Sanitarium (video game)

| Sanitarium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | DreamForge Intertainment DotEmu (iOS, Android) |

| Publisher(s) | ASC Games DotEmu (iOS, Android) |

| Designer(s) | Michael Nicholson |

| Programmer(s) | Chad Freeman |

| Artist(s) | Eric Ranier Rice Michael Nicholson Brian Schutzman |

| Writer(s) | Michael Nicholson Chris Pasetto |

| Composer(s) | Stephen Bennett Jamie McMenamy |

| Platform(s) | Windows, iOS, Android |

| Release | WindowsiOS, Android October 29, 2015[2] |

| Genre(s) | Point-and-click adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single player |

Sanitarium is a psychological horror point-and-click adventure video game that was originally released for Microsoft Windows. It was developed by DreamForge Intertainment and published by ASC Games in 1998.[3] It was a commercial success, with sales of around 300,000 units. In 2015, it was ported to iOS[4] and Android devices.[5]

Plot

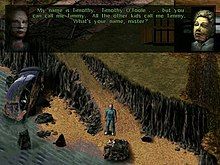

[edit]After a car accident knocks him unconscious, a man awakens from a coma, his face fully bandaged, to find that he has been admitted to a dilapidated sanitarium and that he cannot remember who he is or where he came from, or how he came to be there.[6] He gradually remembers his first name, Max.

As he delves into the asylum's corridors in search of answers, Max finds himself transported to various obscure and otherworldly locations: a town inhabited only by malformed children and overseen by a malevolent alien entity known as "Mother", a demented circus surrounded by an endless ocean and terrorized by a squid-like individual, an alien hive populated by cyborg insects, and an Aztec village devastated by the return of the god Quetzalcoatl. Max himself is often subsumed into a different identity in these locations, such as Sarah, his younger sister who died in childhood from a disease, and Grimwall, the four-armed Cylopsian hero of a favorite comic book. Between each episode, Max returns to the asylum grounds, blending real and unreal, each time closer to regaining his memory and unraveling the truth surrounding the mysterious Dr. Morgan, head of the asylum. He confronts his feelings of guilt surrounding the death of Sarah and his drive to save other children.

Max remembers that he was working at the Mercy Foundation on a cure for the deadly DNAV virus, which primarily kills children, but Dr. Jacob Morgan, the head of the foundation and Max's med school colleague, cut funding and staff for his research. Morgan denied that Max was close to a cure and said resources were better spent perfecting the existing Hope drug, which slows the progress of DNAV but does not cure it, but Max accused him of favoring the Hope drug because it is more profitable. Max realizes that he is in a coma and everything he has experienced since the accident, including the episodes in the asylum, has been a product of his imagination. He uses Dr. Morgan as the focus of his frustrations, visualizing that Morgan has given him an injection which will kill him if he does not awaken and remove his intravenous line quickly. This allows Max to break out of the coma. He is happily reunited with his wife.

Months later, Max's wife gives birth to their first child, and the Mercy Foundation publishes Max's cure for the DNAV virus. Morgan resigns from the Mercy Foundation and is prosecuted when it is discovered that Max's car was tampered with prior to his accident in an apparent effort to prevent the cure from being released. Max becomes the new head of the Mercy Foundation.

Gameplay

[edit]

The game uses an isometric perspective and a non-tiled 2D navigational system. Each world and setting carries a distinct atmosphere that presents either the real world, the imaginary world, or a mix of both of the main protagonist. In many cases, it is unclear to the player if the world the character is currently in is real or a product of Max's own imagination. This indistinction underlines much of the horror portrayed in the game.[7][8]

The game is separated into different levels or "chapters" with each having a different style and atmosphere. The player must find clues, solve puzzles and interact with other characters to reach a final challenge, where the player must reach the end of a path while avoiding obstacles. Failure to do so (by, for instance, getting killed) causes the player to be transported back to the beginning of the path without losing progress, thus a game over in this game is non-existent. When the player reaches the end of the path, a cinematic is played and the game proceeds to the next chapter.[7][8]

Release

[edit]The game was published by ASC Games. ASC executive producer Travis Williams explained, "The whole point of this game is to freak you out, and it's actually the first one I've ever come across that really does it. And that's why I said, 'God, we've got to pick this one up.'"[6]

Reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| GameRankings | (PC) 83%[9] (iOS) 75%[10] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Adventure Gamers | (PC) |

| AllGame | (PC) |

| CNET Gamecenter | (PC) 7/10[13] |

| Computer Games Strategy Plus | (PC) |

| Computer Gaming World | (PC) |

| EP Daily | (PC) 8.75/10[15] |

| Game Informer | (PC) 6.5/10[16] |

| GameRevolution | (PC) B+[17] |

| GameSpot | (PC) 8.2/10[18] |

| IGN | (PC) 7/10[19] |

| Next Generation | (PC) |

| PC Gamer (US) | (PC) 89%[21] |

| TouchArcade | (iOS) |

The PC and iOS versions received favorable reviews according to the review aggregation website GameRankings.[9][10] Next Generation said that the former version was "still vastly different and thoroughly entertaining. If only more companies would take gaming into as different a direction, our jobs would be a lot more interesting."[20]

The PC version was commercially successful. According to Mike Nicholson of DreamForge, the game sold roughly 300,000 units.[23] Chris Kellner of DTP Entertainment, which handled the same PC version's German localization, reported its lifetime sales between 10,000 and 50,000 units in the region.[24]

According to PC Accelerator, the PC version was a "critical success" that helped to raise DreamForge Intertainment's profile as a company.[25]

Awards

[edit]The PC version won the "Best Adventure" award, tied with Grim Fandango, at Computer Gaming World's 1999 Premier Awards. The staff wrote that the game "came from out of nowhere to provide the creepiest, most compelling, and best-told story of the year, bar none".[26] Computer Games Strategy Plus' Best of 1998 Awards, the fifth annual PC Gamer Awards, GameSpot's Best and Worst of 1998 Awards, IGNPC's Best of 1998 Awards and the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences' (AIAS) 2nd Annual Interactive Achievement Awards all nominated the same PC version as the best adventure game of 1998, but eventually lost these awards to Grim Fandango.[27][28][29][30][31] The staff of PC Gamer remarked that the same PC version has beautiful graphics, interesting characters, and well-designed puzzles.[30]

The game was also a nominee for GameSpot's "Best Story" and AIAS' "Outstanding Achievement in Character or Story Development", which were ultimately awarded to StarCraft and Pokémon Red and Blue, respectively.[32][33]

Legacy

[edit]In 2013, a programmer from the Sanitarium development team announced a project on Kickstarter called Shades of Sanity that was touted as the spiritual successor to Sanitarium.[34] The project failed to attain funding.[35] In 2015, a Kickstarter-funded adventure game called Stasis was released by a South African independent studio, The Brotherhood. It has been compared to Sanitarium.[36][37][38]

On October 29, 2015, Dotemu released an iOS port of the game with touchscreen controls, dynamic hint system, achievements and automatic save system.[4]

In 2011, Adventure Gamers named the PC version the 36th-best adventure game ever released.[39]

On August 1, 2022, ScummVM added support for playing Sanitarium using the original Windows game files, enabling it to be played on the various platforms ScummVM itself supports.[40]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gentry, Perry (April 21, 1998). "When's That Game Coming Out?". CNET Gamecenter. CNET. Archived from the original on August 17, 2000. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ Priestman, Chris (October 29, 2015). "Out now: Prep for Halloween with classic horror adventure game Sanitarium". Pocket Gamer. Steel Media Ltd. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Pasetto, Chris (December 4, 1998). "Postmortem: DreamForge's Sanitarium". Game Developer. Informa. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "Sanitarium". App Store (iOS/iPadOS). Apple Inc. Archived from the original on November 29, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ "Sanitarium". Google Play. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ a b "NG Alphas: Sanitarium". Next Generation. No. 38. Imagine Media. February 1998. pp. 94–95. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c Green, Jeff (September 1998). "Crazy, Man (Sanitarium Review)" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 170. Ziff Davis. pp. 238–39. Archived from the original on August 16, 2000. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Delgado, Francisco (February 1999). "Sanitarium - Genial Locura" [Sanitarium - Crazy Genius]. Micromanía (in Spanish). No. 49. Madrid, Spain: Axel Springer SE. pp. 92–95.

