Harare

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

Harare | |

|---|---|

Capital city and province | |

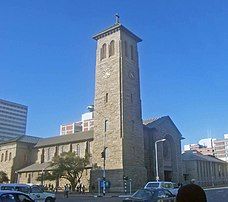

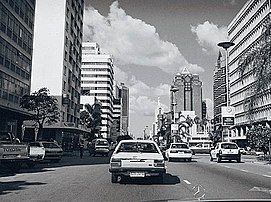

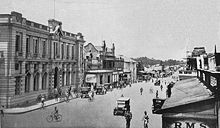

Left to right, from top: Harare skyline; Jacaranda trees lining Josiah Chinamano Avenue; Old Parliament House (front) and the Anglican Cathedral (behind); downtown Harare; New Reserve Bank Tower; Heroes' Acre monument | |

|

| |

| Nicknames: Sunshine City, H Town | |

Mottoes:

| |

Location of Harare Province in Zimbabwe | |

Map showing Harare in Zimbabwe | |

| Coordinates: 17°49′45″S 31°3′8″E / 17.82917°S 31.05222°E | |

| Country | Zimbabwe |

| Province | Harare |

| Founded | 12 September 1890 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1935 |

| Renamed Harare | 18 April 1982 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Jacob Mafume (CCC) |

| • Council | Harare City Council |

| Area | |

• Capital city and province | 982.3 km2 (379.3 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,490 m (4,890 ft) |

| Population (2022 census)[1] | |

• Capital city and province | 1,491,740 |

| • Density | 1,500/km2 (3,900/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,558,823 |

| • Metro | 1,603,201 |

| Demonym | Hararean |

| Time zone | UTC+02:00 (Central Africa Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | (Not Observed) |

| Area code | 242 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.645[4] Medium |

| Dialling code 242 (or 0242 from within Zimbabwe) | |

Harare (/həˈrɑːreɪ/ hə-RAR-ay),[5] formerly Salisbury, is the capital and largest city of Zimbabwe. The city proper has an area of 982.3 km2 (379.3 sq mi), a population of 1,849,600 as of the 2022 census[6] and an estimated 2,487,209 people in its metropolitan province.[6] The city is situated in north-eastern Zimbabwe in the country's Mashonaland region. Harare is a metropolitan province which also incorporates the municipalities of Chitungwiza and Epworth.[7] The city sits on a plateau at an elevation of 1,483 metres (4,865 feet) above sea level, and its climate falls into the subtropical highland category.

The city was founded in 1890 by the Pioneer Column, a small military force of the British South Africa Company, and was named Fort Salisbury after the British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury. Company administrators demarcated the city and ran it until Southern Rhodesia achieved responsible government in 1923. Salisbury was thereafter the seat of the Southern Rhodesian (later Rhodesian) government and, between 1953 and 1963, the capital of the Central African Federation. It retained the name Salisbury until 1982 when it was renamed Harare on the second anniversary of Zimbabwe's independence from the United Kingdom. The national parliament moved out of Harare upon completion of the New Parliament of Zimbabwe in Mount Hampden in April 2022.[8]

The commercial capital of Zimbabwe, Harare has experienced recent economic turbulence.[clarification needed] However, it remains an important centre of commerce and government, as well as finance, real estate, manufacturing, healthcare, education, art, culture, tourism, agriculture, mining and regional affairs.[9] Harare has the second-highest number of embassies in Southern Africa and serves as the location of the African headquarters of the World Health Organization, which it shares with Brazzaville.[10]

Harare has hosted multiple international conferences and events, including the 1995 All-Africa Games and the 2003 Cricket World Cup. In 2018, Harare was ranked as a Gamma World City. It is also home to Dynamos FC, the club with the most titles in Zimbabwean football.

History

[edit]Early colonial history

[edit]

The Pioneer Column, a military volunteer force of settlers organised by Cecil Rhodes, founded the city on 12 September 1890 as a fort.[11][12] They originally named the city Fort Salisbury after The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, then-Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and it subsequently became known simply as Salisbury. The Salisbury Polo Club was formed in 1896.[13] Salisbury was declared a municipality in 1897, and it became a city in 1935.[14]

At the time of the city's founding, its site and surroundings were poorly drained. The earliest development was on sloping ground along the left bank of a stream, in an area where the Julius Nyerere Way industrial road runs today. The first area to be fully drained was near the head of the stream and was named Causeway. Causeway is now the site of many important government buildings, including the Senate House and the Office of the Prime Minister. After the position was abolished in January 1988, the office was renamed for the use of the President.[15]

Salisbury was the seat of the British South Africa Company administrator and became capital of the self-governing British colony of Southern Rhodesia in 1923.[16]

Post-war period

[edit]In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, Salisbury expanded rapidly, boosted by its designation as the capital of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. This growth ushered in a wave of liberalism, investment and developmentalism from 1953 to 1963, transforming the city's skyline in the process.[17] This was accompanied by significant post-war immigration by White people, primarily from Great Britain, Southern Africa and, to a lesser extent, Southern Europe.[citation needed] The rapid rise of motor vehicle ownership and the investment in road development greatly accelerated the outward sprawl of suburbs such as Alexandra Park and Mount Pleasant. At the same time, mostly black suburbs like Highfield suffered from overcrowding as their populations boomed.[citation needed]

The optimism and prosperity of this period proved to be short-lived, as the Federation collapsed, which hindered the city's prosperity.[17][additional citation(s) needed]

1960s and 1970s

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2024) |

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was dissolved in 1963. Ian Smith's Rhodesian Front government declared Rhodesia independent from the United Kingdom on 11 November 1965, with Salisbury retained as the capital. Smith's Rhodesia later became the short-lived state of Zimbabwe Rhodesia; it was not until 18 April 1980 that the country was internationally recognised as independent as the Republic of Zimbabwe.[18]

