Ring finger

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

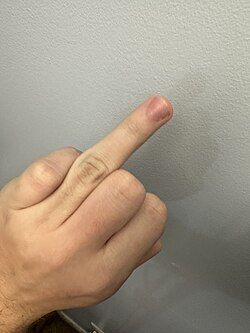

| Ring finger | |

|---|---|

A left human hand with the ring finger extended | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Proper palmar digital arteries, dorsal digital arteries |

| Vein | Palmar digital veins, dorsal digital veins |

| Nerve | Dorsal digital nerves of radial nerve, Dorsal digital nerves of ulnar nerve, Proper palmar digital nerves of median nerve |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | digitus IV manus, digitus quartus manus, digitus annularis manus, digitus medicinalis |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.056 |

| TA2 | 154 |

| FMA | 24948 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The ring finger, third finger,[1] fourth finger,[2][3] leech finger,[4] or annulary is the fourth digit of the human hand, located between the middle finger and the little finger.[5]

Sometimes the term ring finger only refers to the fourth digit of a left-hand, so named for its traditional association with wedding rings in many societies, although not all use this digit as the ring finger. Traditionally, a wedding ring was worn only by the bride or wife, but in recent times more men also wear a wedding ring. It is also the custom in some societies to wear an engagement ring on the ring finger.

In anatomy, the ring finger is called digitus medicinalis, the fourth digit, digitus annularis, digitus quartus, or digitus IV. In Latin, the word anulus means "ring", digitus means "digit", and quartus means "fourth".

Etymology

[edit]The origin of the selection of the fourth digit as the ring finger is not definitively known. According to László A. Magyar, the names of the ring finger in many languages reflect an ancient belief that it is a magical finger. It is named after magic or rings, or called nameless (for example, in Chinese: 無名指 / 无名指; pinyin: wúmíng zhǐ; lit. 'unnamed finger').[6]

In Hungarian, it is called nevetlen ujj; lit. ‘nameless finger’ or nevezetlen ujj; lit. ‘unnamed finger’. It has special role in magical practices like healing, protection against curse or love magic. For example to heal a stingy eye or a pimple or a ringworm one must draw a cross on it with the nameless finger or rub it gently. If a woman wants to make a man to love her, she should sting her unnamed finger and drop her blood to the mans drink (wine). If the man drinks that he will has a strong bond for that woman, he will love her.[7]

In Japanese, it is called 薬指 (kusuri yubi, lit. 'medicine finger'), deriving its name from the fact that it was frequently used when taking traditional powdered medicine, as it was rarely used otherwise and hence was considered the cleanest of all.[8]

In other languages such as Sanskrit, Finnish, and Russian, the ring finger is called "Anamika", "nimetön", and "Безымянный" (bezymianny, "nameless"), respectively.

In Semitic languages such as Arabic and Hebrew, the ring finger is called bansur (meaning "victory") and kmitsa (meaning "taking a handful"), respectively.

History

[edit]Before medical science discovered how the circulatory system functioned, people believed that a vein ran directly from the fourth digit on the left hand to the heart.[9] Because of the hand–heart connection, they chose the descriptive name vena amoris, Latin for the vein of love, for this particular vein.[10]

Based upon this name, their contemporaries, purported experts in the field of matrimonial etiquette, wrote that it would only be fitting that the wedding ring be worn on this digit. By wearing the ring on the fourth digit of the left hand, a married couple symbolically declares their eternal love for each other.[11]

In Britain, only women tended to wear a wedding ring until after the World Wars, when married male soldiers started to wear rings to remind them of their wife.[12]

Contemporary customs

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Western customs

[edit]In Western cultures, a wedding ring is traditionally worn on the fourth digit, commonly called the "ring finger". This developed from the Roman anulus pronubis, when a man would give a ring to the woman at their betrothal ceremony. Blessing the wedding ring and putting it on the bride's finger dates from the 11th century.

In medieval Europe, during the Christian wedding ceremony, the ring was placed in sequence on the thumb, index, middle, and ring fingers of the left hand. The ring was then left on the ring finger.

In a few European countries, the ring is worn on the left hand prior to marriage, then transferred to the right during the ceremony. For example, an Eastern Orthodox Church bride wears the ring on the left hand prior to the ceremony, then moves it to the right hand after the wedding. In England, the 1549 Prayer Book declared "the ring shall be placed on the left hand". By the 17th and 18th centuries, the ring could be found on any digit after the ceremony — even on the thumb.

