Madoc

Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd (also spelled Madog) was, according to folklore, a Welsh prince who sailed to the Americas in 1170, over 300 years before Christopher Columbus's voyage in 1492.

According to the story, Madoc was a son of Owain Gwynedd who went to sea to flee internecine violence at home. The "Madoc story" evolved from a medieval tradition about a Welsh hero's sea voyage, to which only allusions survive. The story reached its greatest prominence during the Elizabethan era when English and Welsh writers wrote of the claim Madoc had gone to the Americas as an assertion of prior discovery, and hence legal possession, of North America by the Kingdom of England.[1][2]

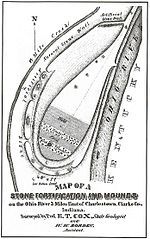

The Madoc story remained popular in later centuries, and a later development said Madoc's voyagers had intermarried with local Native Americans, and that their Welsh-speaking descendants still live in the United States. These "Welsh Indians" were credited with the construction of landmarks in the Midwestern United States, and a number of white travellers were inspired to search for them. The Madoc story has been the subject of much fantasy in the context of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact theories. No archaeological, linguistic, or other evidence of Madoc or his voyages has been found in the New or Old World but legends connect him with certain sites, such as Devil's Backbone on the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky.[3]

Family story

[edit]

Owain Gwynedd, who according to the legend was Madoc's father, was a real 12th-century king of Gwynedd and is considered one of the greatest Welsh rulers of the Middle Ages. Owain's reign was fraught with battles with other Welsh princes and with Henry II of England. At his death in 1170, a bloody dispute broke out between Owain's heir Hywel the Poet-Prince, and Owain's younger sons Maelgwn and Rhodri—children of the Princess-Dowager Cristen ferch Gronwy—and was led by Dafydd, the child of Gwladus ferch Llywarch.[4][5] Owain had at least 13 children from his two wives and several more children were born out of wedlock but legally acknowledged under Welsh tradition. According to the legend, Madoc and his brother Rhirid or Rhiryd were among them, though no contemporary record attests to this.

Background

[edit]The poet Llywarch ap Llywelyn of the 12th and 13th centuries did mention someone of this name as someone who fought in the Conwy, North Wales, during the time of Madoc's nephew, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth in the early 12th century. Supposedly Madoc had left his homeland in Wales after the death of his father, the King Owain Gwynedd, and sailed for nearby Ireland across the Irish Sea from North Wales then into the North Atlantic to then settle what would become New Spain.[6] According to the legend, Madoc and his brother (Rhirid or Rhiryd) were among the Welsh Britons who sailed from Rhos-on-Sea (Aber-Kerrik-Gwynan) in 1170 to Mobile Bay, Alabama in the United States of America. Then Madoc returned to set sail once again the following year from Lundy Island returning to Mobile Bay for his third Transatlantic crossing.[7] Although no contemporary record attests to this.[6]

Voyages attestation

[edit]Mediaeval texts

[edit]The earliest certain reference to a seafaring man named Madoc or Madog occurs in a cywydd by the Welsh poet Maredudd ap Rhys (fl. 1450–1483) of Powys that mentions a Madog who was a descendant of Owain Gwynedd and who voyaged to the sea. The poem is addressed to a local squire, thanking him on a patron's behalf for a fishing net. Madog is referred to as "Splendid Madog ... / Of Owain Gwynedd's line, / He desired not land ... / Or worldly wealth but the sea".[citation needed]

In around 1250 to 1255, a Flemish writer called Willem[8] identifies himself in his poem Van den Vos Reinaerde as "Willem die Madoc maecte" (Willem, the author of Madoc, known as "Willem the Minstrel"[A]). Though no copies of Willem's "Madoc" survive, according to Gwyn Williams: "In the seventeenth century a fragment of a reputed copy of the work is said to have been found in Poitiers". The text provides no topographical details about North America but says Madoc, who is not related to Owain in the fragment, discovered an island paradise, where he intended "to launch a new kingdom of love and music".[10][11] There are also claims the Welsh poet and genealogist Gutun Owain wrote about Madoc before 1492. Gwyn Williams in Madoc, the Making of a Myth said Madoc is not mentioned in any of Gutun Owain's surviving manuscripts.[12]

