Basilique Saint-Urbain de Troyes

| Basilique Saint-Urbain de Troyes | |

|---|---|

West façade | |

| 48°17′53″N 4°04′36″E / 48.298128°N 4.076547°E | |

| Location | Troyes, Aube |

| Country | France |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| History | |

| Founded | 1262 |

| Founder(s) | Pope Urban IV |

| Consecrated | 1389 |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Monument historique |

| Architectural type | Basilica |

| Style | Gothic |

| Years built | 1262–1905 |

The Basilique Saint-Urbain de Troyes (Basilica of Saint Urban of Troyes), formerly the Église Saint-Urbain, is a massive medieval church in the city of Troyes, France. It was a collegial church, endowed in 1262 by Pope Urban IV. It is a classic example of late 13th century Gothic architecture. The builders encountered resistance from the nuns of the nearby abbey, who caused considerable damage during construction. Much of the building took place in the 13th century, and some of the stained glass dates to that period, but completion of the church was delayed for many years due to war or lack of funding. Statuary includes excellent examples of the 16th century Troyes school. The vaulted roof and the west facade were only completed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It has been listed since 1840 as a monument historique by the French Ministry of Culture.[1]

Origins

[edit]Jacques Pantaléon (c. 1195–1264) was the son of a shoemaker in Troyes. He studied at the Cathedral school for a short period, then moved to Paris to study theology at the Sorbonne. He rose through the church hierarchy and was appointed Patriarch of Jerusalem in 1255. He was elected pope in 1261 and chose the name of Pope Urban IV.[2] In May 1262 he announced that he would build a cathedral in Troyes dedicated to Saint Urban, his patron saint.[3] For the church site, Urban IV purchased several houses around the building that had housed his father's workshop.[4] The property had belonged to the Abbey of Notre Dame aux Nonnains.[3]

Structure

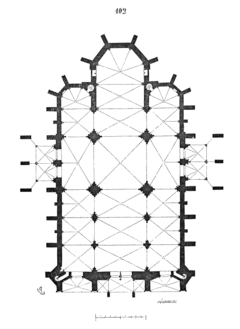

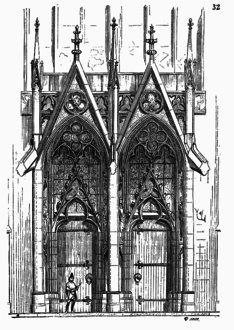

[edit]Saint-Urbain is a classic example of French Gothic architecture of this period.[5] The exterior has perforated gables with sharp points, narrow buttresses with many pinnacles, and openwork flying buttresses. The effect is visually complex, perhaps discordant. The main structural elements are built from a resistant limestone from Tonnerre, while softer local chalk is used for infilling masonry of the walls.[6] The interior floor plan is compact. There is a short nave with three bays, a transept that does not project from the side walls and a stubby chevet that ends in three polygonal apses. There is no ambulatory.[7] The building makes spectacular use of tracery and attenuated forms.[7]

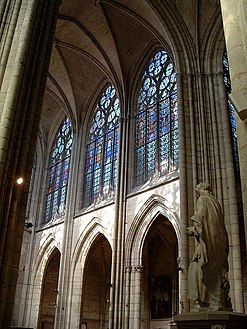

The interior walls have two different patterns. The apse has two levels of glass windows, which create a luminous area around the altar, above a plain masonry base. There is a walkway on the lower level behind an open tracery screen whose mullions rise to the clerestory above. The sanctuary, transept and nave have a strongly built arcade at the lower level supported by composite piers, above which rises a clerestory of similar height. The two patterns are unified by the framework of rectilinear wall sections and the grid of vertical and horizontal elements.[6]

The building does not aim for monumental effect, as with earlier Gothic buildings, but instead has been called a "delicate glass cage". The architect eliminated the triforium, simplified the plan and concentrated on refining detail.[8] The streamlined design was copied in later Gothic churches.[7] The architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814–79), who led the Gothic revival of the 19th century, considered that Saint-Urbain represented the finest example of the system of construction in which the columns that support the vault extend continuously into the arches of the vault, without the massive Romanesque capitals of earlier periods.[9] Saint-Urbain has been called the "Parthenon of Champagne".[2]

