Negative-index metamaterial

Negative-index metamaterial or negative-index material (NIM) is a metamaterial whose refractive index for an electromagnetic wave has a negative value over some frequency range.[1]

NIMs are constructed of periodic basic parts called unit cells, which are usually significantly smaller than the wavelength of the externally applied electromagnetic radiation. The unit cells of the first experimentally investigated NIMs were constructed from circuit board material, or in other words, wires and dielectrics. In general, these artificially constructed cells are stacked or planar and configured in a particular repeated pattern to compose the individual NIM. For instance, the unit cells of the first NIMs were stacked horizontally and vertically, resulting in a pattern that was repeated and intended (see below images).

Specifications for the response of each unit cell are predetermined prior to construction and are based on the intended response of the entire, newly constructed, material. In other words, each cell is individually tuned to respond in a certain way, based on the desired output of the NIM. The aggregate response is mainly determined by each unit cell's geometry and substantially differs from the response of its constituent materials. In other words, the way the NIM responds is that of a new material, unlike the wires or metals and dielectrics it is made from. Hence, the NIM has become an effective medium. Also, in effect, this metamaterial has become an “ordered macroscopic material, synthesized from the bottom up”, and has emergent properties beyond its components.[2]

Metamaterials that exhibit a negative value for the refractive index are often referred to by any of several terminologies: left-handed media or left-handed material (LHM), backward-wave media (BW media), media with negative refractive index, double negative (DNG) metamaterials, and other similar names.[3]

Properties and characteristics

[edit]

The total array consists of 3 by 20×20 unit cells with overall dimensions of 10×100×100 millimeters.[4][5] The height of 10 millimeters measures a little more than six subdivision marks on the ruler, which is marked in inches.

Electrodynamics of media with negative indices of refraction were first studied by Russian theoretical physicist Victor Veselago from Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology in 1967.[6] The proposed left-handed or negative-index materials were theorized to exhibit optical properties opposite to those of glass, air, and other transparent media. Such materials were predicted to exhibit counterintuitive properties like bending or refracting light in unusual and unexpected ways. However, the first practical metamaterial was not constructed until 33 years later and it does support Veselago's concepts.[1][3][6][7]

Currently, negative-index metamaterials are being developed to manipulate electromagnetic radiation in new ways. For example, optical and electromagnetic properties of natural materials are often altered through chemistry. With metamaterials, optical and electromagnetic properties can be engineered by changing the geometry of its unit cells. The unit cells are materials that are ordered in geometric arrangements with dimensions that are fractions of the wavelength of the radiated electromagnetic wave. Each artificial unit responds to the radiation from the source. The collective result is the material's response to the electromagnetic wave that is broader than normal.[1][3][7]

Subsequently, transmission is altered by adjusting the shape, size, and configurations of the unit cells. This results in control over material parameters known as permittivity and magnetic permeability. These two parameters (or quantities) determine the propagation of electromagnetic waves in matter. Therefore, controlling the values of permittivity and permeability means that the refractive index can be negative or zero as well as conventionally positive. It all depends on the intended application or desired result. So, optical properties can be expanded beyond the capabilities of lenses, mirrors, and other conventional materials. Additionally, one of the effects most studied is the negative index of refraction.[1][3][6][7]

Reverse propagation

[edit]When a negative index of refraction occurs, propagation of the electromagnetic wave is reversed. Resolution below the diffraction limit becomes possible. This is known as subwavelength imaging. Transmitting a beam of light via an electromagnetically flat surface is another capability. In contrast, conventional materials are usually curved, and cannot achieve resolution below the diffraction limit. Also, reversing the electromagnetic waves in a material, in conjunction with other ordinary materials (including air) could result in minimizing losses that would normally occur.[1][3][6][7]

The reverse of the electromagnetic wave, characterized by an antiparallel phase velocity is also an indicator of negative index of refraction.[1][6]

Furthermore, negative-index materials are customized composites. In other words, materials are combined with a desired result in mind. Combinations of materials can be designed to achieve optical properties not seen in nature. The properties of the composite material stem from its lattice structure constructed from components smaller than the impinging electromagnetic wavelength separated by distances that are also smaller than the impinging electromagnetic wavelength. Likewise, by fabricating such metamaterials researchers are trying to overcome fundamental limits tied to the wavelength of light.[1][3][7] The unusual and counterintuitive properties currently have practical and commercial use manipulating electromagnetic microwaves in wireless and communication systems. Lastly, research continues in the other domains of the electromagnetic spectrum, including visible light.[7][8]

Materials

[edit]The first actual metamaterials worked in the microwave regime, or centimeter wavelengths, of the electromagnetic spectrum (about 4.3 GHz). It was constructed of split-ring resonators and conducting straight wires (as unit cells). The unit cells were sized from 7 to 10 millimeters. The unit cells were arranged in a two-dimensional (periodic) repeating pattern which produces a crystal-like geometry. Both the unit cells and the lattice spacing were smaller than the radiated electromagnetic wave. This produced the first left-handed material when both the permittivity and permeability of the material were negative. This system relies on the resonant behavior of the unit cells. Below a group of researchers develop an idea for a left-handed metamaterial that does not rely on such resonant behavior.

