Rollo Beck

Rollo Howard Beck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 26, 1870 |

| Died | November 22, 1950 (aged 80) |

| Education | 8th grade |

| Known for | Catalog of Regional Biodiversity |

| Spouse | Ida Menzies |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Ornithology |

| Institutions | University of California, Berkeley |

| Patrons | Lionel Walter Rothschild, Leonard C. Sanford, Harry Payne Whitney |

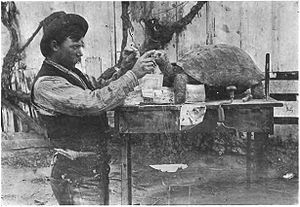

Rollo Howard Beck (26 August 1870 – 22 November 1950) was an American ornithologist, bird collector for museums, and explorer.[2][3] Beck's petrel and three taxa of reptiles are named after him, including a subspecies of Galápagos tortoise, Chelonoidis nigra becki from Volcán Wolf. A paper by Fellers examines all the known taxa named for Beck.[4] Beck was recognized for his extraordinary ability as a field worker by Robert Cushman Murphy as being "in a class by himself,"[5] and by University of California at Berkeley professor of zoology Frank Pitelka as "the field worker" of his generation.[6]

Early years

[edit]Rollo Howard Beck was born in Los Gatos, California, and grew up in Berryessa working on apricot and prune orchards. He completed only an 8th grade education, but took an early interest in natural history, trapping gophers after school on neighborhood farms. One of his neighbors, Frank H. Holmes, was a good friend of the ornithologist Theodore Sherman Palmer. Palmer also introduced Beck to Charles Keeler, who studied birdlife of the San Francisco Bay Area, and Beck learned about upland birds hunting quail with Holmes. Beck's interest and knowledge of birds grew, and he soon learned how to make ornithological specimens and mount birds for museum collections. He joined the American Ornithologists' Union in 1894, and was among the first members of the newly formed Cooper Ornithological Society which formed in San Jose, California. He participated in early ornithological expeditions to the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Yosemite, and Lake Tahoe with Holmes and Wilfred Hudson Osgood, and collected and helped describe the first eggs and nests of the western evening grosbeak and hermit warbler.[7]

Expeditions

[edit]

Channel Islands of California

[edit]In the spring of 1897, Beck headed south to Santa Barbara, California, where he learned to sail a moderate-sized schooner under captain Sam Burtis. He visited the Channel Islands of, including Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel islands collecting and documenting birds as well as nests and eggs. Beck was the first to collect and document the differences of the island scrub-jays that live on the Channel Islands, now recognized as distinct from mainland forms.[8]

Galápagos Islands, Ecuador

[edit]Later in 1897, while on his way back to the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Beck was invited to join an ornithological expedition to the Galápagos Islands off the coast of Ecuador, organized by Frank Blake Webster[9] and funded by Lionel Walter Rothschild, of Tring, England, later, and only after his father's death in 1915, Lord Rothschild. The expedition was launched to study and collect giant tortoises and the land birds of the Galápagos, and here Beck also polished his sailing skills and became better acquainted with seabirds and the unique fauna of the Galápagos. Beck returned again to the Galápagos to collect more specimens around 1901, and he personally delivered these specimens to Walter Rothschild in Tring. While in Tring, he planned future potential collecting trips to Colombia for Rothschild, and he returned to California by way of Washington, DC, in order to apply for the necessary permits.

Cocos and Galápagos

[edit]Back in San Francisco, Beck met with Leverett Mills Loomis, Director of the California Academy of Sciences.[10] Loomis was interested in seabirds, especially the Tubinares, now the Procellariiformes, and hired Beck to collect in Monterey Bay, the Channel Islands of California, and the Revillagigedo Islands of Mexico, while he waited for his Colombia permits. In 1905–1906, Beck was hired by the California Academy of Sciences to organize and lead a large seagoing expedition to Cocos Island and the Galápagos Islands aboard the Schooner “Academy.”[11] Loomis organized scientific specialists in botany, herpetology, entomology, and malacology, geology, paleontology, as well as ornithology. Besides Beck, the expedition's scientists were: Alban Stewart, botanist;[12][13][14] W. H. Ochsner, geologist/paleontologist/malacologist; F. X. Williams, entomologist/malacologist; E. W. Gifford and J. S. Hunter, ornithologists; J. R. Slevin and E. S. King, herpetologists.[15][16] Together they assembled the largest scientific collection of specimens from the archipelago ever, leading to our great understanding of the biota of the islands.

