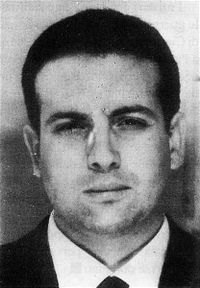

Stefano Bontade

Stefano Bontade | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Stefano Bontate 23 April 1939 Palermo, Italy |

| Died | 23 April 1981 (aged 42) Palermo, Italy |

| Cause of death | Multiple gunshots wounds |

| Body discovered | In a car |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Other names | Principe di Villagrazia, Il Falco |

| Allegiance | Sicilian Mafia |

Stefano Bontade (23 April 1939 – 23 April 1981), born Stefano Bontate, was a powerful member of the Sicilian Mafia. He was the boss of the Santa Maria di Gesù Family in Palermo. He was also known as the Principe di Villagrazia (Prince of Villagrazia) − the area of Palermo he controlled − and Il Falco (the Falcon).[1] He had links with several powerful politicians in Sicily, and with prime minister Giulio Andreotti. In 1981 he was killed by the rival faction within Cosa Nostra, the Corleonesi. His death sparked a brutal Mafia War that left several hundred mafiosi dead.

Early life and Mafia career

[edit]Bontade was born Stefano Bontate on 23 April 1939 in Palermo, Sicily, into a family of Mafiosi. His father and grandfather were both powerful Mafia bosses in the area Villagrazia, Santa Maria di Gesù and Guadagna, which were rural districts before they were absorbed into the city of Palermo in the 1960s. Stefano's father, Francesco Paolo Bontade, was one of the most powerful mafiosi on the island and a pallbearer at the funeral of Mafia boss Calogero Vizzini – one of the most influential Mafia bosses of Sicily after World War II until his death in 1954.[2][3]

Stefano Bontade and his brother Giovanni Bontade, who would become a lawyer, studied at a Jesuit college. In 1964, at the age of 25, Stefano Bontade became the boss of the Santa Maria di Gesù Mafia Family when his father, Don Paolino Bontade, stepped down because of ill-health (he suffered from diabetes). The Mafia went through difficult times at that moment. A bloody internal struggle (known as the First Mafia War) culminated in the Ciaculli Massacre in June 1963 that killed seven police and military officers sent to defuse a bomb in an abandoned Alfa Romeo Giulietta after an anonymous phone call.[4]

The Ciaculli Massacre changed the Mafia war into a war against the Mafia. It prompted the first concerted anti-mafia efforts by the state in post-war Italy.[4] Within a period of ten weeks 1,200 mafiosi were arrested, many of whom would be kept out of circulation for five or six years. The Sicilian Mafia Commission was dissolved and those mafiosi who had escaped arrest went into exile abroad or had to hide out in Italy. In 1968, 114 went on trial, though only ten minor figures would be convicted of anything. Bontade nonetheless managed to remain a highly important figure within Cosa Nostra, and he was also one of those responsible for ordering the death of Michele Cavataio by sending two of his soldiers, Gaetano Grado and Emanuele D'Agostino, to kill him in the Viale Lazio massacre.[4][5]

After the killing of Pietro Scaglione – Chief Prosecutor of Palermo – on 6 May 1971, the police rounded up the known Mafia bosses. Bontade was arrested in 1972 and he was sentenced to three years in the second Trial of the 114 in July 1974, but the sentence was annulled on appeal. Nevertheless, Bontade was sent in banishment to Qualiano (in the province of Naples). The policy of banishing mafiosi to other areas in Italy backfired, because they were able to establish contacts outside the island as well. Bontade, for instance, linked up with Giuseppe Sciorio of the Maisto-clan of the Camorra, who would be initiated in Cosa Nostra.

Cigarette smuggling and heroin trafficking

[edit]Bontade and other banished mafiosi managed to get into the market of international cigarette smuggling by imposing first their protection, and later their involvement, upon the smugglers in Naples (who were connected with the Camorra) and Palermo who had been running this activity since the 1950s. For instance, a thriving smuggler such as Nunzio La Mattina, was initiated into the Santa Maria di Gesù Family.[6] It was only through cigarette smuggling and subsequently heroin trafficking that many mafiosi were able to survive the difficult period after the Ciaculli Massacre. But then they started to accumulate large amounts of money rapidly. According to pentito Antonio Calderone, Bontade used to say that fortunately Tommaso Spadaro did a little bit of cigarette smuggling and gave him part of the profits, "because they were starving to death."[7] Spadaro was related to Bontade, being a godfather to one of his children.[8]

