Seveso disaster

The Seveso disaster was an industrial accident that occurred around 12:37 pm on 10 July 1976, in a small chemical manufacturing plant approximately 20 kilometres (12 mi) north of Milan in the Lombardy region of Italy. It resulted in the highest known exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in residential populations,[1] which gave rise to numerous scientific studies and standardized industrial safety regulations, including the European Union's Seveso III Directive. This accident was ranked eighth in a list of the worst man-made environmental disasters by Time magazine in 2010.[2]

Location of disaster

[edit]The Seveso disaster was named after Seveso, the community most affected, which had a population of 17,000 in 1976. Other affected neighbouring communities were Meda (19,000), Desio (33,000), Cesano Maderno (34,000) and to a lesser extent Barlassina (6,000) and Bovisio-Masciago (11,000).[3] The industrial plant, located in Meda, was owned by the company Industrie Chimiche Meda Società Azionaria (Meda Chemical Industries S.A., or ICMESA), a subsidiary of Givaudan, which in turn was a subsidiary of Hoffmann-La Roche (Roche Group). The factory building had been built many years earlier and the local population did not perceive it as a potential source of danger. Moreover, although several exposures of populations to dioxins had occurred before, mostly in industrial accidents, they were of a more limited scale.

Chemical events

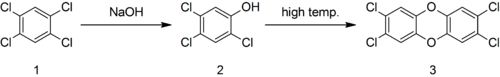

[edit]The accident occurred in the chemical plant's Building B. The chemical 2,4,5-trichlorophenol (2) was being produced there from 1,2,4,5-tetrachlorobenzene (1) by the nucleophilic aromatic substitution reaction with sodium hydroxide. The 2,4,5-trichlorophenol was intended as an intermediate for hexachlorophene.[4]

Reaction temperature was achieved by passing the steam exhaust from the onsite electricity generation turbine through an external heating coil installed on the chemical reactor vessel. The exhaust steam pressure was normally 12 bar and temperature 190 °C, which resulted in a reaction mixture temperature of 158 °C, very close to its boiling point of 160 °C. Safety testing showed the onset of an exothermic (heat-releasing) side reaction if the reaction mixture temperature reached 230 °C. Crucially, no steam temperature reading was made available to plant operators responsible for the reactor.

The chemical-release accident occurred when a batch process was stopped prior to the completion of the final step of removal of ethylene glycol from the reaction mixture by distillation. The process was stopped due to conformance with an Italian law requiring shutdown of plant operations over the weekend. Other parts of the site had already started to close down as the processing of other batches finished, which reduced power consumption across the plant, causing a dramatic drop in the load on the turbine and a consequent increase in the temperature of the exhaust steam to around 300 °C. This hotter than normal steam then heated the portion of the metal wall of the accident reactor above the level of the liquid within it to the same temperature. Not having a steam temperature reading among their instruments, operators of the reactor were unaware of the presence of this additional heating, and they stopped the batch as they normally would by isolating the steam and turning off the stirrer in the reactor vessel. The abnormally hot upper region of the reactor jacket then heated the adjacent reaction mixture. With the stirrer not running, the heating was highly localised to just the portion of the upper layers of reaction mixture adjacent to the reactor wall. The local temperature increased to above the critical temperature for the exothermic side reaction seen in testing. Additionally, the critical temperature proved to be only 180 °C, 50 °C lower than believed. At that lower critical temperature, an exothermic decomposition began, releasing more heat and leading to the onset of a rapid runaway reaction when the temperature reached 230 °C seven hours later.[5][6]

The reactor relief valve eventually opened, causing the aerial release of 6 tonnes of chemicals, which settled over 18 km2 (6.9 sq mi) of the surrounding area.[7] The cloud of substances released contained sodium hydroxide, ethylene glycol, sodium trichlorophenate, and approximately 15 to 30 kg of TCDD (3).[8] At the nominal reaction temperature, TCDD is normally seen only in trace amounts of less than 1 ppm (parts per million).[9][clarification needed] However, in the higher-temperature conditions associated with the runaway reaction, TCDD production apparently reached 166 ppm or more.[10][clarification needed]

Immediate effects

[edit]The affected area was split into zones A, B, and R in decreasing order of surface soil concentrations of TCDD. Zone A was further split into 7 sub-zones. The local population was advised not to touch or eat locally grown fruits or vegetables.

