Ink wash painting

| Ink wash painting | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Liang Kai (Chinese: 梁楷, 1140–1210), Drunken Celestial (Chinese: 潑墨仙人), ink on Xuan paper, 12th century, Southern Song (Chinese), National Palace Museum, Taipei | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 水墨畫 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 水墨画 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 수묵화 | ||||||

| Hanja | 水墨畫 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 1. 水墨画 2. 墨絵 | ||||||

| Hiragana | 1. すいぼくが 2. すみえ | ||||||

| |||||||

Ink wash painting (simplified Chinese: 水墨画; traditional Chinese: 水墨畫; pinyin: shuǐmòhuà); is a type of Chinese ink brush painting which uses washes of black ink, such as that used in East Asian calligraphy, in different concentrations. It emerged during the Tang dynasty of China (618–907), and overturned earlier, more realistic techniques. It is typically monochrome, using only shades of black, with a great emphasis on virtuoso brushwork and conveying the perceived "spirit" or "essence" of a subject over direct imitation.[1][2][3] Ink wash painting flourished from the Song dynasty in China (960–1279) onwards, as well as in Japan after it was introduced by Zen Buddhist monks in the 14th century.[4] Some Western scholars divide Chinese painting (including ink wash painting) into three periods: times of representation, times of expression, and historical Oriental art.[5][6] Chinese scholars have their own views which may be different; they believe that contemporary Chinese ink wash paintings are the pluralistic continuation of multiple historical traditions.[7]

In China, Japan and, to a lesser extent, Korea, ink wash painting formed a distinct stylistic tradition with a different set of artists working in it than from those in other types of painting. In China especially it was a gentlemanly occupation associated with poetry and calligraphy. It was often produced by the scholar-official or literati class, ideally illustrating their own poetry and producing the paintings as gifts for friends or patrons, rather than painting for payment.

In practice a talented painter often had an advantage in climbing the bureaucratic ladder. In Korea, painters were less segregated, and more willing to paint in two techniques, such as mixing areas of colour with monochrome ink, for example in painting the faces of figures.[1][3][8]

The vertical hanging scroll was the classic format; the long horizontal handscroll format tended to be associated with professional coloured painting, but was also used for literati painting. In both formats paintings were generally kept rolled up, and brought out for the owner to admire, often with a small group of friends.[9] Chinese collectors liked to stamp paintings with their seals and usually in red inkpad; sometimes they would add poems or notes of appreciation. Some old and famous paintings have become very disfigured by this; the Qianlong Emperor was a particular offender.[2]

In landscape painting the scenes depicted are typically imaginary or very loose adaptations of actual views. The shan shui style of mountain landscapes are by far the most common, often evoking particular areas traditionally famous for their beauty, from which the artist may have been very distant.[3][10]

Philosophy

[edit]

East Asian writing on aesthetics is generally consistent in saying that the goal of ink and wash painting is not simply to reproduce the appearance of the subject, but to capture its spirit. To paint a horse the ink-wash painting artist must understand its temperament better than its muscles and bones. To paint a flower there is no need to perfectly match its petals and colors, but it is essential to convey its liveliness and fragrance. It has been compared to the later Western movement of Impressionism.[1] It is also particularly associated with the Chán or Zen sect of Buddhism, which emphasizes "simplicity, spontaneity and self-expression", and Daoism, which emphasizes "spontaneity and harmony with nature,"[4] especially when compared with the less spiritually-oriented Confucianism.[3][11]

East Asian ink wash painting has long inspired modern artists in the West. In his classic book Composition, American artist and educator Arthur Wesley Dow (1857–1922) wrote this about ink wash painting: "The painter... put upon the paper the fewest possible lines and tones; just enough to cause form, texture and effect to be felt. Every brush-touch must be full-charged with meaning, and useless detail eliminated. Put together all the good points in such a method, and you have the qualities of the highest art".[12] Dow's fascination with ink wash painting not only shaped his own approach to art but also helped free many American modernists of the era, including his student Georgia O'Keeffe, from what he called a "story-telling" approach. Dow strived for harmonic compositions through three elements: line, shading, and color. He advocated practicing with East Asian brushes and ink to develop aesthetic acuity with line and shading.[3][13]

Technique, materials and tools

[edit]Ink wash painting uses tonality and shading achieved by varying the ink density, both by differential grinding of the ink stick in water and by varying the ink load and pressure within a single brushstroke. Ink wash painting artists spend years practicing basic brush strokes to refine their brush movement and ink flow. These skills are closely related to those needed for basic writing in East Asian characters, and then for calligraphy, which essentially use the same ink and brushes. In the hand of a master, a single stroke can produce considerable variations in tonality, from deep black to silvery gray. Thus, in its original context, shading means more than just dark-light arrangement: It is the basis for the nuance in tonality found in East Asian ink wash painting and brush-and-ink calligraphy.[14]

Once a stroke is painted it cannot be changed or erased. As a result, ink and wash painting is a technically demanding art form requiring great skill, concentration, and years of training.[13][2]

The Four Treasures is summarized in a four-word couplet: "文房四寶: 筆、墨、紙、硯," (Pinyin: wénfáng sìbǎo: bǐ, mò, zhǐ, yàn) "The four jewels of the study: Brush, Ink, Paper, Inkstone" by Chinese scholar-official or literati class, which are also indispensable tools and materials for East Asian painting.[15][16]

Brush

[edit]The earliest intact ink brush was found in 1954 in the tomb of a Chu citizen from the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) located in an archaeological dig site Zuo Gong Shan 15 near Changsha. This primitive version of an ink brush found had a wooden stalk and a bamboo tube securing the bundle of hair to the stalk. Legend wrongly credits the invention of the ink brush to the later Qin general Meng Tian.[14] Traces of a writing brush, however, were discovered on the Shang jades, and were suggested to be the grounds of the oracle bone script inscriptions.[17]

The writing brush entered a new stage of development in the Han dynasty. First, the decorative craft of engraving and inlaying on the pen-holder appeared. Second, some writings on the production of writing brush have also survived. For example, the first monograph on the selection, production and function of a writing brush was written by Cai Yong in the eastern Han dynasty. Third, the special form of "hairpin white pen" appeared. Officials in the Han dynasty often sharpened the end of the brush and stuck it in their hair or hat for their convenience. Worshipers also often put pen on their heads to show respect.[14][13]

During the Yuan and Ming dynasties, a group of pen making experts emerged in Huzhou. They included Wu Yunhui, Feng Yingke, Lu Wenbao, Zhang Tianxi, and others. Huzhou has been the center of Chinese brush making since the Qing dynasty. At the same time, many famous brushes were produced in other places, such as the Ruyang Liu brush in Henan province, the Li Dinghe brush in Shanghai, and the Wu Yunhui in Jiangxi province.[14]

Ink wash painting brushes are similar to the brushes used for calligraphy and are traditionally made from bamboo with goat, cattle, horse, sheep, rabbit, marten, badger, deer, boar and wolf hair. The brush hairs are tapered to a fine point, a feature vital to the style of wash paintings.[3][13]

Different brushes have different qualities. A small wolf-hair brush that is tapered to a fine point can deliver an even thin line of ink (much like a pen). A large wool brush (one variation called the 'big cloud') can hold a large volume of water and ink. When the big cloud brush rains down upon the paper, it delivers a graded swath of ink encompassing myriad shades of gray to black.[2][17]

