Seismic wave

| Part of a series on |

| Earthquakes |

|---|

|

A seismic wave is a mechanical wave of acoustic energy that travels through the Earth or another planetary body. It can result from an earthquake (or generally, a quake), volcanic eruption, magma movement, a large landslide and a large man-made explosion that produces low-frequency acoustic energy. Seismic waves are studied by seismologists, who record the waves using seismometers, hydrophones (in water), or accelerometers. Seismic waves are distinguished from seismic noise (ambient vibration), which is persistent low-amplitude vibration arising from a variety of natural and anthropogenic sources.

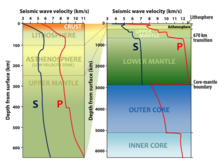

The propagation velocity of a seismic wave depends on density and elasticity of the medium as well as the type of wave. Velocity tends to increase with depth through Earth's crust and mantle, but drops sharply going from the mantle to Earth's outer core.[2]

Earthquakes create distinct types of waves with different velocities. When recorded by a seismic observatory, their different travel times help scientists locate the quake's hypocenter. In geophysics, the refraction or reflection of seismic waves is used for research into Earth's internal structure. Scientists sometimes generate and measure vibrations to investigate shallow, subsurface structure.

Types

[edit]Among the many types of seismic waves, one can make a broad distinction between body waves, which travel through the Earth, and surface waves, which travel at the Earth's surface.[3]: 48–50 [4]: 56–57

Other modes of wave propagation exist than those described in this article; though of comparatively minor importance for earth-borne waves, they are important in the case of asteroseismology.

- Body waves travel through the interior of the Earth.

- Surface waves travel across the surface. Surface waves decay more slowly with distance than body waves which travel in three dimensions.

- Particle motion of surface waves is larger than that of body waves, so surface waves tend to cause more damage.

Body waves

[edit]Body waves travel through the interior of the Earth along paths controlled by the material properties in terms of density and modulus (stiffness). The density and modulus, in turn, vary according to temperature, composition, and material phase. This effect resembles the refraction of light waves. Two types of particle motion result in two types of body waves: Primary and Secondary waves. This distinction was recognized in 1830 by the French mathematician Siméon Denis Poisson.[5]

Primary waves

[edit]Primary waves (P waves) are compressional waves that are longitudinal in nature. P waves are pressure waves that travel faster than other waves through the earth to arrive at seismograph stations first, hence the name "Primary". These waves can travel through any type of material, including fluids, and can travel nearly 1.7 times faster than the S waves. In air, they take the form of sound waves, hence they travel at the speed of sound. Typical speeds are 330 m/s in air, 1450 m/s in water and about 5000 m/s in granite.

Secondary waves

[edit]Secondary waves (S waves) are shear waves that are transverse in nature. Following an earthquake event, S waves arrive at seismograph stations after the faster-moving P waves and displace the ground perpendicular to the direction of propagation. Depending on the propagational direction, the wave can take on different surface characteristics; for example, in the case of horizontally polarized S waves, the ground moves alternately to one side and then the other. S waves can travel only through solids, as fluids (liquids and gases) do not support shear stresses. S waves are slower than P waves, and speeds are typically around 60% of that of P waves in any given material. Shear waves can not travel through any liquid medium,[6] so the absence of S waves in earth's outer core suggests a liquid state.

Surface waves

[edit]Seismic surface waves travel along the Earth's surface. They can be classified as a form of mechanical surface wave. Surface waves diminish in amplitude as they get farther from the surface and propagate more slowly than seismic body waves (P and S). Surface waves from very large earthquakes can have globally observable amplitude of several centimeters.[7]

Rayleigh waves

[edit]Rayleigh waves, also called ground roll, are surface waves that propagate with motions that are similar to those of waves on the surface of water (note, however, that the associated seismic particle motion at shallow depths is typically retrograde, and that the restoring force in Rayleigh and in other seismic waves is elastic, not gravitational as for water waves). The existence of these waves was predicted by John William Strutt, Lord Rayleigh, in 1885.[8] They are slower than body waves, e.g., at roughly 90% of the velocity of S waves for typical homogeneous elastic media. In a layered medium (e.g., the crust and upper mantle) the velocity of the Rayleigh waves depends on their frequency and wavelength. See also Lamb waves.

Love waves

[edit]Love waves are horizontally polarized shear waves (SH waves), existing only in the presence of a layered medium.[9] They are named after Augustus Edward Hough Love, a British mathematician who created a mathematical model of the waves in 1911.[10] They usually travel slightly faster than Rayleigh waves, about 90% of the S wave velocity.

