Sinjar Mountains

| Sinjar | |

|---|---|

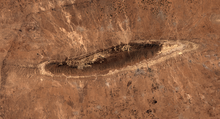

Terrace farming on Sinjar mountains | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,463 m (4,800 ft) |

| Coordinates | 36°22′0.22″N 41°43′18.62″E / 36.3667278°N 41.7218389°E |

| Geography | |

The Sinjar Mountains[1][2] (Kurdish: چیایێ شنگالێ, romanized: Çiyayê Şingalê, Arabic: جَبَل سِنْجَار, romanized: Jabal Sinjār, Syriac: ܛܘܪܐ ܕܫܝܓܪ, romanized: Ṭura d'Shingar),[3] are a 100-kilometre-long (62 mi) mountain range that runs east to west, rising above the surrounding alluvial steppe plains in northwestern Iraq to an elevation of 1,463 meters (4,800 ft). The highest segment of these mountains, about 75 km (47 mi) long, lies in the Nineveh Governorate. The western and lower segment of these mountains lies in Syria and is about 25 km (16 mi) long. The city of Sinjar is just south of the range.[4][5] These mountains are regarded as sacred by the Yazidis.[6][7]

Geology

[edit]

The Sinjar Mountains are a breached anticlinal structure.[4] These mountains consist of an asymmetrical, doubly plunging anticline, which is called the "Sinjar Anticline", with a steep northern limb, gentle southern limb and a northerly vergence. The northern side of the anticline is normally faulted, which results in the repetition of the sequence of sedimentary strata exposed in it. The deeply eroded Sinjar Anticline exposes a number of sedimentary formations ranging from Late Cretaceous to Early Neogene in age. The Late Cretaceous Shiranish Formation outcrops within the middle of the Sinjar Mountains. The flanks of this mountain range consist of outward dipping strata of the Sinjar and Aliji formations (Paleocene to Early Eocene); Jaddala Formation (Middle to Late Eocene); Serikagne Formation (Early Miocene); and Jeribe Formation (Early Miocene). The Sinjar Mountains are surrounded by exposures of Middle and Late Miocene sedimentary strata[5]

The mountain is a groundwater recharge area and should have good quality water, although away from the mountain groundwater quality is poor. Quantities are sufficient for agricultural and stock use.[8]

Sinjarite, a hygroscopic calcium chloride formed as soft pink mineral, was discovered in braided wadi fill, in limestone exposures near Sinjar.[9]

Population and history

[edit]| Part of a series on the Yazidi religion |

| Yazidism |

|---|

|

The Sinjar mountains already appear in the records from second and third millennium BCE under the name Saggar, which was also applied to a deity associated with the same area. In that period, the range was viewed as a source of basalt, as well as various nuts, especially pistachios, as evidenced by texts from Mari and Mesopotamia.[10]

The mountains primarily served as the border frontiers of empires throughout its history; it served as a battlefield between the Assyrians and the Hittite Empire, and was later occupied by the Parthians in 538 BC. The Roman Empire in turn occupied the mountains from the Parthians in 115 AD. From 363 AD, as a result of the Byzantine–Sasanian wars, the mountains lay on the Persian side of the frontier between the two empires. This Persian influence lasted for at least two hundred years and led to the introduction of Zoroastrianism in the region. In the 4th century, Christian influences on the mountains became well established, with Sinjar being part of the Nestorian Christian diocese of Nusaybin.[11] Starting in the late 5th century, the mountains became an abode of the Banu Taghlib, an Arab tribe.[12]

The region was conquered by the Arab Muslim general Iyad ibn Ghanm during the early Muslim conquests in the 630s–640s and came under Islamic rule, forming part of the Diyar Rabi'a district of the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) province.[12] The Christian inhabitants were allowed to practice their faith in exchange for payment of a poll tax.[11] The late 7th-century Syriac work, the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius, which was written in Sinjar, indicates Christian culture in the area declined during the first decades of Muslim rule.[12] The 9th-century Syriac patriarch Dionysius I Telmaharoyo records that a certain Atiq, possibly a Kharijite, raised a rebellion against the Umayyads in the Sinjar Mountains.[12] The medieval Arabic historian al-Mas'udi notes that a Kharijite sub-sect, the Ibadis, had a presence in the area.[12]

The Hamdanid dynasty, a branch of the Banu Taghlib, took over Sinjar in 970.[12] Toward the end of the century, Diyar Rabi'a was conquered by another Arab dynasty, the Uqaylids, who likely built the original citadel of Sinjar.[12] During this century, Yazidis are known to have inhabited the Sinjar Mountains,[12] and since the 12th century,[13] the area around the mountains have been mainly inhabited by Yazidis.[14] who venerate them and consider the highest to be the place where Noah's Ark settled after the biblical flood.[15] The Yazidis have historically used the mountains as a place of refuge and escape during periods of conflict. Gertrude Bell wrote, in the 1920s: "Until a couple of years ago the Yezidis were ceaselessly at war with the Arabs and with everybody else."[13]