- Zone A had a TCDD soil concentration of > 50 micrograms per square metre (μg/m2); it had between 736[8][11] – 753[12] residents.

- Zone B had a TCDD soil concentration of between 5 and 50 μg/m2; it had 4737 residents.[8]

- Zone R had a negligible concentration of TCDD or up to < 5 μg/m2; it had 31,800 residents.[8]

The population who lived in the path of the aerosol cloud reportedly developed acute symptoms such as headaches, nausea, and eye irritation. 19 children in the area were hospitalized with skin lesions.[12] 500 residents in the area were treated for acute skin irritation. The accident also immediately caused 193 individuals to develop chloracne, none of whom were employed at the ICMESA plant.[12] By the 2nd of August, all residents in Zone A were evacuated and the area was fenced off, however evacuation only began 15 days after the accident took place.[8] After evacuation, all residents of Zone A were medically examined and laboratory tests were performed, Ultimately, 640[13] individuals living in the region were affected with chloracne.

An estimated 25% of all animals in Zone A died immediately after exposure to the aerosol cloud,[11] and by the end July, 3,300 animals, mostly poultry and rabbits, were found dead.[12] Emergency slaughtering commenced to prevent TCDD from entering the food chain, and by 1978 over 80,000 animals had been culled.[12]

The residents of Zone B were not evacuated but were given warnings to refrain from eating locally-grown produce and poultry. The residents of Zone B were given medical examinations and clinical laboratory tests. Pregnant women and children under 12 years old were relocated on a daily basis.[8]

Residents of Zone R were only warned to not eat locally grown foods.[8]

An advice center was set up for pregnant women, of whom 26[citation needed] opted for an abortion (which was legal in special cases) after consultation. Another 460 women continued their pregnancies without problems, their children not showing any sign of malformation.[citation needed] Herwig von Zwehl (Technical Director of ICMESA) and Paolo Paoletti (director of production at ICMESA) were arrested. Two government commissions were established to develop a plan for quarantining and decontaminating the area, for which the Italian government allotted 40 billion lire (US$47.8 million). This amount was tripled two years later.

Studies on immediate and long-term health effects

[edit]A 1991 study,[14] fourteen years after the accident, sought to assess the effects to the thousands of persons that had been exposed to dioxin. The most evident adverse health effect ascertained was chloracne (193 cases). Other early effects noted were peripheral neuropathy and liver enzyme induction. The ascertainment of other, possibly severe sequelae of dioxin exposure (e.g., birth defects) was hampered by inadequate information; however, generally, no increased risks were evident.

A study published in 1998 concluded that chloracne (nearly 200 cases with a definite exposure dependence) was the only effect established with certainty. Early health investigations including liver function, immune function, neurologic impairment, and reproductive effects yielded inconclusive results.

An excess mortality rate from cardiovascular and respiratory diseases was uncovered, and excess of diabetes cases was also found. Results of cancer incidence and mortality follow-up showed an increased occurrence of cancer of the gastrointestinal sites and of the lymphatic and hematopoietic tissue. Results cannot be viewed as final or comprehensive, however, because of various limitations: the lack of individual exposure data, short latency period, and small population size for certain cancer types.

A 2001 study confirmed in victims of the disaster, that dioxin is carcinogenic to humans and corroborate its association with cardiovascular- and endocrine-related effects. In 2009, an update including 5 more years (up to 1996) found an increase in "lymphatic and hematopoietic tissue neoplasms" and increased breast cancer.[15]

A 2008 study[16] evaluated whether maternal exposure is associated with modified neonatal thyroid function in the highly exposed population in Seveso and concluded that environmental contaminants such as dioxins have a long-lasting capability to modify neonatal thyroid function after the initial exposure.

The male children of mothers who were, during pregnancy of those children, exposed to high levels of toxic dioxins due to the Seveso disaster, have been found to have lower-than-average sperm counts. This result of the underlying Seveso study has been noted to provide the most pronounced evidence for prenatal exposure to an environmental chemical causing low sperm counts.[17]

Cleanup operations

[edit]In January 1977, an action plan consisting of scientific analysis, economic aid, medical monitoring and restoration/decontamination was completed. Shortly after ICMESA began to pay the first compensations to those affected. Later that spring decontamination operations were initiated and in June a system epidemiological health monitoring for 220,000 people was launched. They then used trichlorophenol to make a drug to fight the skin infections, which they tested in dogs.