Elizabethan and Stuart claims to the New World

[edit]The Madoc legend reached its greatest prominence during the Elizabethan era, when Welsh and English writers used it to bolster British claims in the New World against those of Spain. The earliest-surviving full account of Madoc's voyage, the first to make the claim Madoc visited America before Columbus,[B] appears in Humphrey Llwyd's Cronica Walliae (published in 1559),[14] an English adaptation of the Brut y Tywysogion.[15][C]

John Dee used Llwyd's manuscript when he submitted the treatise "Title Royal" to Queen Elizabeth I in 1580, which stated: "The Lord Madoc, sonne to Owen Gwynned, Prince of Gwynedd, led a Colonie and inhabited in Terra Florida or thereabouts" in 1170.[1] The story was first published by George Peckham as A True Report of the late Discoveries of the Newfound Landes (1583) and, like Dee, it was used to support English claims to the Americas.[17] The story was picked up in David Powel's Historie of Cambria (1584),[17][D] and Richard Hakluyt's The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589). According to Dee, not only Madoc, but also Brutus of Troy and King Arthur, had conquered lands in the Americas and therefore their heir Elizabeth I had a priority claim there.[19][20]

According to the 1584 Historie of Cambria by David Powel, Madoc was disheartened by this family fighting, and he and Rhirid set sail from Llandrillo (Rhos-on-Sea) in the cantref of Rhos to explore the western ocean.[E] In 1770, they purportedly discovered a distant, abundant land where about 100 men, women and children disembarked to form a colony. According to Cronica Walliae and many other copied sources, Madoc and some others returned to Wales to recruit additional settlers.[21] After gathering eleven ships and 120 men, women and children, Madoc and his recruiters sailed west a second time to "that Westerne countrie", and ported in "Mexico", a claim Reuben T. Durrett cited in his work Traditions of the earliest visits of foreigners to north America,[22] and stated Madoc never returned again to Wales.[23]

In 1624, John Smith, a historian of Virginia, wrote of the Chronicles of Wales reports Madoc went to the New World in 1170, over 300 years before Columbus, with some men and women. Smith says the Chronicles say Madoc returned to Wales to get more people and travelled back to the New World.[24][25] In the late 1600s, Thomas Herbert popularised the stories told by Dee and Powel, adding more detail from unknown sources, suggesting Madoc may have landed in Canada, Florida, or Mexico, and reporting Mexican sources stated they used currachs.[26]

"Welsh Indians" as potential descendants

[edit]As immigrants came into contact with more groups of Native Americans in the United States, at least thirteen real tribes, five unidentified tribes, and three unnamed tribes have been suggested as "Welsh Indians".[27][28] Eventually, the legend settled on identifying the Welsh Indians with the Mandan people, who were said to differ from their neighbours in culture, language, and appearance.[29] Although several attempts to confirm Madoc's historicity have been made, historians of early America including Samuel Eliot Morison made the assertion that the voyage story could be a fictional.[30] Suggestions of potential descendants are as follows:

On 26 November 1608, Peter Wynne, a member of Captain Christopher Newport's exploration party to the villages of the Monacan people—Virginia Siouan speakers above the falls of the James River in Virginia—wrote a letter to John Egerton informing him some members of Newport's party believed the pronunciation of the Monacans' language resembled "Welch", which Wynne spoke, and asked Wynne to act as an interpreter. The Monacan were among those non-Algonquian tribes the Algonquians collectively referred to as "Mandoag".[27] The Monacan tribe spoke to Wynne about the lore of the Moon-eyed people who were short bearded men with blue eyes and pale skin, they were sensitive to light and only emerged at night. The story has been associated with the legend of the Welsh settlement of Madog in the Great Smoky Mountains within the Appalachian Mountains.[31][32]

