Ricky Lee

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Ricky Lee | |

|---|---|

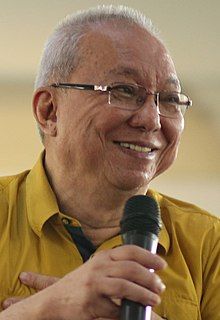

Lee at a screenwriting seminar in Colegio de San Juan de Letran, February 2018 | |

| Born | Ricardo Arreola Lee March 19, 1948 Daet, Camarines Norte, Philippines |

| Nationality | Filipino |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1973–present |

| Awards | |

Ricardo Arreola Lee ONA (born March 19, 1948) is a Filipino screenwriter, journalist, novelist, and playwright. He was awarded the Order of National Artists of the Philippines for Film and Broadcast Arts in 2022.[1]

Starting in 1973, he has written more than 180 film screenplays. In addition to the Order of National Artists, the Philippines' highest recognition for individuals who have made significant contributions to the classical arts, his work has earned him over 70 trophies from various award-giving bodies. This includes three lifetime achievement awards from the Cinemanila International Film Festival, the Gawad Urian, and the PMPC. He was also the recipient of the 2015 UP Gawad Plaridel and one of the Gawad CCP awardees for that year. In 2018, he received the Gawad Dangal ni Balagtas, the Apolinario Mabini Achievement Award, a Special Citation at ABS-CBN's Walk-On-Water Awards, and was one of the recipients of the CAMERA OBSCURA awards from the Film Development Council of the Philippines.[2]

As a screenwriter, he has collaborated with many of the Philippines' most notable film directors, including Lino Brocka, Marilou Diaz-Abaya, and Ishmael Bernal. Many of his films have been screened in international film festivals, including Cannes, Toronto, and Berlin, among others.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Lee grew up with his relatives in Daet, Camarines Norte. His mother died when he was five years old, and he saw his father only on a few occasions. He completed his primary and secondary education in the same town. It is said that Lee often sneaked into film houses and buried himself in books at the school library, tearing out pages with striking images. An intelligent student, he consistently topped his class from grade school to high school. His writing career began when he won his first national literary award for a short story he wrote while still in high school. Driven by his passion to pursue his dreams, he ran away from home and took a bus to Manila. He roamed the streets, taking on menial tasks as a waiter during the day and asking his townspeople for accommodation at night until he eventually collapsed in Avenida from hunger.

He was accepted at the University of the Philippines Diliman as an AB English major but never earned his diploma. Ironically, he later taught screenwriting at the College of Mass Communication.

He started writing fiction in the late 1960s, gaining confidence with the publication of his first short story, "Mayon," in the Philippine Free Press while he was still in high school. His early efforts earned him several national awards, including Third Place in the Pilipino Free Press for "Pagtatapos" (1969) and first prizes in consecutive years for the short story at the Don Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature for "Huwag, Huwag Mong Kukuwentuhan ang Batang si Weng Fung" (1969) and "Servando Magdamag" (1970).

A rare achievement for a writer, two of his short stories won first prizes at the Don Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature in two consecutive years, 1970 and 1971.

He became an activist during those politically turbulent times and was affiliated with Panulat para sa Kaunlaran ng Sambayanan (PAKSA, or Pen for People's Progress), alongside Bienvenido Lumbera and Jose F. Lacaba.[3]: 10

Imprisonment during Martial Law

[edit]Since Ferdinand Marcos was arresting numerous academics and writers when he placed the Philippines under martial law in 1972, Lee and Lumbera made themselves scarce and avoided being caught in the initial wave of arrests. However, they were both apprehended by Marcos' forces in 1974.[3]: 10 [4]

Lumbera had gone to Lee's house on España Boulevard to warn him about a recent wave of arrests, only to find that soldiers were already there arresting Lee. Lumbera ran away and made it as far as the corner of Banawe Street, but the soldiers eventually caught up with him.[5]

Lee later described the circumstances of his arrest, saying in Tagalog:[6]

