Shahbag

Shahbagh

শাহবাগ থানা | |

|---|---|

Shahabagh Thana (police station) Main Entrance | |

| |

| Coordinates: 23°44.3′N 90°23.75′E / 23.7383°N 90.39583°E | |

| Municipality | Dhaka |

| Area | |

• Total | 17.4 km2 (6.7 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Total | 63,761 |

| • Density | 3,700/km2 (9,500/sq mi) |

| Postal code | 1000 |

| Area code | 02[2] |

| Website | www |

Shahbagh (also Shahbaugh or Shahbag, Bengali: শাহবাগ, romanized: Shāhbāg, IPA: [ˈɕaɦ.baɡ]) is a major neighbourhood and a police precinct or thana in Dhaka, the capital and largest city of Bangladesh. It is also a major public transport hub.[3] It is a junction between two contrasting sections of the city—Old Dhaka and New Dhaka—which lie, respectively, to its south and north. Developed in the 17th century during Mughal rule in Bengal, when Old Dhaka was the provincial capital and a centre of the flourishing muslin industry, it came to neglect and decay in early 19th century. In the mid-19th century, the Shahbagh area was developed as New Dhaka became a provincial centre of the British Raj, ending a century of decline brought on by the passing of Mughal rule.

Shahbagh is the location of the nation's leading educational and public institutions, including the University of Dhaka, the oldest and largest public university in Bangladesh, Dhaka Medical College, the largest medical college in the country, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU), and the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, the largest public university for technological studies in the country. Shahbagh hosts many street markets and bazaars. Since Bangladesh achieved independence in 1971, the Shahbagh area has become a venue for celebrating major festivals, such as the Bengali New Year and Basanta Utsab.

Shahbagh's numerous ponds, palaces and gardens have inspired the work of writers, singers, and poets. With Dhaka University at its centre, the thana has been the origin of major political movements in the nation's 20th century history, including the All India Muslim Education Conference in 1905, which led to the All India Muslim League. In 1947, to both the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan; the Bengali Language Movement in 1952, which led to the recognition of Bengali as an official language of Pakistan; and the Six point movement in 1966, which led to the nation's independence. It was here, on 7 March 1971, that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman delivered a historic speech calling for the independence of Bangladesh from Pakistan, and here too, later that year, that the Pakistani Army surrendered in the Liberation War of Bangladesh. The area has since become a staging ground for protests by students and other groups. It was the site of public protests by around 30,000 civilians on 8 February 2013, against a lenient ruling against war criminals.[4][5][6]

Etymology

[edit]The neighborhood was originally named Bagh-e-Badshahi (Persian for Garden of Kings), but later came to be called by the shortened name Shah (Persian:شاه, king) Bagh (Persian: باغ, garden).[7]

History

[edit]

Although urban settlements in the Dhaka area date back to the seventh century CE,[8] the earliest evidence of urban construction in the Shahbagh area is to be found at monuments constructed after 1610, when the Mughals turned Dhaka into a provincial capital and established the gardens of Shahbag. Among these monuments are: the Dhaka Gate, located near the Bangla Academy in Shahbag, and erected by Mir Jumla, the Mughal subadar of Bengal from 1660 to 1663;[9] the Mariam Saleha Mosque, a three-domed Mughal-style mosque in Nilkhet-Babupara, constructed in 1706;[10] the Musa Khan Mosque on the western side of Dhaka University, likely constructed in the late 17th century;[11] and the Khwaja Shahbaz's Mosque-Tomb,[12] located behind the Dhaka High Court and built in 1679 by Khwaja Shahbaz, a merchant-prince of Dhaka during the vice-royalty of Prince Muhammad Azam, the son of Mughal Emperor Aurengzeb.[13] According to legends a sadhu named Gopal Giri, from Badri Narayan, established a Kali temple in Shahbagh in the 13th century. Called kaathgarh at the time, it eventually became the Ramna Kali Mandir.[14] Iti s also said that Kedar Rai of Bikrampur, one of the Baro-Bhuyans, apparently built a Kali temple on the site in the late 16th century, and the main temple was built by Haricharan Giri in the early 17th century.[14]