The great April 18, 1906 San Francisco earthquake and three days of subsequent fire struck while Beck and the expedition were still in the Galápagos Islands. They would not return to San Francisco until Thanksgiving Day, November 29, 1906. Their extensive collections of some 78,000 specimens allowed the academy as an institution to rise, literally and figuratively, from the ashes of "the great conflagration" that devastated San Francisco.[17] The schooner “Academy” acted as the meeting place and storage place for the California Academy of Sciences for several months after their return. Some historians believe that had Beck and the expedition not been out to sea and collecting, the academy would have suffered a lethal blow.[18]

Beck married his wife and lifelong companion, Ida Menzies of Berryessa, in 1907 in Honolulu, Hawaii. He went to work for Joseph Grinnell, the Director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, in the spring of 1908, and collected waterbirds for Grinnell's studies of California birds. Before long, Beck was offered even more money by Dr. Leonard C. Sanford, of New Haven, Connecticut, to collect birds in Alaska for the well-known ornithologist Arthur Cleveland Bent, who was collecting for his studies of “The Life Histories of North American Birds.” He did much of the field work with the young Alexander Wetmore, who had recently graduated from college.

Brewster-Sanford Expedition to South America

[edit]In 1912, Dr. Leonard Cutler Sanford proposed a larger two-year expedition (that ended up taking five years) to South America for Rollo and Ida, and financed by Mr. F. F. Brewster. They traveled up into lakes and highlands of the Andes, along the coast, and out at sea to the Falkland Islands and Juan Fernández Islands, sailed around Cape Horn in a 12-ton cutter, and up into the Caribbean. This work and these collections proved invaluable to Robert Cushman Murphy, who later published “The Oceanic Birds of South America”[19] based in part on the Brewster-Sanford Expedition collection of Rollo Beck.

Whitney South Sea Expedition

[edit]In 1920 Beck was contacted by Dr. Sanford who proposed an extended South Pacific expedition. The fieldwork was funded by Harry Payne Whitney of New York, and the specimens were bound for the American Museum of Natural History. This became the longest and greatest of all Beck's expeditions and, as with the "Academy" expedition of 1905–06, he was joined by many other accomplished biologists and field collectors with complementary skills, including E. H. Quayle, J. G. Correia, Dr F. P. Drowne, Hannibal Hamlin, Guy Richards, Ernst Mayr, E. H. Bryan Jr., and others. Beck left the expedition in 1929, after sailing through the Pacific, from Tahiti to New Guinea to New Zealand and visiting hundreds of islands between. Rollo and Ida Beck returned to the California in 1929 with over 40,000 bird skins and a large anthropological collection. This expedition remains to this day the most comprehensive survey and study of birds in the south-west Pacific islands, and has been written up in dozens of important scientific monographs of birds. The specimens residing at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City form the most comprehensive collection of Pacific birds anywhere.

Rollo and Ida Beck retired to the northern California town of Planada, near Merced, where they continued to study natural history and provide specimens of great scientific value. Most of these later specimens are housed at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, and at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California, Berkeley. There is also a substantial collection at San Jose State University. There is a smaller collection of mounted specimens on exhibit at the Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History, in the town of Pacific Grove, California, as well as a permanent exhibit devoted to the life and work of Rollo Beck.

Contributions to science

[edit]The work of Beck and other early ornithologists was undertaken primarily to document biodiversity before it was lost forever[20] without being recorded, and to understand the evolution and ecology of organisms from the regions visited during the expeditions.[21] The work of Beck and others brought an awareness of and a catalog of regional biodiversity that is essential to have in order to do modern conservation. Much of what we know about western U.S. birds and Pacific ornithology – from Bent's "Life Histories of North American Birds"[22] to Murphy's "Oceanic Birds of South America"[23] - rests on the fieldwork of Rollo Beck and other early ornithologists. Some believe that our understanding of global biodiversity and the practice of modern conservation biology, much of which seems to be anti-collecting, owes much to these early collectors who worked so diligently to document and preserve voucher specimens in museums.

Collection methods

[edit]Human history is replete with examples of island species that were being persecuted by farmers, ranchers, hunters, and sailors; were being harvested unsustainably; and were being decimated by introduced species.[24] By comparison, scientific collectors were relatively few in number and seldom took large numbers of specimens of any one species, but competition between museums and private collectors to acquire the rarest of the rare put disproportionate collecting pressure on species whose populations were already teetering on the brink for other reasons. Beck and others in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were responding to published statements that "time was running out" and that species should be collected and documented in museum collections "before it is too late." In the absence of a conservation framework and infrastructure, Beck and others engaged in what can be called "salvage collecting," which hastened the extinctions and which does not correspond to modern conservation thinking.

Rollo Beck has been blamed for having collected a sample of Guadalupe caracaras in 1900 which were being exterminated by goat herders who viewed the bird as a predator.[25] At the time he assumed the birds were common on Guadalupe Island, but in retrospect he wrote that those he collected might have been the last.[26] Beck also collected, as museum specimens, three of the last four individuals of the subspecies of Galápagos tortoise Geochelone nigra abingdonii, the Pinta Island tortoise. The last individual of that island's tortoise population became known as Lonesome George when it was found on Pinta Island in November 1971.