Post-independence years

[edit]

The city initially boomed under a wave of optimism and investment that followed the country's independence in 1980. The name of the city was changed to Harare on 18 April 1982, the second anniversary of Zimbabwean independence, taking its name from the village near Harare Kopje of the Shona chief Neharawa, whose nickname was "he who does not sleep".[19] Before independence, "Harare" was the name of the black residential area now known as Mbare.[citation needed]

Significant investment in education and healthcare produced a confident and growing middle class, evidenced by the rise of firms such as Econet Global and innovative design and architecture, exemplified by the Eastgate Centre. A notable symbol of this era in Harare's history is the New Reserve Bank Tower, one of the city's major landmarks.[citation needed]

Harare was the location of several international summits during this period, such as the 8th Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement in September 1986 and the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting 1991.[20] The latter produced the Harare Declaration, dictating the membership criteria of the Commonwealth. In 1998, Harare was the host city of the 8th Assembly of the World Council of Churches.[21]

However, by 1992, Harare began to experience an economic downturn and the government responded by enacting neoliberal reforms. These policies provoked a boom in banking, finance and agriculture, but also led to significant job losses in manufacturing, thereby greatly increasing unemployment and income inequality. Domestic firms struggled to compete with foreign imports, leading to the collapse of several institutions, particularly in the textile industry.[17]

Economic difficulties and hyperinflation (1999–2008)

[edit]In the early 21st century, Harare was adversely affected by the political and economic crises that plagued Zimbabwe, particularly following the contested 2002 presidential election and 2005 parliamentary elections. The elected council was replaced by a government-appointed commission due to alleged inefficiency.[citation needed] Still, essential services such as rubbish collection and street repairs rapidly worsened, and are now virtually non-existent in poorer parts of the city.[citation needed] In May 2006, Zimbabwean newspaper Financial Gazette described the city in an editorial as a "sunshine city-turned-sewage farm".[22] In 2009, Harare was voted the world's toughest city to live in according to the Economist Intelligence Unit's livability poll, which factors in stability, healthcare, culture and environment, education, and infrastructure.[23] The situation was unchanged in 2011, according to the same poll.[24]

Operation Murambatsvina

[edit]In May 2005, the Zimbabwean government demolished shanties, illegal vending sites, and backyard cottages in Harare, Epworth and other cities in Operation Murambatsvina[25] ("Drive Out Trash"). It was widely alleged[weasel words] that the true purpose of the campaign was to make sure shantie towns would not develop in any urban areas that might favor the Movement for Democratic Change, and to reduce the likelihood of mass action against the government by driving people out of the cities.[citation needed] The government claimed its actions were necessitated by a rise of criminality and disease.[citation needed] This was followed by Operation Garikayi/Hlalani Kuhle (Operation "Better Living") a year later, which consisted of building poor-quality concrete housing.[citation needed]

Economic uncertainty

[edit]In late March 2010, Harare's Joina City Tower was finally opened after fourteen years of delayed construction, marketed as 'Harare's New Pride'.[26] Initially, uptake of space in the tower was low, with office occupancy at only 3% in October 2011.[27] By May 2013, office occupancy had risen to around half, with all the retail space occupied.[28][relevant?]

The Economist Intelligence Unit rated Harare as the world's least livable city (out of 140 surveyed) in February 2011,[29] rising to 137th out of 140 in August 2012.[30]

In March 2015, Harare City Council planned a two-year project to install 4,000 solar street lights, starting in the central business district, at a cost of $15,000,000.[31]

In November 2017, the biggest demonstration in the history of the Republic of Zimbabwe was held in Harare, which led to the forced resignation of the long-serving 93-year-old President of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, an event which was part of the first successful coup in Zimbabwe.[32][33]

Contemporary Harare

[edit]Since 2000, Harare has experienced periods of spectacular decline, particularly in the 2000s, but since the Great Recession it has stabilised and experienced significant population growth and uneven economic growth.[citation needed][clarification needed] There has nonetheless been substantial international investment and speculation in the city's financial and property markets. Development on the urban fringes of the city has occurred in areas such as Borrowdale, Glen Lorne, The Grange, Mount Pleasant Heights, as well as in the new suburbs of Hogerty Hill, Shawasha Hills, Bloomingdale and Westlea. Urban sprawl has also expanded into the nearby areas of Mount Hampden, Ruwa and Norton.[34] In addition, inner city areas such as Avondale, Eastlea, Belgravia, Newlands and Milton Park have seen increased gentrification driven by speculation from expat Zimbabweans. This speculation has also attracted other foreign buyers, resulting in high property prices and widespread rent increases.[35] Harare sustained the highest population increase and urban development of any major Zimbabwean city since 2000, with other cities such as Bulawayo, Gweru, and Mutare largely stagnating during the same period.[36]

Beginning in 2006, the city's growth extended into its northern and western fringes, beyond the city's urban growth boundary. Predictions that by 2025 the metropolitan area population will reach 4 to 5 million have sparked concerns over unchecked sprawl and unregulated development.[37][needs update] The concentration of real estate development in Harare has also come at the expense of other Zimbabwean cities such as Gweru and particularly Bulawayo, which is increasingly characterized by stagnation and high unemployment due to the collapse of many of its heavy industries. Today, Harare's property market remains highly priced, more so than regional cities such as Johannesburg and Cape Town.[citation needed] The top end of the market is completely dominated by wealthy or dual-citizen Zimbabweans (see Zimbabwean diaspora and Zimbabweans in the United Kingdom), Chinese and South African buyers.[34][37] Despite gentrification and speculation, the country's and city's unemployment rates remain high.[citation needed]