Inkstick

[edit]Ink wash painting is usually done on rice paper (Chinese) or washi (Japanese paper) both of which are highly absorbent and unsized. Silk is also used in some forms of ink painting.[18] Many types of Xuan paper and washi do not lend themselves readily to a smooth wash the way watercolor paper does. Each brush stroke is visible, so any "wash" in the sense of Western style painting requires partially sized paper. Paper manufacturers today understand artists' demands for more versatile papers and work to produce kinds that are more flexible. If one uses traditional paper, the idea of an "ink wash" refers to a wet-on-wet technique, applying black ink to paper where a lighter ink has already been applied, or by quickly manipulating watery diluted ink once it has been applied to the paper by using a very large brush.[13]

In ink wash paintings, as in calligraphy, artists usually grind inkstick over an inkstone to obtain black ink, but prepared liquid inks (bokuju (墨汁) in Japanese) are also available. Most inksticks are made of soot from pine or oil combined with animal glue.[19] An artist puts a few drops of water on an inkstone and grinds the inkstick in a circular motion until a smooth, black ink of the desired concentration is made. Prepared liquid inks vary in viscosity, solubility, concentration, etc., but are in general more suitable for practicing Chinese calligraphy than executing paintings.[20] Inksticks themselves are sometimes ornately decorated with landscapes or flowers in bas-relief and some are highlighted with gold.[17][3]

Xuan paper

[edit]Paper (Chinese: traditional 紙, simplified 纸; Pinyin: ⓘ) was first developed in China in the first decade of 100 AD. Previous to its invention, bamboo slips and silks were used for writing material. Several methods of paper production developed over the centuries in China. However, the paper which was considered of highest value was that of the Jingxian in Anhui Province. Xuan paper features great tensile strength, smooth surface, pure and clean texture as well as a clean stroke; it has great resistance to crease, corrosion, moth, and mold. Xuan paper has a special ink penetration effect, which is not readily available in paper made in Western countries.[21][22] It was first mentioned in ancient Chinese books Notes of Past Famous Paintings and New Book of Tang. It was originally produced in the Tang dynasty in Jing County, which was under the jurisdiction of Xuan Prefecture (Xuanzhou), hence the name Xuan paper. During the Tang dynasty, the paper was often a mixture of hemp (the first fiber used for paper in China) and mulberry fiber.[22]

The materials used in Xuan paper are closely related to the geographical environment of Jingxian. The bark of the Pteroceltis tatarinowii, a common variety of elm, is used as the main material for the production of rice paper in this area. Rice and several other materials were later added to the recipe in the Song and Yuan Dynasties. In those dynasties bamboo and mulberry began to be used to produce rice paper as well.[22][21]

The production of Xuan paper is about an eighteen-step process – taken in detail over a hundred steps may be counted. Some paper makers keep their process strictly secret. The process includes cooking and bleaching the bark of Pteroceltis tatarinowii and adding various fruit juices.[22][21]

Inkstone

[edit]The inkstone is not only a traditional Chinese stationery device, but also an important tool of ink painting. It is a stone mortar used for the grinding and containment of ink. In addition to stones, inkstones can be made of clay, bronze, iron and porcelain. This device evolved from the friction tool used to rub dyes about six to seven thousand years ago.[23]

-

Ink brush with golden dragon design, used by the Ming Wanli Emperor (1563–1620), China.

-

Reconstruction of Emperor Qianlong's (1711–1799) writing table, China.

-

Murata Seimin (1761–1837), Brush rest in the shape of a praying mantis, circa 1800 (late Edo), Medium: bronze, Dimensions: 18 cm (7 in), Japan. Collected By the Walters Art Museum.

-

Commemorative Chinese inksticks for collectors.

-

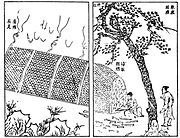

Image from the 17th-century technical document Tiangong Kaiwu (天工開物-松烟制墨法) detailing how pine is burned in a furnace at one end and its soot collected at the other for making inkstick, China.

-

Fragment of ancient Chinese paper map with features in black ink, found on the chest of the occupant of Tomb 5 of Fangmatan, Gansu in China in 1986, from early Western Han, 2nd century BC, 5.6 cm × 2.6 cm (2.2 in × 1.0 in).

-

An image of a Ming dynasty woodcut describing five major steps in ancient Chinese papermaking process as outlined by Cai Lun in 105 AD. The image is from the 17th-century technical document Tiangong Kaiwu (天工開物-覆簾壓紙), China.

-

A Duan Inkstone of the Song dynasty-In for making Chinese ink using water and an inkstick, 10th century, China.

-

East Asian painting-calligraphy's ink stone, ink stick, and usage.

History and artists

[edit]Chinese painters and their influence on East Asia

[edit]In Chinese painting, brush painting was one of the "four arts" expected to be learnt by China's class of scholar-officials.[4] Ink wash painting appeared during the Tang dynasty (618–907), and its early development is credited to Wang Wei (active in the 8th century) and Zhang Zao, among others.[3] In the Ming dynasty, Dong Qichang would identify two distinct styles: a clearer, grander Northern School 北宗画 or 北画; Beizonghua or Beihua, Japanese: Hokushūga or Hokuga), and a freer, more expressive Southern School (南宗画 or 南画; Nanzonghua or Nanhua, Japanese: Nanshūga or Nanga), also called "Literati Painting" (文人画; Wenrenhua, Japanese: Bunjinga).[1][13][24][25]

Tang, Song and Yuan dynasties

[edit]Western scholars have written that before the Song dynasty, ink wash was primarily used for representation painting, while in the Yuan dynasty, expressive painting predominated.[5][6] Chinese historical views have traditionally found it more appropriate to divide the general artistic features of this historical stage by the theory of Southern School and Northern School, as promulgated Dong Qichang in the Ming dynasty.[7][8][26]: 236

Southern School and painters

[edit]Southern School (南宗画; nán zōng huà) of Chinese painting, often called "literati painting" (文人画; wén rén huà), is a term used to denote art and artists which stand in opposition to the formal Northern School of painting. Representing painters are Wang Wei, Dong Yuan, and so on. The Southern School has had a profound impact on Japanese and Southeast Asian paintings.[27] Wang Wei (王維; 699–759), Zhang Zao (张璪 or 张藻) and Dong Yuan (董源; Dǒng Yuán; Tung Yüan, Gan: dung3 ngion4; c. 934–962) are important representatives of early Chinese ink wash painting of the Southern School. Wang Wei was a Chinese poet, musician, painter, and politician during the Tang dynasty, 8th century. Wang Wei is the most important representative of early Chinese ink wash painting. He believed that in all forms of painting, ink wash painting is the most advanced.[11][28] Zhang Zao was a Chinese painter, painting theorist and politician during the Tang dynasty, 8th century.[29] He created the method of using fingers instead of brush to draw ink wash painting.[7] Dong Yuan was a Chinese painter during the Five Dynasties (10th century). His ink wash painting style is considered by Dong Qichang to be the most typical style of Southern School.[26]: 599

Chinese ink wash painters such as Li Cheng (李成; Lǐ Chéng; Li Ch'eng; 919–967), Courtesy name Xiánxī (咸熙), Fan Kuan (范寬; Fàn Kuān; Fan K'uan, c. 960–1030), courtesy name "Zhongli" and "Zhongzheng", better known by his pseudonym "Fan Kuan" and Guo Xi (郭熙; Guō Xī; Kuo Hsi) (c. 1020–1090) had a great influence on East Asian ink wash painting. Li Cheng was a Chinese painter of the Song dynasty. He was influenced by Jing Hao, Juran. Li Cheng has a profound impact on Japanese and Korean painters.[30][31] Fan Kuan was a Chinese landscape painter of the Song dynasty. He has a profound impact on Japanese and Korean paintings.[32][33][34] Guoxi was a Chinese landscape painter from Henan Province who lived during the Northern Song dynasty.[35][36] One text entitled "The Lofty Message of Forest and Streams" (Linquan Gaozhi 林泉高致) is attributed to him.[37]

