John Joubert (serial killer)

John Joubert | |

|---|---|

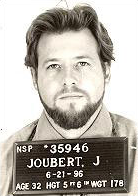

Joubert on June 21, 1996 | |

| Born | John Joseph Joubert IV July 2, 1963 Lawrence, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | July 17, 1996 (aged 33) |

| Cause of death | Execution by electrocution |

| Conviction(s) | Nebraska First degree murder (2 counts) Maine Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Nebraska Death Maine Life imprisonment |

| Details | |

| Victims | 3+ |

Span of crimes | August 22, 1982 – December 2, 1983 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Maine and Nebraska |

Date apprehended | January 12, 1984 |

John Joseph Joubert IV (July 2, 1963 – July 17, 1996) was an American serial killer executed in Nebraska. He was convicted of murdering three boys: one in Maine, and two in Nebraska.

Childhood

[edit]Joubert was born on July 2, 1963, in Lawrence, Massachusetts. He had one sister. In 1969, at the age of six, his parents divorced; in 1974, he and his sister moved with their mother to an unkempt, dilapidated apartment in Portland, Maine, to start a new chapter. Despite wanting to do so, Joubert was not allowed to visit his father, and grew to despise his controlling mother. "My impression was that the mother was cold and extremely manipulative", said Rich Pitre, Joubert's high school band teacher, friend, and mentor. "He was under a very, very tight leash".[1]

Though he was, by all accounts, an honor roll student and very driven academically, Joubert was targeted negatively by some of his peers; he would be bullied by bigger boys for seeming meek, shy, or otherwise helpless. According to his former Spanish teacher, Francesca Bergan, Joubert was "a 'little boy' all through his high school years", adding that "a lot of kids are picked on, but they seem to defend themselves... I think, because [John] did not defend himself... I wonder if he thought he deserved that kind of abuse that he would get... the shoving, the names, you know; the teasing.” [2]

Joubert sought to compensate for these feelings of isolation by becoming more involved, playing clarinet in the marching band, running on the school track team, as well as joining the Cub Scouts. It was around this time that his sadistic and homicidal fantasies progressed, to the point where he imagined murdering complete strangers on the streets, or of restraining and gagging those who resisted him. In one later psychiatric report, he was described as saying that he derived pleasure from the despair of his victims, saying that "if you are going to do it, get it over with".[3]

When he was 13, he stabbed a young girl with a pencil and felt sexually stimulated when she cried out in pain. The next day, armed with a razor blade, he slashed another girl as he biked past. He was never identified or charged in either offense. In another incident, he beat up another boy and nearly strangled him to the point of unconsciousness. Having been bullied throughout his youth, Joubert relished the physical and mental power of this dominance, and began to consider casually stabbing or slashing others.[4] He ultimately graduated from Cheverus High School, a Catholic secondary school in Portland, in 1981.[5]

Murders

[edit]On August 22, 1982, 11-year-old Richard "Ricky" Stetson left home to go jogging on the 3.5 mile long Back Cove Trail in Portland, Maine.[6][7] When he did not return by dark, his parents called the police. The next day, a motorist discovered the boy's body on the side of Interstate 295. The attacker had attempted to undress him, then stabbed, strangled, and bit him. A suspect was arrested for the murder but his teeth did not match the bite mark on Stetson's body, so he was released after one and a half years in custody. No additional leads presented themselves in the case until January 1984.

Danny Joe Eberle, 13 years old, disappeared while delivering copies of the Omaha World-Herald on Sunday, September 18, 1983, in Bellevue, Nebraska.[8] His brother, who also delivered papers, had not seen him, but he did remember being followed by a white man in a tan car on previous days. It was ascertained that Eberle had delivered only three of the 70 newspapers on his route. At the address of his fourth delivery, his bicycle was discovered along with the rest of the newspapers. There appeared to be no sign of a struggle. Joubert would later describe how he had approached Eberle, drawn a knife and covered the boy's mouth with his hand. He instructed Eberle to follow him to his car and drove him to a gravel road outside the town.