Bontade was closely linked to the Spatola-Inzerillo-Gambino network. This network and other Sicilian suppliers dominated heroin trafficking from the mid-1970s until the mid-1980s when US and Italian law enforcement were able to significantly reduce the heroin supply of the Sicilian Mafia (the so-called Pizza Connection). The Bontade-Spatola-Inzerillo traffickers supplied the Gambino Family – through John Gambino – in New York with heroin that was refined in laboratories on the island from Turkish morphine base.[9] According to Giovanni Falcone, the investigating magistrate, the group had made about US$600 million. The proceeds were re-invested in real estate. Rosario Spatola, who in his youth peddled watered milk in the streets of Palermo, became Palermo's largest building contractor and biggest taxpayer of Sicily.[10]

Francesco Marino Mannoia, who belonged to the Santa Maria di Gesù Family and who was highly sought after by all Mafia families for his skills in chemistry, after becoming a pentito recalled having refined at least 1,000 kilograms of heroin for Bontade. Marino Mannoia, who had been close to Bontade, decided to cooperate with the Italian state in October 1989, after his brother was killed by the Corleonesi (and subsequently saw his mother, his sister and his aunt killed as well). According to Marino Mannoia, Sicilian-born banker Michele Sindona laundered the proceeds of heroin trafficking for the Bontade-Spatola-Inzerillo-Gambino network.

Mattei affair

[edit]In May 1994 Mafia turncoat Buscetta declared that Bontade had been involved in the murder of Enrico Mattei, the president of Italy's state-owned oil and gas conglomerate ENI. Mattei was killed in 1962 at the request of the American Cosa Nostra because his oil policies had damaged important American interests in the Middle East.[11] The American Mafia in turn was possibly doing a favour to the large oil companies. Buscetta claimed that the killing was organized by Bontade, Salvatore Greco "Ciaschiteddu", and Giuseppe Di Cristina on the request of Angelo Bruno, a Sicilian-born Mafia boss from Philadelphia.[11] Buscetta also claimed that the journalist Mauro De Mauro was killed in September 1970 on the orders of Bontade because of his investigations into the death of Mattei.[12] Buscetta said that Bontade organized De Mauro's kidnapping, because the journalist's investigations into the death of Mattei came very close to the Mafia, and Bontade's own role in the affair.[11] Other pentiti said that De Mauro was kidnapped by Emanuele D'Agostino, a mafioso from Bontade's Santa Maria di Gesù Family.[13] De Mauro's body has never been found. Marino Mannoia testified that he had been ordered by Bontade in 1977 or 1978 to dig up several bodies, including De Mauro's, and dissolve them in acid.[14]

Sindona's bogus kidnapping

[edit]Michele Sindona was in charge of one of the biggest banks in the United States, the Franklin National Bank, which controlled the Vatican foreign investments, and was a major sponsor of the Christian Democracy party (DC – Democrazia Cristiana), according to a 1982 parliamentary inquiry. The inquiry also pointed out Sindona's relationship with Giulio Andreotti – who served as the prime minister of Italy seven times – and who once defined Sindona as the "rescuer of the lira".[15] After Sindona's banks went bankrupt in 1974, Sindona fled to the US. In July 1979, Sindona ordered the murder of Giorgio Ambrosoli, a lawyer appointed to liquidate his failed Banca Privata Italiana. At the same time the Mafia killed police superintendent Boris Giuliano, who was investigating the Mafia's heroin trafficking and had contacted Ambrosoli two weeks before to compare investigations.[15]

While under indictment in the US, Sindona staged a bogus kidnapping in August 1979 to conceal a mysterious 11-week trip to Sicily before his scheduled fraud trial. Bontade's brother in law Giacomo Vitale (a freemason, like Bontade) was one of those who organised Sindona's travel. The real purpose of the staged kidnapping was to issue lightly disguised blackmail notes to Sindona's past political allies – among them Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti – to engineer the rescue of his banks and recover Cosa Nostra's money. The plot failed and after his "release" Sindona surrendered to the FBI.[15] The Sindona affair showed the close links between the Mafia and certain important businessmen, freemasons and politicians. In the aftermath of the investigations, it appeared that many of them were connected through the secret P2 lodge (Propaganda Due) of Licio Gelli.[16]