As representatives of scholar painting (or "Literati Painting", the part of the Southern School),[38] painters such as Su Shi, Mi Fu and Mi Youren, especially Muqi, had a decisive influence on East Asian ink wash painting. Su Shi (蘇軾; 苏轼; 8 January 1037 – 24 August 1101), courtesy name Zizhan (Chinese: 子瞻), art name Dongpo (Chinese: 東坡), was a Chinese poet, writer, politician, calligrapher, painter, pharmacologist, and gastronome of the Song dynasty.[39] Mi Fu (米芾 or 米黻; Mǐ Fú, also given as Mi Fei, 1051–1107)[40] was a Chinese painter, poet, and calligrapher born in Taiyuan during the Song dynasty.[41] Mi Youren (米友仁, 1074–1153) was a Chinese painter, poet, and calligrapher born in Taiyuan during the Song dynasty. He was the eldest son of Mi Fu.[42] Muqi (牧谿; Japanese: Mokkei; 1210?–1269?), also known as Fachang (法常), was a Chinese Chan Buddhist monk and painter who lived in the 13th century, around the end of the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). Today, he is considered to be one of the greatest Chan painters in history. His ink paintings, such as the Daitoku-ji triptych and Six Persimmons are regarded as essential Chan paintings.[43] Muqi's style of painting has also profoundly impacted painters from later periods to follow, especially monk painters in Japan.[44][45]

Four Masters of the Yuan dynasty (元四家; Yuán Sì Jiā) is a name used to collectively describe the four Chinese painters Huang Gongwang (Chinese: 黄公望, 1269–1354), Wu Zhen (Chinese: 吳鎮, 1280–1354), Ni Zan (Chinese: 倪瓚; 1301–1374), and Wang Meng (王蒙, Wáng Méng; Zi: Shūmíng 叔明, Hao: Xiāngguāng Jūshì 香光居士) (c. 1308–1385), who were active during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). They were revered during the Ming dynasty and later periods as major exponents of the tradition of "literati painting" (wenrenhua), which was concerned more with individual expression and learning than with outward representation and immediate visual appeal.[46] Other notable painters from the Yuan period include Gao Kegong (高克恭; 髙克恭; Gaō Kègōng; Kao K'o-kung; 1248–1310), also a poet, and was known for his landscapes,[47] and Fang Congyi.

-

Dong Yuan (934–962) Dongtian Mountain Hall (洞天山堂圖), ink and light color on silk, 10th century, the Five Dynasties (Chinese). National Palace Museum, Taipei.

-

Dong Yuan, Jiangnan Summer View, ink and light color on silk, 10th century, the Five Dynasties, China. Liaoning Provincial Museum.

-

Li Cheng (李成; Lǐ Chéng; Li Ch'eng; 919–967), A Solitary Temple Amid Clearing Peaks (晴峦萧寺), ink and light color on silk. 111.76 cm × 55.88 cm (44.00 in × 22.00 in). 11th century, China. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

Fan Kuan (范寬; Fàn Kuān; Fan K'uan, c. 960–1030), Travellers among Mountains and Streams (谿山行旅圖), ink and slight color on silk, dimensions of 6.75 ft × 2.5 ft (2.06 m × 0.76 m). 11th century, China.[32] National Palace Museum, Taipei[33]

-

Guo Xi (郭熙; Guō Xī; Kuo Hsi) (c. 1020–1090), Early Spring, signed and dated 1072, ink and light lolor on silk. 11th century, China. Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk. National Palace Museum, Taipei.

-

Guo Xi, Ping Yuan Tu (窠石平遠圖), 1078, ink and light lolor on silk, China. Collected by the Palace Museum, Beijing.

-

Guo Xi, Clearing Autumn Skies over Mountains and Valleys, ink and light lolor on silk, China. Northern Song dynasty c. 1070, detail from a horizontal scroll.[48]

-

Muqi, Guanyin, Crane, and Gibbons, Southern Song (Chinese), 13th century, set of three hanging scrolls, ink and color on silk, height: 173.9–174.2 cm (68.5–68.6 in), collected in Daitokuji, Kyoto, Japan. Designated National Treasure.

-

Gao Kegong (1248–1310), Evening Clouds (Chinese: 秋山暮靄圖), ink and color on Xuan paper mounted on hanging scroll, 13th century, China. Collected by the Palace Museum, Beijing.

-

Huang Gongwang (Chinese: 黄公望, 1269-1354), Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, Chinese: 富春山居圖, ink on Xuan paper, 1348 and 1351, collected by National Palace Museum, Taipei.

-

Huang Gongwang, Stone Cliff at the Pond of Heaven, 1341, ink and light lolor on silk, China. Collected by Palace Museum, Beijing.

-

Ni Zan (Chinese: 倪瓚; 1301–1374), Six Gentlemen (Chinese: 六君子圖), ink on Xuan paper mounted on hanging scroll, dimensions: W 33.3 cm, H 61.9 cm, 1345, China. Collected by Shanghai Museum.

-

Ni Zan, Enjoying the Wilderness in an Autumn Grove (Chinese: 秋林野興圖), medium: hanging scroll; ink on Xuan paper, dimensions: 38 5/8 × 27 1/8 in. (98.1 × 68.9 cm), 1339, China. Collected by Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Northern School and painters

[edit]Northern School (北宗画; běi zōng huà) was a manner of Chinese landscape painting centered on a loose group of artists who worked and lived in Northern China during the Five Dynasties period that occupied the time between the collapse of the Tang dynasty and the rise of the Song. Representing painters are Ma Yuan, Xia Gui, and so on. The style stands in opposition to the Southern School (南宗画; nán zōng huà) of Chinese painting. Northern School has a profound impact on Japanese and Southeast Asian paintings.[49]

Li Tang (Chinese: 李唐; pinyin: Lǐ Táng; Wade–Giles: Li T'ang, courtesy name Xigu (Chinese: 晞古); c. 1050 – 1130) of the Northern School, especially Ma Yuan (馬遠; Mǎ Yuǎn; Ma Yüan; c. 1160–65 – 1225) and Xia Gui's ink wash painting modeling and techniques have a profound influence on Japanese and Korean ink wash paintings. Li Tang was a Chinese landscape painter who practised at Kaifeng and Hangzhou during the Song dynasty. He forms a link between earlier painters such as Guo Xi, Fan Kuan and Li Cheng and later artists such as Xia Gui and Ma Yuan. He perfected the technique of "axe-cut" brush-strokes.[26]: 635 Ma Yuan was a Chinese painter of the Song dynasty. His works, together with that of Xia Gui, formed the basis of the so-called Ma-Xia (馬夏) school of painting, and are considered among the finest from the period. His works has inspired both Chinese artists of the Zhe School, as well as the great early Japanese painters Shūbun and Sesshū.[50] Xia Gui (夏圭 or 夏珪; Hsia Kui; fl. 1195–1225), courtesy name Yuyu (禹玉), was a Chinese landscape painter of the Song dynasty. Very little is known about his life, and only a few of his works survive, but he is generally considered one of China's greatest artists. He continued the tradition of Li Tang, further simplifying the earlier Song style to achieve a more immediate, striking effect. Together with Ma Yuan, he founded the so-called Ma-Xia (馬夏) school, one of the most important of the period. Although Xia was popular during his lifetime, his reputation suffered after his death, together with that of all Southern Song academy painters. Nevertheless, a few artists, including the Japanese master Sesshū, continued Xia's tradition for hundreds of years, until the early 17th century.[51]

Liang Kai (梁楷; Liáng Kǎi; c. 1140–1210) was a Chinese painter of the Southern Song dynasty. He was also known as "Madman Liang" because of his very informal pictures. His ink wash painting style has a huge influence on East Asia, especially Japan.[52] Yan Hui (颜辉; 顏輝; Yán Huī; Yen Hui); was a late 13th century Chinese painter who lived during the Southern Song and early Yuan dynasties. Yan Hui's style of painting has also profoundly impacted the painters in Japan.[53]

-

Li Tang (Chinese: 李唐; pinyin: Lǐ Táng; Wade–Giles: Li T'ang, 1050 – 1130), Wind in Pines Among a Myriad Valleys, Chinese: 萬壑松風圖, 1124, ink and color on silk, 188.7 cm (74.2 in); Width: 139.8 cm (55 in), collected by National Palace Museum, Taipei.