Reptiles named in honor of Beck

[edit]Rollo Beck is commemorated in the scientific names of three taxa of reptiles.[27]

- Chelonoidis nigra becki, a tortoise

- Sceloporus becki, a lizard

- Sphaerodactylus becki, a lizard

References

[edit]- ^ American Museum of Natural history http://data.library.amnh.org/archives-authorities/id/amnhp_1000142

- ^ Pitelka, Frank A. 1986. Rollo Beck - Old-school collector, member of an endangered species. American Birds 40(3): 385-387.

- ^ Dumbacher, John P. and West, Barbara. 2010. Collecting Galápagos and the Pacific: How Rollo Beck shaped our understanding of evolution. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, 4th Series, Vol. 61, Suppl. II, No. 13, pp. 211-243. http://research.calacademy.org/sites/research.calacademy.org/files/Departments/Darwin%20PCAS%20v61%28Sept%2910%20Suppl%20II%20Dumbacher%26WestLR.pdf Archived December 5, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fellers, Gary M. 2014. Animal taxa named for Rollo H. Beck. Archives of Natural History 41(1): 113-123.

- ^ "v.1 - Oceanic birds of South America : - Biodiversity Heritage Library". Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ Pitelka, Frank A. 1986. Rollo Beck - Old-school collector, member of an endangered species. American Birds 40(3): 385-387.

- ^ s:The Condor/1 (5)/Rollo H. Beck

- ^ s:The Condor/1 (1)/Nesting of the Santa Cruz Jay

- ^ Barrow, Jr., Mark V. 2000. The specimen dealer: Entrepreneurial natural history in America's Gilded Age. Journal of the History of Biology 33: 493-534.

- ^ Dumbacher, John P.; West, Barbara (January 2010). "Collecting Galápagos and the Pacific: How Rollo Howard Beck Shaped Our Understanding of Evolution". Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. 61 (2): 211–243.

- ^ Worman, John. "Ships List". Galápagos History & Cartography.

- ^ Stewart, Alban (January 19, 1912). "Notes on the botany of Cocos Island". Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. 1: 375–404.

- ^ Stewart, Alban (January 20, 1911). "A Botanical survey of the Galapagos Islands". Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galapagos Islands, 1905-1906 ;2. 1. California Academy of Sciences: 7–288.

- ^ Morris, E. L. (October 18, 1911). "Review of Stewart's Botanical Survey of the Galapagos Islands". Torreya. 11: 220–221.

- ^ Expedition of the California Academy Sciences to the Galápagos Islands. San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences. 1912. p. 2.

- ^ Wolff, Matthias; Gardener, Mark, eds. (2012). "Chapter 5 (Subheading: Eight young men) by Matthew J. James". The Role of Science for Conservation. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 9781136458446.

- ^ James, Matthew J. 2012. The boat, the bay and the museum: Significance of the 1905-1906 Galápagos expedition of the California Academy of Sciences. In: The Role of Science for Conservation, edited by M. Wolff and M. Gardener, pp. 87-99. London: Routledge, xviii + 299 pp. http://sonoma.edu/geology/docs/JAMES_BoatBayMuseum.pdf

- ^ James, Matthew J. 2010. Collecting Evolution: Vindication of Charles Darwin by the 1905-1906 Galapagos Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, 4th Series, Vol. 61, Suppl. II, No. 12, pp. 197-210. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 20, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Murphy, Robert Cushman. (1936). The Oceanic Birds of South America. American Museum of Natural History. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/45089#page/1/mode/1up https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/44597#page/9/mode/1up

- ^ Chapman, Frank M. (1935). "The Whitney South Seas Expedition". Science. 81 (2091): 95–7. Bibcode:1935Sci....81...95C. doi:10.1126/science.81.2091.95. PMID 17816636. S2CID 35137435.

- ^ See also: Dumbacher, J.P. and West, B. 2010.

- ^ Life Histories of North American Birds https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/59509#page/7/mode/1up

- ^ Oceanic Birds of South America https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/45089#page/10/mode/1up

- ^ Quammen, David. (1997). The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinction. New York: Simon & Schuster ISBN 0684827123.

- ^ Bousman, William G. (2005). Local Ornithology in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries. Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society.

- ^ Abbott, C. B. (1933). "Closing history of the Guadalupe Caracara" (PDF). Condor. 35 (1): 10–14. doi:10.2307/1363459. JSTOR 1363459.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Beck", p. 21).

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Rollo Beck at the Internet Archive

- The Pacific Voyages of Rollo Beck

- Rollo Beck biography

- Rollo Beck online exhibit of the Pacific Grove Museum Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Web link invalid March 18, 2014; still invalid September 9, 2016.