However, with the decline of Mughal power in Bengal, the Shahbagh gardens—the Gardens of the Kings—fell into neglect. In 1704, when the provincial capital was moved to Murshidabad, they became the property of the Naib Nazims – the Deputy-Governors of the sub-province of East Bengal – and the representatives of the Nawabs of Murshidabad.[citation needed] Although British power was established in Dacca in 1757, the upkeep of Shahbag gardens was resumed only in the early 19th century under the patronage of an East India Company judge, Griffith Cook,[15][failed verification] and P. Aratun.[16] In 1830, the Ramna area, which included Shahbag, was incorporated into Dhaka city consequent to the deliberations of the Dacca Committee (for the development of Dacca town) founded by district collector Henry Walters.[17] A decade later, Nawab Khwaja Alimullah, founder of the Dhaka Nawab Family and father of Nawab Bahadur Sir Khwaja Abdul Ghani, purchased the Shahbagh zamindari (estate) from the East India Company. Upon his death, in 1868, the estate passed to his grandson Nawab Bahadur Sir Khwaja Ahsanullah. In the early 20th century, Ahsanullah's son, Nawab Bahadur Sir Khwaja Salimullah, was able to reclaim some of the lost splendour of the gardens by dividing them into two smaller gardens—the present-day Shahbagh and Paribagh (or, "garden of fairies")—the latter named after Paribanu, one of Ahsanullah's daughters.

With the partition of Bengal in 1905, and with Dacca becoming the capital of the new province of East Bengal, European-style houses were rapidly built in the area, especially along the newly constructed Fuller Road (named after Sir Bampfylde Fuller, the first Lieutenant Governor of East Bengal). Around this time, the first zoo in the Dhaka area was also established in Shahbag.[18] Rani Bilasmani of Bhawal established a new idol in the Kali temple and excavated a large pond in front of it during this period.[14] In 1924, Anandamayi Ma moved into Shabag and established Anandamayi Asharam inside the 2.22 acres of temple ground.[14]

After the creation of the new nation of Pakistan in 1947, when Dhaka became the capital of East Pakistan, many new buildings were built in the Shahbag area, including, in 1960, the office of Bangladesh Betar,[19] (then Pakistan Radio), the national radio station, the (now-defunct) Dacca race-course, as well as the second electric power-plant in East Bengal. On 7 March 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman chose the Ramna Racecourse near Shahbagh to deliver his speech calling for an independent Bangladesh. On 27 March 1971, Pakistani Army destroyed the Kali temple and its 120 feet tower.[14] During the ensuing Bangladesh Liberation War, many foreign journalists, including the Associated Press bureau chief in Pakistan, Arnold Zeitlin, and Washington Post reporter, H.D.S. Greenway stayed at Hotel InterContinental (now Hotel Sheraton) at the Shahbagh Intersection. The hotel, which had been declared a neutral zone,[20][21][22] nonetheless came under fire from both combatants in the war—the Mukti Bahini and Pakistani army.[23][24] At the conclusion of the war, the Hotel Intercontinental was at first chosen as the venue for the surrender ceremony of the West Pakistan Army;[23] however, the final surrender ceremony later took place in the nearby Ramna Park (now Suhrawardy Uddan).

Shahbagh is part of the 181st electoral district of Bangladesh: Dhaka 8.[25] In 2008 Bangladeshi general election Rashed Khan Menon of Workers Party of Bangladesh was elected as the member of Jatiyo Sangsad (member of parliament or MP) from the area. In the Dhaka City Corporation ward commissioner election of 2002 Md. Chowdhury Alam (ward 56) and Khaja Habibullah Habib (ward 57) were elected from the Shahbagh area.[26]