The Reverend Morgan Jones told Thomas Lloyd, William Penn's deputy, he had been captured in 1669 in North Carolina by members of a tribe identified as the Doeg, who were said to be a part of the Tuscarora. There is no evidence the Doeg proper were part of the Tuscarora.[33]) According to Jones, the chief spared his life when he heard Jones speak Welsh, which he understood. Jones' report says he lived for several months with the Doeg, preaching the Gospel in Welsh, and then returned to the British Colonies, where he recorded his adventure in 1686. Jones's text was printed by The Gentleman's Magazine, launching a slew of publications on the subject.[34] The historian Gwyn A. Williams commented: "This is a complete farrago and may have been intended as a hoax".[35]

Thomas Jefferson had heard of Welsh-speaking Indian tribes. In a letter written to Meriwether Lewis on 22 January 1804, Jefferson wrote of searching for the Welsh Indians who were "said to be up the Missouri".[36][37] The historian Stephen E. Ambrose wrote in his history book Undaunted Courage Jefferson believed the "Madoc story" to be true, and instructed the Lewis and Clark Expedition to find the descendants of the Madoc Welsh Indians. Neither they nor John Evans found any.[38][39][40]

In 1810, John Sevier, the first Governor of Tennessee, wrote to his friend Major Amos Stoddard about a conversation he had in 1782 with the Cherokee chief Oconostota concerning ancient fortifications along the Alabama River. According to Sevier, the chief said the forts were built by a white people called "Welsh" as protection against the ancestors of the Cherokee, who eventually drove them from the region.[41] In 1799, Sevier had written of the discovery of six skeletons in brass armour bearing the coat of arms of Wales,[7] and that Madoc and the Welsh were first in Alabama.[42]

In 1824, Thomas S. Hinde wrote a letter to John S. Williams, editor of The American Pioneer, regarding the Madoc tradition. In the letter, Hinde claimed to have gathered testimony from sources that stated Welsh people under Owen Ap Zuinch had travelled to America in the twelfth century, over 300 years before Christopher Columbus. According to Hinde, in 1799 near Jeffersonville, Indiana on the Ohio River, six soldiers were exhumed with breastplates that bore Welsh coats of arms.[43]

At least thirteen real tribes, five unidentified tribes, and three unnamed tribes have been suggested as "Welsh Indians".[28] The legend eventually settled on identifying the Welsh Indians with the Mandan people, who were said to differ from their neighbours in culture, language, and appearance. According to the painter George Catlin in North American Indians (1841), the Mandans were descendants of Madoc and his fellow voyagers; Catlin found the round Mandan Bull Boat similar to the Welsh coracle, and he thought the advanced architecture of Mandan villages must have been learnt from Europeans; advanced North American societies such as the Mississippian and Hopewell traditions were not well known in Catlin's time. Supporters of this claim have drawn links between Madoc and the Mandan mythological figure "Lone Man" who, according to one tale, protected some villagers from a flooding river with a wooden corral.[29]

The Welsh Indian legend was revived in the 1840s and 1850s; this time George Ruxton (Hopis, 1846), P. G. S. Ten Broeck (Zunis, 1854), and Abbé Emmanuel Domenach (Zunis, 1860), among others, claimed the Zunis, Hopis, and Navajo were of Welsh descent.[44] Brigham Young became interested in the supposed Hopi-Welsh connection; in 1858, Young sent a Welshman with Jacob Hamblin to the Hopi mesas to check for Welsh-speakers there. None were found but in 1863, Hamblin took three Hopi men to Salt Lake City, where they were "besieged by Welshmen wanting them to utter Celtic words", to no avail.[44] Llewelyn Harris, a Welsh-American Mormon missionary who visited the Zuni in 1878, wrote they had many Welsh words in their language, and that they claimed their descent from the "Cambaraga"—white men who had arrived by sea 300 years before the Spanish. Harris's claims have never been independently verified.[45] Several attempts to confirm Madoc's historicity have been made but historians of early America, notably Samuel Eliot Morison, regard the story as a myth.[30]