"They asked, ‘Where’s your gun?’ I said, ‘I don’t know how to hold a gun, why would I have a gun? They would find reason even if it was not legitimate because when they captured you, they would call you detainees, not prisoners. There were no charges. You don’t know why. They would just detain you so you can’t move, you can’t be an activist. They’d detain you without any hearing, no charges, and you have no idea when you’d ever get out because you’re a detainee.[6]

Lee and Lumbera shared a cell at the Ipil Detention Center in Fort Bonifacio.[7][8] According to the recollections of many fellow detainees, Lee became very ill with rheumatic fever, and Lumbera is remembered for his efforts to take care of him.[7][8]

Lee and Lumbera were eventually released a year after their arrest.[7][8]

Lee and Lumbera eventually returned to the site of the Ipil Detention Center after Fort Bonifacio was privatized. They were amused to discover that the area where Ipil was located had become the vicinity of S&R and Home Depot, near 32nd Street and 8th Avenue in Bonifacio Global City.[9]

Release and post-detention work

[edit]Lee was released in 1975, and his friends Ninotchka Rosca and Rolando Tinio helped him reintegrate into life after detention and find work.[9]

He was a staff writer for the Pilipino Free Press in the 1970s. Throughout that turbulent decade and into the 1990s, he wrote features and interviews for Asia-Philippines Leader, Metro Magazine, Expressweek, TV Times, Malaya Midday, The National Midweek, Veritas, and Sunday Inquirer Magazine on topics as diverse as street children, vendors around Quiapo Church, an NPA commander, unsung workers in the film industry, a defunct Gala vaudeville-and-burlesque theater, film actors, an activist martyr during a tragic peasant protest march, and teenage prostitutes, as well as Director Lino Brocka, among others.

Lee started writing Himala soon after his release.[9] He cites his prison experiences as the reason for the film's themes,[9] recounting in a Rappler interview:[10]

"I was in prison for one year, so what I wrote in 1976 imbued my experience of being an activist, of being imprisoned for a year at Fort Bonifacio, the questioning, the struggling against this and that belief and so on and so forth" (Translated in reference)[10]

Lee spent six years looking for a producer for the film, but he had no success.[11] Eventually, the screenplay won a contest launched by the Experimental Cinema of the Philippines, which meant that Lee would ironically be working with Imee Marcos. Despite this irony, Lee remained silent to ensure the film would be produced. It was eventually released during the 1982 Metro Manila Film Festival.[9] The movie was highly successful during its run, receiving nine awards at the festival and becoming the first Philippine film to be included in the "Competition Section" of the 33rd Berlin International Film Festival in March 1983.[6][12]

At the turn of the decade, Lee was introduced to director Marilou Diaz-Abaya as the screenwriter for Brutal (1980), which premiered at the 1980 Metro Manila Film Festival and became very successful. This marked the beginning of a widely acclaimed feminist trilogy of films that included Moral (1982) and Karnal (1983), featuring Diaz-Abaya as director and Lee as screenwriter.[13][14] Lee's screenplay for Salome/Brutal won the 1981 Philippine National Book Award for Best Screenplay. This began a series of frequent collaborations between Diaz-Abaya and Lee, lasting until Diaz-Abaya's death in 2012, and saw both inducted into the Order of National Artists of the Philippines in 2022.

Lee wrote extensively over the next two and a half decades, with some of his most critically acclaimed works including Sandakot Na Bala (1988), co-written and directed by Jose Carreon; Dyesebel (1990); Juan Tamad at Mister Shooli: Mongolian Barbecue (1991); Mayor Cesar Climaco (1994); The Flor Contemplacion Story (1995); the psychological horror film Patayin sa Sindak si Barbara (1995); Sharon Cuneta starrer Madrasta (1996); and Labs Kita... Okey Ka Lang? (1998).

Later career

[edit]The late 1990s and early 2000s marked a period during which Lee penned screenplays for several highly acclaimed films, most notably the 1998 bio-epic José Rizal, which he co-wrote with Jun Lana and Peter Ong Lim; Muro-Ami (1999); Bulaklak ng Maynila (1999); the 2000 films Anak, Lagarista, and Deathrow; Mila, Tatarin, and Bagong Buwan (2001); and Aishite Imasu 1941: Mahal Kita (2004).