More than 1,000 people gathered here on 5 February 2013, growing to 20,000 people by 9 February,[27] following the conviction of Abdul Quader Mollah for war crimes by the Bangladesh International Crimes Tribunal, and his sentence to life imprisonment. Protesters thought he should have received the death sentence for his crimes, as had two other political leaders who were convicted.[28][29] The protest movement gathered force, as leaders also called for the banning of Jamaat-e-Islami from politics, as two of its top leaders had been convicted of war crimes and followers had conducted violent protests and riots. The 2013 Shahbag protests have influenced national politics, and has been called 'Projonmo Chattar'.[30]

Urban layout

[edit]| Landmarks |

|---|

| BSMMU | BIRDEM |

| Hotel Sheraton | Faculty of Fine Arts |

| Bangladesh National Museum |

| Central Public Library |

| University Mosque and Cemetery | IBA, DU |

| Dhaka Club | Shishu Park |

| Tennis Federation | Police Control Room |

With an area of 4.2 square kilometres (1.6 sq mi) and an estimated 2006 population of 112,000[31] Shabag lies within the monsoon climate zone at an elevation of 1.5 to 13 metres (5 to 43 ft) above mean sea level.[32] Like rest of Dhaka city it has an annual average temperature of 25 °C (77 °F) and monthly means varying between 18 °C (64 °F) in January and 29 °C (84 °F) in August. Nearly 80% of the annual average rainfall of 1,854 mm (73 in) occurs between May and September.[33]

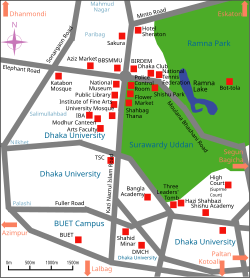

The Shahbagh neighbourhood covers a large approximately rectangular area, extending on the east from Ramna Park to the Supreme Court of Bangladesh; on the west as far as Sonargaon Road; on the south as far as Fuller Road and from the University of Dhaka[34] to the Suhrawardy Udyan (formerly, Ramna Racecourse); and on the north as far as Minto Road, Hotel Sheraton and the Diabetic Hospital.

Shahbagh is home to the Dhaka Metropolitan Police (DMP) Control Room as well as a Dhaka Electric Supply Authority substation. The Mausoleum of three leaders Bengali statesman A.K. Fazlul Huq (1873–1962), former Prime Minister of Pakistan, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (1892–1963), and former Prime Minister and Governor-General of Pakistan, Khwaja Nazimuddin (1894–1964)—are all located in Shahbag. The major academic bodies around Shahbag Intersection and in Shahbagh Thana area include: University of Dhaka, Dhaka Medical College, BUET, Bangladesh Civil Service Administration Academy, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU),[35] the only public medical university in the country, Institute of Cost & Management Accountants, IBA, Institute of Modern Languages, Udayan School, University Laboratory School, and the Engineering University School. Other public and educational institutions in the area include the Bangladesh National Museum, the Central Public Library, and the Shishu Academy, the National Academy for Children.

The Shahbagh Intersection, the nerve centre of the neighbourhood, is the location of many Dhaka landmarks. Well-known ones include Hotel Sheraton[36] (formerly Hotel Intercontinental, the second five-star hotel in Dhaka); the Dhaka Club, the oldest and largest club in Dhaka, established in 1911; the National Tennis Complex; Shishu Park, the oldest children's entertainment park in Dhaka, notable for admitting underprivileged children gratis on weekends; Sakura, the first bar in Dhaka; and Peacock, the first Dhaka bar with outdoor seating. The Shahbagh Intersection is one of the major public transportation hubs in Dhaka, along with Farmgate, Gulistan, Mohakhali, and Maghbazar.

The thana also contains a hospitals complex, which is a major destination for Bangladeshis seeking medical treatment. The Diabetic Association of Bangladesh (DAB[37]) is located at the Shahbag Intersection, as are BIRDEM (Bangladesh Institute of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders) and the BIRDEM Hospital. Flanking BIRDEM hospital is the Ibrahim Memorial Cardiac Hospital, named after Dr Muhammad Ibrahim, the founder of DAB and BIRDEM. Other facilities in the area are BSMMU Hospital (at the Intersection) and the Dhaka Medical College Hospital at the southern end of Shahbagh.