After a three-day search, Eberle's body was discovered in a patch of high grass alongside a gravel road some 4 miles (6 km) from his bicycle. He had been stripped to his undershorts, his feet and hands had been bound, and his mouth had been sealed with surgical tape. Knife wounds across his body suggested he had been tortured before death. In addition, Joubert had stabbed him nine times. As a kidnapping, the crime came under the jurisdiction of the federal government of the United States, so the FBI was called in.[9]

The investigation followed several leads, including a young man who was arrested for molesting two young boys approximately a week after the crime. He failed a polygraph test and had a false alibi, but did not fit the profile the FBI had created for the murderer. He was released due to a lack of evidence. Other known pedophiles in the area were questioned, but the case became cold due to a lack of evidence.

On December 2, 1983, Christopher Walden, age 12, disappeared in Papillion, Nebraska, approximately 3 miles (5 km) from where Eberle's body had been found.[10] Witnesses again said they saw a white man in a tan car. In his later confession, Joubert said that he had driven up to Walden as he walked, showed him the sheath of his knife, and ordered him into the car.

After driving to some railway lines out of town, he ordered Walden to strip to his undershorts, which he did, but then Walden refused to lie down in the snow. After a brief struggle, Joubert overpowered and then stabbed him. Joubert cut Walden's throat so deeply that he nearly decapitated the boy. Walden's body was found two days later, 5 miles (8 km) from the town. Although the crimes were similar, there were differences; Walden had not been bound, had been better concealed, and was thought to have been killed immediately after being abducted.

Arrest

[edit]On January 11, 1984, a preschool teacher in the area of the murders called police to say that she had seen a young man driving in the area. There are conflicting stories as to whether the car was loitering or just driving around. When the driver saw the teacher writing down his license plate, he stopped and threatened her, although she was able to run away from him. The car was not tan, but was traced and found to be rented by John Joubert, an enlisted radar technician from Offutt Air Force Base. It turned out that his own car, a tan Chevrolet Nova sedan, was being repaired.

A search warrant was issued, and rope consistent with that used to bind Danny Joe Eberle was found in his barracks room. The FBI found that the unusual rope had been made for the United States military in South Korea. Under interrogation, Joubert admitted obtaining it from the scoutmaster in the troop in which he was an assistant.

Robert K. Ressler, the FBI's head profiler at the time, along with Dr. Ann Burgess, had access to the information about the two boys in Nebraska and worked up a hypothetical description which matched Joubert in every regard. While presenting the case of the two Nebraska boys to a training class at the FBI Academy at Quantico, Virginia, a police officer from Portland, Maine, observed the similarities to a case in his jurisdiction which took place while Joubert had lived there prior to joining the Air Force. Bite mark comparisons proved that Joubert was responsible for the Maine killing in addition to those in Nebraska. Ressler and the Maine investigators came to believe that Joubert joined the military to get away from Maine after the murder of the Stetson boy.[11]

Further investigation in Maine revealed two crimes between the pencil stabbing of the nine-year-old girl in 1979 and the murder of Stetson in 1982. In 1980, Ressler's investigation revealed that Joubert had slashed a nine-year-old boy and a female teacher in her mid-twenties who both "had been cut rather badly, and were lucky to be alive."[11]

Trials and appeals

[edit]Joubert then confessed to killing the two Nebraska boys and, on January 12, 1984, was charged with their murders. After initially pleading not guilty, he changed his plea to guilty. There were several psychiatric evaluations performed on Joubert. One characterized him as having obsessive-compulsive disorder, sadistic tendencies, and schizoid personality disorder.[12]: 13

He was found to have not been psychotic at the time of the crimes. A panel of three judges sentenced him to death for both counts. After a trial, Joubert was also sentenced to life imprisonment in Maine (which did not have the death penalty) in 1990 for the murder of Ricky Stetson after Joubert's teeth were found to match the bite mark.[4]

In 1995, Joubert filed a writ of habeas corpus to the United States District Court for the District of Nebraska over the death sentences. His lawyers argued that the aggravating factor of "exceptional depravity" was unconstitutionally vague. The district court agreed, but the state of Nebraska appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. The appeals court overturned the district court decision, saying that he had clearly shown sadistic behavior by torturing Eberle and Walden.