- ^ a b "Sanitarium for PC". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "Sanitarium for iOS (iPhone/iPad)". GameRankings. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ Michaud, Rob (September 11, 2003). "Sanitarium review (PC)". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ House, Michael L. "Sanitarium (PC) - Review". AllGame. All Media Network. Archived from the original on November 16, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ Dembo, Arinn (July 9, 1998). "Sanitarium (PC)". Gamecenter. CNET. Archived from the original on August 16, 2000. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ Altman, John (June 20, 1998). "Sanitarium". Computer Games Strategy Plus. Strategy Plus, Inc. Archived from the original on December 18, 2002.

- ^ Flower, Zoe (February 4, 1999). "Sanitarium (PC)". The Electric Playground. Greedy Productions Ltd. Archived from the original on May 2, 1999. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ Bergren, Paul (July 1998). "Sanitarium (PC)". Game Informer. No. 63. FuncoLand.

- ^ Hubble, Calvin (August 1998). "Sanitarium - PC Review". GameRevolution. CraveOnline. Archived from the original on February 20, 2004. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ Coffey, Robert (June 4, 1998). "Sanitarium Review (PC)". GameSpot. Fandom. Archived from the original on January 4, 2005. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ Bates, Jason (August 12, 1998). "Sanitarium (PC)". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on January 7, 2023. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Sanitarium (PC)". Next Generation. No. 44. Imagine Media. August 1998. p. 88. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ Poole, Stephen (August 1998). "Sanitarium". PC Gamer. Vol. 5, no. 8. Imagine Media. Archived from the original on February 26, 2000.

- ^ Musgrave, Shaun (December 1, 2015). "'Sanitarium' Review – I Think I'm A Banana Tree". TouchArcade. TouchArcade.com, LLC. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- ^ Mason, Graeme (September 2014). "The Making of: Sanitarium". Retro Gamer. No. 132. Imagine Publishing. pp. 88–91.

- ^ "The Lounge: Interview with DTP". The Inventory. No. 10. Just Adventure. November 2003. pp. 20–23. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006.

- ^ "Developer Spotlight: Dreamforge Entertainment". PC Accelerator. No. 9. Imagine Media. May 1999. p. 121. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ CGW staff (April 1999). "Computer Gaming World's 1999 Premier Awards (Best Adventure)" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 177. Ziff Davis. p. 96. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ IGN staff (January 29, 1999). "IGNPC's Best of 1998 Awards". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on April 4, 2002. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ GameSpot staff (1999). "The Best & Worst of 1998 (Adventure Game of the Year - Nominees)". GameSpot. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on October 2, 2000. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ "Second Interactive Achievement Awards: Personal Computer". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on November 4, 1999.

- ^ a b PC Gamer staff. "The Fifth Annual PC Gamer Awards". PC Gamer. Vol. 6, no. 3. Imagine Media. pp. 64, 67, 70–73, 76–78, 83–84, 86–87.

- ^ CGSP staff (February 11, 1999). "The Best of 1998 (Adventure Game of the Year)". Computer Games Strategy Plus. Strategy Plus, Inc. Archived from the original on February 10, 2005. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ GameSpot staff (1999). "The Best & Worst of 1998 (Best Story)". GameSpot. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on October 5, 2000. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ "Second Interactive Achievement Awards: Craft Awards". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on October 11, 1999.

- ^ Smith, Adam (August 19, 2013). "Back to the Sanitarium: Shades of Sanity". Rock Paper Shotgun. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ "Shades of Sanity Psychological Horror Game". Kicktraq. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Matulef, Jeffrey (December 3, 2013). "Isometric point-and-click horror adventure Stasis awakens on Kickstarter". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ Meer, Alec (May 19, 2014). "Sanitawesomium: STASIS Isn't Standing Still". Rock Paper Shotgun. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ Klepek, Patrick (September 2, 2015). "Stasis Shows How Spooky A Point-And-Click Adventure Can Be". Kotaku. G/O Media. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ^ AG staff (December 30, 2011). "Top 100 All-Time Adventure Games". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012.

- ^ "ScummVM 2.6.0 or: Insane Escapism". ScummVM. August 1, 2022. Archived from the original on August 2, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Sanitarium at MobyGames

- Sanitarium at IMDb

- 1990s horror video games

- 1998 video games

- Android (operating system) games

- ASC Games games

- Dotemu games

- DreamForge Intertainment games

- DTP Entertainment games

- IOS games

- Point-and-click adventure games

- Psychological horror games

- ScummVM-supported games

- Single-player video games

- Video games about amnesia

- Video games developed in the United States

- Video games set in psychiatric hospitals

- Video games with isometric graphics

- Windows games