In 2020, Harare was classified as a Gamma city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[38]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1982 | 656,011 | — |

| 1992 | 1,189,103 | +81.3% |

| 2002 | 1,435,784 | +20.7% |

| 2012 | 1,485,231 | +3.4% |

| 2022 | 1,491,754 | +0.4% |

| Source:[39] | ||

As of 2012, Harare has a population of 2,123,132.[1] Over 90% of people in Harare are Shona-speaking people of African descent. Harare is also home to many Ndebele and Kalanga people as well. Roughly 25,000 white Zimbabweans also live in the Harare metro area.[40]

Geography

[edit]Topography

[edit]The city sits on one of the higher parts of the Highveld plateau of Zimbabwe at an elevation of 1,483 metres (4,865 feet). The original landscape could be described as a "parkland"[41] or wild place. The soils of Harare are varied: the northern and central areas largely have reddish brown, granular clay; some of the southern parts have gray-brown sand over pale, loamy sand or sandy loam.[42]

Suburbs

[edit]The City of Harare is divided into suburbs, outside of which are independent municipalities such as Epworth, Mount Hampden, Norton, Ruwa, and Chitungwiza, which are still located within the greater metropolitan province.[43]

The central business district of Harare is characterized by wide streets and a mix of historic, post-war, and modern buildings. Downtown sights include the Kopje Africa Unity Square, the Harare Gardens, the National Gallery, the August House parliamentary buildings, and the National Archives. Causeway, a road and sub-neighbourhood of central Harare, is a busy workaday area that acts as the city's "embassy row" (along with Belgravia to the north-east) in which numerous embassies, diplomatic missions, research institutes, and other international organizations are concentrated.[44] Additionally, many government ministries and museums, such as the Zimbabwe Museum of Human Sciences, are located here.[45]

Rotten Row is a sub-district of downtown Harare that begins at the intersection of Prince Edward Street and Samora Machel Avenue and runs to the flyover where it borders Mbare on Cripps Road.[46] Rotten Row was named after a road in London of the same name. The name "Rotten Row" is an altered form of the French phrase "Route du Roi," the King's Road.[47] It is known as Harare's legal district, home to the Harare Magistrate's Court, the city's central library, and the ZANU-PF building, along with numerous law offices.[46] The neighbourhood also lends its name to the eponymous book by Petina Gappah published in 2016.[48]

The northern and north-eastern suburbs of Harare are generally home to its more affluent residents, including former president Robert Mugabe, who lived in Borrowdale Brooke.[49] These northern suburbs are often referred to as "dales" because of the common suffix "-dale" found in some suburbs such as Avondale, Greendale, and Borrowdale.[citation needed] The dwellings are mostly low-density homes of 3 bedrooms or more, and these are usually occupied by families.[citation needed] Borrowdale in particular is home to some of the most extensive real estate developments in the city.[50] The north-western suburb of Emerald Hill is named so either due to the green colour of the tree-covered hill or its Irish connections — many of the roads in the suburb have Irish names, such as Dublin, Belfast, Wicklow, and Cork.[50]

To the east of Harare's city center, notable suburbs include Arcadia, Newlands, Arlington, and others. Newlands was named by Colin Duff, Zimbabwe's agricultural secretary in the 1920s. Arlington is a newer suburb adjacent to Harare International Airport and was previously owned by William Harvey Brown, a former mayor of Salisbury. Brown was originally from Iowa and joined the occupying British South Africa Company forces in the 1890s to collect specimens for the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.[50]

The southern portions of Harare have historically been more industrial areas, often home to most of its African population as well as some lower-class European-descended populations.[51] Willowvale, is perhaps best known for the 1988 Willowgate scandal, which implicated several members of the ZANU-PF party in a scheme where automobiles were illegally resold by various government officials.[citation needed] Harare's south-west also contains many high-density townships, which were set up by the government from the 1930s onwards. For example, Highfield, established in 1930, is the second-oldest high-density suburb in Harare. Highfield was created as a place for black workers to settle, providing labor for the industrial areas of Southerton and Workington.[50]

Climate

[edit]

Under the Köppen climate classification, Harare has a subtropical highland climate (Köppen Cwb), an oceanic climate variety. Because the city is situated on a plateau, its high altitude and cool south-easterly airflow cause it to have a climate that is cooler and drier than a tropical or subtropical climate.

The average annual temperature is 17.95 °C (64.3 °F), rather low for the tropics. This is due to its high altitude position and the prevalence of cool south-easterly airflow.[52]

There are three main seasons: a warm, wet summer from November to March/April; a cool, dry winter from May to August (corresponding to winter in the Southern Hemisphere); and a warm to hot, dry season in September/October. Daily temperature ranges are about 7–22 °C (45–72 °F) in July (the coldest month), about 15–29 °C (59–84 °F) in October (the hottest month) and about 16–26 °C (61–79 °F) in January (midsummer). The hottest year on record was 1914 with 19.73 °C (67.5 °F) and the coldest year was 1965 with 17.13 °C (62.8 °F).

The average annual rainfall is about 825 mm (32.5 in) in the southwest, rising to 855 mm (33.7 in) on the higher land of the northeast (from around Borrowdale to Glen Lorne). Very little rain typically falls during the period of May to September, although sporadic showers occur most years. Rainfall varies a great deal from year to year and follows cycles of wet and dry periods from 7 to 10 years long. Records begin in October 1890 but all three Harare stations stopped reporting in early 2004.[53]

The climate supports the natural vegetation of open woodland. The most common tree of the local region is the msasa or Brachystegia spiciformis whose wine-red leaves are most visible in the city in late August. Two introduced species of trees, the jacaranda and the flamboyant from South America and Madagascar respectively, were introduced during the colonial era and contribute to the city's colour palette with their lilac and red blossoms. The two species flower in October/November and are planted on alternating streets in the capital. Bougainvillea is prevalent in Harare as well. Some trees from Northern Hemisphere middle latitudes are also cultivated, including American sweetgum, English oak, Japanese oak and Spanish oak.[54]

| Climate data for Harare (1961–1990, extremes 1897–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.9 (93.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.0 (89.6) |