Located at the juncture of two major bus routes – Gulistan to Mirpur and Motijheel to Uttara – Shahbagh Intersection serves as a public transport hubs in Dhaka, where the population commutes exclusively by the city bus services.[38][39] The Shahbagh intersection hosts the Shahbagh metro station of MRT Line 6, which offers a safe, reliable and fast method of transportation to other parts of the city, compared to other vehicles. The metro station of Shahbagh sits in the route of Uttara (north) to Motijheel and Kamalapur and is located between Kawran Bazar and University of Dhaka metro rail stations. The Intersection also has one of the few taxi stands in Dhaka. The thoroughfares of Shahbag has been made free of cycle-rickshaws, the traditional transport of Dhaka.[40]

Shahbagh Square, also known as Shahbagh Circle, is a major road intersection and public transport hub located in Shahbagh thana. The intersection connects some of the important areas of Dhaka such as Gulshan, and Farmgate. It is also surrounded by some significant landmarks including Bangladesh National Museum, Suhrawardy Udyan, and Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University.[41] Throughout its history, Shahbag square has been a place of protests and demonstrations, most notably the 2013 Shahbagh protests.[42]

Historic mansions

[edit]Also located in Shahbagh are several mansions built by Dhaka Nawab Family in the 19th century. These mansions not only figured prominently in the history of Dhaka, but also gained mention in the histories of both Bengal and British India.

A well-known Nawab family mansion is the Ishrat Manzil. Originally, a dance-hall for the performances of Baijees, or dancing women, (including, among the famous ones, Piyari Bai, Heera Bai, Wamu Bai and Abedi Bai), the mansion became the venue for the All-India Muslim Education Society Conference in 1906, which was attended by 4,000 participants. In 1912, Society convened here again under the leadership of Nawab Salimullah, and met with Lord Hardinge, the Viceroy of India. The Ishrat Manzil was subsequently rebuilt as Hotel Shahbagh (designed by British architects Edward Hicks and Ronald McConnel), the first major international hotel in Dhaka. In 1965, the building was acquired by the Institute of Post-graduate Medicine and Research (IPGMR), and later, in 1998, by the Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU).[43]

Another Nawab mansion is the Jalsaghar. Built as a skating rink and a ballroom for the Nawabs, it was later converted into an eatery and meeting place for students and faculty of Dhaka University and renamed Madhur Canteen. In the late 1960s, Madhur Canteen became a focal point for planning student protests against the West Pakistan regime. Flanked on one side by the Dhaka University's Faculty of Fine Arts and on the other by the Institute of Business Administration (IBA), the Madhur Canteen remains a powerful political symbol.[43][44]

Nishat Manjil was built as the princely stable and clubhouse for the Nawabs, and served as a venue of receptions for the statesmen of the day, including Lord Dufferin (Viceroy of India), Lord Carmichael (Governor of Bengal), Sir Steuart Bayley (Lt. Governor of Bengal), Sir Charles Alfred Elliott (Lt. Governor of Bengal), and John Woodburn (Lt. Governor of Bengal).

The Nawab's Paribagh House was built by Khwaja Salimullah in the memory of his sister, Pari Banu. Later, with the downturn in the family's fortunes, his son, Nawab Khwaja Habibullah, lived here for many years. The hammam (bath) and the hawakhana (green house) were regarded as marvels of design in the early 20th century.[45]

Sujatpur Palace, the oldest Nawab mansion in the area, later became the residence for the Governor of East Bengal during the Pakistani Regime, and was subsequently turned into the Bangla Academy, the Supreme Bengali Language Authority in Bangladesh. Some of the palace grounds was handed over to the TSC (Teacher Student Center[46]) of Dhaka University, and became a major cultural and political meeting place in the 1970s.

