Mopsuestia

Μοψουεστία | |

Roman bridge in Misis-Mopsuestia over the Pyramus | |

| Alternative name | Mopsos, Seleucia on the Pyramus, Hadriana, Decia, al-Maṣṣīṣah, Mamistra, Misis, Yakapınar |

|---|---|

| Location | Adana Province, Turkey |

| Region | Cilicia |

| Coordinates | 36°57′28″N 35°37′26″E / 36.95778°N 35.62389°E |

| Type | Settlement |

Mopsuestia (Ancient Greek: Μοψουεστία and Μόψου ἑστία, romanized: Mopsou(h)estia and Μόψου Mopsou and Μόψου πόλις and Μόψος; Byzantine Greek: Mamista, Manistra, Mampsista; Arabic: al-Maṣṣīṣah; Armenian: Msis, Mises, Mam(u)estia; modern Yakapınar) is an ancient city in Cilicia Campestris on the Pyramus River (now the Ceyhan River) located approximately 20 km (12 mi) east of ancient Antiochia in Cilicia (present-day Adana, southern Turkey). From the city's harbor, the river is navigable to the Mediterranean Sea, a distance of over 40 km (24 mi).

The 1879 book A Latin Dictionary, the 1898 book Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia and the 1920 La Cilicie mention that the city at that time was called Missis or Messis,[1][2][3][4] but in 1960 the name changed to Yakapınar.[5]

History

[edit]The founding of this city is attributed to the seer Mopsus,[6][7] from whom the city also took its name,[8] who lived before the Trojan War, although it is scarcely mentioned before the Christian era. The name has been glossed as Μόψου ἑστία, "The house (hestia) of Mopsus". Pliny the Elder calls it the free city of Mopsos (Hist. nat., V, 22), but the ordinary name is Mopsuestia, as found in Stephanus of Byzantium and all the Christian geographers and chroniclers. Under the Seleucid Empire, the city took the name of Seleucia on the Pyramus (classical Greek: Σελεύκεια πρὸς τὸν Πύραμον, Seleukeia pros ton Pyramon; Latin: Seleucia ad Pyramum), but gave it up at the time of the Roman conquest. Coins and inscriptions show that under Hadrian it was called Hadriana, under Decius Decia, and so forth. Constantius II built there a magnificent bridge over the Pyramus (Malalas, Chronographia, XIII; P.G., XCVII, 488) afterwards restored by Justinian (Procopius, De Edificiis, V. 5) and has been restored again recently.

Near the city a battle between the Antiochus X Eusebes, son of Antiochus IX Cyzicenus, and Seleucus VI Epiphanes was fought. Antiochus won and Seleucus took shelter in Mopsuestia, but the citizens of Mopsuestia killed him. His brothers Antiochus XI and Philip I destroyed Mopsuestia as an act of revenge and their armies fought those of Antiochus X, but they lost.[9]

Christianity seems to have been introduced very early into Mopsuestia, and during the 3rd century, there is mention of a bishop, Theodorus, the adversary of Paul of Samosata. Other famous residents of the early Christian period in the city's history include Saint Auxentius (d. 360), and Theodore, bishop from 392–428, the teacher of Nestorius. The bishopric is included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees.[10] Along with much of Cilicia, the region was wrested from Roman control by the Arabs in the late 630s.

In 684 the Emperor Constantine IV recaptured Misis from its small Arab garrison and it remained an imperial possession until 703 (Theophanes, "Chronogr.", A. M. 6178, 6193), when it was recaptured by the Arabs, who rebuilt the fortifications, constructed a mosque, and maintained a permanent garrison.[11] Because of its position on the frontier, the city was repeatedly fought over and was recaptured from time to time by the Byzantines: it was besieged in vain by the Byzantine troops of John I Tzimisces in 964, but was taken the following year after a long and difficult siege by Nicephorus Phocas.[12]

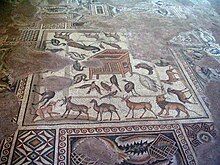

Mopsuestia then numbered 200,000 inhabitants, some of whom were Muslim, and the Byzantines made efforts to re-Christianize the city. In the early 1090s, Turkish forces overran the town, but were expelled in 1097 by Crusader troops under Tancred who took possession of the city and its strategic port, which were annexed to the Principality of Antioch. It suffered much from the internecine war between Crusaders, Armenians, and Greeks who lost it and recaptured it, notably in 1106, 1132, and 1137. Finally, in 1151–1152 the Armenian Baron T'oros II captured the city and defeated the Greek counterattack led by Andronikos I Komnenos. Thereafter it remained a possession of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, but was briefly captured and plundered by the Mamluks in 1266, 1275, and 1322. The Venetians and Genoese were licensed by the Armenians to maintain warehouses near the harbor to store goods brought from India. The Armenians were permanently evicted by the Mamluks in 1347.[11] The city was the site of several church councils and possessed four Armenian churches; the Greek diocese still existed at the beginning of the fourteenth century (Le Quien, Oriens Christianus, II, 1002). In 1432 the Frenchman Bertrandon reported that the city was ruled by the Muslims and was largely destroyed. In 1515 Mopsuestia, and the whole of Cilicia was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire by Sultan Selim I. Since then it has steadily declined and became the small village of Misis. Misis was renamed Yakapınar in the 1960s. Only fragments of the medieval fortifications survive today. However, an etching of the circuit walls and towers was made in the mid-19th century.[13] The Misis Mosaic Museum was founded in 1959 to exhibit the mosaics found in the area, including the famous "Samson Mosaic".

Victor Langlois wrote that he found a beautiful Greek inscription at the city and while he was trying to move it to France, the inscription fell in the Pyramus River.[14]

Notable people

[edit]- Heracleides (Ancient Greek: Ἡρακλείδης) was a grammarian from Mopsus.[8][15]

- Theodore of Mopsuestia, bishop of Mopsuestia

- Auxentius of Mopsuestia, bishop of Mopsuestia

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Mopsuestia

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, Mopsuestia

- ^ Vailhé, Siméon (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10.

- ^ Normand Robert, La Cilicia. In: Annals of Geography. 1920, vol. 29, No. 162. p.p. 426-451

- ^ Missis and its Roman bridge

- ^ GREEK ANTHOLOGY, § 9.698

- ^ Procopius, On Buildings, §5.5.1

- ^ a b Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, § M459.1

- ^ Eusebius, Chronography, 97-98

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 933

- ^ a b Edwards, Robert W. (1987). The Fortifications of Armenian Cilicia: Dumbarton Oaks Studies XXIII. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. pp. 198–200, 284. ISBN 0-88402-163-7.

- ^ Edwards, Robert W., "Mopsuestia" (2016). The Eerdmans Encyclopedia of Early Christian Art and Archaeology, ed., Paul Corby Finney. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-8028-9017-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Langlois, V. (1861). Voyage dans la Cilicie et dans les montagnes du Taurus, exécuté pendant les années 1852-1853. Paris. p. 451.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Missis and its Roman bridge

- ^ Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, §6.234b

Sources

[edit]- Hild, Friedrich; Hellenkemper, Hansgerd (1990). Tabula Imperii Byzantini, Band 5: Kilikien und Isaurien (in German). Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 3-7001-1811-2.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Vailhé, Siméon (1911). "Mopsuestia". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Vailhé, Siméon (1911). "Mopsuestia". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10.