The most prosperous period of Sinjar's history occurred in the 12th–13th centuries, beginning with the rule of the Turkmen atabeg Jikirmish in c. 1106–1107, through the high cultural period under a cadet branch of the Zengid dynasty and ending with Ayyubid rule.[12] The Armenian Mamluk ruler of Mosul, Badr ad-Din Lu'lu', in the first half of the 13th century, led a campaign against the Yazidis of the mountains, massacring Yazidis and desecrating the mausoleum of the Yazidi founder or reformer Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir in the Lalish valley.[16] During roughly the same era, Sunni Muslim Kurdish tribes launched widespread campaigns against the Yazidi population.[16]

During Ottoman rule, the historian Evliya Celebi noted that 45,000 Yazidis and so-called Baburi Kurds inhabited the Sinjar Mountains, while the city of Sinjar was inhabited by Kurds and Arabs of the Banu Tayy tribe.[12] The Yazidis often posed a threat to travelers through the mountains during the Ottoman era and revolted against the Empire in 1850–1864. The Ottomans were unable to impose their authority by force, but through the diplomatic efforts of the reformist statesman Midhat Pasha were able to impose taxes and customs in the Sinjar Mountains.[12] In the late 19th century, the Yazidis experienced religious persecution during campaigns by the Ottoman government, causing many to convert to Christianity to avoid the government's Islamization and conscription drives.[17]

In 1915 the Yazidis in Sinjar harbored many Armenians and Assyrians fleeing genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman government.[18]

Modern era

[edit]When the British gained control of the area after defeating the Ottomans in World War I, Sinjar became part of the British Mandate of Iraq. While British rule afforded the Yazidis a level of protection from religious persecution, it also contributed to the community's alienation from the nascent Kurdish nationalist movement.[17] Following Iraq's independence, the Yazidis of the Sinjar Mountains were the subject of land confiscations, military campaigns and attempts at conscription in the wars against the Kurdish nationalists in northern Iraq.[17] Starting in late 1974, the government of President Saddam Hussein launched a security project dubbed by the authorities as a "modernization drive" to ostensibly improve water, electricity and sanitation access for the villages in the Sinjar Mountains.[17] In practice, the central government sought to prevent Yazidis from joining the rebel Kurdish national movement of Mustafa Barzani, which collapsed in March 1975.[17] During the campaign, 137 mostly Yazidi villages were destroyed, most of which laid in or close to the Sinjar Mountains.[17] The inhabitants were then resettled in eleven new towns established 30–40 kilometers (19–25 mi) north or south of the mountains.[17] In 1976, the number of houses in the new towns, all of which bore Arabic names, were the following: 1,531 in Huttin, 1,334 in al-Qahtaniya, 1,300 in al-Bar, 1,195 in al-Tamin, 1,180 in al-Jazira, 1,120 in al-Yarmuk, 907 in al-Walid, 858 in al-Qadisiya, 838 in al-Adnaniya, 771 in al-Andalus and 510 in al-Uruba.[19] Five neighborhoods in the city of Sinjar were Arabized during this campaign; they were Bar Barozh, Saraeye, Kalhey, Burj and Barshey, whose inhabitants were relocated to the new towns or elsewhere in Iraq and replaced by Arabs.[19] In the censuses of 1977 and 1987, the Yazidis were mandated to register as Arabs and in the 1990s further lands in the region were redistributed to Arabs.[20]

Islamic State conflict

[edit]In August 2014, an estimated 40,000[21] to 50,000[22] Yazidis fled to the mountains following raids by Islamic State (IS) forces on the city of Sinjar, which fell to ISIL on August 3.[23] The Yazidi refugees on the mountain faced what a relief worker called a "genocide" at the hands of ISIS.[24] Stranded without water, food, shade, or medical supplies, the Yazidis had to rely on scarce[25] supplies of water and food airdropped by American,[26] British,[27] Australian,[28] and Iraqi forces.[29] By August 10, Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), People's Protection Units (YPG) and Kurdish Peshmerga forces defended some 30,000 of the Yezidis by opening a corridor from the mountains into nearby Rojava, through the Cezaa and Telkocher road, and from there into Iraqi Kurdistan.[30][31] Haider Sheshu commanded a militia that waged a guerilla war against ISIS.[32] Although thousands more remained stranded on the mountain as of August 12, 2014.[24] It has been reported that 7,000 Yazidi women were taken as slaves and over 5,000 men, women, and children were killed, some beheaded or buried alive in the foothills, as part of an effort to instill fear and to supposedly desecrate the mountain the Yazidis consider sacred.[26][31][33] Yezidi girls allegedly raped by ISIS fighters committed suicide by jumping to their death from Mount Sinjar, as described in a witness statement.[34]

See also

[edit]- İlandağ of the Lesser Caucasus in Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan

- List of Yazidi holy places

- List of Yazidi settlements

- Mount Judi in southeast Anatolia, Turkey

- Nuh or Noah

- Singara

References

[edit]- ^ Jabal Sinjār (Approved) at GEOnet Names Server, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- ^ جبل سنجار (Native Script) at GEOnet Names Server, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- ^ Thomas A. Carlson, “Mount Sinjar — ܛܘܪܐ ܕܫܝܓܪ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modified June 30, 2014, http://syriaca.org/place/524.