Culture

[edit]

Shahbagh is populated by mostly teachers and students, and its civic life is dominated by the activities of its academic institutions. Its commercial life too reflects its occupants' intellectual and cultural pursuits. Among its best known markets is the country's largest second-hand, rare, and antiquarian book-market,[47] consisting of Nilkhet-Babupura Hawkers Market, a street market, and Aziz Supermarket, an indoor bazaar.[48] Shahbag is also home to the largest flower market (a street side open air bazaar) in the country, which is located at Shahbag Intersection,[49][50] as well as the largest pet market in the country, the Katabon Market.[51] In addition, Elephant Road features a large shoe market and, Nilkhet-Babupura, a large market for bedding accessories.

Shahbagh's numerous ponds, palaces and gardens have inspired the work of artists, including poet Buddhadeva Bose, singer Protiva Bose, writer-chronicler Hakim Habibur Rahman, and two Urdu poets of 19th-century Dhaka, Obaidullah Suhrawardy and Abdul Gafoor Nassakh.[52] Shahbag was at the centre of the cultural and political activities associated with the Language movement of 1952, which resulted in the founding here of the Bangla Academy, a national academy for promoting the Bengali language. The first formal art school in Dhaka – the Dhaka Art College[citation needed] (now Faculty of Fine Arts) – was founded in Shahbag by Zainul Abedin in 1948.[citation needed] The art college building, constructed in 1953–1954, was designed by Mazharul Islam, the pioneer of modern architecture in Bangladesh.[53] In the 1970s, Aftabuddin Ahmed and M. M. Yacoob opened Jiraz Art Gallery in the Shahbag area.[54][55] Other cultural landmarks in the area include the Bangladesh National Museum,[56] the National Public Library, and the Dhaka University Mosque and Cemetery, containing the graves of Kazi Nazrul Islam, the national poet, of painters Zainul Abedin and Quamrul Hassan, and of the teachers killed by Pakistani forces during the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

The Shahbagh area has a rich religious history. In the late 1920s, Sri Anandamoyi Ma, the noted Hindu ascetic, also known as the Mother of Shahbagh, built her ashram near Ramna Kali Mandir, or the Temple of Kali, at Ramna. Her presence in Dhaka owed directly to Shahbagh, for her husband, Ramani Mohan Chakrabarti, had accepted the position of caretaker of Shahbagh gardens a few years earlier. In 1971 the Temple of Kali was destroyed by the Pakistani Army in the Liberation War of Bangladesh.[57] A well-known local Muslim saint of the early 20th century was Syed Abdur Rahim, supervisor of the dairy farm established by Khwaja Salimullah, the Nawab of Dhaka, at Paribag. Known as the Shah Shahib of Paribag, Abdur Rahim had his khanqah (Persian: خانگاه, spiritual retreat) here; his tomb lies at the same location today.[58] Katabon Mosque, an important centre for Muslim missionaries in Bangladesh, is located in Shahbag as well. In addition, the only Sikh Gurdwara in Dhaka stands next to the Institute of Modern Languages in Shahbagh.[59]

Since 1875, the Shahbagh gardens have hosted a famous fair celebrating the Gregorian New Year and containing exhibits of agricultural and industrial items, as well as those of animals and birds. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the gardens were the private property of the Nawab of Dhaka, and, although a portion of the gardens had been donated to Dhaka University in 1918, ordinary citizens could enter the main gardens only during the fair. In 1921, at the request of the Nawab's daughter, Paribanu, the organisers of the fair set aside one day during which only women were admitted to the fair, a tradition that has continued down to the present. Today, the fair features dance recitals by girls, Jatra (a native form of folk theater), putul naach (puppet shows), magic shows and Bioscope shows. Historically, Shahbagh was also the main venue in Dhaka for other recreational sports like Boli Khela (wrestling) and horse racing.[43]

The Basanta Utsab (Festival of Spring) takes place every 14 February—the first day of spring, according to the reformed Bangladeshi calendar. Basanta Utsab has become a major festival in Dhaka since it was first celebrated in Shahbagh in the 1960s.[60][61][62] Face painting, wearing yellow clothes (signifying Spring), music, and local fairs are typical of the many activities associated with the festival, which often also includes themes associated with Valentine's Day.