In June 1978, the Italian government raised its special loan from 40 to 115 billion lire. By the end of the year, most individual compensation claims had been settled out of court. On 5 February 1980, Paolo Paoletti (the Director of Production at ICMESA) was shot and killed in Monza by a member of the Italian radical left-wing terrorist organization Prima Linea.[18]

On 19 December 1980, representatives of the Region of Lombardy/Italian Republic and Givaudan/ICMESA signed a compensation agreement in the presence of the prime minister of Italy, Arnaldo Forlani. The total amount would reach 20 billion lire.

Waste from the cleanup

[edit]The waste from the clean up of the plant was a mixture of protective clothing and chemical residues from the plant. This waste was packed into waste drums which had been designed for the storage of nuclear waste. It was agreed that the waste would be disposed of in a legal manner.

To this end, in spring 1982, the firm Mannesmann Italiana was contracted to dispose of the contaminated chemicals from Zone A. Mannesmann Italiana made it a condition that Givaudan would not be notified of the disposal site which prompted Givaudan to insist that a notary public certify the disposal. On 9 September, 41 barrels of toxic waste left the ICMESA premises. On 13 December, the notary gave a sworn statement that the barrels had been disposed of in an approved way.

However, in February 1983, the programme A bon entendeur on Télévision Suisse Romande, a French language Swiss television channel, followed the route of the barrels to Saint-Quentin in northern France where they disappeared. A public debate ensued in which numerous theories were put forward when it was found that Mannesmann Italiana had hired two subcontractors to dispose of the toxic waste. On 19 May, the 41 barrels were found in an unused abattoir in Anguilcourt-le-Sart, a village in northern France. From there they were transferred to a French military base near Sissonne. The Roche Group (parent firm of Givaudan) took it upon itself to properly dispose of the waste. On 25 November, over nine years after the disaster, the Roche Group issued a public statement that the toxic waste consisting of 42 barrels (one was added earlier that year) had all been incinerated in Switzerland. According to New Scientist, it was thought that the high chlorine content of the waste might cause damage to the high temperature incinerator used by Roche, but Roche stated that they would burn the waste in the incinerator and repair it afterward if it were damaged. They stated that they wanted to take responsibility for the safe destruction of the waste.

Criminal court case

[edit]This section needs expansion with: Explaining what this criminal court case was about: the cleanup operations (it's in a sub-section) or the general disaster?. You can help by adding to it. (September 2022) |

In September 1983, the Criminal Court of Monza sentenced five former employees of ICMESA or its parent company, Givaudan, to prison sentences ranging from 2.5 years to 5 years. They all appealed.

In May 1985, the Court of Appeal in Milan found three of the five accused not guilty; the two still facing prosecution appealed to the Supreme Court in Rome.

On 23 May 1986, the Supreme Court in Rome confirmed the judgment against the two remaining defendants, even though the prosecuting attorney had called for their acquittal.

Aftermath

[edit]After the incident, ICMESA initially refused to admit that the dioxin release had occurred. At least a week passed before a public statement was issued that dioxin had been emitted, and another week passed before an evacuation began. Even then, the government was saddled with the responsibility of determining the boundaries of the evacuation area, and thereafter to organise the evacuation. This constituted a major imposition on the community as well as on government resources.

It was soon recognized that the factory's very rudimentary safety systems had been designed with little more than simple explosion prevention in mind. Environmental protection had not been considered. Nor had any consideration been given as to setting up any type of warning system or health-protection protocols for the local community. As a result, the local population was caught unaware when the accident happened, and thus was unprepared to cope with the danger of an invisible poison.

In the context of such heightened tensions, Seveso became a microcosm where all the existing conflicts within society (political, institutional, religious, industrial) were reflected. However, within a relatively short time, such conflicts abated and the recovery of the community proceeded. For, in Seveso, the responsible party was known from the outset and soon offered reparation. Moreover, the eventual disappearance of the offending factory itself and the physical exportation of the toxic substances and polluted soil enabled the community to feel cleansed. The resolution of the emotional after-effects of the trauma, so necessary for the recovery of a community, was facilitated by these favourable circumstances."[19]

Industrial safety regulations were passed in the European Community in 1982 called the Seveso Directive,[20] which imposed much stronger industrial regulations. The Seveso Directive was updated in 1996, 2008 and 2012 and is currently referred to as the Seveso III Directive (or COMAH Regulations in the United Kingdom).