Stoneley waves

[edit]A Stoneley wave is a type of boundary wave (or interface wave) that propagates along a solid-fluid boundary or, under specific conditions, also along a solid-solid boundary. Amplitudes of Stoneley waves have their maximum values at the boundary between the two contacting media and decay exponentially away from the contact. These waves can also be generated along the walls of a fluid-filled borehole, being an important source of coherent noise in vertical seismic profiles (VSP) and making up the low frequency component of the source in sonic logging.[11] The equation for Stoneley waves was first given by Dr. Robert Stoneley (1894–1976), emeritus professor of seismology, Cambridge.[12][13]

Normal modes

[edit]

Free oscillations of the Earth are standing waves, the result of interference between two surface waves traveling in opposite directions. Interference of Rayleigh waves results in spheroidal oscillation S while interference of Love waves gives toroidal oscillation T. The modes of oscillations are specified by three numbers, e.g., nSlm, where l is the angular order number (or spherical harmonic degree, see Spherical harmonics for more details). The number m is the azimuthal order number. It may take on 2l+1 values from −l to +l. The number n is the radial order number. It means the wave with n zero crossings in radius. For spherically symmetric Earth the period for given n and l does not depend on m.

Some examples of spheroidal oscillations are the "breathing" mode 0S0, which involves an expansion and contraction of the whole Earth, and has a period of about 20 minutes; and the "rugby" mode 0S2, which involves expansions along two alternating directions, and has a period of about 54 minutes. The mode 0S1 does not exist because it would require a change in the center of gravity, which would require an external force.[3]

Of the fundamental toroidal modes, 0T1 represents changes in Earth's rotation rate; although this occurs, it is much too slow to be useful in seismology. The mode 0T2 describes a twisting of the northern and southern hemispheres relative to each other; it has a period of about 44 minutes.[3]

The first observations of free oscillations of the Earth were done during the great 1960 earthquake in Chile. Presently the periods of thousands of modes have been observed. These data are used for constraining large scale structures of the Earth's interior.

P and S waves in Earth's mantle and core

[edit]When an earthquake occurs, seismographs near the epicenter are able to record both P and S waves, but those at a greater distance no longer detect the high frequencies of the first S wave. Since shear waves cannot pass through liquids, this phenomenon was original evidence for the now well-established observation that the Earth has a liquid outer core, as demonstrated by Richard Dixon Oldham. This kind of observation has also been used to argue, by seismic testing, that the Moon has a solid core, although recent geodetic studies suggest the core is still molten[citation needed].

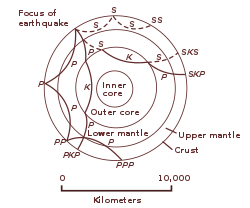

Notation

[edit]

The naming of seismic waves is usually based on the wave type and its path; due to the theoretically infinite possibilities of travel paths and the different areas of application, a wide variety of nomenclatures have emerged historically, the standardization of which – for example in the IASPEI Standard Seismic Phase List – is still an ongoing process.[14] The path that a wave takes between the focus and the observation point is often drawn as a ray diagram. Each path is denoted by a set of letters that describe the trajectory and phase through the Earth. In general, an upper case denotes a transmitted wave and a lower case denotes a reflected wave. The two exceptions to this seem to be "g" and "n".[14][15]

| c | the wave reflects off the outer core |

| d | a wave that has been reflected off a discontinuity at depth d |

| g | a wave that only travels through the crust |

| i | a wave that reflects off the inner core |

| I | a P wave in the inner core |

| h | a reflection off a discontinuity in the inner core |

| J | an S wave in the inner core |

| K | a P wave in the outer core |

| L | a Love wave sometimes called LT-Wave (Both caps, while an Lt is different) |

| n | a wave that travels along the boundary between the crust and mantle |

| P | a P wave in the mantle |

| p | a P wave ascending to the surface from the focus |

| R | a Rayleigh wave |

| S | an S wave in the mantle |

| s | an S wave ascending to the surface from the focus |

| w | the wave reflects off the bottom of the ocean |

| No letter is used when the wave reflects off of the surfaces |

For example:

- ScP is a wave that begins traveling towards the center of the Earth as an S wave. Upon reaching the outer core the wave reflects as a P wave.

- sPKIKP is a wave path that begins traveling towards the surface as an S wave. At the surface, it reflects as a P wave. The P wave then travels through the outer core, the inner core, the outer core, and the mantle.

