Scofield Reference Bible

| Scofield Reference Bible | |

|---|---|

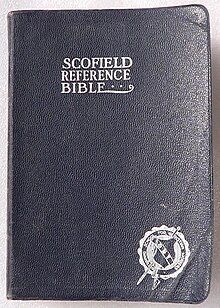

Cover of a 1917 edition of the Scofield Bible presented as a gift in 1941. | |

| Other names | KJV Scofield Study Bible |

| Language | English |

| Complete Bible published | 1909 |

| Online as | Scofield Reference Bible at Wikisource |

| Authorship | Cyrus I. Scofield (editor) |

| Derived from | King James Version |

| Revision | 1917 |

| Publisher | Oxford University Press |

| Religious affiliation | Dispensationalism |

| Website | scofieldbible |

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life. | |

The Scofield Reference Bible is a widely circulated study Bible. Edited and annotated by the American Bible student Cyrus I. Scofield, it popularized dispensationalism at the beginning of the 20th century. Published by Oxford University Press and containing the entire text of the traditional, Protestant King James Version, it first appeared in 1909 and was revised by the author in 1917.[1]

Features and legacy

[edit]

The Scofield Bible had several innovative features. Most important, it printed what amounted to a commentary on the biblical text alongside the Bible instead of in a separate volume, the first to do so in English since the Geneva Bible (1560).[2] It also contained a cross-referencing system that tied together related verses of Scripture and allowed a reader to follow biblical themes from one chapter and book to another (so called "chain references"). Finally, the 1917 edition also attempted to date events of the Bible. It was in the pages of the Scofield Reference Bible that many Christians first encountered Archbishop James Ussher's calculation of the date of Creation as 4004 BC; and through discussion of Scofield's notes, which advocated the "gap theory," fundamentalists began a serious internal debate about the nature and chronology of creation.[3]

The first edition of the Scofield Bible (1909) was published only a few years before World War I, a war that destroyed a cultural optimism that had viewed the world as entering a new era of peace and prosperity; then the post-World War II era witnessed the creation of a homeland for Jews in Palestine. Thus, Scofield's premillennialism seemed prophetic. "At the popular level, especially, many people came to regard the dispensationalist scheme as completely vindicated."[4] Sales of the Reference Bible exceeded two million copies by the end of World War II.[5]

The Scofield Reference Bible promoted dispensationalism, the belief that between creation and the final judgment there would be seven distinct eras of God's dealing with man and that these eras are a framework for synthesizing the message of the Bible.[6] Largely through the influence of Scofield's notes, many fundamentalist Christians in the United States adopted a dispensational theology. Scofield's notes on the Book of Revelation are a major source for the various timetables, judgments, and plagues elaborated on by popular religious writers such as Hal Lindsey, Edgar C. Whisenant, and Tim LaHaye;[7] and in part because of the success of the Scofield Reference Bible, twentieth-century American fundamentalists placed greater stress on eschatological speculation.

The Scofield Bible has had a significant influence on the Christian Zionist movement. The work states that antisemitism is a sin. Citing Genesis 12:3 - "I will bless them that bless thee" - Scofield argued that "The man or nation that lifts a voice or hand against Israel invites the wrath of God."[8]

Later editions

[edit]

The 1917 Scofield Reference Bible notes are now in the public domain, and the 1917 edition is "consistently the best selling edition of the Scofield Bible" in the United Kingdom and Ireland.[9] In 1967, Oxford University Press published a revision of the Scofield Bible with a slightly modernized KJV text, and a muting of some of the tenets of Scofield's theology.[10] Recent editions of the KJV Scofield Study Bible have moved the textual changes made in 1967 to the margin.[11] The Press continues to issue editions under the title Oxford Scofield Study Bible, and there are translations into French, German, Spanish, and Portuguese. For instance, the French edition published by the Geneva Bible Society is printed with a revised version of the Louis Segond translation that includes additional notes by a Francophone committee.[12]

In the 21st century, Oxford University Press published Scofield notes to accompany six additional English translations.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ The title page listed seven "consulting editors": Henry G. Weston, James M. Gray, W.J. Erdman, A.T. Pierson, W. G. Moorehead, Elmore Harris, and A. C. Gaebelein. "Just what role these consulting editors played in the project has been the subject of some debate. Apparently Scofield only meant to acknowledge their assistance, though some have speculated that he hoped to gain support for his publication from both sides of the millenarian movement with this device." Ernest Sandeen, The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800-1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 224.

- ^ Gordon Campbell, Bible: The Story of the King James Version, 1611-2011 (Oxford University Press, 2010), 26. The Scofield Bible was the predecessor of the "very successful marketing trend" of orienting Bible study tools to average laymen. Mangum & Sweetnam, 172.

- ^ Ussher's dates and the gap theory are "not completely congruous with one another," Ussher's dates implying a young earth, and the "gap" between the first two verses of Genesis—as well as Scofield's allowance of the day-age theory—suggesting the possibility of an old earth. Mangum & Sweetnam, 97.

- ^ Mangum & Sweetnam, 179.

- ^ Gaebelein, 11.

- ^ Magnum & Sweetnam, 188-195. "Historically speaking, The Scofield Reference Bible was to dispensationalism what Luther's Ninety-five Theses was to Lutheranism, or what Calvin's Institutes was to Calvinism." (195).

- ^ Mangum & Sweetnam, 218.

- ^ "The Scofield Bible—The Book That Made Zionists of America's Evangelical Christians". Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

- ^ Mangum & Sweetnam, 201. The text of King James Version remains under Crown Copyright.

- ^ Mangum & Sweetnam, 201. "The continuing popularity of the 1917 notes may reflect the preference of the purchasers for the original and full-strength Scofield." Mangum & Sweetnam suggest the popularity of the 1917 edition may also reflect a strong commitment to the KJV translation. Scofield was accused of promoting "two ways of salvation" with a dispensation of works before the death and resurrection of Christ and a dispensation of grace afterwards. In the revision of 1967, Scofield's note on John 1:17 "was rewritten, and now seemed to say the opposite of Scofield's original." Gordon Campbell, Bible: The Story of the King James Version, 1611-2011 (Oxford University Press, 2010), 246-47.

- ^ The Scofield Study Bible III, KJV: How to use this study Bible. Oxford University Press. 2003. ISBN 9780199723874. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ Mangum & Sweetnam, 202-03. Some of the notes have also appeared in Korean and Polynesian.

- ^ Campbell, Bible, 248.

Further reading

[edit]- Arno C. Gaebelein, The History of the Scofield Reference Bible (Our Hope Publications, 1943)

- William E. Cox, Why I Left Scofieldism (Phillipsburg, N.J.: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., 1975) ISBN 0-87552-154-1

- R. Todd Mangum and Mark S. Sweetnam, The Scofield Bible: Its History and Impact on the Evangelical Church (Colorado Springs: Paternoster Publishing, 2009)

- Donald Harman Akenson, The Americanization of the Apocalypse: Creating America's Own Bible (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023)

External links

[edit]- The KJV Scofield® Study Bible III 2003

- The Scofield reference Bible. The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments 1917

- Scofield Reference Bible Notes at Wikisource

- Searchable text of the 1917 version of the Scofield Reference Bible reference notes.