In 2000, he was one of the recipients of the Centennial Honors for the Arts from the Cultural Center of the Philippines and the Gawad Pambansang Alagad ni Balagtas for Tagalog fiction from the Unyon ng mga Manunulat sa Pilipinas.

In 2011, he was awarded the Manila Critics Circle Special Prize for a Book Published by an Independent Publisher. His two-stage plays Pitik-Bulag sa Buwan ng Pebrero and DH (Domestic Helper) played to standing-room-only crowds. DH, starring Nora Aunor, toured the U.S. and Europe in 1993.

In November 2008, he launched his first novel, Para kay B (o kung paano dinevastate ng pag-ibig ang 4 out of 5 sa atin), at the University of the Philippines-Diliman Bahay ng Alumni. This was followed exactly three years later by Si Amapola sa 65 na Kabanata, which was launched at the SM North EDSA Skydome and received similar public acclaim and support.[15]

In September 2024, he launched Kalahating Bahaghari (addressing the oppression and discrimination toward the LGBTQ+ community) and Kabilang sa mga Nawawa (or Among the Disappeared, about a teenager named Junjun, a “desaparecido”) at the Manila International Book Fair at the SMX Convention Center.[16]

Mentor

[edit]Since 1982, Lee has been conducting scriptwriting workshops for free at his home.[17] He challenges his students to push their boundaries and explore the limits of their imaginations until they feel as if they might drown. In one of his workshops in Tagaytay, participants were stuck on a concept that didn't seem to work. He refused to let the group eat until the concept was finished. Hunger, he says, does wonders for creativity; it makes you imagine things. To help them develop three-dimensional characters, he encourages his students to inhabit their characters by immersing themselves in the characters' world, either as observers, participants, or by acting out the roles of these characters in their own milieu. The more intrepid students may choose to act as a beggar in Quiapo, a bargirl in Ermita, or a squatter in Smokey Mountain, even for just one day, often with hilarious results. Participants leave the exercise a bit shaken but full of life-sustaining insights.

Ricardo Lee Film Festival

[edit]On January 22, 2008, filmmaker Nick Deocampo, director of the Mowelfund Film Institute (1989–2008) and Center for New Cinema (2008–present), announced the Ricardo Lee Film Festival, which would be held from February 4 to 10, 2008, as part of the World Arts Festival under Mayor Tito Sarion in Daet, Camarines Norte. Lee’s scripts became Philippine cinema classics, contributing to the second golden age of Filipino movies in the 1980s. Five films were shown at the festival: Gina Alajar's Salome, Anak, Muro Ami, Gumapang Ka sa Lusak, and Memories of Old Manila.[18]

Current affiliation

[edit]Lee previously worked as a Creative Manager at ABS-CBN Corporation. However, after the House of Representatives denied the network's franchise, he moved to GMA Network. He also established and heads the Trip to Quiapo Foundation, formerly known as the Philippine Writers Studio, which aims to provide support to new and struggling writers.

Body of work

[edit]His body of work, which has spanned over forty years, includes writing short stories, plays, essays, novels, teleplays, and screenplays. He has written more than 150 produced scripts, earning over fifty awards from various organizations in the Philippine movie industry. He has never written, nor will he ever write, any literary work in English—a conviction he holds to this day.

Books

[edit]Among the books he has published are Si Tatang at mga Himala ng Ating Panahon (an anthology of his fiction, reportage, behind-the-scenes musings, and the full screenplay of Himala), Pitik-Bulag Sa Buwan Ng Pebrero, Brutal/Salome (the first book of screenplays in the Philippines), Moral, Para Kay B, and Bukas May Pangarap. His screenplay for Salome has been translated into English and published by the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the U.S. as part of its textbook for film studies.

Lee has also published a screenplay manual titled Trip to Quiapo, which is a required text in many college communications courses.