Shahbagh is also a focal point of the Pohela Baishakh (the Bengali New Year) festival, celebrated every 14 April following the revised Bengali Calendar, and now the biggest carnival in Dhaka.[63][64] From 1965 to 1971 the citizens of Dhaka observed the festival as a day of protest against the Pakistani regime.[65] Other local traditions associated with the festival include the Boishakhi Rally and the Boishakhi Mela begun by the Institute of Fine Arts (now Faculty of Fine Arts) and the Bangla Academy respectively. In addition, Chayanaut Music School began the tradition of singing at dawn under the Ramna Batamul (Ramna Banyan tree). In 2001, a suicide bomber killed 10 people and injured 50 others during the Pohela Baishakh festivals. The Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami, an Islamic militant group, was alleged to be behind the incident.[66]

Books and movies figure prominently in the cultural life of Shahbagh. The biggest book fair in Bangladesh is held every February on the premises of the Bangla Academy in Shahbagh. The only internationally recognised film festival[67] in Bangladesh—the Short and Independent Film Festival, Bangladesh—takes place every year at the National Public Library premises. The organisers of the film festival, the Bangladesh Short Film Forum, have their offices in Aziz Market. Aparajeyo Bangla, a sculpture in memory of Bangladesh Liberation War, is also in Shahbagh.

Demographics

[edit]According to 2011 Census of Bangladesh, Shahbagh Thana has a population of 68,140 with average household size of 7.8 members, and an average literacy rate of 84.7% vs national average of 51.8% literacy.[68]

Notes

[edit]- ^ National Report (PDF). Population and Housing Census 2022. Vol. 1. Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. November 2023. p. 386. ISBN 978-9844752016.

- ^ "Bangladesh Area Code". China: Chahaoba.com. 18 October 2024.

- ^ Nawazish, Mohammed (17 September 2003). "Bus Menace in Dhaka Streets". The Bangladesh Observer. Archived from the original on 21 March 2005. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ Khan, Mubin S. (2 August 2002). "Eight days that shook the campus". Weekly Holiday. Archived from the original on 13 February 2005. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ^ "DU students on rampage: Student injured in road accident". The Independent. Dhaka. 10 May 2006. Archived from the original on 14 July 2006. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ^ "Environmentalists for steps to limit green house gas, global warming". New Age. Dhaka. 12 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ^ "Dhaka City under the Mughals, Bangladesh". Dhaka City Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ Jatindramohan Rai quotes Rajtarangini by Kalhan in Dhakar Itihas, 1913

- ^ Juberee, Abdullah (11 March 2006). "Dhaka Gate at DU stands unnoticed". New Age. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- ^ Bari, MA (2012). "Mariam Saleha Mosque". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Bari, MA (2012). "Musa Khan Mosque". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Bari, MA (2012). "Khwaja Shahbaz's Mosque and Tomb". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Syed Aulad, Hasan (1912). Notes on the Antiquities of Dacca. Dhaka: M.M. Bysak. pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c d e Nessa, Fazilatun (2012). "Ramna Kali Mandir". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Ahmed, Sharif Uddin (1986). Dacca: A Study in Urban History and Development (1st ed.). London: Curzon Press. p. 131. ISBN 0-913215-14-7.

Upon [Judge John Francis Griffith Cooke's] retirement, in 1844 or 1845, he sold this [large plot of land with a small bungalow] to Khwaja Abdul Ghani. The Khwajas by this time had become one of the leading zamindar families of East Bengal and were eager to demonstrate their status. Within a few years Khwaja Abdul Ghani had built a magnificent country house ... laid out in a beautiful garden. This garden, in the Mughal style, was named Shahbagh, and soon the whole area came to be called by this name.

- ^ Rahman Ali Tayesh, Munshi (1985). Tawarikhe Dhaka (in Bengali). Translated by Sharfuddin, AMM. Dhaka: Islamic Foundation. pp. 158–159. OCLC 59057860.