Usefulness of P and S waves in locating an event

[edit]

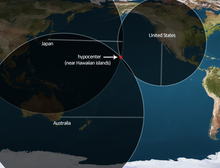

In the case of local or nearby earthquakes, the difference in the arrival times of the P and S waves can be used to determine the distance to the event. In the case of earthquakes that have occurred at global distances, three or more geographically diverse observing stations (using a common clock) recording P wave arrivals permits the computation of a unique time and location on the planet for the event. Typically, dozens or even hundreds of P wave arrivals are used to calculate hypocenters. The misfit generated by a hypocenter calculation is known as "the residual". Residuals of 0.5 second or less are typical for distant events, residuals of 0.1–0.2 s typical for local events, meaning most reported P arrivals fit the computed hypocenter that well. Typically a location program will start by assuming the event occurred at a depth of about 33 km; then it minimizes the residual by adjusting depth. Most events occur at depths shallower than about 40 km, but some occur as deep as 700 km.

A quick way to determine the distance from a location to the origin of a seismic wave less than 200 km away is to take the difference in arrival time of the P wave and the S wave in seconds and multiply by 8 kilometers per second. Modern seismic arrays use more complicated earthquake location techniques.

At teleseismic distances, the first arriving P waves have necessarily travelled deep into the mantle, and perhaps have even refracted into the outer core of the planet, before travelling back up to the Earth's surface where the seismographic stations are located. The waves travel more quickly than if they had traveled in a straight line from the earthquake. This is due to the appreciably increased velocities within the planet, and is termed Huygens' Principle. Density in the planet increases with depth, which would slow the waves, but the modulus of the rock increases much more, so deeper means faster. Therefore, a longer route can take a shorter time.

The travel time must be calculated very accurately in order to compute a precise hypocenter. Since P waves move at many kilometers per second, being off on travel-time calculation by even a half second can mean an error of many kilometers in terms of distance. In practice, P arrivals from many stations are used and the errors cancel out, so the computed epicenter is likely to be quite accurate, on the order of 10–50 km or so around the world. Dense arrays of nearby sensors such as those that exist in California can provide accuracy of roughly a kilometer, and much greater accuracy is possible when timing is measured directly by cross-correlation of seismogram waveforms.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ G. R. Helffrich & B. J. Wood (2002). "The Earth's mantle" (PDF). Nature. 412 (2 August). Macmillan Magazines: 501–7. doi:10.1038/35087500. PMID 11484043. S2CID 4304379. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2016.

- ^ Shearer 2009, Introduction

- ^ a b c Shearer 2009, Chapter 8 (Also see errata Archived 2013-11-11 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Seth Stein; Michael Wysession (1 April 2009). An Introduction to Seismology, Earthquakes, and Earth Structure. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-14443-1131-0.

- ^ Poisson, S. D. (1831). "Mémoire sur la propagation du mouvement dans les milieux élastiques" [Memoir on the propagation of motion in elastic media]. Mémoires de l'Académie des Sciences de l'Institut de France (in French). 10: 549–605.

- ^ "Seismic Waves". Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ Sammis, C.G.; Henyey, T.L. (1987). Geophysics Field Measurements. Academic Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-08-086012-1.

- ^ Rayleigh, Lord (1885). "On waves propagated along the plane surface of an elastic solid". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society. 17: 4–11.

- ^ Sheriff, R. E.; Geldart, L. P. (1995). Exploration Seismology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-521-46826-4.

- ^ Love, A.E.H. (1911). Some problems of geodynamics; …. London, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 144–178.

- ^ "Schlumberger Oilfield Glossary. Stoneley wave". Archived from the original on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ^ Stoneley, R. (October 1, 1924). "Elastic waves at the surface of separation of two solids". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A. 106 (738): 416–428. Bibcode:1924RSPSA.106..416S. doi:10.1098/rspa.1924.0079.

- ^ Robert Stoneley, 1929 – 2008.. Obituary of his son with reference to discovery of Stoneley waves.

- ^ a b Storchak, D. A.; Schweitzer, J.; Bormann, P. (2003-11-01). "The IASPEI Standard Seismic Phase List". Seismological Research Letters. 74 (6): 761–772. doi:10.1785/gssrl.74.6.761. ISSN 0895-0695.

- ^ The notation is taken from Bullen, K.E.; Bolt, Bruce A. (1985). An introduction to the theory of seismology (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521283892. and Lee, William H.K.; Jennings, Paul; Kisslinger, Carl; et al., eds. (2002). International handbook of earthquake and engineering seismology. Amsterdam: Academic Press. ISBN 9780080489223.

Sources

[edit]- Shearer, Peter M. (2009). Introduction to Seismology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88210-1.