Research in the microwave range continues with split-ring resonators and conducting wires. Research also continues in the shorter wavelengths with this configuration of materials and the unit cell sizes are scaled down. However, at around 200 terahertz issues arise which make using the split ring resonator problematic. "Alternative materials become more suitable for the terahertz and optical regimes." At these wavelengths selection of materials and size limitations become important.[1][4][9][10] For example, in 2007 a 100 nanometer mesh wire design made of silver and woven in a repeating pattern transmitted beams at the 780 nanometer wavelength, the far end of the visible spectrum. The researchers believe this produced a negative refraction of 0.6. Nevertheless, this operates at only a single wavelength like its predecessor metamaterials in the microwave regime. Hence, the challenges are to fabricate metamaterials so that they "refract light at ever-smaller wavelengths" and to develop broad band capabilities.[11][12]

Artificial transmission-line-media

[edit]

In the metamaterial literature, medium or media refers to transmission medium or optical medium. In 2002, a group of researchers came up with the idea that in contrast to materials that depended on resonant behavior, non-resonant phenomena could surpass narrow bandwidth constraints of the wire/split-ring resonator configuration. This idea translated into a type of medium with broader bandwidth abilities, negative refraction, backward waves, and focusing beyond the diffraction limit.

They dispensed with split-ring-resonators and instead used a network of L–C loaded transmission lines. In metamaterial literature this became known as artificial transmission-line media. At that time it had the added advantage of being more compact than a unit made of wires and split ring resonators. The network was both scalable (from the megahertz to the tens of gigahertz range) and tunable. It also includes a method for focusing the wavelengths of interest.[13] By 2007 the negative refractive index transmission line was employed as a subwavelength focusing free-space flat lens. That this is a free-space lens is a significant advance. Part of prior research efforts targeted creating a lens that did not need to be embedded in a transmission line.[14]

The optical domain

[edit]Metamaterial components shrink as research explores shorter wavelengths (higher frequencies) of the electromagnetic spectrum in the infrared and visible spectrums. For example, theory and experiment have investigated smaller horseshoe shaped split ring resonators designed with lithographic techniques,[15][16] as well as paired metal nanorods or nanostrips,[17] and nanoparticles as circuits designed with lumped element models [18]

Applications

[edit]The science of negative-index materials is being matched with conventional devices that broadcast, transmit, shape, or receive electromagnetic signals that travel over cables, wires, or air. The materials, devices and systems that are involved with this work could have their properties altered or heightened. Hence, this is already happening with metamaterial antennas[19] and related devices which are commercially available. Moreover, in the wireless domain these metamaterial apparatuses continue to be researched. Other applications are also being researched. These are electromagnetic absorbers such as radar-microwave absorbers, electrically small resonators, waveguides that can go beyond the diffraction limit, phase compensators, advancements in focusing devices (e.g. microwave lens), and improved electrically small antennas.[20][21][22][23]

In the optical frequency regime developing the superlens may allow for imaging below the diffraction limit. Other potential applications for negative-index metamaterials are optical nanolithography, nanotechnology circuitry, as well as a near field superlens (Pendry, 2000) that could be useful for biomedical imaging and subwavelength photolithography.[23]

Manipulating permittivity and permeability

[edit]

To describe any electromagnetic properties of a given achiral material such as an optical lens, there are two significant parameters. These are permittivity, , and permeability, , which allow accurate prediction of light waves traveling within materials, and electromagnetic phenomena that occur at the interface between two materials.[24]

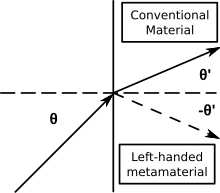

For example, refraction is an electromagnetic phenomenon which occurs at the interface between two materials. Snell's law states that the relationship between the angle of incidence of a beam of electromagnetic radiation (light) and the resulting angle of refraction rests on the refractive indices, , of the two media (materials). The refractive index of an achiral medium is given by .[25] Hence, it can be seen that the refractive index is dependent on these two parameters. Therefore, if designed or arbitrarily modified values can be inputs for and , then the behavior of propagating electromagnetic waves inside the material can be manipulated at will. This ability then allows for intentional determination of the refractive index.[24]

For example, in 1967, Victor Veselago analytically determined that light will refract in the reverse direction (negatively) at the interface between a material with negative refractive index and a material exhibiting conventional positive refractive index. This extraordinary material was realized on paper with simultaneous negative values for and , and could therefore be termed a double negative material. However, in Veselago's day a material which exhibits double negative parameters simultaneously seemed impossible because no natural materials exist which can produce this effect. Therefore, his work was ignored for three decades.[24] It was nominated for the Nobel Prize later.

In general the physical properties of natural materials cause limitations. Most dielectrics only have positive permittivities, > 0. Metals will exhibit negative permittivity, < 0 at optical frequencies, and plasmas exhibit negative permittivity values in certain frequency bands. Pendry et al. demonstrated that the plasma frequency can be made to occur in the lower microwave frequencies for metals with a material made of metal rods that replaces the bulk metal. However, in each of these cases permeability remains always positive. At microwave frequencies it is possible for negative μ to occur in some ferromagnetic materials. But the inherent drawback is they are difficult to find above terahertz frequencies. In any case, a natural material that can achieve negative values for permittivity and permeability simultaneously has not been found or discovered. Hence, all of this has led to constructing artificial composite materials known as metamaterials in order to achieve the desired results.[24]

Negative index of refraction due to chirality

[edit]In case of chiral materials, the refractive index depends not only on permittivity and permeability , but also on the chirality parameter , resulting in distinct values for left and right circularly polarized waves, given by

A negative index will occur for waves of one circular polarization if > . In this case, it is not necessary that either or both and be negative to achieve a negative index of refraction. A negative refractive index due to chirality was predicted by Pendry[26] and Tretyakov et al.,[27] and first observed simultaneously and independently by Plum et al.[28] and Zhang et al.[29] in 2009.

Physical properties never before produced in nature

[edit]Theoretical articles were published in 1996 and 1999 which showed that synthetic materials could be constructed to purposely exhibit a negative permittivity and permeability.[note 1]

These papers, along with Veselago's 1967 theoretical analysis of the properties of negative-index materials, provided the background to fabricate a metamaterial with negative effective permittivity and permeability.[30][31][32] See below.