30.0 (86.0) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.8 (83.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

35.3 (95.5) |

33.5 (92.3) |

36.7 (98.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 26.2 (79.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.8 (83.8) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.3 (79.3) |

25.5 (77.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.6 (65.5) |

20.8 (69.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.3 (48.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

6.5 (43.7) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.3 (54.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 9.6 (49.3) |

8.0 (46.4) |

7.5 (45.5) |

4.7 (40.5) |

2.8 (37.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.1 (39.4) |

5.1 (41.2) |

6.1 (43.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 190.8 (7.51) |

176.3 (6.94) |

99.1 (3.90) |

37.2 (1.46) |

7.4 (0.29) |

1.8 (0.07) |

2.3 (0.09) |

2.9 (0.11) |

6.5 (0.26) |

40.4 (1.59) |

93.2 (3.67) |

182.7 (7.19) |

840.6 (33.09) |

| Average precipitation days | 17 | 14 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 16 | 82 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 77 | 72 | 67 | 62 | 60 | 55 | 50 | 45 | 48 | 63 | 73 | 62 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 217.0 | 190.4 | 232.5 | 249.0 | 269.7 | 264.0 | 279.0 | 300.7 | 294.0 | 285.2 | 231.0 | 198.4 | 3,010.9 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7.0 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 7.7 | 6.4 | 8.2 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization,[55] NOAA (sun and mean temperature, 1961–1990),[56] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (humidity, 1954–1975),[57] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[58] | |||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]This section may be unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. (July 2024) |

Harare is Zimbabwe's leading financial, commercial, and communications centre, as well as an international trade centre for tobacco, maize, cotton, and citrus fruits.[citation needed] Manufacturing of products including textiles, steel, and chemicals is also economically significant, as is the trade of precious minerals such as gold, diamonds and platinum.[citation needed] Early investor optimism following the inauguration of the Mnangagwa government in 2017 has since largely subsided due to the slow pace of reforms aimed at making Harare and Zimbabwe more business-friendly.[59] The economy suffered high inflation and frequent power outages in 2019, which further hampered investment, and the poor implementation of adequate monetary reforms alongside deficit reduction attempts had a similar effect.[citation needed] Although the government has repeatedly stressed its commitments to improving transparency, increasing the ease of doing business, and fighting corruption, progress remains limited under the Mnangagwa administration.[59]

Harare experienced a real estate boom in the 2000s and early 2010s, particularly in the wealthy northern suburbs, with prices rising dramatically over the last decade despite challenges in other sectors of the economy.[60] This boom was largely fueled by members of the Zimbabwean diaspora and by speculation, with investors hedging against the local currency.[60][34] However, the once-growing market began to cool off due to a 2019 hike in interest rates and the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving a number of projects unfinished.[61]

Another challenge to Harare's economy is the persistent emigration of highly educated and skilled residents to the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Ireland, South Africa and New Zealand, largely due to the economic downturn and political unrest.[62] The city's brain drain, almost unprecedented compared to other emerging markets,[citation needed] has led to declining numbers of local entrepreneurs, an overstretched and declining middle class, and a dearth of employment opportunities outside the informal and public sector.[62] In addition, the city's working-class residents are increasingly moving to nearby South Africa and Botswana, though they are readily replaced by less well-off rural migrants.[63] However, despite over a decade of neglect, the city's infrastructure and human capital still compares favourably with cities in other parts of Africa and Latin America.[citation needed] It remains to be seen whether the current government can entice its diverse and well-educated Zimbabwean diaspora, numbering some 4 to 7 million people, to invest in the economy, let alone consider returning.[64][62][65]

Shopping and retail

[edit]Locally produced art, handicrafts and souvenirs can be purchased at locations including Doon Estate, Uwminsdale, Avondale Market and Mbare Musika. Msasa Park and Umwinsdale in particular host a number of galleries that produce high-quality Shona soapstone sculptures and textiles, such as Patrick Mavros Studios, which has another gallery in Knightsbridge, London.[66] International brands are generally less common in Harare than in European cities. However, conventional and luxury shopping can be found on Fife Avenue, Sam Nujoma (Union) Avenue, Arundel Village, Avondale, Borrowdale, Eastgate and Westgate.[67] Virtually all luxury shopping is concentrated in the wealthier northern suburbs, particularly Borrowdale.

Transportation

[edit]

Harare is a relatively young city, mostly growing during the country's post-Federation and post-independence booms. It was also segregated along racial and class lines until 1976. As a result, Harare today is a mostly low-density urban area geared towards private motorists, lacking a convenient public transportation system.[68] Very little investment has been made to develop an effective and integrated public transportation system, leaving a significant number of the city's residents dependent on the city's informal minibus taxis.[68] The rise of local ridesharing apps such as GTaxi and Hwindi has partly eased pressure on the city's transportation system, but such rides are still too expensive for most working people to use.[69] In addition, bus services are also available but they are mostly geared towards intercity travel and recreation than journeys within Harare itself.

The city's public transport system includes public and private sector operations. The former consists of ZUPCO buses. Privately owned public transport included licensed station wagons (nicknamed 'emergency taxis') until 1993, when the government began to replace them with licensed buses and minibuses, referred to officially as 'commuter omnibuses'.[70] Harare has two kinds of taxis, metered taxis and the much more ubiquitous share taxis or 'kombis'. Unlike many other cities, metered taxis generally do not drive around the city looking for passengers and instead must be called and ordered to a destination. The minibus "taxis" are the de facto day-to-day form of transport relied upon by the majority of Harare's population.[71]

As of May 2023, Harare is not served by any passenger rail service. The National Railways of Zimbabwe previously operated daily overnight passenger train services to Mutare and Bulawayo using the Beira–Bulawayo railway.[72] Long-distance rail service was suspended in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and has not been restarted. Between 2001 and 2006, three commuter rail routes operated in Harare, serving Tynwald, Mufakose and Ruwa. These commuter rail routes, nicknamed 'Freedom Trains', were reintroduced in 2021, but were suspended again in November 2022 due to payment disputes with ZUPCO.[73]

Long-distance bus services link Harare to most parts of Zimbabwe.[citation needed]

The city is crossed by Transafrican Highway 9 (TAH 9), which connects it to the cities of Lusaka and Beira.

