USS Jimmy Carter

Jimmy Carter returns to NSB Kitsap, 2017

| |

Jimmy Carter's profile

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | USS Jimmy Carter |

| Namesake | Jimmy Carter |

| Ordered | 29 June 1996 |

| Builder | General Dynamics Electric Boat |

| Laid down | 5 December 1998 |

| Launched | 13 May 2004 |

| Christened | 5 June 2004 |

| Commissioned | 19 February 2005 |

| Homeport | Bangor Annex of Naval Base Kitsap, Washington |

| Motto | Semper Optima ("Always the Best") |

| Status | in active service |

| Badge |  |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Modified Seawolf-class submarine |

| Displacement | |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 12.1 m (39.7 ft) |

| Draft | 10.9 m (35.8 ft) |

| Propulsion | |

| Speed | greater than 25 knots (46 km/h)[4] |

| Complement | 15 officers, 126 enlisted |

| Armament | 8 × 26.5 inch torpedo tubes, sleeved for 21 inch weapons[5] (up to 50 Tomahawk land attack missile/Harpoon anti-ship missile/Mk 48 guided torpedo carried in torpedo room)[6] |

USS Jimmy Carter (SSN-23) is the third and final Seawolf-class nuclear-powered fast-attack submarine in the United States Navy. Commissioned in 2005, she is named for the 39th president of the United States, Jimmy Carter, the only president to have qualified on submarines.[7] The only submarine to have been named for a living president, Jimmy Carter is also one of the few vessels, and only the third submarine of the US Navy, to have been named for a living person. Extensively modified from the original design of her class, she is sometimes described as a subclass unto herself.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Construction

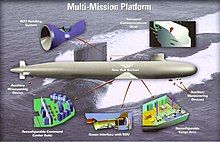

[edit]The contract to build Jimmy Carter was to the Electric Boat Division of General Dynamics Corporation in Groton, Connecticut on 29 June 1996, and her keel was laid on 5 December 1998. Original schedules called for Jimmy Carter to be commissioned in late 2001 or early 2002. Electric Boat was awarded an $887 million extension to the Jimmy Carter contract on 10 December 1999 to modify the boat for testing new submarine systems and classified missions previously carried out by USS Parche.[8] During modification, her hull was extended 100 feet (30 m) to create a 2,500-ton supplementary middle section which forms a Multi-Mission Platform (MMP). This section is fitted with an ocean interface for divers, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), and special operation equipment; ROV handling system, storage, and deployment space for mission systems, and a pressure-resistant passage between the fore and aft parts of the submarine to accommodate the boat's crew.[9][10][11]

Jimmy Carter was christened on 5 June 2004, and the ship sponsor was former First Lady Rosalynn Carter. One result of the changes was that Jimmy Carter was commissioned more than six years after USS Connecticut and almost four months after the commissioning of USS Virginia, the first of the Virginia-class subs.

Jimmy Carter has additional maneuvering devices fitted fore and aft that allow her to keep station over selected targets in odd currents. Intelligence experts speculate that the MMP may find use in missions as an underwater splicing chamber for optical fiber cables.[12][13][14][15]

Deployments

[edit]On 19 November 2004 Jimmy Carter completed alpha sea trials, her first voyage in the open seas. On 22 December, Electric Boat delivered Jimmy Carter to the US Navy, and she was commissioned 19 February 2005 at NSB New London.

Jimmy Carter began a transit from NSB New London to her new homeport at the Bangor Annex of Naval Base Kitsap, Washington on 14 October 2005 but was forced to return when an unusually high wave caused damage while the submarine was running on the surface. The damage was repaired and Jimmy Carter left New London the following day, arriving at Bangor the afternoon of 9 November 2005.

In April and September 2017 Jimmy Carter returned twice to her homeport at Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor, flying a Jolly Roger flag, traditionally indicative of a successful mission.[16]

Awards

[edit]- 2007 Battle Efficiency Award, commonly known as a "Battle E".[17]

- 2012 Battle Efficiency Award.[citation needed]

- 2013 Presidential Unit Citation, the equivalent to the Navy Cross for the entire ship, for what has been reported as "Mission 7."[18][19]

Gallery

[edit]-

Jimmy Carter during the submarine's commissioning ceremony, 19 February 2005

-

Departing NSB Kings Bay with Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter aboard, 2005

-

Former President Carter holding a model of the boat that carries his name.

-

Jimmy Carter in the Magnetic Silencing Facility at Naval Base Kitsap for her first deperming treatment.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Alan Kuperman; Frank von Hippel (10 April 2020). "US study of reactor and fuel types to enable naval reactors to shift from HEU fuel". IPFM Blog.

- ^ a b "Validation of the Use of Low Enriched Uranium as a Replacement for Highly Enriched Uranium in US Submarine Reactors" (PDF). dspace.mit.edu. June 2015. p. 32. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "S6W Advanced Fleet Reactor". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Schank, John F.; Cesse, Cameron; Ip, Frank W.; Lacroix, Robert; Murphy, Mark V.; Arena, Kristy N.; Kamarck; Lee, Gordon T. (2011). "Learning from Experience: Volume II: Lessons from the U.S. Navy's Ohio, Seawolf, and Virginia Submarine Programs". rand.org.

- ^ "Attack Submarines - SSN". United States Navy Fact Files. United States Navy. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "Lieutenant James Earle Carter, Jr., USN". Naval History & Heritage Command. United States Navy. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Zimmerman, W. Frederick (2008). SSN-23 Jimmy Carter: U.S. Navy Submarine (Seawolf Class). Nimble Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-934840-30-6.

- ^ RADM Davis, J. P. USS JIMMY CARTER (SSN23): Expanding Future SSN Missions, Undersea Warfare, Fall 1999, pp. 16-18.

- ^ PCU Jimmy Carter Christened at Electric Boat Archived 17 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Navy, Story Number: NNS040609-07, Release Date: 6/9/2004

- ^ The Navy's underwater eavesdropper, Reuters, 19 July 2013

- ^ "New Nuclear Sub Is Said to Have Special Eavesdropping Ability". The New York Times. Associated Press. 20 February 2005. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ^ Zorpette, Glenn (January 2002). "Making Intelligence Smarter". IEEE Spectrum. 39 (1). IEEE: 38–43. doi:10.1109/6.975021. ISSN 0018-9235.

- ^ Neil Jr. (23 May 2001). "Spy agency taps into undersea cable". ZDNet News. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ^ "Jimmy Carter: Super Spy?". Defensetech.org. 21 February 2005. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ^ Wetzel, Gary (17 September 2017). "America's Most Secret Spy Sub Returned To Base Flying A Pirate Flag". Gizmodo.

- ^ Rowley, Eric (22 January 2008). "Pacific Northwest Sub Crews Win Battle "E"". Navy.mil. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ^ "This secretive U.S. Navy submarine went on a dangerous mission". theweek.com. 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ "The mystery of the USS Jimmy Carter and Mission 7". tnationalintrest.org. 11 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

External links

[edit]- Naval Vessel Register entry for USS Jimmy Carter

- Navy Commissions USS Jimmy Carter Archived 5 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, from the Navy's Commander Submarine Group Two website

- USS Jimmy Carter: Expanding Future SSN Missions

- oralhistoryproject.com: World War II Submarine Veterans History Project

- NavSource Online: USS Jimmy Carter (SSN-23)

- USS Jimmy Carter Multi-Mission Platform, in PDF format

- James Bamford Inside the National Security Agency (Lecture) American Civil Liberties Union KUOW-FM PRX NPR 24 February 2007 (53: minutes)

- Big Brother Is Listening by James Bamford The Atlantic April 2006