A metamaterial developed to exhibit negative-index behavior is typically formed from individual components. Each component responds differently and independently to a radiated electromagnetic wave as it travels through the material. Since these components are smaller than the radiated wavelength it is understood that a macroscopic view includes an effective value for both permittivity and permeability.[30]

Composite material

[edit]In the year 2000, David R. Smith's team of UCSD researchers produced a new class of composite materials by depositing a structure onto a circuit-board substrate consisting of a series of thin copper split-rings and ordinary wire segments strung parallel to the rings. This material exhibited unusual physical properties that had never been observed in nature. These materials obey the laws of physics, but behave differently from normal materials. In essence these negative-index metamaterials were noted for having the ability to reverse many of the physical properties that govern the behavior of ordinary optical materials. One of those unusual properties is the ability to reverse, for the first time, Snell's law of refraction. Until the demonstration of negative refractive index for microwaves by the UCSD team, the material had been unavailable. Advances during the 1990s in fabrication and computation abilities allowed these first metamaterials to be constructed. Thus, the "new" metamaterial was tested for the effects described by Victor Veselago 30 years earlier. Studies of this experiment, which followed shortly thereafter, announced that other effects had occurred.[5][30][31][33]

With antiferromagnets and certain types of insulating ferromagnets, effective negative magnetic permeability is achievable when polariton resonance exists. To achieve a negative index of refraction, however, permittivity with negative values must occur within the same frequency range. The artificially fabricated split-ring resonator is a design that accomplishes this, along with the promise of dampening high losses. With this first introduction of the metamaterial, it appears that the losses incurred were smaller than antiferromagnetic, or ferromagnetic materials.[5]

When first demonstrated in 2000, the composite material (NIM) was limited to transmitting microwave radiation at frequencies of 4 to 7 gigahertz (4.28–7.49 cm wavelengths). This range is between the frequency of household microwave ovens (~2.45 GHz, 12.23 cm) and military radars (~10 GHz, 3 cm). At demonstrated frequencies, pulses of electromagnetic radiation moving through the material in one direction are composed of constituent waves moving in the opposite direction.[5][33][34]

The metamaterial was constructed as a periodic array of copper split ring and wire conducting elements deposited onto a circuit-board substrate. The design was such that the cells, and the lattice spacing between the cells, were much smaller than the radiated electromagnetic wavelength. Hence, it behaves as an effective medium. The material has become notable because its range of (effective) permittivity εeff and permeability μeff values have exceeded those found in any ordinary material. Furthermore, the characteristic of negative (effective) permeability evinced by this medium is particularly notable, because it has not been found in ordinary materials. In addition, the negative values for the magnetic component is directly related to its left-handed nomenclature, and properties (discussed in a section below). The split-ring resonator (SRR), based on the prior 1999 theoretical article, is the tool employed to achieve negative permeability. This first composite metamaterial is then composed of split-ring resonators and electrical conducting posts.[5]

Initially, these materials were only demonstrated at wavelengths longer than those in the visible spectrum. In addition, early NIMs were fabricated from opaque materials and usually made of non-magnetic constituents. As an illustration, however, if these materials are constructed at visible frequencies, and a flashlight is shone onto the resulting NIM slab, the material should focus the light at a point on the other side. This is not possible with a sheet of ordinary opaque material.[1][5][33] In 2007, the NIST in collaboration with the Atwater Lab at Caltech created the first NIM active at optical frequencies. More recently (as of 2008[update]), layered "fishnet" NIM materials made of silicon and silver wires have been integrated into optical fibers to create active optical elements.[35][36][37]

Simultaneous negative permittivity and permeability

[edit]Negative permittivity εeff < 0 had already been discovered and realized in metals for frequencies all the way up to the plasma frequency, before the first metamaterial. There are two requirements to achieve a negative value for refraction. First, is to fabricate a material which can produce negative permeability μeff < 0. Second, negative values for both permittivity and permeability must occur simultaneously over a common range of frequencies.[1][30]

Therefore, for the first metamaterial, the nuts and bolts are one split-ring resonator electromagnetically combined with one (electric) conducting post. These are designed to resonate at designated frequencies to achieve the desired values. Looking at the make-up of the split ring, the associated magnetic field pattern from the SRR is dipolar. This dipolar behavior is notable because this means it mimics nature's atom, but on a much larger scale, such as in this case at 2.5 millimeters. Atoms exist on the scale of picometers.

The splits in the rings create a dynamic where the SRR unit cell can be made resonant at radiated wavelengths much larger than the diameter of the rings. If the rings were closed, a half wavelength boundary would be electromagnetically imposed as a requirement for resonance.[5]

The split in the second ring is oriented opposite to the split in the first ring. It is there to generate a large capacitance, which occurs in the small gap. This capacitance substantially decreases the resonant frequency while concentrating the electric field. The individual SRR depicted on the right had a resonant frequency of 4.845 GHz, and the resonance curve, inset in the graph, is also shown. The radiative losses from absorption and reflection are noted to be small, because the unit dimensions are much smaller than the free space, radiated wavelength.[5]

When these units or cells are combined into a periodic arrangement, the magnetic coupling between the resonators is strengthened, and a strong magnetic coupling occurs. Properties unique in comparison to ordinary or conventional materials begin to emerge. For one thing, this periodic strong coupling creates a material, which now has an effective magnetic permeability μeff in response to the radiated-incident magnetic field.[5]

Composite material passband

[edit]Graphing the general dispersion curve, a region of propagation occurs from zero up to a lower band edge, followed by a gap, and then an upper passband. The presence of a 400 MHz gap between 4.2 GHz and 4.6 GHz implies a band of frequencies where μeff < 0 occurs.