The largest airport in Zimbabwe, the Robert Gabriel Mugabe International Airport, serves Harare.

Education

[edit]The University of Zimbabwe is located in Harare. Founded in 1952, the university is the country's oldest and largest, offering a wide range of undergraduate and postgraduate programs. The student population stands at 20,399, with 17,718 undergraduate students and 2,681 postgraduate students.[74]

Sports

[edit]

Harare has long been regarded as Zimbabwe's sporting capital due to its role in developing Zimbabwean sport, the range and quality of its sporting events and venues, and its high rates of spectatorship and participation.[75] The city is also home to more professional sports teams competing at the national and international levels than any other Zimbabwean city. Football is the most popular sport in Harare, particularly among working-class residents, with the city producing many footballers who have gone on to play in the English Premier League and elsewhere.[citation needed] Cricket and rugby are also popular sports with those from middle-class backgrounds.[citation needed]

In 1995, Harare hosted most of the sixth All-Africa Games, sharing the event with other Zimbabwean cities such as Bulawayo and Chitungwiza. It hosted some of the matches of 2003 Cricket World Cup, which was hosted jointly by Kenya, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Harare also hosted the ICC Cricket 2018 World Cup Qualifier matches in March 2018.[76]

Harare is home to Harare Sports Club Ground, which hosts many Test, One Day Internationals and T20I Cricket matches. The Zimbabwe Premier Soccer League clubs of Dynamos F.C., Black Rhinos F.C., and CAPS United F.C. also call the city home.[77] Harare's main stadiums are National Sports Stadium and Rufaro Stadium.

Popular teams

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

The following table shows the major sports teams in the Harare area.

| Club | Sport | League | Founded | Venue | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamos F.C. | Association football | ZPSL | 1963[a] | Rufaro Stadium (Mbare, Harare) |

40,00 |

| CAPS United F.C. | Association football | ZPSL | 1973[a] | National Sports Stadium (Harare) |

60,000 |

| Old Georgians | Rugby Union | SSRL | 1926[a] | Harare Sports Club | 10,000 |

| Old Hararians | Rugby Union | SSRL | 1898[a] | Harare Sports Club | 10,000 |

| Black Rhinos F.C. | Association football | ZPSL | 1983 | Figaro Stadium | 17,544 |

| Mashonaland Eagles | Cricket | Logan Cup | 2009[a] | Harare Sports club | 10,000 |

| Old Miltonians | Rugby Union | SSRL | 1910[a] | Harare Sports Club | 10,000 |

Football and cricket

The main football stadiums in Harare are the National Sports Stadium and Rufaro Stadium.

Virtually all first-class and international cricket matches are hosted at Harare Sports Club, with most domestic tours occurring in spring and summer. This city is also home to the Mashonaland Eagles in the domestic Logan Cup tournament. The Eagles are coached by renowned former Zimbabwe national cricket team batsman Grant Flower.[78] The team are one of the country's strongest sides and last won the Logan Cup in the 2022-23 Logan Cup season.[79]

Rugby

Harare is also the heartland of rugby union in Zimbabwe, rivalling Windhoek in Namibia as the strongest rugby region in Africa beyond South Africa.[citation needed] The governing Rhodesia Rugby Football Union was founded in Harare in 1895 and became the Zimbabwe Rugby Union in 1980. The union and national sides are based in the northern suburb of Alexandra Park.[80] Harare is home to four of the country's national Super Six Rugby League (SSRL) clubs: Harare Sports Club, Old Georgians, Old Hararians and Old Miltonians.[81] Additionally, the Zimbabwe Rugby Academy, the national development side which plays in the second division of the Currie Cup, is largely made up of players from the city. International rugby test matches tend to be hosted at Harare Sports Club, the Police Grounds, and at Hartsfield in Bulawayo, with a particularly strong rivalry with the Namibia national rugby union team. Traditionally the city hosted tours by the British and Irish Lions, Argentina, and the All-Blacks on their respective tours of South Africa. However, this is no longer the case, due to the end of traditional rugby tours and the Zimbabwe national rugby union team's decline in the international rugby rankings.[82] Wales was the last major country to tour Harare, visiting in 1993.[83]

High school teams are generally of a high standard, with Prince Edward School, St. George's College, and St. John's College all ranking among the country's leading teams and frequently sending their first XV sides to compete against well-known South African high schools during Craven Week.[82] After high school, the city's best players unfortunately tend to move on to South Africa or the United Kingdom due to a lack of professionalism and greater educational and earning opportunities abroad, thus depleting the strength of the rugby union in Zimbabwe.[84] Notable internationals hailing from Harare include Tendai Mtawarira, Don Armand, and Brian Mujati, among numerous others.[85]

Media

[edit]Harare is host to some of Zimbabwe's leading media outlets. Despite accusations of government censorship and intimidation, the city maintains a robust press, much of which is defiantly critical of the current government.[86][additional citation(s) needed] In print media, the most internationally-famous paper is the Herald, the city's oldest newspaper, founded in 1893 and former paper of record prior to its purchase by the government. The paper is best noted for its heavy censorship during the Rhodesian Front government from 1962 to 1979, with many of its articles appearing as redacted — with black boxes marking the words removed by government censors — before its forced purchase.[87] Today it is largely seen as little more than a government mouthpiece by residents and overwhelmingly supports the government line.[88][additional citation(s) needed]