-

Li Tang, Duke Wen of Jin Recovering His State, handscroll, ink and color on silk, collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Li Tang, Boy and water buffalo, collected by the Palace Museum, Beijing.

-

Liang Kai (梁楷, 1140–1210), Shakyamuni Emerging from the Mountains, 出山釋迦圖, Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 117.6 cm × 51.9 cm (46.3 in × 20.4 in), collected by Tokyo National Museum. File:Ma Yuan - Dancing and Singing- Peasants Returning from Work.jpg

-

Xia Gui (夏圭 or 夏珪; Hsia Kui; fl. 1195–1225), Sailboat in Rainstorm, Chinese: 風雨行舟圖, ink and light colors on silk, 23.9 × 25.1 cm (9.4 × 9.8 in), 13th century China. Collected by Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

-

Yan Hui (颜辉; 顏輝; Yán Huī; Yen Hui), Shi De (拾得), ink and light color on silk, 13th century, Yuan dynasty (Chinese). Tokyo National Museum.

Ming and Qing dynasties

[edit]Four Masters of the Ming dynasty (明四家; Míng Sì Jiā) are a traditional grouping in Chinese art history of four famous Chinese painters of the Ming dynasty. The group are Shen Zhou (Chinese: 沈周, 1427–1509), Wen Zhengming (Chinese: 文徵明, 1470–1559), both of the Wu School, Tang Yin (Chinese: 唐寅, 1470–1523), and Qiu Ying (Chinese: 仇英, c. 1494–1552). They were approximate contemporaries, with Shen Zhou the teacher of Wen Zhengming, while the other two studied with Zhou Chen. Their styles and subject matter were varied.[54]

Xu Wei (徐渭; Xú Wèi; Hsü Wei, 1521–1593) and Chen Chun (陳淳; 1483–1544) are the main painters of the bold and unconstrained style of literati painting, and their ink wash painting is characterized by the incisive and fluent ink and wash. Their ink wash painting style is considered to have the typical characteristics of the Historical Oriental art.[5] Xu Wei, other department "Qingteng Shanren" (青藤山人; Qīngténg Shānrén), was a Ming dynasty Chinese painter, poet, writer and dramatist famed for his artistic expressiveness.[55] Chen Chun was a Ming dynasty artist. Born into a wealthy family of scholar-officials in Suzhou, he learned calligraphy from Wen Zhengming, one of the Four Masters of the Ming dynasty. Chén Chún later broke with Wen to favor a more freestyle method of ink wash painting.[56]

Dong Qichang (Chinese: 董其昌; pinyin: Dǒng Qíchāng; Wade–Giles: Tung Ch'i-ch'ang; 1555–1636) of the Ming dynasty and the Four Wangs (四王; Sì Wáng; Ssŭ Wang) of the Qing dynasty are representative painters of retro-style ink wash paintings that imitated the painting style before the Yuan dynasty. Dong Qichang was a Chinese painter, calligrapher, politician, and art theorist of the later period of the Ming dynasty. He is the founder of the theory of Southern School and Northern School in ink wash painting. His theoretical system has a great influence on the painting concept and practice of East Asian countries, including Japan and Korea.[26]: 703 [7] Four Wangs were four Chinese landscape painters in the 17th century, all called Wang (surname Wang). They are best known for their accomplishments in shan shui painting.They were Wang Shimin (1592–1680), Wang Jian (1598–1677), Wang Hui (1632–1717) and Wang Yuanqi (1642–1715).[26]: 757

Bada Shanren (朱耷; zhū dā, born "Zhu Da"; c. 1626–1705), Shitao (石涛; 石濤; Shí Tāo; Shih-t'ao; other department "Yuan Ji" (原濟; 原济; Yuán Jì), 1642–1707) and Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou (扬州八怪; 揚州八怪; Yángzhoū Bā Guài) are the innovative masters of ink wash painting in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties.[57][58] Bada Shanren, other department "Bada Shanren" (八大山人; bā dà shān rén), was a Han Chinese painter of ink wash painting and a calligrapher. He was of royal descent, being a direct offspring of the Ming dynasty prince Zhu Quan who had a feudal establishment in Nanchang. Art historians have named him as a brilliant painter of the period.[59][60] Shitao, born into the Ming dynasty imperial clan as "Zhu Ruoji" (朱若極), was one Chinese landscape painter in early Qing dynasty (1644–1912).[61] Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou is the name for a group of eight Chinese painters active in the 18th century, who were known in the Qing dynasty for rejecting the orthodox ideas about painting in favor of a style deemed expressive and individualist.[26]: 668

Xu Gu (虚谷; 虛谷; Xū Gǔ; Hsü Ku, 1824–1896) was a Chinese monk painter and poet during the Qing dynasty.[62] His ink wash paintings give the audience a sense of abstraction and illusion.[63]

-

Shen Zhou (Chinese: 沈周, 1427–1509), Lofty Mount Lu (Chinese: 廬山高), Ming dynasty, 1467 (明 成化丁亥), Medium: Hanging scroll, ink and colors on Xuan paper, Dimensions: 193.8 × 98.1 cm (height × width), China. Collected by National Palace Museum.

-

Dong Qichang (Chinese: 董其昌; pinyin: Dǒng Qíchāng; Wade–Giles: Tung Ch'i-ch'ang; 1555–1636), Wanluan Thatched Hall, Chinese: 婉孌草堂圖, 1597, hanging scroll, ink on Xuan paper, Ming dynasty, China.

-

Zhu Da (Chinese: 朱耷, 1626–1705), Lotus and Birds, ink on Xuan paper, 17th century, Qing dynasty, China, Shanghai Museum.

-

Shitao (石涛; 石濤; Shí Tāo; Shih-t'ao, 1642–1707), Pine Pavilion Near a Spring, ink on Xuan paper, 1675, China. The collection of the Shanghai Museum.

-

Shitao, Searching for Immortals, ink and light color on paper, 17th century, China. The collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

Huang Shen (Chinese: 黃慎, 1687–1772) (one of the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou), Fisherman and Fisherwoman, ink on Xuan paper, 18th century, Qing dynasty, China, collection of the Nanjing Museum.