Treatment of the soil in the affected areas is now considered complete, since the dioxin levels are now below background. The entire site has been turned into a public park known as Seveso Oak Forest Park. This area is permanently off-limits to development. There are two artificial hills in the park; today, underneath these hills are the toxic remnants (including destroyed houses, tons of contaminated soil, and animal remains), all protected in a concrete sarcophagus. Investigations into site conditions have confirmed that the sarcophagus life expectancy of 300 years is expected, appropriate, and required.[citation needed]

Several studies have been completed on the health of the population of surrounding communities. While it has been established that people from Seveso exposed to TCDD are more susceptible to certain rare cancers, when all types of cancers are grouped into one category, no statistically significant increase has yet been reported in any specific cancer category. This indicates that more research is needed to determine the true long-term health effects on the affected population.

Epidemiological monitoring programmes were established as follows (with termination dates): abortions (1982); malformations (1982); tumours (1997); deaths (1997). Health monitoring of workers at ICMESA and on decontamination projects, and chloracne sufferers (1985)[21]

The documentary Gambit[22][23] is about Jörg Sambeth, the technical director of ICMESA, who was sentenced to five years in the first trial, and had his sentence reduced to two years and was paroled on appeal.[24]

See also

[edit]- Environmental inequality in Europe

- Inochi No Chikyuu: Dioxin No Natsu (a 2001 film about the incident)

- "Suffocation," the fifth track on the dystopian concept album, See You Later, by Vangelis, is inspired by the Seveso disaster and features an emergency announcement in Italian to take shelter and a dialog between a man and woman set during the unfolding of the disaster.[25]

- "Seveso Directive", one of three European Union Directives to improve the safety of sites containing large quantities of dangerous substances:

- Directive 82/501/EC, also known as the "Seveso Directive"

- Directive 96/82/EC, also known as the "Seveso II Directive"

- Directive 2012/18/EU, also known as the "Seveso III Directive"

References

[edit]- ^ Eskenazi, Brenda; Mocarelli, Paolo; Warner, Marcella; Needham, Larry; Patterson, Donald G. Jr.; Samuels, Steven; Turner, Wayman; Gerthoux, Pier Mario; Brambilla, Paolo (January 2004). "Relationship of Serum TCDD Concentrations and Age at Exposure of Female Residents of Seveso, Italy". Environmental Health Perspectives. 112 (1): 22–7. doi:10.1289/ehp.6573. PMC 1241792. PMID 14698926.

- ^ "Top 10 Environmental Disasters".

- ^ B. De Marchi; S. Funtowicz; J. Ravetz. "4 Seveso: A paradoxical classic disaster". United Nations University.

- ^ Homberger, E.; Reggiani, G.; Sambeth, J.; Wipf, H. K. (1979). "The Seveso Accident: Its Nature, Extent and Consequences". Ann. Occup. Hyg. 22 (4). Pergamon Press: 327–370. doi:10.1093/annhyg/22.4.327. PMID 161954.

- ^ Kletz, Trevor (1998). What Went Wrong? Case Histories of Process Plant Disasters. Gulf. ISBN 0-88415-920-5.

- ^ Kletz, Trevor A. (2001). "Ch. 9)". Learning from Accidents (3rd ed.). Oxford U.K.: Gulf Professional. pp. 103–109. ISBN 978-0-7506-4883-7.

- ^ "Seveso – 30 Years After, A Chronology of Events". Roche Group.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eskenazi, Brenda; Warner, Marcella; Brambilla, Paolo; Signorini, Stefano; Ames, Jennifer; Mocarelli, Paolo (2018-12-01). "The Seveso accident: A look at 40 years of health research and beyond". Environment International. 121 (Pt 1): 71–84. Bibcode:2018EnInt.121...71E. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.051. ISSN 0160-4120. PMC 6221983. PMID 30179766.

- ^ Milnes, M. H. (6 August 1971). "Formation of 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzodioxin by Thermal Decomposition of Sodium 2,4,5-Trichlorophenate". Nature. 232 (5310). Nature Publishing Group: 395–396. Bibcode:1971Natur.232..395M. doi:10.1038/232395a0. PMID 16063057. S2CID 4215351.

- ^ Hay, Alastair (18 October 1979). "Séveso: the crucial question of reactor safety". Nature. 281 (5732). Nature Publishing Group: 521. Bibcode:1979Natur.281..521H. doi:10.1038/281521a0. S2CID 38191411.