Modern developments

[edit]

According to Fritze (1993), Madoc's landing place has been suggested to be "Mobile, Alabama; Florida; Newfoundland; Newport, Rhode Island; Yarmouth, Nova Scotia; Virginia; points in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean including the mouth of the Mississippi River; the Yucatan; the isthmus of Tehuantepec, Panama; the Caribbean coast of South America; various islands in the West Indies and the Bahamas along with Bermuda; and the mouth of the Amazon River".[46] Madoc's people are reported to be the founders of various civilisations such as the Aztec, the Maya, and the Inca.[46]

American settlement myths

[edit]

The tradition of Madoc's purported voyage was he left Wales in 1170 to land in Mobile Bay in Alabama, USA and then travelled up the Coosa River which connections several southern counties of Alabama, Tennessee and Georgia. A legend passed down through generations of American Indians was of 'yellow-haired giants' who had briefly settled in Tennessee, then moved to Kentucky and then Southern Indiana, also involving the area of Southern Ohio, all of which became known as "The Dark and Forbidden Land", specifically the area of "Devil's Backbone" on the Ohio River. The story was passed on from the native American Chief Tobacco of the Piankeshaw tribe to George Rogers Clark who settled the city Clarksville, Indiana around the 1800s. The Chief spoke of a great battle between White and Red Indians, where the White Indians were slain. Supposedly, a graveyard of thousands of skeletons was found by Maj. John Harrison, but later washed away in a flood. Clark and the early settlers of his county had found European armor-clad skeletons thought to be ancient Welshmen, as well as ancient coins. According to local Cherokee tradition, the medieval settlers intermarried with the natives in Chattanooga, Tennessee and built stone forts there. It was said the modern 19th century settlers found Natives throughout the area who could converse in the Welsh language.[47][48] Details of the discoveries are as follows:

- According to a folk tradition, a site called "Devil's Backbone" at Rose Island, about fourteen miles (23 km) upstream from Louisville, Kentucky, was once home to a colony of Welsh-speaking Indians. The eighteenth-century Missouri River explorer John Evans of Waunfawr in Wales took up his journey in part to find the Welsh-descended "Padoucas" or "Madogwys" tribes.[49]

- In north-west Georgia, legends of the Welsh have become part of a myth surrounding the unknown origin of a rock formation on Fort Mountain. According to the historian Gwyn A. Williams, author of Madoc: The Making of a Myth, a Cherokee tradition concerning that ruin may have been influenced by contemporaneous European-American legends of "Welsh Indians".[50] The Georgia-based journalist Walter Putnam mentioned the Madoc legend in 2008.[51] The story of Welsh explorers is one of several legends about that site.

- In north-eastern Alabama, there is a story the Welsh Caves in DeSoto State Park were built by Madoc's party; local native tribes were not known to have practices such stonework or excavation that was found on the site.[52]

Legacy

[edit]Modern commemorations in honour of Madog ap Owain Gwynedd:

- In the United Kingdom during the early 1800s, a Member of Parliament for Boston, Lincolnshire and industrialist, William Alexander Madocks developed the area called Traeth Mawr into the towns of Madock's Port and Madock's Town in the Welsh county of Gwynedd. But in recent years, the towns assumed the Welsh naming of Porthmadog (port) and Tremadog (town) in honour of Madog ab Owain Gwynedd. The association with Prince Madoc and the towns is that he supposedly returned to Wales and was buried in the area that is now known as the town of Porthmadog.[53][54]

- The township of Madoc, Ontario, and the nearby village of Madoc in Canada (North America) are both named in the prince's memory.[55][56] As are several local guest houses and pubs throughout North America and the United Kingdom.