Modern times

[edit]Modern and contemporary Chinese freehand ink wash painting is the most famous of the Shanghai School, and the most representative ones are the following painters. Wu Changshuo (吳昌碩; Wú Chāngshuò 12 September 1844 – 29 November 1927, also romanised as Wu Changshi, 吳昌石; Wú Chāngshí), born Wu Junqing (吳俊卿; Wú Jùnqīng), was a prominent painter, calligrapher and seal artist of the late Qing period. He is the leader of the Shanghai School. Wu Changshuo's style of painting has profoundly impacted the paintings in Japan.[64] Pu Hua (蒲华; 蒲華; Pú Huá; P'u Hua; c. 1834–1911) was a Chinese landscape painter and calligrapher during the Qing dynasty. His style name was 'Zuo Ying'. Pu painted landscapes and ink bamboo in an unconventional style of free and easy brush strokes. He is one of the important representatives of the Shanghai School.[65] Wang Zhen (王震; Wang Chen; 1867–1938),[66] commonly known by his courtesy name Wang Yiting (王一亭; Wang I-t'ing), was a prominent businessman and celebrated modern Chinese artist of the Shanghai School. Qi Baishi (齐白石; 齊白石; qí bái shí, 齐璜; 齊璜; qí huáng 1 January 1864 – 16 September 1957) was a Chinese painter noted for the whimsical, often playful style of his ink wash painting works.[67] Huang Binhong (黃賓虹; Huáng Bīnhóng; 1865–1955) was a Chinese literati painter and art historian born in Jinhua, Zhejiang province. His ancestral home was She County, Anhui province. He was the grandson of artist Huang Fengliu. He would later be associated with Shanghai and finally Hangzhou. He is considered one of the last innovators in the literati style of painting and is noted for his freehand landscapes.[55]: 2056

Important painters who have absorbed Western sketching methods to improve Chinese ink wash painting include Gao Jianfu, Xu Beihong and Liu Haisu, etc.[26]: 1328 Gao Jianfu (1879–1951; 高剑父, pronounced "Gou Gim Fu" in Cantonese) was a Chinese painter and social activist. He is known for leading the Lingnan School's effort to modernize Chinese traditional ink wash painting as a "new national art."[68][69] Xu Beihong (徐悲鴻; Hsü Pei-hung; 19 July 1895 – 26 September 1953), also known as "Ju Péon", was a Chinese painter.[70] He was primarily known for his Chinese ink paintings of horses and birds and was one of the first Chinese artists to articulate the need for artistic expressions that reflected a modern China at the beginning of the 20th century. He was also regarded as one of the first to create monumental oil paintings with epic Chinese themes – a show of his high proficiency in an essential Western art technique.[71] He was one of the four pioneers of Chinese modern art who earned the title of "The Four Great Academy Presidents".[72] Liu Haisu (刘海粟; Liú Hǎisù; 16 March 1896 – 7 August 1994) was a prominent 20th century Chinese painter and a noted art educator. He excelled in Chinese painting and oil painting. He was one of the four pioneers of Chinese modern art who earned the title of "The Four Great Academy Presidents".[72]

Pan Tianshou, Zhang Daqian and Fu Baoshi are important ink wash painters who stick to the tradition of Chinese classical Literati Painting.[72] Pan Tianshou (潘天寿; 潘天壽; Pān Tiānshòu; 1897–1971) was a Chinese painter and art educator. Pan was born in Guanzhuang, Ninghai County, Zhejiang Province, and graduated from Zhejiang First Normal School (now Hangzhou High School). He studied Chinese traditional painting with Wu Changshuo. Later he created his own ink wash painting style and built the foundation of Chinese traditional painting education. He was persecuted during the Cultural Revolution until his death in 1971.[73] Zhang Daqian (張大千; Chang Ta-ch'ien; 10 May 1899 – 2 April 1983) was one of the best-known and most prodigious Chinese artists of the 20th century. Originally known as a guohua (traditionalist) painter, by the 1960s he was also renowned as a modern impressionist and expressionist painter. In addition, he is regarded as one of the most gifted master forgers of the 20th century.[74] Fu Baoshi (傅抱石; Fù Bàoshí; 1904–1965), was a Chinese painter. He also taught in the Art Department of Central University (now Nanjing University). His works of landscape painting employed skillful use of dots and inking methods, creating a new technique encompassing many varieties within traditional rules.[75]

Shi Lu (石鲁; 石魯; Shí Lǔ; 1919–1982), born "Feng Yaheng" (冯亚珩; 馮亞珩; Féng Yàhéng), was a Chinese painter, wood block printer, poet and calligrapher. He based his pseudonym on two artists who greatly influenced him, the landscape painter Shitao and writer Lu Xun. He created two different ink wash painting styles.[76]

-

QiBaishi, Eagle Standing on Pine Tree, Four-character Couplet in Seal Script, Chinese: 松柏高立圖·篆書四言聯, ink on Xuan paper, 266 × 100 cm (104.7 × 39.3 in), 1946, Modern times, China.

-

Chen Shizeng (Chinese: 陳師曾, 1876–1923), Ganoderma and Rock, Chinese: 芝石圖, ink and color on Xuan paper, Modern times, China.

-

Gao Jianfu (Chinese: 高劍父, 1879–1951), Fire on the Eastern Battlefield, Chinese: 東戰場的烈焰, ink and color on Xuan paper, 1930s, 166 x 92 cm. Lingnan School of Painting in Guangzhou Museum of Art, China.

Other countries in East Asia

[edit]Since the Tang dynasty, Japan, Korea, and East Asian countries have extensively studied Chinese painting and ink wash painting.[8][25] Josetsu (Chinese: 如拙) who immigrated to Japan from China has been called the "Father of Japanese ink painting".[77] East Asian styles have mainly developed from the painting styles of Southern School and Northern School.[8][3][78]

Korea

[edit]Ink wash painting was most likely brought to Korea during the Goryeo dynasty, although no confirmed examples are extant; a number of works preserved in Japanese Buddhist temples are possibly by Korean authors, but this is limited to speculation.[79] Nonetheless, it would continue to develop as a major genre of Korean painting in the following Joseon dynasty as well.

In Korea, the Dohwaseo or court academy was very important, and most major painters came from it, although the emphasis of the academy was on realistic decorative works and official portraits, so something of a break from this was required.[80] However the high official and painter Gang Se-hwang and others championed amateur literati or seonbi painting in the Chinese sensibility. Many painters made both Chinese-style landscapes and genre paintings of everyday life, and there was a tradition of more realistic landscapes of real locations, as well as mountains as fantastical as any Chinese paintings, for which the Taebaek Mountains along the eastern side of Korea offered plenty of inspiration.[81]

An Kyŏn was a painter of the early Joseon period. He was born in Jigok, Seosan, South Chungcheong Province. He entered royal service as a member of the Dohwaseo, the official painters of the Joseon court, and drew Mongyu dowondo (몽유도원도) for Prince Anpyeong in 1447 which is currently stored at Tenri University. This piece is the oldest surviving Korean piece for which the author and date of composition are known.[79] He was deeply influenced by the Southern School (Chinese: 南宗画; pinyin: nán zōng huà) of Chinese painting, especially Li Cheng and Guo Xi.[82]

Byeon Sang-byeok, member of the Miryang Byeon clan, was active during the latter half of the Joseon period (1392–1910). Byeon is famous for his precise depictions of animals and people in detailed brushwork. Byeon was deeply influenced by the Court Painting (Chinese: 院體畫; pinyin: Yuàn Tǐ Huà) of Chinese painting,[83] especially Huang Quan.[84][85]

The Korean painters influenced by the Northern School in the Song dynasty include Kang Hŭian, Kim Hong-do, Jang Seung-eop and so on. Kang Hŭian (1417?–1464), pen name Injae 인재, was a prominent scholar and painter of the early Joseon period. He was good at poetry, calligraphy, and painting. He entered royal service by passing gwageo in 1441 under the reign of king Sejong (1397–1418–1450).[86][87] Kim Hong-do (김홍도, born 1745, died 1806?–1814?), also known as "Kim Hong-do", most often styled "Danwon" (단원), was a full-time painter of the Joseon period of Korea. He was together a pillar of the establishment and a key figure of the new trends of his time, the 'true view painting'. Gim Hong-do was an exceptional artist in every field of traditional painting. His ink wash paintings of figures are deeply influenced by the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou. Jang Seung-eop (1843–1897) (commonly known by his pen name "Owon") was a painter of the late Joseon dynasty in Korea. His life was dramatized in the award-winning 2002 film Chi-hwa-seon directed by Im Kwon-taek. He was also one of few painters to hold a position of rank in the Joseon court.[88][89]