- ^ a b Edgell, H. S. 2006. Arabian Deserts: Nature, Origin, and Evolution. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 592 pp. ISBN 978-1-4020-3969-0

- ^ a b Numan, N. M. S., and N. K. AI-Azzawi. 2002. Progressive Versus Paroxysmal Alpine Folding in Sinjar Anticline Northwestern Iraq. Iraqi Journal of Earth Science. vol. 2, no.2, pp.59-69.

- ^ Phillips, David L. (7 October 2013). "Iraqi Kurds: "No Friend but the Mountains"". Huffington Post.

- ^ By Rudaw. "ISIS resumes attacks on Yezidis in Shingal". Rudaw.

- ^ Al-Sawaf, F.D.S. 1977. Hydrogeology of South Sinjar Plain Northwest Iraq. Doctoral thesis, University of London

- ^ Aljubouri, Zeki A.; Aldabbagh, Salim M. (March 1980), "Sinjarite, a new mineral from Iraq" (PDF), Mineralogical Magazine, 43 (329): 643–645, Bibcode:1980MinM...43..643A, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.626.6187, doi:10.1180/minmag.1980.043.329.13, S2CID 140671477

- ^ Fales 2008, pp. 520–522.

- ^ a b Fuccaro, Nelida (1995). Aspects of the social and political history of the Yazidi enclave of Jabal Sinjar (Iraq) under the British mandate, 1919-1932 (PDF). Durham University. pp. 22–3. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Haase 1997, p. 643.

- ^ a b Tim Lister (August 12, 2014). "Dehydration or massacre: Thousands caught in ISIS chokehold". CNN. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- ^ Fuccaro, Nelida (1999). The Other Kurds: Yazidis in Colonial Iraq. London: I.B.Tauris. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-1-86064-170-1.

- ^ Parry, Oswald Hutton (1895). Six Months in a Syrian Monastery: Being the Record of a Visit to the Head Quarters of the Syrian Church in Mesopotamia: With Some Account of the Yazidis Or Devil Worshippers of Mosul and El Jilwah, Their Sacred Book. London: H. Cox. p. 381. OCLC 3968331.

- ^ a b Savelzberg, Hajo & Dulz 2010, p. 101.

- ^ a b c d e f g Savelzberg, Hajo & Dulz 2010, p. 103.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, p. 89.

- ^ a b Savelzberg, Hajo & Dulz 2010, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Savelzberg, Hajo & Dulz 2010, pp. 105.

- ^ Martin Chulov (3 August 2014). "40,000 Iraqis stranded on mountain as Isis jihadists threaten death". The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ^ "Northern Iraq: UN voices concern about civilians' safety, need for humanitarian aid". United Nations News Centre. 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ^ "Irak : la ville de Sinjar tombe aux mains de l'Etat islamique". Le Monde (in French). 2014-08-03. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ^ a b "Thousands of Yazidis 'still trapped' on Iraq mountain". BBC News. 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ^ "People Eating Leaves to Survive on Shingal Mountain, Where Three More Die". Rûdaw.net. 2014-08-07. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ^ a b "Iraq crisis: No quick fix, Barack Obama warns". BBC News. 2014-08-09. Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- ^ "Britain's RAF makes second aid drop to Mount Sinjar Iraqis trapped by Isis – video". The Guardian. 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ^ "JTF633 supports Herc mercy dash". Media Release. Department of Defence. 22 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Irak : les opérations pour sauver les réfugiés yézidis continuent". Le Monde (in French). 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ^ Parkinson, Joe (18 August 2014). "Iraq Crisis: Kurds Push to Take Mosul Dam as U.S. Gains Controversial Guerrilla Ally". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b "Irak: les yazidis fuient les atrocités des djihadistes". Le Figaro (in French). 10 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-08-11.

- ^ Rubin, Alissa J.; Almukhtar, Sarah; Kakol, Kamil (April 2, 2018). "In Iraq, I Found Checkpoints as Endless as the Whims of Armed Men". The New York Times.

- ^ "Etat islamique en Irak : décapités, crucifiés ou exécutés, les yézidis sont massacrés par les djihadistes" (in French). Atlantico. 9 August 2014. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014.

- ^ Ahmed, Havidar (14 August 2014). "The Yezidi Exodus, Girls Raped by ISIS Jump to their Death on Mount Shingal". Rudaw Media Network. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Fales, Frederick Mario (2008), "Saggar", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2022-03-14

- Haase, C. P. (1997). "Sindjar". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 643–644. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Savelzberg, Eva; Hajo, Siamend; Dulz, Irene (July–December 2010). "Effectively Urbanized: Yezidis in the Collective Towns of Sheikhan and Sinjar". Études rurales (186): 101–116. doi:10.4000/etudesrurales.9253. JSTOR 41403604.

- Gaunt, David (2015). "The Complexity of the Assyrian Genocide". Genocide Studies International. 9 (1): 83–103. doi:10.3138/gsi.9.1.05. S2CID 129899863.

External links

[edit] Media related to Sinjar Mountains at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sinjar Mountains at Wikimedia Commons