Joubert was executed on July 17, 1996, by the state of Nebraska in the electric chair. He was the second person executed in Nebraska since the death penalty was reintroduced in the state in 1973.[13] Before his execution, Joubert made a final statement in which he apologized for the murders, saying "I just want to say that again I am sorry for what I have done. I do not know if my death will change anything or if it will bring anyone peace. And I just ask the families of Danny Eberle and Christopher Walden and Richard Stetson to please try to find some peace and ask the people of Nebraska to forgive me. That's all."[14] His last meal consisted of pizza with green peppers and onions, strawberry cheesecake and black coffee.[15]

An appeal to the Nebraska Supreme Court over whether the electric chair in Nebraska is a cruel and unusual punishment revealed that during his execution, Joubert developed a four-inch blister on the top of his head and blistering on both sides of his head above his ears.[16]

Media

[edit]Joubert's case was covered on Forensic Files in the season 4 episode "Ties That Bind" and in episode 2, "To Hunt a Killer", of Mastermind: To Think Like a Killer. It was also featured in season 24, episode 19 of Horizon, "Traces of Murder".

See also

[edit]- Capital punishment in Nebraska

- Capital punishment in the United States

- List of people executed in Nebraska

- List of serial killers in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ Very Local—content creator (20 March 2020). "Boy Scout Turned Serial Killer: The John Joubert Story I Dispatches From The Middle". YouTube. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

My impression was that the mother was cold and extremely manipulative; he was under a very, very tight leash.

- ^ Very Local—content creator (20 March 2020). "Boy Scout Turned Serial Killer: The John Joubert Story I Dispatches From The Middle". YouTube. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

He was a 'little boy' all through his high school years…a lot of kids are picked on, but they seem to defend themselves... and I think, because [John] did not defend himself, I wonder if he thought he deserved that kind of abuse that he would get... the shoving, the names, you know; the teasing.

- ^ Pettit, Mark (1990). A Need to Kill. New York City: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-8041-0785-3.

- ^ a b "How Notorious Serial Killer John Joubert's Days of Slaying Children Came to an End". The New York Daily News. September 17, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Maine authorities want to interview Joubert in Nebraska". Bangor Daily News. October 19, 1984. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved April 1, 2020 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ Ramsland, Katherine; McGrain, Patrick N. (December 21, 2009). Inside the Minds of Sexual Predators. Praeger, Frederick A. p. 64. ISBN 978-0313379604. Archived from the original on September 4, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Back Cove Trail". trails.org. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ^ "A 13-year-old's dead body turns up - Sep 21, 1983 - History.com". History.com. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ Evans, Colin (1998). The Casebook of Forensic Detection. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. p. 285. ISBN 0-471-07650-3.

- ^ "Kidnapped child's body found". UPI. December 6, 1983. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Ressler, Robert K.; Shachtman, Tom (1992). "Death of a Newsboy". Whoever Fights Monsters: My Twenty Years Hunting Serial Killers for the FBI. New York City: St. Martin's Press. pp. 93–112. ISBN 0312078838.

- ^ Ramsland, Katherine. "John Joubert, Nebraska Boy Snatcher". Crime Library. TruTv. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11.

- ^ "Child killer executed in Nebraska". UPI. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ "Joubert Dies For Boys' Murders" (PDF). July 17, 1996.

- ^ admin (2021-03-11). "Not a cereal in sight". Crime-ology. Retrieved 2021-12-20.

- ^ "Judge details why he thinks electric chair is a cruel penalty". 5 March 2004. Archived from the original on 2017-04-02. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- 1963 births

- 1996 deaths

- 20th-century executions by Nebraska

- American murderers of children

- Cheverus High School alumni

- Crime in Omaha, Nebraska

- Executed American serial killers

- Executed people from Massachusetts

- Incidents of violence against boys

- People convicted of murder by Maine

- People convicted of murder by Nebraska

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by Maine

- People executed by Nebraska by electric chair

- People from Lawrence, Massachusetts

- People from Portland, Maine

- People with obsessive–compulsive disorder

- People with schizoid personality disorder

- Serial killers from Maine

- Serial killers from Nebraska

- Violence against men in the United States