- In Rhos-on-Sea, Wales (UK), a boat-themed bench, sculpture and plaque introudced in 2023 commemorates the location where Prince Madog sailed from on his voyage. The plaque reads:[57]

Prince Madoc sailed from here Aber - Kerrick - Gwynan 1170 AD and landed at Mobile (Bay), Alabama with his ships Gorn Gwynant and Pedr Sant.

- The research vessel RV Prince Madog, which is owned by Bangor University and P&O Maritime, entered service in 2001,[58] replacing an earlier research vessel of the same name that first entered service in 1968.[59]

- In 1953, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) erected a plaque at Fort Morgan on the shore of Mobile Bay, Alabama, reading: "In memory of Prince Madoc a Welsh explorer who landed on the shores of Mobile Bay in 1170 and left behind with the Indians the Welsh language".[44][60] Alabama Parks Service removed the plaque in 2008, either because of a hurricane[61] or because the site focuses on the period 1800 to 1945,[62] and put in storage. It is now on display at the DAR headquarters in Mobile, Alabama.[63]

- The plaque cites Sevier's claims about the "people called Welsh". A similar plaque was placed in Fort Mountain State Park, Georgia, at the supposed site of one of Madoc's three stone fortresses. This plaque was removed in 2015 and the replacement does not mention Madoc.[64]

In literature

[edit]Fiction

[edit]- Knight, Bernard (1977). Madoc, Prince of America. New York City: St. Martin's Press.

- L'Engle, Madeleine (1978). A Swiftly Tilting Planet. New York: Dell Publishing. ISBN 0-440-40158-5.

- Pat Winter (1990). Madoc. New York City: Bantam. ISBN 978-0-413-39450-7.

- Pat Winter (1991). Madoc's Hundred. New York: Bantam. ISBN 978-0-553-28521-5.

- Thom, James Alexander (1994). The Children of First Man. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-37005-1.

- Waldo, Anna, ed. (1999). Circle of Stones. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-97061-1.

- Waldo, Anna Lee, ed. (2001). Circle of Stars. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-20380-1.

- Pryce, Malcolm (2005). With Madog to the New World. Y Lolfa. ISBN 978-0-862-43758-9.

- Clement-Moore, Rosemary, ed. (2009). The Splendor Falls. Delacorte Books for Young Readers. ISBN 978-0-385-73690-9.

Juvenile

[edit]- Thomas, Gwyn; Jones, Margaret (2005). Madog. Tal-y-bont, Ceredigion: Y Lolfa. ISBN 0-86243-766-0.

Poetry

[edit]Madoc's legend has been a notable subject for poets, however. The most famous account in English is Robert Southey's long 1805 poem Madoc, which uses the story to explore the poet's freethinking and egalitarian ideals. He had heard his story from Dr. W O Pughe.[65][66] Southey wrote Madoc to help finance a trip of his own to America,[67] where he and Samuel Taylor Coleridge hoped to establish a Utopian state they called a "Pantisocracy". Southey's poem in turn inspired the twentieth-century poet Paul Muldoon to write Madoc: A Mystery, which won the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize in 1992. It explores what might have happened if Southey and Coleridge had succeeded in coming to America to found their "ideal state".[68][69]

In Russian, the noted poet Alexander S. Pushkin composed a short poem "Madoc in Wales" (Медок в Уаллах, 1829) on the topic.[70]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "The earliest existing fragments of the epic of 'Reynard the Fox' were written in Latin by Flemish priests, and about 1250 a very important version in Dutch was made by Willem the Minstrel, of whom it is unfortunate that we know no more, save that he was the translator of a lost romance, 'Madoc'."[9]

- ^ "An so his was by Britons longe afore discovered before eyther Colonus or Americus lead any Hispaniardes thyther."[13]

- ^ "And at this tyme an other of Owen Gwynedhs sonnes, named Madocke, left the lande in contention betwixt his bretherne, and prepared certaine shippes, with men [and] munition, and sought adventures by the seas. And sayled west levinge the cost of Irelande [so far] north that he came to a land unknown, where he sawe many starange things. And this lande most needs be some parte of that land the which the Hispaniardes do affirme them selves to be the first finders, sith Hannos tyme. For by reason and order of cosmosgraphie this lande to which Madoc came to, most needs bee somme parte of Nova Hispania, or Florida."[16]