In contrast, private newspapers continue to adopt a more independent line and enjoy a diverse and vibrant readership.[citation needed] These include the Financial Gazette, the financial paper of record which is nicknamed 'the Pink Press' for its tradition of printing on a pink broadsheet. Other newspapers include: the Zimbabwe Independent, a centre-left newspaper and de facto paper of record noted for its investigative journalism; the Standard, a centre-left Sunday paper; NewsDay, a left-wing tabloid; H-Metro, a mass-market tabloid; the Daily News, a left wing opposition paper; and Kwayedza, the leading Shona language newspaper in Zimbabwe.[88][additional citation(s) needed]

Online media outlets include ZimOnline, ZimDaily, the Zimbabwe Guardian and NewZimbabwe.com amongst others.[89][90][87]

Television and radio

[edit]The state-owned ZBC TV maintains a monopoly on free-to-air TV channels in the city, with private broadcasters (such as the now-defunct Joy TV) coming and going based on the whims of the government.[91] As such, many households that can afford the cost subscribe to the satellite television distributor DStv for entertainment, news, and sport from Africa and abroad.

In November 2021, it was announced that six new free-to-air private television stations would go live in Zimbabwe and join ZBC TV after the Broadcasting Authority of Zimbabwe issued licences, ending the 64-year monopoly enjoyed by the state-owned broadcaster. Zimpapers Television Network, a subsidiary of diversified media group Zimbabwe Newspapers Ltd, was one of the channels awarded a free-to-air television licence. The other five were NRTV, 3K TV, Kumba TV, Ke Yona TV, and Channel Dzimbahwe.[92][93]

Harare is also well served by radio, with a number of the country's leading radio stations maintaining a presence in the city. There are currently four state-controlled Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation channels (SFM, Radio Zimbabwe, Power FM and National FM), as well as private national commercial free-to-air stations such as Star FM, Capital 100.4 FM, and ZiFM. In addition, Channel Zim (an alternative satellite channel) and VOA Zimbabwe both broadcast via inexpensive free-to-air decoders.[94] Eight newly licensed local commercial stations have been commissioned, but were not yet on air as of 2020.[94]

Commercial stations tend to show similar trends in programming, with high percentages of music, talk radio or phone-in programs, and sports, with only infrequent news bulletins. Despite the country's 16 official languages, virtually all broadcasts occur in English, Shona, and Ndebele.[94]

Notable institutions

[edit]Culture

[edit]

Harare has a strong cultural and artistic scene that often responds to ongoing economic and political crises, offering opportunities for satire, experimentation, and reinvention. While authors and musicians such as Doris Lessing, Petina Gappah and Thomas Mapfumo have long criticized the corruption and shortcomings of the Smith and Mugabe governments, the emergence of protest and critical theatre since 2000 has invigorated the local arts scene.[95] Actors, directors and artists have joined musicians and writers in criticizing political maleficence and audiences have rallied behind them, making the local theatre and art scene one of the most vibrant in the southern hemisphere.[96]

The city is also the site of the Harare International Festival of the Arts (HIFA), which has featured such acclaimed artists as Cape Verdean singer Sara Tavares.[97] HIFA was cancelled in 2019, and it is unclear whether it has been held in subsequent years.[98]

Harare is home to several notable museums and monuments. The National Gallery of Zimbabwe exhibits Shona art and stone sculpture. The Zimbabwe Museum of Human Sciences near Rotten Row documents the archaeology of Southern Africa through the Stone Age and into the Iron Age. Artifacts, newspapers, and other items from milestones in Zimbabwe's history can be found at the National Archives. The Heroes' Acre is a burial ground and national monument, whose purpose is to commemorate both pro-independence fighters killed during the Rhodesian Bush War and contemporary Zimbabweans who have served their country and are buried at the site.[citation needed]

Private cultural institutions include Chapungu Sculpture Park in the Msasa Park neighborhood, which displays the work of Zimbabwean stone sculptors. It was founded in 1970 by Roy Guthrie, who was instrumental in promoting the work of its sculptors worldwide.[citation needed] One notable example of architecture in Harare is the Eastgate Centre, a shopping mall with an innovative design, located equidistant from Unity Square and Borrowdale.

Green spaces

[edit]Harare has been nicknamed Zimbabwe's "Sunshine City" for its abundant parks and outdoor amenities.[43] There is an abundance of parks and gardens across town, many close to the CBD, with a variety of common and rare plant species amid landscaped vistas, pedestrian pathways, and tree-lined avenues.[43][failed verification] Harare's parks are often considered the best public parks in all of Zimbabwe's major cities.[citation needed] There are also many parks in the surrounding suburbs, particularly in the affluent suburbs of Borrowdale, Mount Pleasant, and Glen Lorne, located northeast of the central business district.[citation needed]

Within the city, prominent green spaces include:[citation needed]

- The National Botanical Gardens in Alexandra Park, which cultivates Southern African plants in woodland habitats such as the msasa, miombo, or less commonly the Cape fynbos.

- The Royal Harare Golf Course, an 18-hole championship course set in msasa woodland that hosts the Zimbabwe Open each year as part of the Sunshine Tour.

- Cleveland Dam Recreational Park, which overlooks its namesake dam and is located in msasa woodland along the highway to Mutare.