- ^ a b Eskenazi, Brenda; Mocarelli, Paolo; Warner, Marcella; Samuels, Steven; Vercellini, Paolo; Olive, David; Needham, Larry; Patterson, Donald; Brambilla, Paolo (2000-05-01). "Seveso Women's Health Study: a study of the effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on reproductive health". Chemosphere. 40 (9): 1247–1253. Bibcode:2000Chmsp..40.1247E. doi:10.1016/S0045-6535(99)00376-8. ISSN 0045-6535. PMID 10739069.

- ^ a b c d e Assennato, G; Cervino, D; Emmett, EA; Longo, G; Merlo, F (January 1, 1989). "Follow-up of subjects who developed chloracne following TCDD exposure at Seveso". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 16 (2): 119–125. doi:10.1002/ajim.4700160203. PMID 2773943 – via Wiley.

- ^ Roche Group (January 1997). "Seveso 20 years after" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 17, 2023. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ Bertazzi, Pier Alberto (1991). "Long-term effects of chemical disasters. Lessons and results from Seveso". The Science of the Total Environment. 106 (1–2): 5–20. Bibcode:1991ScTEn.106....5B. doi:10.1016/0048-9697(91)90016-8. PMID 1835132.

- ^ Pesatori, A.; Consonni, D.; Rubagotti, M.; Grillo, P.; Bertazzi, P. (2009). "Cancer incidence in the population exposed to dioxin after the "Seveso accident": twenty years of follow-up". Environmental Health. 8 (1): 39. Bibcode:2009EnvHe...8...39P. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-8-39. PMC 2754980. PMID 19754930.Free full-text

- ^ Baccarelli, Andrea; Giacomini, Sara M.; Corbetta, Carlo; Landi, Maria Teresa; Bonzini, Matteo; Consonni, Dario; Grillo, Paolo; Jr, Donald G. Patterson; Pesatori, Angela C.; Bertazzi, Pier Alberto (2008-07-29). "Neonatal Thyroid Function in Seveso 25 Years after Maternal Exposure to Dioxin". PLOS Medicine. 5 (7): e161. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050161. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 2488197. PMID 18666825.

- ^ "Out for the count: Why levels of sperm in men are falling". The Independent. 25 April 2010.

- ^ Robbe, F (2016). "Seveso 1976. Oltre la diossina". Itaca. pp. 119–120.

- ^ B. De Marchi; S. Funtowicz; J. Ravetz. "Conclusion: "Seveso" – A paradoxical symbol". United Nations University.

- ^ "Original Seveso Directive 82/501/EEC ("Seveso I")" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-10.

- ^ "Vietnam Agent Orange Campaign – Background". Archived from the original on 2006-08-21.

- ^ Gambit (2005), German Wikipedia page. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gambit_(2005), accessed (in German) on December 28, 2019.

- ^ Gambit (August 2005), Sabine Gisiger, Swiss Films Review. https://www.swissfilms.ch/en/film_search/filmdetails/-/id_film/-1704568495

- ^ "Ich war absolut dumm". Die Tageszeitung: Taz (in German). 2006-07-10. p. 4.

- ^ "Original Italian lyrics with English translation". Song Meanings. June 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Fuller, John G. (1979). Poison That Fell from the Sky. New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 0-425-04013-5.

- Robbe, Federico (2016). Seveso 1976. Oltre la diossina. Castel Bolognese: Itaca Books. ISBN 978-88-526-0486-7.

External links

[edit]- Loss Prevention Bulletin The Seveso Disaster: An appraisal of its causes and circumstances,[permanent dead link] Marshallvagri, V.C., LPB Issue 104, April 1992, IChemE, UK.

- National Pollutant Inventory – Dioxin Fact Sheet

- Dioxin: Seveso disaster testament to effects of dioxin, article by Mick Corliss, May 6, 1999.

- Icmesa chemical company, Seveso, Italy. July 9, 1976 British Health & Safety Executive COMAH information page on the Seveso Disaster.

- Assessment of the Health Risks of Dioxins, a 1998 report by the World Health Organization.

- Roche – 1965–1978 pdf History timeline at the homepage of Hoffmann-LaRoche.

- Dunning, Brian (January 30, 2024). "Skeptoid #921: Reconsidering the Seveso Dioxin Disaster". Skeptoid.