Jeong Seon (Korean: 정선) (1676–1759) was a landscape painter, also known by his pen name "Kyomjae" ("humble study"), who is counted among the most famous Korean painters.[90] His style was realistic rather than abstract,[91] and he additionally is credited with advancing the ink-wash artform towards a more uniquely Korean direction.[79] His works include ink and oriental water paintings, such as Inwangjesaekdo (1751), Geumgang jeondo (1734), and Ingokjeongsa (1742), as well as numerous "true-view" landscape paintings (진경산수화) on the subject of Korea and the history of its culture. This latter style, which was a subgenre of the shan-shui genre, was most prominent between the mid-18th century and mid-19th century, and was pursued by several other painters as well. Moreover, this style spread to Japan through Choe Buk and Kim Yu-seong as part of diplomatic missions to Japan, where it was sometimes known as "New Joseon Shan-shui painting" (新朝鮮山水畫), and influenced Ike no Taiga and Uragami Gyokudō.[92]

Japan

[edit]In Japan, the style was introduced in the 14th century, during the Muromachi period (1333–1573) through Zen Buddhist monasteries,[93] and in particular Josetsu, a painter who immigrated from China and taught the first major early painter Tenshō Shūbun (d. c. 1450). Both he and his pupil Sesshū Tōyō (1420–1506) were monks, although Sesshū eventually left the clergy, and spent a year or so in China in 1468–69.[94] By the end of the period the style had been adopted by several professional or commercial artists, especially from the large Kanō school founded by Kanō Masanobu (1434–1530); his son Kanō Motonobu was also very important. In the Japanese way, the most promising pupils married daughters of the family, and changed their names to Kanō. The school continued to paint in the traditional Japanese yamato-e and other coloured styles as well.[24][2]

A Japanese innovation of the Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568–1600) was to use the monochrome style on a much larger scale in byōbu folding screens, often produced in sets so that they ran all round even large rooms. The Shōrin-zu byōbu of about 1595 is a famous example; only some 15% of the paper is painted.[95]

Josetsu (如拙, fl. 1405–1496) was one of the first suiboku (ink wash) style Zen Japanese painters in the Muromachi period (15th century). He was probably also a teacher of Tenshō Shūbun at the Shōkoku-ji monastery in Kyoto. A Chinese immigrant, he was naturalised in 1470 and is known as the "Father of Japanese ink painting".[77]

Kanō school, a Japanese ink wash painting genre, was born under the significant influence of Chinese Taoism and Buddhist culture.[78] Kanō Masanobu (狩野 元信, 1434? – August 2, 1530?, Kyoto) was the leader of Kano school, laid the foundation for the school's dominant position in Japanese mainstream painting for centuries. He was mainly influenced by Xia Gui (active in 1195–1225), a Chinese court painter of the Southern Song dynasty.[96] He was the chief painter of the Ashikaga shogunate and is generally considered the founder of the Kanō school of painting. Kano Masanobu specialized in Zen paintings as well as elaborate paintings of Buddhist deities and Bodhisattvas.[97] Tenshō Shūbun (天章 周文, died c. 1444–50) was a Japanese Zen Buddhist monk and painter of the Muromachi period. He was deeply influenced by the Northern School (北宗画; běi zōng huà) of Chinese painting and Josetsu.[98] Sesshū Tōyō (Japanese: 雪舟 等楊; Oda Tōyō since 1431, also known as Tōyō, Unkoku, or Bikeisai; 1420 – 26 August 1506) was the most prominent Japanese master of ink and wash painting from the middle Muromachi period. He was deeply influenced by the Northern School (北宗画; běi zōng huà) of Chinese painting, especially Ma Yuan and Xia Gui.[99] After studying landscape painting in China, he drew "秋冬山水図". This painting was drawn the landscape of Song dynasty in China. He painted the natural landscape of winter. The feature of this painting is the thick line that represents the cliff.

Sesson Shukei (雪村 周継, 1504–1589) and Hasegawa Tōhaku (長谷川 等伯, 1539 – 19 March 1610) mainly imitated the ink wash painting styles of the Chinese Song dynasty monk painter Muqi.[5] Sesson Shukei was one of the main representatives of Japanese ink wash painting, a learned and prolific Zen monk painter. He studied a wide range of early Chinese ink wash painting styles and played an important role in the development of Japanese Zen ink wash painting. Colleagues of Chinese ink painter Muqi (active in 13th century) first brought Muxi painting to Japan in the late 13th century. Japanese Zen monks follow and learn the gibbon pictures painted by Chinese monk painter Muqi. By the late 15th century, the animal image of Muqi style had become a hot topic in large-scale Japanese painting projects.[100]

The smaller, more purist and less flamboyant Hasegawa school was founded by Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539–1610), and lasted until the 18th century. The nanga (meaning "Southern painting") or bunjinga ("literati") style or school ran from the 18th century until the death of Tomioka Tessai (1837–1924) who was widely regarded as the last of the nanga artists.[13][24] Hasegawa Tōhaku was a Japanese painter and founder of the Hasegawa school. He is considered one of the great painters of the Azuchi–Momoyama period (1573–1603), and he is best known for his byōbu folding screens, such as Pine Trees and Pine Tree and Flowering Plants (both registered National Treasures), or the paintings in walls and sliding doors at Chishaku-in, attributed to him and his son (also National Treasures). He was deeply influenced by Chinese painting of the Song dynasty, especially Liang Kai and Muqi.[101][102]

The ink wash paintings of Mi Fu and his son had a profound influence on Japanese ink painters, and Ike no Taiga is one of them.[78] Ike no Taiga (池大雅, 1723–1776) was a Japanese painter and calligrapher born in Kyoto during the Edo period. Together with Yosa Buson, he perfected the bunjinga (or nanga) genre. The majority of his works reflected his passion for classical Chinese culture and painting techniques, though he also incorporated revolutionary and modern techniques into his otherwise very traditional paintings. As a bunjin (文人, literati, man of letters), Ike was close to many of the prominent social and artistic circles in Kyoto, and in other parts of the country, throughout his lifetime.[25]

-

Josetsu (A Chinese immigrant, "Father of Japanese ink wash painting"),[77] Catching catfish with a gourd (瓢鮎図, Hyōnen-zu), ink on paper, 111.5 cm × 75.8 cm (43.9 in × 29.8 in), 1415, Japan.

-

Kanō Masanobu, The Four Accomplishments, ink and light lolor on silk, 67 in. × 12 ft. 6 in. (170.2 × 381 cm), mid-16th century, Japan. Collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[96]

-

Ahn Gyeon, Late Winter (만동), ink on silk, 15th century. Korea.

-

Kang Hŭian, Scholar gazing at the running river, ink on silk, Gosagwansudo, 15th century. Korea.

-

Sesshū Tōyō (1420–1506), Autumn Landscape (Shūkei-sansui), ink on silk, Japan.

-

Sesshū, Landscape, Mountain landscapes are by far the most common scenes depicted in ink wash landscape paintings, Japan.[8]

-

Sesson Shūkei (雪村 周継), Gibbons in a Landscape, ink on Xuan paper, 62 in. x 11 ft. 5 in. (157.5 x 348 cm), 1570, Japan. Collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[100]

-

Ike no Taiga, Fishing in Springtime, ink and light color on silk, 1747, Japan. Collected by Cleveland Museum of Art.