- ^ "This Madoc arriving in the Western country, unto the which he came, in the yeare 1170, left most of his people there: and returning back for more of his nation, acquaintance, and friends, to inhabite that faire and large countrie: went thither againe with ten sailes, as I find noted by Gutyn Owen. I am of opinion that the land, where unto he came, was part of Mexico; the causes which make me to think so be these."[18]

- ^ "And after he had returned home and declared the pleasant and frutefull countreys that he had seene without inhabitants, and upon the contrarye parte what barreyne and wilde grounde his bretherne and nevewes did murther one an other for, he prepared a number of shippes, and gote with suche men and women as were diserouse to lyve in quietness. And takinge his leave of his frends, toke his journey thytherwarde againe wherefore his is to be presupposed that he and his people enhabited parte of those countreys."[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Fowler 2010, p. 54.

- ^ Owen & Wilkins 2006, p. 546.

- ^ Curran 2008.

- ^ Pierce 1959.

- ^ Lloyd 1959.

- ^ a b Lee 1893.

- ^ a b History UK n.d.

- ^ Williams 1979, p. 51,76.

- ^ Gosse 1911.

- ^ Gaskell 2000, p. 47.

- ^ Williams 1979, p. 51, 76.

- ^ Williams 1979, p. 48-9.

- ^ a b Llwyd & Williams 2002, p. 168.

- ^ Llwyd & Williams 2002, p. vii.

- ^ Bradshaw 2003, p. 29.

- ^ Llwyd & Williams 2002, p. 167-68.

- ^ a b Morison 1971, p. 106.

- ^ Powel 1811, p. 167.

- ^ MacMillan 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Barone n.d.

- ^ Llwyd 1833, p. 80,81.

- ^ Durrett 1908, p. 124-150.

- ^ Powel 1811, pp. 166–7.

- ^ Durrett 1908, pp. 28, 29.

- ^ Smith 2006, p. 1.

- ^ Fritze 1993, p. 119.

- ^ a b Mullaney 1995, p. 163.

- ^ a b Fritze 2009, p. 79.

- ^ a b Bowers 2004, p. 163.

- ^ a b Curran 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Moon 2024.

- ^ appalachia 2024.

- ^ Fritze 1993, p. 267.

- ^ Greenwood 1898.

- ^ Williams 1979, p. 76.

- ^ Jefferson 1903, p. 441.

- ^ Roper 2003.

- ^ Williams 1963, p. 69.

- ^ Ambrose 1996, p. 285.

- ^ Kaufman 2005, p. 570.

- ^ Sevier 1810.

- ^ Williams 1979, p. 84.

- ^ Williams 1842, p. 373.

- ^ a b c Fowler 2010, p. 55.

- ^ McClintock 2007, p. 72.

- ^ a b Fritze 1993, p. 163.

- ^ LaTimes 1989.

- ^ News&Tribute 2008.

- ^ Kaufman 2005, p. 569.

- ^ Williams 1979, p. 86.

- ^ Putnam 2008.

- ^ Fritze 2011.

- ^ whr 2024.

- ^ BBC 2013.

- ^ Hamilton 1978, p. 157.

- ^ mindcat 2024.

- ^ daily 2024.

- ^ Bangor 2001.

- ^ Bangor n.d.

- ^ Morison 1971, p. 85.

- ^ BBC News 2008a.

- ^ BBC News 2008b.

- ^ Sledge 2020.

- ^ Sanders 2021, p. 15.

- ^ Lee 1893, p. 303.

- ^ Pratt 2007, pp. 133, 298.

- ^ Morison 1971, p. 86.

- ^ O'Neill 2007, pp. 145–16.

- ^ Southey 1805.

- ^ Wachtel 2011, pp. 146–151.