Political connections

[edit]Stefano Bontade had links with the Christian Democracy politician Salvo Lima and Antonio Salvo and Ignazio Salvo, two wealthy mafia-cousins from Salemi who acted as the tax collectors on the island (tax collection was contracted out by the government).[17] Through them Bontade had access to Giulio Andreotti. Italy's highest court, the Court of Cassation, ruled in October 2004 that Andreotti had "friendly and even direct ties" with top men in the so-called moderate wing of Cosa Nostra, Stefano Bontade and Gaetano Badalamenti, favoured by the connection between them and Lima. According to pentito Francesco Marino Mannoia, Andreotti contacted Bontade to try to prevent the Mafia from killing DC-politician Piersanti Mattarella. Mattarella became the President of the autonomous Sicilian Region in 1978 and wanted to clean up the government's public contracts racket that benefitted Cosa Nostra. Bontade and other mafiosi felt betrayed by Mattarella (his father Bernardo Mattarella was rumored to be associated with the Mafia, but no accusations against him were proven before any court of law).[18]

Andreotti's attempt failed. After the murder of Mattarella on 6 January 1980, Andreotti again contacted Bontade to try to straighten things out.[18] However, according to Marino Mannoia, Bontade told Andreotti that "we are in charge in Sicily, and unless you want the whole DC canceled out, you do as we say."[19] In the mid-1970s, Stefano Bontade was also in touch with Silvio Berlusconi (Berlusconi was prime minister from 1994–1995, 2001–2006, and from 2008 to 2011). At the time, Berlusconi was still just a wealthy real estate developer and had started his private television empire.[20][21][22] Bontade visited Berlusconi's villa in Arcore on the outskirts of Milan, according to Antonino Giuffrè, a mafioso who was a key aide to Mafia kingpin Bernardo Provenzano but turned state witness after his arrest in April 2002. Bontade's contact at Arcore was the late Vittorio Mangano, a convicted mafioso who used to be a stable manager there. Giuffrè said: "When Vittorio Mangano got the job in the Arcore villa, Stefano Bontade and some of his close aides used to meet Berlusconi using visits to Mangano as an excuse."[22] Berlusconi's lawyer dismissed Giuffrè's testimony as "false" and an attempt to discredit Berlusconi and his party.[20]

Sicilian Mafia Commission

[edit]In 1970, the Sicilian Mafia Commission was revived. It consisted of ten members but would initially be ruled by a triumvirate consisting of Gaetano Badalamenti, Stefano Bontade and the Corleonesi boss Luciano Leggio, although it was Salvatore Riina who actually would represent the Corleonesi.[2][23] At the time Bontade was emerging as one of the Sicilian Mafia's acknowledged leaders. Young, rich, personable, intelligent and judicious, as well as the son of a renowned Mafia boss, it all made Bontade an undisputed candidate to sit on the Sicilian Mafia Commission. In 1975, the full Commission was reconstituted under the leadership of Badalamenti. The Mafia Commission was meant to settle disputes and keep the peace, but Leggio and his stand-in and successor, Salvatore Riina, were plotting to decimate the Palermo clans, including Bontade and Bontade's ally, Salvatore Inzerillo. At the close of 1978, the leadership of the Sicilian Mafia changed. Gaetano Badalamenti was expelled from the Commission and Michele Greco replaced him. This marked the end of a period of relative peace and signified a major change in the Mafia itself. Greco was actually allied with Salvatore Riina, and he subsequently used his position to lure many more of Bontade's friends to their deaths in the subsequent Mafia War.[24] Historically, the Greco clan from Croceverde Giardini had been at odds with the Greco clan of Ciaculli led by Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco, of whom Bontade was an ally.

Second Mafia War

[edit]The Second Mafia War raged from 1981 to 1984. In fact, two wars were being waged simultaneously by the Corleonesi clan. Riina had secretly formed an alliance of mafiosi in different families, cutting across clan divisions, in defiance of the rules concerning loyalty in Cosa Nostra. This secretive inter-family group became known as the Corleonesi. They slaughtered the ruling families of the Palermo Mafia to take control of the organisation, while waging a parallel war against Italian authorities and law enforcement to intimidate and prevent effective investigations and prosecutions.