- Mukuvisi Woodlands, which comprises 263 hectares of indigenous msasa and miombo woodland and is home to zebras, giraffes, eland, wildebeest, ostriches, impalas, and birdlife and indigenous flora.[99]

Other sites near the City of Harare include Lake Chivero Dam and Recreational Park, Epworth's balancing rocks, Ewanrigg Botanical Gardens, Domboshava National Monument, Lion and Cheetah Park, and Vaughn Animal Sanctuary.[citation needed]

Places of worship

[edit]Most places of worship in Harare are Christian churches and temples.[citation needed] Some of the denominations active in Harare, and their associated places of worship, include: Assemblies of God, Baptist Convention of Zimbabwe (Baptist World Alliance), Reformed Church in Zimbabwe (World Communion of Reformed Churches), Church of the Province of Central Africa (Anglican Communion), Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Harare (Catholic Church).[100]

Sister cities

[edit]Harare has co-operation agreements, partnerships, or sister city agreements with the following towns:[101]

Cincinnati, United States[102]

Cincinnati, United States[102] Guangzhou, China[103]

Guangzhou, China[103] Kazan, Russia

Kazan, Russia Lago, Italy

Lago, Italy Maputo, Mozambique[104]

Maputo, Mozambique[104] Munich, Germany

Munich, Germany Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand

Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand Nottingham, United Kingdom

Nottingham, United Kingdom Prato, Italy

Prato, Italy Windhoek, Namibia

Windhoek, Namibia

Gallery

[edit]-

Sam Nujoma Street, looking south

-

Downtown Harare, facing the Reserve Bank

-

First Street

-

Side view of the Parliament Buildings

-

Eastgate Centre

-

Relief at National Heroes' Acre

-

National Heroes' Acre

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Zimstat. "2012 Population Census National Report" (PDF). Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Zimstat. "2012 Population Report: Harare" (PDF). Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Zimstat. "2019 Labour Force Report" (PDF). Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "Harare". Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ a b "2022 national census shows Zim rapidly urbanising". The Herald. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ Harare Provincial Profile (PDF) (Report). Parliament Research Department. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "Zimbabwe Celebrates Finish of New Parliament, Built by China". www.voanews.com. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ Abu Hassan Abu Bakar, Arman Abd Razak, Shardy Abdullah and Aidah Awang. "PROJECT MANAGEMENT SUCCESS FACTORS FOR SUSTAINABLE HOUSING: A FRAMEWORK" (PDF). School of Housing, Building and Planning, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia. Retrieved 3 March 2022 – via eprints.usm.my.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Who we are". www.who.int. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Hoste, Skipper (1977). N.S.Davies (ed.). Gold Fever. Salisbury, Rhodesia: Pioneer Head. ISBN 0-86918-013-4.

- ^ Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2013, p. 120

- ^ Horace A. Laffaye, Polo in Britain: A History, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2012, p. 76

- ^ Britannica, Harare, britannica.com, USA, accessed on 7 July 2019

- ^ Journal of Frederick Courtney Selous, Rhodesiana Reprint Library, Salisbury, 1969

- ^ Lee, M. Elaine (31 December 1975). "The origins of the Rhodesian Responsible Government Movement".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Mbiba, Beacon (2017). "Harare: from a European settler-colonial 'sunshine city' to a 'zhing-zhong' African city". International Development Planning Review. 39 (4): 375–398. doi:10.3828/idpr.2017.13. ISSN 1474-6743.

- ^ "Zimbabwe - Rhodesia, UDI, Independence | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 12 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- ^ Room, Adrian (2003). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for Over 5000 Natural Features, Countries, Capitals, Territories, Cities and Historic Sights. McFarland. ISBN 9780786418145.

- ^ "List of previous CHOGMS". Archived from the original on 31 October 2008.

- ^ "8th assembly & 50th anniversary". Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ kdc. "The Zimbabwe Situation". zimbabwesituation.com.

- ^ Sinoski, Kelly. "Vancouver world's most livable city, Harare the worst: Poll". Calgary Herald. The Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 11 June 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "Least livable cities". Reuters. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ "Zimbabwe – Rhodesia and the UDI". Encyclopedia Britannica. 3 January 2024.

- ^ "Joina City- Harare's New Pride – Inside Joina City- Facts & Figures". Urbika.com. 31 March 2010. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ "Joina City Occupancy 3pc". ForBuilder. 16 October 2011. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013.

- ^ Moyo, Jason (31 May 2013). "Zimbabwe's Changing Spaces". Mail and Guardian. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ Koranyi, Balazs (21 February 2011). "Vancouver still world's most livable city: survey". Reuters. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ The Economist Intelligence Unit (August 2012). Liveabililty Ranking and Overview August 2012 (Report). Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ Madalitso Mwando (27 March 2015). "Zimbabwe Capital Turns to Solar Streetlights to Cut Costs, Crime". allAfrica.com – Thomson Reuters Foundation. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ "Zimbabwe crowds rejoice as they demand end to Mugabe rule". BBC News.

- ^ "Zimbabwe leader Mugabe under house arrest as army tightens grip on capital". Market Watch.

- ^ a b c McGregor, JoAnn (September 2014). "Sentimentality or speculation? Diaspora investment, crisis economies and urban transformation". Geoforum. 56: 172–181. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.07.008.

- ^ Staff Writer. "A look at Zimbabwe's property market".

- ^ "Zimbabwe property market characterised by a high demand and low supply". www.iol.co.za.

- ^ a b "Why property is more pricey in Zim than SA". The Standard.

- ^ "The World According to GaWC 2020". GaWC – Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "2022 Population and Housing Census Preliminary Results". UNFPA - Zimbabwe. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ Current Africanist Research: International Bulletin. La Recherche Africaniste en Cours; Bulletin International - International African Institute. Research Information Liaison Unit - pg. 367

- ^ TV Bulpin: Discovering South Africa pp 838

- ^ https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/images/Eudasm/Africa/images/maps/download/afr_zw2006_so.jpg Provisional Soil Map of Zimbabwe Rhodesia

- ^ a b c Matamanda, Abraham R. (2020). "Mugabe's Urban Legacy: A Postcolonial Perspective on Urban Development in Harare, Zimbabwe". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 56 (4): 804–817. doi:10.1177/0021909620943620. ISSN 0021-9096. S2CID 225530172.