Sources

[edit]- Ambrose, Stephen E. (15 February 1996). Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the opening of the American West. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0684811073.

- Bowers, Alfred (1 October 2004). Mandan social and ceremonial organization. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6224-9.

- Bradshaw, Brendan (18 December 2003). British Consciousness and Identity: The Making of Britain, 1533–1707. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89361-9. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Curran, Bob (20 August 2010). Mysterious Celtic Mythology in American Folklore. Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58980-917-8.

- Curran, Kelly (8 January 2008). "The Madoc legend lives in Southern Indiana: Documentary makers hope to bring pictures to author's work". News and Tribune. Jeffersonville, Indiana. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- Davies, A. (1984). "Prince Madoc and the discovery of America in 1477". Geographical Journal. 150 (3): 363–72. Bibcode:1984GeogJ.150..363D. doi:10.2307/634332. JSTOR 634332.

- Durrett, Reuben Thomas (1908). Traditions of the Earliest Visits of Foreigners to North America, the First Formed and First Inhabited of the Continents. J.P. Morton & Company (Incorporated) printers to the Filson Club. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Fowler, Don D. (15 September 2010). Laboratory for Anthropology: Science and Romanticism in the American Southwest, 1846–1930. Utah Press, Universi. ISBN 978-1-60781-035-3.

- Franklin, Caroline (2003): "The Welsh American Dream: Iolo Morganwg, Robert Southey and the Madoc legend." In English romanticism and the Celtic world, ed. by Gerard Carruthers and Alan Rawes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 69–84.

- Fritze, Ronald H. (1993). Legend and lore of the Americas before 1492: an encyclopedia of visitors, explorers, and immigrants. ABC-CLIO. p. 119. ISBN 978-0874366648.

- Fritze, Ronald H. (15 May 2009). Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science and Pseudo-religions. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-674-2.

- Fritze, Ronald (21 March 2011). "Prince Madoc, Welsh Caves of Alabama". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Athens State University. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Gaskell, Jeremy (2000). Who Killed the Great Auk?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-856478-2. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- Ginanni, Claudia (26 January 2006). "Pulitzer prize poet Paul Muldoon to read". Bryn Mawr Now. Bryn Mawr College. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 719–729.

see page 719, lines 18–20

- Greenwood, Isaac J. (1898). The Rev. Morgan Jones and the Welsh Indians of Virginia. Boston: David Clapp & Son. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- Hamilton, William (1978). The Macmillan Book of Canadian Place Names. Toronto: Macmillan. pp. 157. ISBN 0-7715-9754-1.

- "The discovery of America by Welsh Prince Madoc". History Magazine. History UK. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1903). The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. Issued under the auspices of the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association of the United States. p. 441.

- Jones (1887). The Cambrian: A Magazine for the Welsh in America. D.I. Jones. p. 302.

- Kaufman, Will (31 March 2005). Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, And History: A Multidesciplinary Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 569. ISBN 978-1-85109-431-8.

- Llwyd, Angharad (1833). The history of the island of Mona. pp. 80–81. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- Llwyd, Humphrey; Williams, Ieuan (2002). Cronica Walliae (Print). Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1638-2.

- MacMillan, Ken (April 2001). "Discourse on history, geography, and law: John Dee and the limits of the British empire, 1576–80". Canadian Journal of History. 36 (1): 1. doi:10.3138/cjh.36.1.1.

- McClintock, James H. (31 October 2007). Mormon Settlement in Arizona: A Record of Peaceful Conquest of the Desert. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-4264-3657-4.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1971). The European Discovery of America. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Mullaney, Steven (1995). The Place of the Stage: License, Play and Power in Renaissance England. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08346-6.

- Newman, Marshall T (1950). "The Blond Mandan: A Critical Review of an Old Problem". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 6 (3): 255–272. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.6.3.3628461. S2CID 163656454.

- O'Neill, Michael (27 September 2007). The All-Sustaining Air: Romantic Legacies and Renewals in British, American, and Irish Poetry Since 1900. OUP Oxford. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-0-19-929928-7.