-

Floor plan

-

Stained glass of the choir

-

Nave

-

Porches

Decor

[edit]Stained glass windows

[edit]The sober, elegant interior of the church is filled with light from the huge windows.[4] The original church glazing followed the new band window style, with colored compositions in large rectangular fields surrounded by bright grisaille glass.[10] This system is used for narrative depictions in both the upper and lower levels.[11] Viollet le Duc dated the stained glass in the church to around 1295, but the ornament in its borders and grisaille is from an earlier tradition. It has a cross-hatched ground, as in Merton College, Oxford, but has a very simple leaded pattern and includes much natural foliage.[12] The windows of the choir, and others in the church, date to the original glazing of 1264–66. They were badly damaged during the fire of 1266, but still show two rows of full color figures. Jane Hayward considers that the windows "exhibit the reuse of surviving figures by two masters, one preferring elongated figures in broad-fold drapery ... and the other more archaic and regional (with leaded-in eyes)." For some reason the windows did not depict either Saint Cecilia or Saint Urban, although tapestries to these saints were meant to be hung in the choir.[13] The original windows were restored in 1992 by Le Vitrail of Troyes.[2] The other windows date to the late 19th or early 20th centuries.[4]

Sculpture

[edit]

The piscine of Saint-Urbain, which dates to 1265, is unusually large. This is a carved stone recess in the choir where the ampoules containing holy oils are placed, pierced with holes through which waters used in purification ceremonies are poured.[14] The Saint-Urbain piscine is accessed through two high windows above which are trefoil decorations of three scenes: Jesus blessing the Virgin in the centre, Urban IV presenting the church choir to the left and Cardinal Ancher presenting the transept to the right. Above these decorations, which were damaged during the French Revolution, is a carved representation of armed soldiers, clergymen and workers struggling to defend the walls of a medieval town against enemies.[14] There is a magnificent 13th-century Last Judgement on the pediment.[2]

The Champagne fairs made Troyes a prosperous city before the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453). With the return of peace in the mid-15th century the city recovered, and its workshops making sculpture, paintings and stained glass flourished. The sculptural style from before the wars was revived, with the Gothic tradition of clean lines, simple facial expression and sober garments.[14] Starting in the 1530s the influence of artists from the Château de Fontainebleau began to spread in the region. The style evolved under the influence of the Renaissance, with more elaborate hair styles, more natural poses and richer clothing.[14] The statue of the Vierge aux Raisins in the chapel on the south aisle is an excellent example of the Troyes school of the 16th century.[2] However, some of the studios in Troyes, such as those of the Maitre de Chaource, resisted these innovations and continued to create works of great quality in the pure Gothic tradition.[14]

Tapestry

[edit]Pierre Desrey (c. 1450–1514) gave instructions for the design of tapestries that would depict the legends of Saint Urban and Saint Cecilia for the church, but left much discretion to the artist.[15] The tapestries were apparently never woven.[13] In 1783 J. C. Courtalon-Delaistre wrote of the church, "Old tapestries representing the life of Urban IV surround the choir. Here you see his father working at the craft of shoemaker and his mother winding her distaff. They were made in 1525, at the expense of the canon Claude de Lirey called Boullanger".[16]

History

[edit]Construction

[edit]The pope gave the architect Jean Langlois a huge amount of money to undertake the work.[2] Construction probably began in 1263. Although Pope Urban IV died the next year his nephew, Cardinal Ancher, supervised the continued construction.[3] The church was built from east to west.[7] The choir and transept were erected quickly between 1264 and 1266.[4] The main altar was dedicated in October 1265. Visitors to the church on 25 May 1266, the saint's feast day, were granted an indulgence of one year and forty days.[3]

The Abbey of Notre Dame aux Nonnains had great power and privileges in Troyes. A collegiate church that would be outside its jurisdiction and directly under the Holy See was a serious threat. In 1266, when the date on which Saint-Urbain would be consecrated had already been decided, the abbess Ode de Pougy sent a gang to the site that destroyed as much as possible. The doors were broken off, the high altar and capitals broken, the columns vandalized and the carpenters' tools and material confiscated. New doors were installed, which were also broken and removed soon after. A few months later a fire broke out that destroyed the wooden parts of the walls and the roof.[14]

After the fire a new architect continued the work, but was short of funds. In 1268 the nuns hired armed men who prevented the Archbishop of Tyre and the Bishop of Auxerre from blessing the new cemetery.[13] On 15 July 1268 Pope Clement IV excommunicated Ode de Pougy and her associates.[14][a] Construction continued despite the opposition of the nuns and the lack of money.[13] The envelope wall and the easternmost bay of the nave were added before work stopped at the end of the 13th century. Work resumed in the late 14th century, when two more bays were added to the nave, and a simple wooden shell was added to serve as a vault over the unfinished portion.[4] The church was consecrated on 1 July 1389 while still unfinished.[13] The main section of the church was not finished until the 16th century, and the tower was not completed until 1630.[17]