The Corleonesi initiated the war against the coalition led by Bontade and Badalamenti to try to control heroin trafficking. They began by first eliminating Bontade's allies outside Palermo, including Giuseppe Di Cristina and Giuseppe Calderone, the bosses of Riesi and Catania, in an effort to isolate the Palermitan bosses. Despite the larger economic means and the wider international network, the Bontade-Spatola-Inzerillo-Badalamenti network was unable to withstand the overmuch violence of the Corleonesi. The most important members of the Inzerillo, Spatola and Gambino clans were arrested in March 1980 for heroin trafficking, which undermined Bontade's position significantly. In 1981, in an attempt to control the situation, Bontade plotted Totò Riina's killing but the latter learned all through Michele Greco, a former ally of Bontade's.

Assassination

[edit]

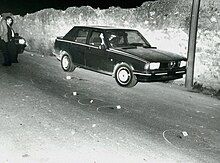

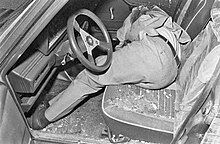

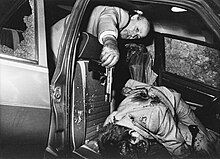

On the evening of April 23, 1981, while driving home from his 42nd birthday party in Palermo, Bontate was killed;[1] this happened at a red light in via Aloi while sitting in his Alfa Romeo Giulietta 2000. At 11:30 pm, he was reached by a motorcycle driven by Giuseppe Lucchese with behind him Giuseppe Greco also known as Scarpuzzedda ("little shoe") who shot him to death with an AK-47, leaving him unrecognizable. Three weeks later, Bontade's close ally Salvatore Inzerillo was shot to death outside the house of his mistress by a group of hitmen armed with the same rifle.[3][25][26]

Many of Bontade and Inzerillo's friends, fellow mafiosi and relatives were cut down in the following months to prevent them from avenging the death of their bosses. One of Bontade's close friends was Tommaso Buscetta, who subsequently became a pentito (collaborating witness) after he was arrested in Brazil in October 1983.[27] Salvatore Contorno, one of Bontade's trusted aides, followed Buscetta's example. They were the key witnesses that enabled prosecuting magistrates Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino and the Antimafia pool to successfully prosecute the Mafia in the Maxi Trial in the mid-1980s.

References

[edit]- ^ a b (in Italian) Trent'anni fa l'assassinio di Bontade, La Repubblica, 23 April 2011

- ^ a b Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 337-38

- ^ a b Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 52-54

- ^ a b c Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 103

- ^ (in Italian) La strage di viale Lazio spiegata dal pentito chiave, LiveSicilia, 28 April 2009

- ^ Gambetta, The Sicilian Mafia, p. 231

- ^ Paoli, Mafia Brotherhoods, p. 148-49

- ^ Gambetta, The Sicilian Mafia, p. 312

- ^ Sterling, Octopus, p. 199-201

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 37

- ^ a b c (in Italian) Buscetta: 'Cosa nostra uccise Enrico Mattei', La Repubblica, 23 May 1994

- ^ (in Italian) Quando Buscetta riapri' il caso, La Repubblica, 22 June 1995

- ^ (in Italian) Il debutto in aula dell'ex padrino, La Repubblica, 19 February 2011

- ^ (in Italian) De Mauro, la verità di Mannoia; Sciolsi il suo corpo nell' acido', La Repubblica, 12 2006

- ^ a b c Sterling, Octopus, p. 190-202

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 37-42

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 148/310/383-84

- ^ a b Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 423-24

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 391

- ^ a b Who Are You Going To Believe?, Time Magazine, 12 January 2003

- ^ Berlusconi implicated in deal with godfathers, The Guardian, 5 December 2002

- ^ a b Mafia supergrass fingers Berlusconi by Philip Willan, The Observer, 12 January 2003

- ^ Sterling, Octopus, p. 112

- ^ uccisi a tavola i nemici. i corpi sciolti nell'acido - archiviostorico.corriere.it

- ^ Dickie, Cosa Nostra, p. 373-75

- ^ Sterling, Octopus, p. 209

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 108-09

Bibliography

[edit]- Dickie, John (2004). Cosa Nostra. A history of the Sicilian Mafia, London: Coronet, ISBN 0-340-82435-2

- Gambetta, Diego (1993).The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection, London: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-80742-1

- Paoli, Letizia (2003). Mafia Brotherhoods: Organized Crime, Italian Style, New York: Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-515724-9

- Sterling, Claire (1990). Octopus. How the long reach of the Sicilian Mafia controls the global narcotics trade, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-73402-4

- Stille, Alexander (1995). Excellent Cadavers. The Mafia and the Death of the First Italian Republic, New York: Vintage ISBN 0-09-959491-9