- Owen, Edward; Wilkins, Charles (2006) [December 1885]. "The Story of Prince Madoc's Discovery of America". The Red dragon, the national magazine of Wales. Vol. VIII, no. 6. Oxford University. p. 546.

- "Paul Muldoon". Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Powel, David (1811). The historie of Cambria, now called Wales [by St. Caradoc] tr. by H. Lhoyd, corrected, augmented, and continued, by D.Powel. Harding.

- Pratt, Lynda (1 November 2007). Robert Southey and the Contexts of English Romanticism. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-7546-8184-7. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Putnam, Walter (29 December 2008). "Mystery surrounds North Georgia ruins". Athens Banner-Herald. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- Roper, Billy (11 June 2003). "The Mystery of the Mandans". 100777. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- Sanders, Vivienne (15 July 2021). Wales, the Welsh and the Making of America. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-78683-791-2.

- Sevier, John (1810). "John Sevier letter to Amos Stoddard". Digital Public Library of America.

- Sledge, John (2020). "Madoc's Mark: The Persistence of an Alabama Legend". Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- Smith, John (13 October 2006). The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, & The Summer Isles. Applewood Books. ISBN 978-1-55709-362-2. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Smith, Philip E. (1962). University of Georgia – Laboratory of Archaeology Series. Report No. 4. Laboratory of Archaeology, Department of Sociology and Anthropology. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Southey, Robert (1805). Madoc. Edinburgh: Longman.

- Wachtel, Michael (2011). A commentary to Pushkin's lyric poetry, 1826–1836. University of Wisconsin Pres. ISBN 978-0-299-28544-9.

- Williams, David (1963). John Evans and the legend of Madoc, 1770–1799. University of Wales Press. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Williams, Gwyn A. (1979). Madoc: The Making of a Myth. Eyre Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-39450-7. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Williams, John S. (1842). The American Pioneer: A Monthly Periodical, Devoted to the Objects of the Logan Historical Society; Or, to Collecting and Publishing Sketches Relative to the Early Settlement and Successive Improvement of the Country.

Online

[edit]- "Research Vessel Prince Madog". Bangor University. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "The Previous Research Vessel - General Information". Bangor University. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Barone, Robert W. "Madoc and John Dee: Welsh Myth and Elizabethan Imperialism". Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- "Alabama backs Madoc plaque return". BBC. 7 May 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- "Call for US Madoc's plaque return". BBC. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- "Porthmadog". What's in a Name. BBC. 3 April 2013. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Pierce, Thomas Jones (1959). "Owain Gwynedd (c. 1100–1070), King of Gwynedd". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Lloyd, John Edward (1959). "DAFYDD ab OWAIN GWYNEDD (died 1203), king of Gwynedd". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- "Indiana Legend Says Welsh Settlers Arrived in the 12th Century". latimes.com. Los Angeles Times. 3 September 1989. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- "Tremadog". snowdoniaguide.com. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- "About Porthmadog". whr.co.uk. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- "Bailey Mine, Madoc Township". mindcat.org. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- "Why developer has built eye-catching feature outside some of Wales's most expensive apartments". dailypost.co.uk. 7 October 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- Curran, Kelly (8 January 2008). "The Madoc legend lives in Southern Indiana: Documentary makers hope to bring pictures to author's work". News and Tribune. Jeffersonville, Indiana. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- "Inside The Mystery Of The Moon-Eyed People From Cherokee Legend". allthatsinteresting.com. 9 April 2024.

- "The Moon-Eyed People of Cherokee Legend: Mysteries of the Smoky Mountains". appalachianmemories.org. 26 September 2024.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1893). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 35. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 302–303.

Further reading

[edit]- Brower, J. V (1904). Memoirs of Explorations in the Basin of the Mississippi. Memoirs of explorations in the basin of the Mississippi. Vol. 8. Saint Paul, Minnesota: McGill Warner – via babelhathitrust.org.

McGill-Warner