(Please see the image in the previous section)

Furthermore, when wires are added symmetrically between the split rings, a passband occurs within the previously forbidden band of the split ring dispersion curves. That this passband occurs within a previously forbidden region indicates that the negative εeff for this region has combined with the negative μeff to allow propagation, which fits with theoretical predictions. Mathematically, the dispersion relation leads to a band with negative group velocity everywhere, and a bandwidth that is independent of the plasma frequency, within the stated conditions.[5]

Mathematical modeling and experiment have both shown that periodically arrayed conducting elements (non-magnetic by nature) respond predominantly to the magnetic component of incident electromagnetic fields. The result is an effective medium and negative μeff over a band of frequencies. The permeability was verified to be the region of the forbidden band, where the gap in propagation occurred – from a finite section of material. This was combined with a negative permittivity material, εeff < 0, to form a “left-handed” medium, which formed a propagation band with negative group velocity where previously there was only attenuation. This validated predictions. In addition, a later work determined that this first metamaterial had a range of frequencies over which the refractive index was predicted to be negative for one direction of propagation (see ref #[1]). Other predicted electrodynamic effects were to be investigated in other research.[5]

Describing a left-handed material

[edit]

From the conclusions in the above section a left-handed material (LHM) can be defined. It is a material which exhibits simultaneous negative values for permittivity, ε, and permeability, μ, in an overlapping frequency region. Since the values are derived from the effects of the composite medium system as a whole, these are defined as effective permittivity, εeff, and effective permeability, μeff. Real values are then derived to denote the value of negative index of refraction, and wave vectors. This means that in practice losses will occur for a given medium used to transmit electromagnetic radiation such as microwave, or infrared frequencies, or visible light – for example. In this instance, real values describe either the amplitude or the intensity of a transmitted wave relative to an incident wave, while ignoring the negligible loss values.[4][5]

Isotropic negative index in two dimensions

[edit]In the above sections first fabricated metamaterial was constructed with resonating elements, which exhibited one direction of incidence and polarization. In other words, this structure exhibited left-handed propagation in one dimension. This was discussed in relation to Veselago's seminal work 33 years earlier (1967). He predicted that intrinsic to a material, which manifests negative values of effective permittivity and permeability, are several types of reversed physics phenomena. Hence, there was then a critical need for a higher-dimensional LHMs to confirm Veselago's theory, as expected. The confirmation would include reversal of Snell's law (index of refraction), along with other reversed phenomena.

In the beginning of 2001 the existence of a higher-dimensional structure was reported. It was two-dimensional and demonstrated by both experiment and numerical confirmation. It was an LHM, a composite constructed of wire strips mounted behind the split-ring resonators (SRRs) in a periodic configuration. It was created for the express purpose of being suitable for further experiments to produce the effects predicted by Veselago.[4]

Experimental verification of a negative index of refraction

[edit]

A theoretical work published in 1967 by Soviet physicist Victor Veselago showed that a refractive index with negative values is possible and that this does not violate the laws of physics. As discussed previously (above), the first metamaterial had a range of frequencies over which the refractive index was predicted to be negative for one direction of propagation. It was reported in May 2000.[1][6][38]

In 2001, a team of researchers constructed a prism composed of metamaterials (negative-index metamaterials) to experimentally test for negative refractive index. The experiment used a waveguide to help transmit the proper frequency and isolate the material. This test achieved its goal because it successfully verified a negative index of refraction.[1][6][39][40][41][42][43]

The experimental demonstration of negative refractive index was followed by another demonstration, in 2003, of a reversal of Snell's law, or reversed refraction. However, in this experiment negative index of refraction material is in free space from 12.6 to 13.2 GHz. Although the radiated frequency range is about the same, a notable distinction is this experiment is conducted in free space rather than employing waveguides.[44]

Furthering the authenticity of negative refraction, the power flow of a wave transmitted through a dispersive left-handed material was calculated and compared to a dispersive right-handed material. The transmission of an incident field, composed of many frequencies, from an isotropic nondispersive material into an isotropic dispersive media is employed. The direction of power flow for both nondispersive and dispersive media is determined by the time-averaged Poynting vector. Negative refraction was shown to be possible for multiple frequency signals by explicit calculation of the Poynting vector in the LHM.[45]

Fundamental electromagnetic properties of the NIM

[edit]In a slab of conventional material with an ordinary refractive index – a right-handed material (RHM) – the wave front is transmitted away from the source. In a NIM the wavefront travels toward the source. However, the magnitude and direction of the flow of energy essentially remains the same in both the ordinary material and the NIM. Since the flow of energy remains the same in both materials (media), the impedance of the NIM matches the RHM. Hence, the sign of the intrinsic impedance is still positive in a NIM.[46][47]

Light incident on a left-handed material, or NIM, will bend to the same side as the incident beam, and for Snell's law to hold, the refraction angle should be negative. In a passive metamaterial medium this determines a negative real and imaginary part of the refractive index.[3][46][47]

Negative refractive index in left-handed materials

[edit]

In 1968 Victor Veselago's paper showed that the opposite directions of EM plane waves and the flow of energy was derived from the individual Maxwell curl equations. In ordinary optical materials, the curl equation for the electric field show a "right hand rule" for the directions of the electric field E, the magnetic induction B, and wave propagation, which goes in the direction of wave vector k. However, the direction of energy flow formed by E × H is right-handed only when permeability is greater than zero. This means that when permeability is less than zero, e.g. negative, wave propagation is reversed (determined by k), and contrary to the direction of energy flow. Furthermore, the relations of vectors E, H, and k form a "left-handed" system – and it was Veselago who coined the term "left-handed" (LH) material, which is in wide use today (2011). He contended that an LH material has a negative refractive index and relied on the steady-state solutions of Maxwell's equations as a center for his argument.[48]