- ^ Page, Kogan Kogan (2003). Africa Review 200 -Op/075. Walden Publishing Limited. ISBN 9780749440657.

- ^ "Zimbabwe displays 'Biblical Ark'". 18 February 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ a b Herald, The. "Inside Rotten Row Court 6". The Herald. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "History and Architecture". The Royal Parks. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Kola, F. T. (19 November 2016). "Rotten Row by Petina Gappah review – buzzing with Zimbabwe life". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Mugabe's Borrowdale Brooke neighbour speaks out". 22 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Of suburb names and colonial hangover | Celebrating Being Zimbabwean". Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ McEwan, Peter J. M. (1963). "The European Population of Southern Rhodesia". Civilisations. 13 (4): 429–444. JSTOR 41230768.

- ^ Average for years 1965–1995, Goddard Institute of Space Studies World Climate database

- ^ Global Historic Climate Network database NGDC

- ^ https://www.goldenstairsnursery.co.zw/Golden[permanent dead link] Stairs Nursery

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Harare". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Harare Kutsaga Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Harare-Kutsaga (Salisbury) / Simbabwe" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Station Harare" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Zimbabwe". United States Department of State. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ a b Dzirutwe, MacDonald (15 May 2006). "Zimbabweans ask, who can afford houses? (Published 2006)". The New York Times.

- ^ "'Policy flip-flopping crippling real estate' - the Zimbabwe Independent". Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Engagement of the Zimbabwean Medical Diaspora" (PDF). samponline.org. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Unfriendly Neighbours" (PDF). samponline.org. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Zimbabwe's exodus to australia" (PDF). samponline.org. 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Zimbabwe: Migration and Brain Drain". ResearchGate.

- ^ Pikirayi, Innocent (2006). "The Kingdom, the Power and Forevermore: Zimbabwe Culture in Contemporary Art and Architecture". Journal of Southern African Studies. 32 (4): 755–770. doi:10.1080/03057070600995681. JSTOR 25065149. S2CID 145351878.

- ^ "Harare, capital of Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe Field Guide". zimfieldguide.com.

- ^ a b "Getting Around With Kids, When Even the Grocery Store Is an Onerous Journey". Bloomberg.com. 7 January 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Transportation in Harare, Zimbabwe". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ D.A.C. Maunder and T.C. Mbara, "The initial effects of introducing commuter omnibus services in Harare, Zimbabwe", TRL: The Future of Transport 123 (January 1995). ISBN 1-84608-122-X; and https://trl.co.uk/reports/TRL123

- ^ "A look At Public Transportation In Zimbabwe". 16 February 2020. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ Mlambo, Alois (2003). "Bulawayo, Zimbabwe". In Paul Tiyambe Zeleza; Dickson Eyoh (eds.). Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century African History. Routledge. ISBN 0415234794.

- ^ Chronicle, The. "NRZ speaks on return of intercity passenger trains". The Chronicle. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "University of Zimbabwe Profile". www.uz.ac.zw. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ "Sport in Zimbabwe". www.topendsports.com. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ "ICC World Cup Qualifiers 2018 – Super Sixes Match 8 – Zimbabwe v United Arab Emirates – Preview". Cricket World.

- ^ "'Harare among world's worst cities to live in'". DailyNews Live. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Importance of counties' Zimbabwe tours 'cannot be overstated' – Hamilton Masakadza". ESPNcricinfo.

- ^ Moyo, Brandon. "Eagles crowned Logan Cup champions". Chronicle. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ "World Rugby". www.world.rugby.

- ^ "Zim rugby league suspended". 25 April 2019.

- ^ a b Herald, The. "Rugby's forgetable year". The Herald.

- ^ "Wild times in Zimbabwe and Namibia". Welsh Rugby Union | Wales & Regions.

- ^ "Long Read | Rugby in post-colonial Zimbabwe". New Frame. 11 March 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ "'If you lived in bitterness you wouldn't enjoy anything': Exeter's Zimbabwean rugby exiles". The Guardian. 1 December 2017.

- ^ "Critics Decry Zimbabwe's Press Freedom Failures | Voice of America – English". www.voanews.com. 26 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Zimbabwe: Online News & the Internet | Columbia University Libraries". library.columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "More newspapers hit the streets of Harare as Zimbabwe media industry opens up". The National. 1 July 2010.

- ^ "Muckraker: The hunt for democracy in the land of despotism - the Zimbabwe Independent". Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ "Zimbabwe news". Stanford Libraries.

- ^ 'MuckRaker: ZBC has taken over the RBC's mantle', Zimbabwe Independent, 16 February 2012

- ^ "Major milestone as six new TV stations get licences". The Herald. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ "Zimbabwe awards new TV licences, but only to regime-linked players". The Africa Report.com. 30 November 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ a b c "Radio Stations in Zimbabwe". My Guide Zimbabwe. 24 July 2019.

- ^ "Rest in Power: Oliver Mtukudzi, music legend and pan-African trailblazer". 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Modern Sculptures from Zimbabwe". Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ "What's Next..." reflecting a sense of positive progress". hifa.co.zw. Archived from the original on 26 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Machaya, Prince (15 February 2019). "HIFA cancelled, organisers say Zimbabwe has other 'important issues'". Zimbabwe News Now. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ "Discover The Rich Zimbabwean Culture In Its Capital | Harare, Zimbabwe Activities". Lonely Planet.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Britannica, Zimbabwe – Places. britannica.com. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Dhedheya, Itai. "City of Harare – Twinning Arrangements". City of Harare. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Pennick, Faith; Calhoun, Jim (5 August 1990). "Harare newest link: Cincinnati adds sister city in Africa". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Harare twins Guangzhou". The Herald. 22 September 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Kalayil, Sheena (2 April 2015). The Beloved Country. Grosvenor House Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 9781781484647.

Bibliography

[edit]External links

[edit] Media related to Harare at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Harare at Wikimedia Commons