- ^ "Dhaka under the East India Company". Dhaka City Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ Rahman, Syed Sadiqur (2012). "Ramna Racecourse". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ "Bangladesh Betar". Bangladesh Ministry of Information. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ Hasan, Khalid (12 November 2006). "PostCard USA: Arnold Zeitlin's Pakistan". Daily Times. Archived from the original on 13 June 2006. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ^ Zeitlin, Arnold (16 December 2004). "I would rather die than sign any false statement". The Daily Star. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ^ Badiuzzaman, Syed (21 August 2005). "War and remembrance". Weekly Holiday. Archived from the original on 6 February 2006. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ^ a b Khan, Md. Asadullah (16 December 2004). "My Experience on the First Victory Day". Observer Magazine. The Bangladesh Observer. Archived from the original on 11 February 2006. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ^ Rashid, Harun Ur (17 December 2004). "Gallant Urban Guerrillas of 1971". Star Weekend Magazine. The Daily Star. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ^ "Constituency 181". Constituency List and Map. Bangladesh Election Commission, Government of Bangladesh. 7 March 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ^ All Ward & Commissioners of Mega City Dhaka

- ^ "Thousands join Shahbagh sit-in". The Daily Star. 7 February 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ "Shahbag sit-in demands Mollah's death". Priyo. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013.

- ^ "People burst into protests". New Age. 7 February 2013. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ "Protests rage for third day over Bangladeshi war crimes Islamist". Reuters. 7 February 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ "Shahbag Thana" (Press release) (in Bengali). Dhaka Metropolitan Police. 30 June 2006.

- ^ S.A.T.M. Aminul Hoque. "Water Related Risk Management in Urban Agglomerations in Bangladesh". United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security. Archived from the original on 11 June 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- ^ "Dhaka". Bangla 2000. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- ^ "Fun Facts". University of Dhaka. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2006.

- ^ "Contact Us". Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "Homepage". Dhaka Sheraton. Archived from the original on 22 March 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2006.

- ^ "Homepage". Diabetic Association of Bangladesh. Retrieved 28 September 2006.

- ^ Parveen, Shahnaz (1 July 2003). "Commuting in Dhaka city and its changing phases". Star Lifestyle. The Daily Star. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- ^ "Light Rail Transit in Dhaka". Daily Star Article. Engconsult Ltd. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- ^ Rahman, Sultana (23 June 2004). "DUTP gets more time". The Daily Star. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- ^ "Shahbag's undying appeal: Saving its glory through architectural renovation". The Financial Express. Dhaka. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ "Human sea at Shahbagh". The News Today. 7 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Alamgir, Mohammad (2012). "Shahbag". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Khan, Mubin S (4 November 2005). "Glory days". New Age. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2007.

- ^ Alamgir, Mohammad (2012). "Paribag". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Kamol, Ershad (2 April 2006). "A modern-day theatre tradition second to none". The Daily Star. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ "Hawkewrs on Gausia, Nilkhet footpath". New Age. 21 January 2006. Archived from the original on 26 April 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ "A Favourite Haunt of Book Lovers". The Independent. Dhaka. 30 September 2006. Archived from the original on 24 February 2006. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ Parveen, Shahnaz (12 April 2006). "Shop talk: Beli, Rajanigandha and more". Star Lifestyle. The Daily Star. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ Mehriban, Sharmin (30 November 2005). "Bad days for flower traders at Shahbagh". The Daily Star. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ Khan, Marchel (28 June 2002). "Endangered species being sold". Weekly Holiday. Archived from the original on 23 February 2005. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ Taifoor, Syed Muhammed (1952). Glimpses of Old Dhaka. Dacca: SM Perwez. pp. 257–58. ASIN B0007K0SFK.

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1962) [First published 1956]. Dacca: A Record of its Changing Fortunes (2nd ed.). Dacca: Mrs. Safiya S. Dani. p. 246. OCLC 4715069.