After a 30-year void, when LH materials were finally demonstrated, it could be said that the designation of negative refractive index is unique to LH systems; even when compared to photonic crystals. Photonic crystals, like many other known systems, can exhibit unusual propagation behavior such as reversal of phase and group velocities. But, negative refraction does not occur in these systems, and not yet realistically in photonic crystals.[48][49][50]

Negative refraction at optical frequencies

[edit]The negative refractive index in the optical range was first demonstrated in 2005 by Shalaev et al. (at the telecom wavelength λ = 1.5 μm)[17] and by Brueck et al. (at λ = 2 μm) at nearly the same time.[51]

In 2006, a Caltech team led by Lezec, Dionne, and Atwater achieved negative refraction in the visible spectral regime.[52][53][54]

Reversed Cherenkov radiation

[edit]Besides reversed values for the index of refraction, Veselago predicted the occurrence of reversed Cherenkov radiation in a left-handed medium. Whereas ordinary Cherenkov radiation is emitted in a cone around the direction in which a charged particle is travelling through the medium, reversed Cherenkov radiation is emitted in a cone around the opposite direction. Reversed Cherenkov radiation was first experimentally demonstrated indirectly in 2009, using a phased electromagnetic dipole array to model a moving charged particle.[55][56] Reversed Cherenkov radiation emitted by actual charged particles was first observed in 2017.[57]

Other optics with NIMs

[edit]Theoretical work, along with numerical simulations, began in the early 2000s on the abilities of DNG slabs for subwavelength focusing. The research began with Pendry's proposed "Perfect lens." Several research investigations that followed Pendry's concluded that the "Perfect lens" was possible in theory but impractical. One direction in subwavelength focusing proceeded with the use of negative-index metamaterials, but based on the enhancements for imaging with surface plasmons. In another direction researchers explored paraxial approximations of NIM slabs.[3]

Implications of negative refractive materials

[edit]The existence of negative refractive materials can result in a change in electrodynamic calculations for the case of permeability μ = 1 . A change from a conventional refractive index to a negative value gives incorrect results for conventional calculations, because some properties and effects have been altered. When permeability μ has values other than 1 this affects Snell's law, the Doppler effect, the Cherenkov radiation, Fresnel's equations, and Fermat's principle.[10]

The refractive index is basic to the science of optics. Shifting the refractive index to a negative value may be a cause to revisit or reconsider the interpretation of some norms, or basic laws.[23]

US patent on left-handed composite media

[edit]The first US patent for a fabricated metamaterial, titled "Left handed composite media" by David R. Smith, Sheldon Schultz, Norman Kroll and Richard A. Shelby, was issued in 2004. The invention achieves simultaneous negative permittivity and permeability over a common band of frequencies. The material can integrate media which is already composite or continuous, but which will produce negative permittivity and permeability within the same spectrum of frequencies. Different types of continuous or composite may be deemed appropriate when combined for the desired effect. However, the inclusion of a periodic array of conducting elements is preferred. The array scatters electromagnetic radiation at wavelengths longer than the size of the element and lattice spacing. The array is then viewed as an effective medium.[58]

See also

[edit]- History of metamaterials

- Superlens

- Metamaterial cloaking

- Photonic metamaterials

- Metamaterial antenna

- Nonlinear metamaterials

- Photonic crystal

- Seismic metamaterials

- Split-ring resonator

- Acoustic metamaterials

- Metamaterial absorber

- Metamaterial

- Plasmonic metamaterials

- Terahertz metamaterials

- Tunable metamaterials

- Transformation optics

- Theories of cloaking

- Academic journals

- Metamaterials books

Notes

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Government. -NIST

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Government. -NIST

- ^ Negative permitivitty was explored in group of research papers which included:

- Pendry, J.B.; et al. (1996). "Extremely Low Frequency Plasmons in Metallic Microstructures". Phys. Rev. Lett. 76 (25): 4773–4776. Bibcode:1996PhRvL..76.4773P. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.76.4773. PMID 10061377. S2CID 35826875.

Effective permeability with large positive and negative values was explored in the following research:- Pendry, J.B.; Holden, A.J.; Robbins, D.J.; Stewart, W.J (1999). "Magnetism from conductors and enhanced nonlinear phenomena" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques. 47 (11): 2075–2084. Bibcode:1999ITMTT..47.2075P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.564.7060. doi:10.1109/22.798002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- Cai, W.; Chettiar, U. K.; Yuan, H.-K.; de Silva, V. C.; Kildishev, A. V.; Drachev, V. P.; Shalaev, V. M. (2007). "Metamagnetics with rainbow colors" (PDF). Optics Express. 15 (6): 3333–3341. Bibcode:2007OExpr..15.3333C. doi:10.1364/OE.15.003333. PMID 19532574.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Shelby, R. A.; Smith D.R; Shultz S. (2001). "Experimental Verification of a Negative Index of Refraction". Science. 292 (5514): 77–79. Bibcode:2001Sci...292...77S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.119.1617. doi:10.1126/science.1058847. PMID 11292865. S2CID 9321456.