-

Ike no Taiga, Orchids, between 1723 and 1776, ink on Xuan paper, Japan. Collected by Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

Jang Seung-eop, Double Eagle, ink on Xuan paper, 19th century, Korea.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]This article has an unclear citation style. (June 2023) |

- ^ a b c d Gu, Sharron (22 December 2011). A Cultural History of the Chinese Language. McFarland. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0-7864-8827-8. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Yilong, Lu (30 December 2015). The History and Spirit of Chinese Art (2-Volume Set). Enrich Professional Publishing Limited. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-62320-130-2. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i The Editorial Committee of Chinese Civilization: A Source Book, City University of Hong Kong (1 April 2007). China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization. City University of HK Press. pp. 732–5. ISBN 978-962-937-140-1. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Perkins, Dorothy (19 November 2013). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Routledge. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-135-93562-7. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d Loehr, Max (1970). The Period and Content of Chinese Painting-Collection of Essays from the International Symposium on Chinese Painting. Taipei: National Palace Museum. pp. 186–192 and 285–297.

- ^ a b Cahill, James (1990). "Methodology of Chinese Painting History" 中國繪畫史方法論. New Arts (1). Hangzhou: Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts.

- ^ a b c d Zhiying, Hu (2007). New Literature-Reconstructing the Framework of a Poetic Art Theory and Its Significance. Zhengzhou: Elephant Publisher House. pp. 184–202. ISBN 9787534747816.

- ^ a b c d e Fong, Wen C. (2003). "Why Chinese Painting Is History?". The Art Bulletin. 85 (2): 258–280. doi:10.2307/3177344. JSTOR 3177344. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Jenyns, 177-118

- ^ Jenyns, 152–158

- ^ a b Cahill, James (2006). "Meaning and Function of Chinese Landscape Painting". Arts Exploration (20). Nanning: Guangxi Art College.

- ^ Dow, Arthur Wesley (1899). Composition.

- ^ a b c d e f g Watson, William, Style in the Arts of China, 1974, Penguin, p. 86-88, ISBN 0140218637

- ^ a b c d Kwo, Da-Wei (October 1990). Chinese brushwork in calligraphy and painting : its history, aesthetics, and techniques (Dover ed.). Mineola, N.Y. ISBN 0486264815. OCLC 21875564.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Chinesetoday.com. "Chinesetoday.com Archived 16 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine." 趣談「文房四寶」. Retrieved on 2010-11-27.

- ^ Big5.xinhuanet.com. "Big5.xinhuanet.com Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine." 走近文房四寶. Retrieved on 2010-11-27.

- ^ a b c Cambridge History of Ancient China, 1999:108–112

- ^ Jenyns, 120–122

- ^ Jenyns, 123

- ^ Okamoto, Naomi The Art of Sumi-e: Beautiful ink painting using Japanese Brushwork, Search Press, Kent UK, 2015, p. 16

- ^ a b c "Introduction to the Xuan Paper Making in Anhui China". China Culture Tour.com. 2019. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d Fei Wen Tsai; Dianne van der Reyden, Technology, treatment, and care of a chinese wood block print (PDF), Smithsonian Institution, p. 4, archived (PDF) from the original on 2 July 2021, retrieved 26 July 2021 originally appeared as "Analysis of modern Chinese paper and treatment of a Chinese woodblock print" in The Paper Conservator, 1997, pp. 48–62

- ^ Chen, Tingyou (3 March 2011). Chinese Calligraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-18645-2. Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Kleiner, Fred S. (5 January 2009). Gardner's Art through the Ages: Non-Western Perspectives. Cengage Learning. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-495-57367-8. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Meccarelli, Marco (December 2015). "Chinese Painters in Nagasaki: Style and Artistic Contaminatio during the Tokugawa Period (1603–1868) (Ming Qing Studies)". Asia Orientale. 18. Aracne: 175–236. Archived from the original on 6 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cihai Editorial Committee (辭海編輯委員會) (1979). Cihai(辭海). Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House(上海辭書出版社). ISBN 9787532600618. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Sickman, 334

- ^ Bio dates: Ch'en and Bullock, 49 and 53; Stimson, 22; Watson, 10 and 170; and Wu, 225. Note, however, other sources, such as Chang, 58, and Davis, x, give his years as 701–761

- ^ "Zhang Zao". Boya Renwu. Archived from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "Chinese painting – Five Dynasties (907–960) and Ten Kingdoms (902–978)". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Fu, Mi; Ji, Zhao; Jing, Cai. Xuan He HuaPu(宣和画谱). OCLC 1122878721. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 162.

- ^ a b Liu, 50.

- ^ Schirokauer, Conrad; Brown, Miranda; Lurie, David; Gay, Suzanne (1 January 2012). A Brief History of Chinese and Japanese Civilizations. Cengage Learning. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-495-91322-1. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ Barnhart: Page 372. Guo Xi's style name was Chunfu (淳夫)

- ^ Ci hai: Page 452

- ^ Hearn, Maxwell K. Cultivated Landscapes: Chinese Paintings from the Collection of Marie-Hélène and Guy Weill. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press, 2002.

- ^ "Scholar's Painting". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Murck, Alfreda (2000). Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. Harvard University Asia Center. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-674-00782-6. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Barnhart: 373. His courtesy name was Yuanzhang (元章) with several sobriquets: Nangong (南宮), Lumen Jushi (鹿門居士), Xiangyang Manshi (襄陽漫士), and Haiyue Waishi (海岳外史)

- ^ "米芾的書畫世界 The Calligraphic World of Mi Fu's Art". Taipei: National Palace Museum. 2006. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013.

- ^ "Mi Youren". Boya Renwu. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Lachman, Charles (2005). "Art". In Lopez, Donald S. (ed.). Critical terms for the study of Buddhism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 4~5. ISBN 9780226493237. OCLC 270606633.

- ^ Rio, Aaron (2015). Ink painting in medieval kamakura. pp. 67~113.

- ^ Little, Stephen; Eichman, Shawn; Shipper, Kristofer; Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1 January 2000). Taoism and the Arts of China. University of California Press. p. [1]. ISBN 978-0-520-22785-9.

- ^ Farrer, 115–116; 339–340

- ^ "Gao Kegong". Boya Renwu. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Sickman, 219–220

- ^ Barnhart, "Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting", 93.

- ^ Little, Stephen; Eichman, Shawn; Shipper, Kristofer; Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1 January 2000). Taoism and the Arts of China. University of California Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-520-22785-9.

- ^ Barnhart, "Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting", 96.

- ^ Shen, Zhiyu (1981). The Shanghai Museum of Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. pp. 223–224. ISBN 0-8109-1646-0.

- ^ "Yan Hui". Boya Renwu. Archived from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Rawson, p. 340

- ^ a b Cihai: Page 802.

- ^ "CHEN CHUN". British Museum. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Birds in a Lotus Pond". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Thirty-six Peaks of Mount Huang Recollected". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Glaze, Anna. Landscapes, Tradition, and the Seventeenth-Century Art Market: A Different Side of Bada Shanren. Master's Thesis, University of California, Davis., June, 2008.

- ^ China: five thousand years of history and civilization. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press. 2007. p. 761. ISBN 978-962-937-140-1. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ Hay 2001, pp. 1, 84

- ^ "Xū Gǔ Brief Biography". Archived from the original on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ^ "Squirrel on an Autumn Branch". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Wu Changshuo". Boya Renwu. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "Pu Hua-Artworks, Biography". Artnet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Chinese Artists (Zhongguo meishu jia renming cidian) on p. 131

- ^ "Qi Baishi-Biography-Artworks". Artnet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "The Lingnan School Painting". The Lingnan School of Painting: Art and Revolution in Modern China. 2014. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Gao Minglu, and Norman Bryson. Inside Out: New Chinese Art. San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1998, page 26.