The wedding ring is generally worn on the ring finger of the left hand in the former British Empire, certain parts of Western Europe, certain parts of Catholic Mexico, Bolivia, Chile, and Central and Eastern Europe. These include: Australia, Botswana, Canada, Egypt, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa, the UK, and the US,[13] as well as France, Italy, Portugal, Sweden, Finland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Switzerland, Netherlands [if Catholic], Croatia, Slovenia, Romania, and the Catalan-speaking regions of Spain.

The wedding ring is worn on the ring finger of the right hand in some Orthodox and a small number of Catholic European countries, some Protestant Western European, as well as some Central and South American Catholic countries.[14] In Eastern Europe, these include Belarus, Bulgaria, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, North Macedonia, Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine. In Central or Western Europe, these include Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Poland, the Netherlands (if not Catholic), Norway, and Spain (except in the Catalan-speaking regions). In Central or South America, these include Colombia, Cuba, Peru, and Venezuela.

In Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Romania, and Brazil, the ring is worn on the right hand until the actual wedding day, when it is moved to the left hand.

In western guitar music, "I-M-A" is a style of plucking guitar strings, where "I" means index finger, "M" means middle finger, and "A" means ring finger. This is a popular type of "finger style" guitar playing, where the "A" comes from Latin, where the word anulus means ring.[15]

Middle Eastern, Jewish, and Asian customs

[edit]In Sinhalese and Tamil culture, the groom wears the wedding ring on his right hand, but the bride wears it on her left hand ring finger. This can be seen in countries like Sri Lanka, which has a rich Sinhalese and Tamil cultural influence on the society.[16]

A wedding ring is not a traditional part of the religious Muslim wedding, and wedding rings are not included in most Islamic countries. If a wedding ring is worn in an Islamic country, however, it may be worn on either the left (such is the custom in Iran) and for example (in Jordan the right ring finger for engagement and the left ring finger for marriage). As opposed to the wedding ring, use of a ring to denote betrothal or engagement is quite prevalent in Muslim countries, especially those in West and Asia. These rings may be worn on the ring finger of either the right or left hand by both men and women.

In a traditional Jewish wedding ceremony, the wedding ring is placed on the bride's right-hand index finger,[17] but other traditions place it on the middle finger or the thumb, most commonly in recent times.[18] Today, the ring usually is moved to the left hand ring finger after the ceremony. Some Jewish grooms have adopted wearing a wedding ring, but in Orthodox Judaism, most men do not wear wedding rings.

Rings are not traditional in an Indian wedding, but in modern society, it is becoming a practice to wear rings for engagements if not for actual marriage. Although the left hand is considered inauspicious for religious activities, a ring (which is not called a wedding ring) is still worn on the left hand. Men generally wear the rings on the right hand and women on the left hands.

See also

[edit]- Digit ratio, comparative lengths of the index finger and ring finger and androgen levels in utero

- Finger numbering

References

[edit]- ^ "Synonyms of ring finger | Thesaurus.com". www.thesaurus.com. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "ring finger". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "fourth finger". Medical Dictionary. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "How the 'Ring Finger' Got Its Name". Merriam Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "Synonyms of annulary | Thesaurus.com". www.thesaurus.com. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ Magyar, László A. (1990). "Digitus Medicinalis — the Etymology of the Name". Actes du Congr. Intern. d'Hist. de Med. XXXII., Antwerpen. pp. 175–179. Archived from the original on 23 January 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- ^ Bosnyák, Sándor (2021). A múló idő felett: válogatott tanulmányok. Budapest: Kairosz Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-514-095-4.

- ^ "Japanese Vocabularies: Talking about human body". Crunchy Nihongo!. 17 September 2017.

- ^ Kunz, George Frederick (1917). Rings for the finger: from the earliest known times, to the present, with full descriptions of the origin, early making, materials, the archaeology, history, for affection, for love, for engagement, for wedding, commemorative, mourning, etc. J. B. Lippincott company. pp. 193–194.

- ^ Mukherji, Subha (2006), Law and Representation in Early Modern Drama, Cambridge University Press, pp. 35–36, ISBN 0521850355

- ^ "Ruby And The Wolf". Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Wedding rings: Have men always worn them?". BBC. 8 April 2011.

World War II is considered to have heralded a seismic shift, as many Western men fighting overseas chose to wear wedding rings as a comforting reminder of their wives and families back home.

- ^ "What hand does a wedding ring go on for a man". Alpine Rings.

- ^ "Why in the Orthodox tradition do we wear the wedding ring on the left hand?". antiochian.org.

- ^ "Right Hand Planting Technique". douglasniedt.com.

- ^ "A Sri Lankan Tamil Hindu Wedding" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2012.

- ^ "Guide to the Jewish Wedding". aish.com. 9 May 2009.

- ^ Sperber, David (1995). Minhagei Yisrael, Jerusalem (Hebrew). Vol. 4. pp. 92–93.