- ^ Aktar, Bayazid (2012). "Art Gallery". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Hossain, Takir (2 July 2020). "Orchid Art Gallery, a promotion hub for Bangladeshi artists". Daily Sun.

- ^ "Homepage". Bangladesh National Museum. Archived from the original on 31 August 2000. Retrieved 28 September 2006.

- ^ Khan, SD (1 November 2005). "The Race Course Maidan that once was". Star Weekend Magazine. The Daily Star. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ^ Duttagupta, Amulyakumar (1938). Shree Shree Ma Anandamayi Prosonge (vol 1) (in Bengali). Dhaka. pp. 2–3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "SGPC to repair Bangladesh gurdwaras". The Tribune India. 25 September 2005. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ "Basanta Utsab observed in city". Weekly Holiday. 7 March 2003. Archived from the original on 14 February 2005. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ "People join in spring festival". New Age. 4 February 2003. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ Parveen, Shahnaz (10 February 2004). "Celebrating the festival of colours". Star Lifestyle. The Daily Star. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ Deepita, Novera (10 April 2006). "Preparation on in full swing". The Daily Star. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ Ahsan, Syed Badrul (14 April 2006). "Speaking of the soul of Bengal..." New Age. Archived from the original on 3 May 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ Shanto, Aminul Haque (14 April 2006). "Celebration of Pahela Baishakh". Bangladesh Independent. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ "Mufti Hannan placed on fresh remand". The Daily Star. 7 October 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ "International Short and Independent Film Festival". Short Film Forum. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2011). "Population & Housing Census" (PDF). Bangladesh Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

References

[edit]- Ahmed, Sharif Uddin (1986). Dacca: A Study in Urban History and Development (1st ed.). London: Curzon Press. ISBN 0-913215-14-7.

- Ahmed, Sharif Uddin (2001). Dhaka: Itihasa o Nagarjiban: 1840–1921.

- Old files and documents preserved at Ahsan Manzil Museum and Nawab State's Office

- Ahsanullah, Nawab, Personal Diary (Urdu) preserved at Ahsan Manzil.

- Geddes, Patrick (1911). Report on Town Planning-Dacca. Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Book Depot.

- Haider, Azimusshan (1966). A City and its Civic Body. Dhaka: Dacca Municipality.

- Haider, Azimusshan (1967). Dacca: History and Romance in Place Names. Dhaka: Dacca Municipality.

- Hardinge of Penshurst, Lord Charles (1948). My Indian Years: 1910–1916. London: John Murray. ASIN B0007IW7V0.

- Hasan, Sayid Aulad (1912). Notes on the Antiquities of Dacca. Dacca: M.M. Bysak. ASIN B0000CQXW3.

- Islam, Nazrul (1996). Dhaka: From city to megacity (Perspectives on people, places, planning, and development issues): Bangladesh urban studies series No. 1. Urban Studies Programme, Department of Geography, University of Dhaka. ISBN 984-510-004-X.

- Mamoon, Muntasir (2004). Dhaka: Smrti Bismrtir Nagari. Dhaka: Ananya Publishers. ISBN 984-412-104-3.

- Maniruzzaman, KM. Dhaka City: A sketch of its development. ASIN B000720FH0.

- Rahman Ali Tayesh, Munshi (1985). Tawarikhe Dhaka (in Bengali). Translated by Sharfuddin, AMM. Dhaka: Islamic Foundation. OCLC 59057860.

- Serajuddin, Asma (1991). Mughal Tombs in Dhaka (ed. by Sharifuddin Ahmed).

- Taifoor, Syed Muhammed (1952). Glimpses of Old Dhaka. Dacca: SM Perwez. ASIN B0007K0SFK.

- Taylor, James (1840). A Sketch of the Topography and Statistics of Dacca. Calcutta: G. H. Huttman, Military Orphan Press.

External links

[edit]- "Map of Thana Shahbagh". Dhaka Metropolitan Police. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007.

- Anandamoyi Ma website