- ^ 毕楠. "Five major works of Xu Beihong that shouldn't be missed – Chinadaily.com.cn". China Daily. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ "Singapore Art Museum (SAM) opens 'Xu Beihong in Nanyang' a Solo Exhibition". Art Knowledge News. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ a b c Zhang Shaoxia and Li Xiaoshan(张少侠 and 李小山) (1986). History of Contemporary Chinese Painting (中国现代绘画史). Nanjing: Jiangsu Fine Arts Publishing House(江苏美术出版社). pp. 6–7. OCLC 23317610. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ King, Richard; Croizier, Ralph; Zheng, Shentian; Watson, Scott, eds. (2010). Art in Turmoil: The Chinese Cultural Revolution, 1966–76. University of British Columbia Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0774815437. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Zhu, Haoyun (2012). "Zhang Daqian: A World-renowned Artist". China and the World Cultural Exchange. 12: 18–23. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Fu Baoshi-Biography-Artworks". Artnet. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Hawkins (2010), p. 62.

- ^ a b c "Taiko Josetsu". Britannica article. Archived from the original on 16 May 2005.

- ^ a b c Stephen Francis Salel. "Retracting a Diagnosis of Madness: A Reconsideration of Japanese Eccentric Art". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ a b c "수묵화 (水墨畵)", 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture] (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 18 November 2024

- ^ Dunn, 361–363

- ^ Dunn, 367–368

- ^ "An Kyŏn". Towooart. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Court Painting". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 21 June 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Sŏng-mi, Yi (2008). "Euigwe and the Documentation of Joseon Court Ritual Life". Archives of Asian Art (in Korean). 58: 113–133. doi:10.1353/aaa.0.0003. ISSN 1944-6497. S2CID 201782649. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ 國手 [Guksu] (in Korean). Nate Korean-Hanja Dictionary. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ (in Korean) "Humanism in Gang Hui-an's Paintings". ARTne. 2002. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Brief biography". 엠파스홈 (in Korean). Archived from the original on 4 May 2007.

- ^ Turner 2003, p. (18)53

- ^ Choi Yongbeom (최용범), Reading Korean history in one night (하룻밤에 읽는 한국사) p299, Paper Road, Seoul, 2007. ISBN 89-958266-3-0.

- ^ "Gyeomjae Jeong seon Memorial Museum, Korea". asemus. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Ah-young, Chung (15 September 2009). "Jeong Seon's Paintings Brought to Life". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Hong, Seon-pyo, "진경산수화 (眞景山水畵)", 한국민족문화대백과사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean Culture] (in Korean), Academy of Korean Studies, retrieved 18 November 2024

- ^ Stanley-Baker, 118–124

- ^ Stanley-Baker, 126–129

- ^ Stanley-Baker, 132–134, 148–50

- ^ a b "The Four Accomplishments". New York: The Metropolitain Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". Archived from the original on 19 December 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Shūbun" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 889, p. 8890, at Google Books

- ^ Appert, Georges. (1888). Ancien Japon, p. 80. Archived 13 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Gibbons in a Landscape". New York: The Metropolitain Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Suiboku-ga." Archived 5 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 10 Dec. 2009

- ^ HASEGAWA Tohaku (1539–1610) Archived 2009-12-08 at the Wayback Machine Mibura-Dera Temple Website. 10 Dec 2009

References

[edit]- Cihai Editorial Committee (辭海編輯委員會), Cihai, , Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House (上海辭書出版社), 1979. ISBN 9787532600618

- Dunn, Michael, The Art of East Asia, ed. Gabriele Fahr-Becker, Könemann, Volume 2, 1998. ISBN 3829017456

- Farrer, Anne, in Rawson, Jessica (ed). The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, British Museum Press, 2007 (2nd edn). ISBN 9780714124469

- Hay, Jonathan (2001). Shitao: Painting and Modernity in Early Qing China. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521393423.

- Hawkins, Shelley Drake (2010). King, Richard; Zheng, Sheng Tian; Watson, Scott (eds.). Summoning Confucius: Inside Shi Lu's Imagination. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. pp. 58–90. ISBN 9789888028641.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - Jenyns, Soame, A Background to Chinese Painting (with a Preface for Collectors by W. W. Winkworth), 1935, Sidgwick & Jackson, Ltd.

- Little, Stephen; Eichman, Shawn; Shipper, Kristofer; Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, Taoism and the Arts of China, University of California Press, 2000-01-01. ISBN 978-0-520-22785-9

- Loehr, Max, The Great Painters of China, Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1980. ISBN 0714820083

- Rawson, Jessica (ed). The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, British Museum Press, 2007 (2nd edn). ISBN 9780714124469

- Sickman, Laurence, in: Sickman L. & Soper A., The Art and Architecture of China, Pelican History of Art, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), 3rd ed 1971. LOC 70-125675

- Stanley-Baker, Joan, Japanese Art, Thames and Hudson, World of Art, 2000 (2nd edn). ISBN 0500203261

- Turner, Jane (2003). Grove Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 32600. ISBN 978-0-1951-7068-9.

![Fan Kuan (范寬; Fàn Kuān; Fan K'uan, c. 960–1030), Travellers among Mountains and Streams (谿山行旅圖), ink and slight color on silk, dimensions of 6.75 ft × 2.5 ft (2.06 m × 0.76 m). 11th century, China.[32] National Palace Museum, Taipei[33]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/Fan_Kuan_-_Travelers_Among_Mountains_and_Streams_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/99px-Fan_Kuan_-_Travelers_Among_Mountains_and_Streams_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg?auto=webp)

![Guo Xi, Clearing Autumn Skies over Mountains and Valleys, ink and light lolor on silk, China. Northern Song dynasty c. 1070, detail from a horizontal scroll.[48]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/37/Kuo_Hsi_001.jpg/180px-Kuo_Hsi_001.jpg?auto=webp)

![Josetsu (A Chinese immigrant, "Father of Japanese ink wash painting"),[77] Catching catfish with a gourd (瓢鮎図, Hyōnen-zu), ink on paper, 111.5 cm × 75.8 cm (43.9 in × 29.8 in), 1415, Japan.](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fb/Hy%C3%B4nen_zu_by_Josetsu.jpg/180px-Hy%C3%B4nen_zu_by_Josetsu.jpg?auto=webp)

![Kanō Masanobu, The Four Accomplishments, ink and light lolor on silk, 67 in. × 12 ft. 6 in. (170.2 × 381 cm), mid-16th century, Japan. Collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[96]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/Kano_Motonobu_%E7%8B%A9%E9%87%8E%E5%85%83%E4%BF%A1%2C_The_Four_Accomplishments%2C_mid-16th_century.jpg/180px-Kano_Motonobu_%E7%8B%A9%E9%87%8E%E5%85%83%E4%BF%A1%2C_The_Four_Accomplishments%2C_mid-16th_century.jpg?auto=webp)

![Sesshū, Landscape, Mountain landscapes are by far the most common scenes depicted in ink wash landscape paintings, Japan.[8]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/32/Landscape_by_Sesshu_%28Ohara%29.jpg/58px-Landscape_by_Sesshu_%28Ohara%29.jpg?auto=webp)

![Sesson Shūkei (雪村 周継), Gibbons in a Landscape, ink on Xuan paper, 62 in. x 11 ft. 5 in. (157.5 x 348 cm), 1570, Japan. Collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[100]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c6/Sesson_Sh%C5%ABkei_%E9%9B%AA%E6%9D%91%E5%91%A8%E7%B6%99%2C_Gibbons_in_a_Landscape%2C_1570.jpg/180px-Sesson_Sh%C5%ABkei_%E9%9B%AA%E6%9D%91%E5%91%A8%E7%B6%99%2C_Gibbons_in_a_Landscape%2C_1570.jpg?auto=webp)