Screenplays

[edit]- Dragnet (co-writer, uncredited; 1973)

- Itim (co-writer, uncredited; 1976)

- Pabonggahan (documentary; 1979)

- Jaguar (1979)

- Miss X (1980)

- Brutal (1980)

- Playgirl (1981)

- Carnival Queen (1981)

- Salome (1981)

- Karma (1981)

- PX (1982)

- Ito Ba ang Ating Mga Anak? (1982)

- Relasyon (1982)

- Cain and Abel (1982)

- Moral (1982)

- Himala (1982)

- Haplos (1982)

- Gabi Kung Sumikat ang Araw (1983)

- Karnal (1983)

- Sinner or Saint (1984)

- Baby Tsina (1984)

- Bukas... May Pangarap (1984)

- Silip: Daughters of Eve (1985)

- White Slavery (1985)

- Private Show (1985)

- Bomba Arienda (1985)

- Flesh Avenue (1986)

- Nasaan Ka Nang Kailangan Kita? (1986)

- Paano Kung Wala Ka Na? (1987)

- Olongapo... The Great American Dream (1987)

- The Untold Story of Melanie Marquez (1987)

- Kumander Dante (1988)

- Birds of Prey (1988)

- Sandakot Na Bala (with Jose Carreon, 1988)

- Babaing Hampaslupa (1988)

- Macho Dancer (1989)

- Hot Summer (1989)

- Sa Kuko ng Agila (1989)

- Virginia P. (1989)

- Ang Bukas Ay Akin Langit ang Uusig (1989)

- Dyesebel (1990)

- Nagsimula sa Puso (1990)

- Gumapang Ka sa Lusak (1990)

- Mundo Man ay Magunaw (1990)

- Beautiful Girl (1990)

- Hindi Laruan ang Puso (1990)

- Hahamakin Lahat (1990)

- Andrea, Paano Ba ang Maging Isang Ina? (1990)

- Pakasalan Mo Ako (1991)

- I Want to Live (1991)

- Class of '91 (1991)

- Hinukay Ko Na ang Libingan Mo! (1991)

- Juan Tamad at Mister Shooli: Mongolian Barbecue (1991)

- Ang Totoong Buhay ni Pacita M. (1991)

- Secrets of Pura (1991)

- Sa Aking Puso: The Marcos 'Bong' Manalang Story (1992)

- Kamay ni Cain (1992)

- Apoy sa Puso (1992)

- Ako ang Katarungan (Lt. Napoleon M. Guevarra) (1992)

- Narito ang Puso Ko (1992)

- Ayoko na Sanang Magmahal (1993)

- Because I Love You (1993)

- Inay (1993)

- Kung Kailangan mo Ako (1993)

- Pangako ng Kahapon (1994)

- Mayor Cesar Climaco (1994)

- Bawal na Gamot (1994)

- Loretta (1994)

- Midnight Dancers (1994)

- Separada (1994)

- Saan Ako Nagkamali? (1995)

- Minsan May Pangarap: The Guce Family Story (1995)

- Bawal na Gamot 2 (1995)

- The Flor Contemplacion Story (1995)

- Redeem Her Honor (1995)

- Mangarap Ka (1995)

- Muling Umawit ang Puso (1995)

- Patayin sa Sindak si Barbara (1995)

- Asero (1995)

- May Nagmamahal Sa'yo (1996)

- Sa Aking mga Kamay (1996)

- Utol (1996)

- Madrasta (1996)

- Lahar (1996)

- Hangga't May Hininga (1996)

- Nights of Serafina (1996)

- Kadre (1997)

- Sanggano (1997)

- Wala Ka Nang Puwang sa Mundo (1997)

- Ipaglaban Mo II: The Movie (1997)

- Hanggang Kailan Kita Mamahalin? (1997)

- Calvento Files: The Movie (1997)

- Mapusok (1998)

- Pusong Mamon (1998)

- Curacha: Ang Babaeng Walang Pahinga (1998)

- Miguel/Michelle (1998)

- Labs Kita... Okey Ka Lang? (1998)

- Magandang Hatinggabi (1998)

- José Rizal (1998)

- Sidhi (1999)

- Burlesk King (1999)

- 'Di Puwedeng Hindi Puwede! (1999)

- Hey Babe! (1999)

- Muro-Ami (1999)

- Bulaklak ng Maynila (1999)

- Minsan, Minahal Kita (2000)

- Anak (2000)

- Lagarista (2000)

- Deathrow (2000)

- ID (2001)