- ^ Sihvola, A. (2002) "Electromagnetic Emergence in Metamaterials: Deconstruction of terminology of complex media" Archived 2012-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 3–18 in Advances in Electromagnetics of Complex Media and Metamaterials. Zouhdi, Saïd; Sihvola, Ari and Arsalane, Mohamed (eds.). Kluwer Academic. ISBN 978-94-007-1067-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h In the literature, most widely used designations are "double negative" and "left-handed". Engheta, N.; Ziolkowski, R. W. (2006). Metamaterials: Physics and Engineering Explorations. Wiley & Sons. Chapter 1. ISBN 978-0-471-76102-0.

- ^ a b c d Shelby, R. A.; Smith, D. R.; Shultz, S.; Nemat-Nasser, S. C. (2001). "Microwave transmission through a two-dimensional, isotropic, left-handed metamaterial" (PDF). Applied Physics Letters. 78 (4): 489. Bibcode:2001ApPhL..78..489S. doi:10.1063/1.1343489. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Smith, D. R.; Padilla, Willie; Vier, D.; Nemat-Nasser, S.; Schultz, S. (2000). "Composite Medium with Simultaneously Negative Permeability and Permittivity". Physical Review Letters. 84 (18): 4184–7. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..84.4184S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.4184. PMID 10990641.

- ^ a b c d e f g Veselago, V. G. (1968). "The electrodynamics of substances with simultaneously negative values of ε and μ". Soviet Physics Uspekhi. 10 (4): 509–514. Bibcode:1968SvPhU..10..509V. doi:10.1070/PU1968v010n04ABEH003699.

- ^ a b c d e f "Three-Dimensional Plasmonic Metamaterials". Plasmonic metamaterial research. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- ^ Chevalier, C. T.; Wilson, J. D. (November 2004). "Frequency Bandwidth Optimization of Left-Handed Metamaterial" (PDF). Glenn Research Center. NASA/TM—2004-213403. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ^ Boltasseva, A.; Shalaev, V. (2008). "Fabrication of optical negative-index metamaterials: Recent advances and outlook" (PDF). Metamaterials. 2 (1): 1–17. Bibcode:2008MetaM...2....1B. doi:10.1016/j.metmat.2008.03.004.

- ^ a b Veselago, Viktor G (2003). "Electrodynamics of materials with negative index of refraction". Physics-Uspekhi. 46 (7): 764. Bibcode:2003PhyU...46..764V. doi:10.1070/PU2003v046n07ABEH001614. S2CID 250862458.. Reprinted in Lim Hock; Ong Chong Kim; Serguei Matitsine (7–12 December 2003). Electromagnetic Materials. Proceedings of the Symposium F ((ICMAT 2003) ed.). SUNTEC, Singapore: World Scientific. pp. 115–122. ISBN 978-981-238-372-3.

- ^ "Caught in the "Net" Ames material negatively refracts visible light". DOE Pulse. US Department of Energy. 10 September 2007. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ^ Gibson, K. (2007). "A Visible Improvement" (PDF). Ames Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 17, 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ^ Eleftheriades, G.V.; Iyer, A.K.; Kremer, P.C. (2002). "Planar negative refractive index media using periodically L-C loaded transmission lines" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques. 50 (12): 2702. Bibcode:2002ITMTT..50.2702E. doi:10.1109/TMTT.2002.805197.

- ^ Iyer, A. K.; Eleftheriades, G. V. (2007). "A Multilayer Negative-Refractive-Index Transmission-Line (NRI-TL) Metamaterial Free-Space Lens at X-Band" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation. 55 (10): 2746. Bibcode:2007ITAP...55.2746I. doi:10.1109/TAP.2007.905924. S2CID 21922234. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-08. Retrieved 2012-08-09.

- ^ Soukoulis, C. M.; Kafesaki, M.; Economou, E. N. (2006). "Negative-Index Materials: New Frontiers in Optics" (PDF). Advanced Materials. 18 (15): 1944 and 1947. Bibcode:2006AdM....18.1941S. doi:10.1002/adma.200600106. S2CID 54507609.

- ^ Linden, S.; Enkrich, C.; Wegener, M.; Zhou, J.; Koschny, T.; Soukoulis, C. M. (2004). "Magnetic Response of Metamaterials at 100 Terahertz". Science. 306 (5700): 1351–1353. Bibcode:2004Sci...306.1351L. doi:10.1126/science.1105371. PMID 15550664. S2CID 23557190.

- ^ a b Shalaev, V. M.; Cai, W.; Chettiar, U. K.; Yuan, H.-K.; Sarychev, A. K.; Drachev, V. P.; Kildishev, A. V. (2005). "Negative index of refraction in optical metamaterials" (PDF). Optics Letters. 30 (24): 3356–8. arXiv:physics/0504091. Bibcode:2005OptL...30.3356S. doi:10.1364/OL.30.003356. PMID 16389830. S2CID 14917741.

- ^ Engheta, N. (2007). "Circuits with Light at Nanoscales: Optical Nanocircuits Inspired by Metamaterials" (PDF). Science. 317 (5845): 1698–1702. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1698E. doi:10.1126/science.1133268. PMID 17885123. S2CID 1572047. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 22, 2012. of this research by Nader Engheta (PDF format).

- ^ Slyusar V.I. (2009) "Metamaterials on antenna solutions". 7th International Conference on Antenna Theory and Techniques ICATT’09, Lviv, Ukraine, October 6–9, pp. 19–24. Archived 2021-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Engheta, N.; Ziolkowski, R. W. (2005). "A positive future for double-negative metamaterials" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques. 53 (4): 1535. Bibcode:2005ITMTT..53.1535E. doi:10.1109/TMTT.2005.845188. S2CID 15293380.

- ^ Beruete, M.; Navarro-Cía, M.; Sorolla, M.; Campillo, I. (2008). "Planoconcave lens by negative refraction of stacked subwavelength hole arrays". Optics Express. 16 (13): 9677–9683. Bibcode:2008OExpr..16.9677B. doi:10.1364/OE.16.009677. hdl:2454/31097. PMID 18575535.