Decay

[edit]No more work was done for many years, and the structure deteriorated. Fourteen houses were built against the church walls. During the French Revolution the church was used as a granary and then as a store for distribution of supplies. In 1802 the building again became a parish church.[4] The baptismal font comes from the Saint-Jacques-aux-Nonnains church. All the furniture of this church was sold during the Revolution. A few years later the font was found in the courtyard of a house in Troyes, where it was being used as a curbstone for a well.[14]

Restoration

[edit]A project to fully restore the building was initiated in 1846. The abutting houses were removed.[4] The architect Paul Selmersheim (1840–1916) finished the upper part of the nave at the end of the 19th century according to the original plan.[2] In the late 20th century the apse and its windows were completely restored. Between 1890 and 1905 the upper vault and buttresses of the nave were completed and the porch of the facade was added.[4] The portal which covers the west side of the church was completed in 1905.[2]

Urbain IV had been buried in the Perugia Cathedral in 1264, although he had wanted to be buried in the church at Troyes. His remains were transferred to the church in 1935.[2] Pope Paul VI elevated the church to the rank of a minor basilica in 1964.[4]

A one-year study of air pollution inside the church in 2002–03 showed that CO2 spikes occur during Sunday masses, when large volumes of outside air are admitted, while Elemental Carbon (EC) pollution is primarily caused by candle burning. The effect on the stained glass is not yet understood.[18]

-

Church from the west in the 19th century

-

Church from the south in the 19th century

-

From the southeast in 2014

-

Interior towards choir

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pope Martin IV lifted the excommunication of Ode de Pougy in 1283.[14]

- ^ Base Mérimée: PA00078261, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French) Eglise Saint-Urbain

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Basilique Saint-Urbain ... Office de Tourisme.

- ^ a b c d Kane 2010, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Troyes, basilique Saint-Urbain.

- ^ Basilique Saint-Urbain ... Visiter la Champagne.

- ^ a b Hourihane 2012, p. 172.

- ^ a b c d Murray, Tallon & O'Neill.

- ^ Janson & Janson 2003, PT337.

- ^ Léniaud 1994.

- ^ Hourihane 2012, p. 121.

- ^ Hourihane 2012, p. 194.

- ^ Westlake 1882, p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e Kane 2010, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rivière 2001.

- ^ Pastan, White & Gilbert 2014, p. 15.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 56.

- ^ Simpson 1997, p. 16.

- ^ Saiz-Jimenez 2004, p. 26.

Sources

[edit]- "Basilique Saint-Urbain (13th C)". Office de Tourisme de Troyes. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- "Basilique Saint-Urbain de Troyes - Sites Religieux". Visiter la Champagne (in French). Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-15.

- Hourihane, Colum (2012-12-06), The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture, OUP USA, ISBN 978-0-19-539536-5, retrieved 2015-12-16

- Janson, Horst Woldemar; Janson, Anthony F. (2003), History of Art: The Western Tradition, Prentice Hall Professional, ISBN 978-0-13-182895-7, retrieved 2015-12-16

- Kane, Tina (2010), The Troyes Memoire: The Making of a Medieval Tapestry, Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 978-1-84383-570-7, retrieved 2015-12-16

- Léniaud, Jean-Michel (1994), Viollet-le-Duc ou les délires du système, Beaux Livres (in French), Éditions Mengès, p. 225, ISBN 2-8562-0340-X

- Murray, Stephen; Tallon, Andrew; O'Neill, Rory, "Troyes, Église Saint-Urbai", Mapping Gothic France, Media Center for Art History, Columbia University; Art Department, Vassar College, archived from the original on 2015-09-28, retrieved 2015-12-16

- Pastan, Elizabeth Carson; White, Stephen D.; Gilbert, Kate (2014), The Bayeux Tapestry and Its Contexts: A Reassessment, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, ISBN 978-1-84383-941-5, retrieved 2015-12-16

- Rivière, Rémi (2001), Basilique Saint-Urbain, Troyes : Guide de visite (in French), Roy, Dominique, photography, p. 64, ISBN 2-907894-26-9

- Saiz-Jimenez, C. (2004-08-15), Air Pollution and Cultural Heritage, CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-4822-8399-0, retrieved 2015-12-16

- Simpson, Patricia (1997), Marguerite Bourgeoys and Montreal, 1640-1665, McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, ISBN 978-0-7735-1641-0, retrieved 2015-12-16

- "Troyes, basilique Saint-Urbain", Patrimoine-histoire (in French), retrieved 2015-12-16

- Westlake, Nat Hubert John (1882), A History of Design in Painted Glass, J. Parker and Company, retrieved 2015-12-16

External links

[edit] Media related to Basilique Saint-Urbain de Troyes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Basilique Saint-Urbain de Troyes at Wikimedia Commons