978-0-231-13338-8.

- ^ Wallen, Martin (2006). Fox. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9781861892973.

External links

- BBC Wales Nature: Fox videos

- The fox website[usurped]

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Fox". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- "Fox". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (9th ed.). 1879.

- "The Badger and the Fox". Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 38. April 1891. Reprinted from Cornhill Magazine.

- "Fox". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Fox". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Fox". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Fox". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "Fox". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.