- ^ Alu, A.; Engheta, N. (2004). "Guided Modes in a Waveguide Filled with a Pair of Single-Negative (SNG), Double-Negative (DNG), and/or Double-Positive (DPS) Layers". IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques. 52 (1): 199. Bibcode:2004ITMTT..52..199A. doi:10.1109/TMTT.2003.821274. S2CID 234001.

- ^ a b c Shalaev, V. M. (2007). "Optical negative-index metamaterials" (PDF). Nature Photonics. 1 (1): 41. Bibcode:2007NaPho...1...41S. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2006.49. S2CID 170678.

- ^ a b c d Liu, H.; Liu, Y. M.; Li, T.; Wang, S. M.; Zhu, S. N.; Zhang, X. (2009). "Coupled magnetic plasmons in metamaterials" (PDF). Physica Status Solidi B. 246 (7): 1397–1406. arXiv:0907.4208. Bibcode:2009PSSBR.246.1397L. doi:10.1002/pssb.200844414. S2CID 16415502. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2010.

- ^ Ulaby, Fawwaz T.; Ravaioli, Umberto. Fundamentals of Applied Electromagnetics (7th ed.). p. 363.

- ^ Pendry, J. B. (2004). "A Chiral Route to Negative Refraction". Science. 306 (5700): 1353–5. Bibcode:2004Sci...306.1353P. doi:10.1126/science.1104467. PMID 15550665. S2CID 13485411.

- ^ Tretyakov, S.; Nefedov, I.; Shivola, A.; Maslovski, S.; Simovski, C. (2003). "Waves and Energy in Chiral Nihility". Journal of Electromagnetic Waves and Applications. 17 (5): 695. arXiv:cond-mat/0211012. Bibcode:2003JEWA...17..695T. doi:10.1163/156939303322226356. S2CID 119507930.

- ^ Plum, E.; Zhou, J.; Dong, J.; Fedotov, V. A.; Koschny, T.; Soukoulis, C. M.; Zheludev, N. I. (2009). "Metamaterial with negative index due to chirality" (PDF). Physical Review B. 79 (3): 035407. arXiv:0806.0823. Bibcode:2009PhRvB..79c5407P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.79.035407. S2CID 119259753.

- ^ Zhang, S.; Park, Y.-S.; Li, J.; Lu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X. (2009). "Negative Refractive Index in Chiral Metamaterials". Physical Review Letters. 102 (2): 023901. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102b3901Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.023901. PMID 19257274.

- ^ a b c d Padilla, W.J.; Smith, D. R.; Basov, D. N. (2006). "Spectroscopy of metamaterials from infrared to optical frequencies" (PDF). Journal of the Optical Society of America B. 23 (3): 404–414. Bibcode:2006JOSAB..23..404P. doi:10.1364/JOSAB.23.000404. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-06-04.

- ^ a b "Physicists invent "left-handed" material". Physicsworld.org. Institute of Physics. 2000-03-24. p. 01. Archived from the original on 2010-01-14. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ^ Shelby, R. A.; Smith, D. R.; Schultz, S. (2001). "Experimental verification of a negative index of refraction". Science. 292 (5514): 77–79. Bibcode:2001Sci...292...77S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.119.1617. doi:10.1126/science.1058847. JSTOR 3082888. PMID 11292865. S2CID 9321456.

- ^ a b c McDonald, Kim (2000-03-21). "UCSD Physicists Develop a New Class of Composite Material with 'Reverse' Physical Properties Never Before Seen". UCSD Science and Engineering. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- ^ Program contact: Carmen Huber (2000-03-21). "Physicist Produce Left Handed Composite Material". National Science Foundation. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- ^ Ma, Hyungjin (2011). "An Experimental Study of Light-Material Interaction at Subwavelength Scale" (PDF). PhD Dissertation. MIT. p. 48. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ Cho, D.J.; Wu, Wei; Ponizovskaya, Ekaterina; Chaturvedi, Pratik; Bratkovsky, Alexander M.; Wang, Shih-Yuan; Zhang, Xiang; Wang, Feng; Shen, Y. Ron (2009-09-28). "Ultrafast modulation of optical metamaterials". Optics Express. 17 (20): 17652–7. Bibcode:2009OExpr..1717652C. doi:10.1364/OE.17.017652. PMID 19907550. S2CID 8651163.

- ^ Chaturvedi, Pratik (2009). "Optical Metamaterials: Design, Characterization and Applications" (PDF). PhD Dissertation. MIT. p. 28. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ Pennicott, Katie (2001-04-05). "Magic material flips refractive index". Physics World. Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 2010-01-13. Retrieved 2010-02-12.

- ^ Bill Casselman (2009). "The Law of Refraction". University of British Columbia, Canada, Department of Mathematics. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ^ Taylor, L.S. (2009). "An Anecdotal History of Optics from Aristophanes to Zernike". University of Maryland; Electrical Engineering Department. Archived from the original on 2011-03-05. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ^ Ward, David W.; Nelson, Keith A; Webb, Kevin J (2005). "On the physical origins of the negative index of refraction". New Journal of Physics. 7 (213): 213. arXiv:physics/0409083. Bibcode:2005NJPh....7..213W. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/7/1/213. S2CID 119434811.