- Hostage (2001)

- Ooops, Teka Lang... Diskarte ko 'to! (2001)

- Luv Text (2001)

- Mila (2001)

- Huwag Kang Kikibo... (2001)

- Angels (2001)

- Tatarin (2001)

- Bagong Buwan (2001)

- May Pag-ibig Pa Kaya? (2002)

- Kung Ikaw Ay Isang Panaginip (2002)

- Then and Now (2003)

- I Will Survive (2004)

- Sabel (2004)

- Liberated 2 (2004)

- So... Happy Together (2004)

- Aishite Imasu 1941: Mahal Kita (2004)

- Dubai (2005)

- Twilight Dancers (2006)

- Wag Kang Lilingon (2006)

- Fuchsia (2009)

- Kamoteng Kahoy (2009)

- Bente (2009)

- Mamarazzi (2010)

- Sa 'yo Lamang (2010)

- Shake, Rattle and Roll Fourteen: The Invasion (Segment: "Pamana"; 2012)

- Burgos (2013)

- Lauriana (2013)

- Lihis (2013)

- Justice (2014)

- The Trial (2014)

- Ringgo: The Dog Shooter (2016)

- Iadya mo Kami (2016)

- Bes and the Beshies (2017)

- Culion (2019)

- Hindi Tayo Pwede (2020)

- A Tale of Filipino Violence (2022)

References

[edit]- ^ "Nora Aunor, Ricky Lee, Tony Mabesa among 8 new National Artists". RAPPLER. 2022-06-10. Archived from the original on 2022-06-10. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- ^ "FDCP Announces 2020 Camera Obscura Awardees". Film Development Council of the Philippines. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ a b Lee, Ricky (2012). Lee, Ricky (ed.). Sa Puso ng Himala (in Filipino and English). Loyola Heights, Quezon City, Philippines: Philippine Writer's Studio Foundation. ISBN 978-971-94307-3-5.

- ^ "Ricky Lee, martial law detainee, on historical revisionism: 'Para akong binubura' │ GMA News Online". 16 September 2021.

- ^ Lucas, Andrea Joyce (2021-09-28). "Bienvenido Lumbera, the People's Scholar". Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- ^ a b c "Ricky Lee, martial law detainee, on historical revisionism: 'Para akong binubura'". 16 September 2021.

- ^ a b c "Detention Camp 2Manila Today | Manila Today". www.manilatoday.net. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Renee Nuevo. "Bienvenido Lumbera, National Artist for Literature, Has Passed Away - The poet, literary critic, and cultural icon was 89".

- ^ a b c d e "Screenwriter Ricky Lee lived 3 lives in detention". 22 September 2014.

- ^ a b "For Ricky Lee, 'Himala,' the film he wrote during Martial Law, still relevant today". 21 September 2019.

- ^ Jerome Gomez. "'Don't be afraid to enter the wrong door,' and more Ricky Lee advice that could change your life - In his latest book, "Kulang Na Silya" we are introduced to the award-winning scriptwriter as problem solver and veteran advice-giver". Archived from the original on 2021-04-17.

- ^ "Why Ricky Lee wants to rewrite 'Himala'". The Philippine STAR.

- ^ "Ricky Lee turns emotional at book launch of his classic screenplays". Daily Tribune. 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Philippine Cinema Through the Eyes of Ricky Lee".

- ^ "Ricky Lee: In Flight". 3 January 2012.

- ^ Agcaoili, Nicole (September 16, 2024). "Celebrities attend Ricky Lee's latest book launch". ABS-CBN. Retrieved September 18, 2024.

- ^ "Interview with Scriptwriter and Novelist Ricky Lee".

- ^ "Abs-Cbn Interactive, Ricky Lee to be honored in Daet arts festival".

External links

[edit]- National Artists of the Philippines

- 1948 births

- Living people

- Bicolano people

- Bikolano writers

- Filipino people of Chinese descent

- Filipino writers

- Marcos martial law prisoners jailed at Ipil Detention Center

- Marcos martial law victims

- People from Camarines Norte

- Tagalog-language writers

- University of the Philippines Diliman alumni

- ABS-CBN people

- GMA Network (company) people