- ^ Pendry, J.B.; Holden, A.J.; Robbins, D.J.; Stewart, W.J (1999). "Magnetism from conductors and enhanced nonlinear phenomena" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques. 47 (11): 2075–2084. Bibcode:1999ITMTT..47.2075P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.564.7060. doi:10.1109/22.798002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ^ "Radar types, principles, bands, hardware". Weather Edge Inc. 2000. Archived from the original on 2012-07-17. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- ^ Parazzoli, C.G.; et al. (2003-03-11). "Experimental Verification and Simulation of Negative Index of Refraction Using Snell's Law" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 90 (10): 107401 (2003) [4 pages]. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90j7401P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.107401. PMID 12689029. Archived from the original (PDF download available to the public.) on July 19, 2011.

- ^ Pacheco, J.; Grzegorczyk, T.; Wu, B.-I.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, J. (2002-12-02). "Power Propagation in Homogeneous Isotropic Frequency-Dispersive Left-Handed Media" (PDF). Phys. Rev. Lett. 89 (25): 257401 (2002) [4 pages]. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..89y7401P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.257401. PMID 12484915. Archived from the original (PDF download is available to the public.) on May 24, 2005. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ a b Caloz, C.; et al. (2001-12-01). "Full-wave verification of the fundamental properties of left-handed materials in waveguide configurations" (PDF). Journal of Applied Physics. 90 (11): 5483. Bibcode:2001JAP....90.5483C. doi:10.1063/1.1408261. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-16. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ^ a b Ziolkowski, Richard W; Ehud Heyman (2001-10-30). "Wave propagation in media having negative permittivity and permeability" (PDF). Physical Review E. 64 (5): 056625. Bibcode:2001PhRvE..64e6625Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.64.056625. PMID 11736134. S2CID 38798156. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2010. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- ^ a b Smith, David R.and; Norman Kroll (2000-10-02). "Negative Refractive Index in Left-Handed Materials" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 85 (14): 2933–2936. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.2933S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.2933. PMID 11005971. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2011. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ Srivastava, R.; et al. (2008). "Negative refraction by Photonic Crystal" (PDF). Progress in Electromagnetics Research B. 2: 15–26. doi:10.2528/PIERB08042302. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ Abo-Shaeer, Jamil R. (July 2010). "Negative-Index Materials". DARPA – Defense Science Offices (DSO). Archived from the original (Public Domain – Information presented on the DARPA Web Information Service is considered public information and may be distributed or copied.) on 2010-12-24. Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- ^ Zhang, Shuang; Fan, Wenjun; Panoiu, N. C.; Malloy, K. J.; Osgood, R. M.; Brueck, S. R. J. (2005). "Experimental Demonstration of Near-Infrared Negative-Index Metamaterials" (PDF). Phys. Rev. Lett. 95 (13): 137404. arXiv:physics/0504208. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..95m7404Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.137404. PMID 16197179. S2CID 15246675.

- ^ Caltech Media Relations. Negative Refraction of Visible Light Demonstrated; Could Lead to Cloaking Devices Archived June 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. March 22, 2007. accessdate – 2010-05-05

- ^ PhysOrg.com (April 22, 2010). "Novel negative-index metamaterial that responds to visible light designed" (Web page). Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ Dillow, Clay (April 23, 2010). "New Metamaterial First to Bend Light in the Visible Spectrum" (Web page). Popular Science. Retrieved 2010-05-05.[dead link]

- ^ Xi, Sheng; et al. (2009-11-02). "Experimental Verification of Reversed Cherenkov Radiation in Left-Handed Metamaterial". Phys. Rev. Lett. 103 (19): 194801 (2009). Bibcode:2009PhRvL.103s4801X. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.194801. hdl:1721.1/52503. PMID 20365927. S2CID 1501102.

- ^ Zhang, Shuang; Xiang Zhang (2009-11-02). "Flipping a photonic shock wave". Physics. 02 (91): 03. Bibcode:2009PhyOJ...2...91Z. doi:10.1103/Physics.2.91.

- ^ Duan, Zhaoyun; Tang, Xianfeng; Wang, Zhanliang; Zhang, Yabin; Chen, Xiaodong; Chen, Min; Gong, Yubin (23 March 2017). "Observation of the reversed Cherenkov radiation". Nature Communications. 8 14901. doi:10.1038/ncomms14901. PMC 5376646. PMID 28332487.

- ^ Smith, David; Schultz, Sheldon; Kroll, Norman; Shelby, Richard A. "Left handed composite media" U.S. patent 6,791,432 Publication date 2001-03-16, Issue date 2004-03-14.

Further reading

[edit]- S. Anantha Ramakrishna; Tomasz M. Grzegorczyk (2008). Physics and Applications of Negative Refractive Index Materials (PDF). CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9781420068764.ch1 (inactive 2024-11-12). ISBN 978-1-4200-6875-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Ramakrishna, S Anantha (2005). "Physics of negative refractive index materials". Reports on Progress in Physics. 68 (2): 449. Bibcode:2005RPPh...68..449R. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/68/2/R06. S2CID 250829241.

- Pendry, J.; Holden, A.; Stewart, W.; Youngs, I. (1996). "Extremely Low Frequency Plasmons in Metallic Mesostructures" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 76 (25): 4773–4776. Bibcode:1996PhRvL..76.4773P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.4773. PMID 10061377. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- Pendry, J B; Holden, A J; Robbins, D J; Stewart, W J (1998). "Low frequency plasmons in thin-wire structures" (PDF). Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 10 (22): 4785–4809. Bibcode:1998JPCM...10.4785P. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/10/22/007. S2CID 250891354. Also see the Preprint-author's copy.

- Padilla, Willie J.; Basov, Dimitri N.; Smith, David R. (2006). "Negative refractive index metamaterials". Materials Today. 9 (7–8): 28. doi:10.1016/S1369-7021(06)71573-5.

- Bayindir, Mehmet; Aydin, K.; Ozbay, E.; Markoš, P.; Soukoulis, C. M. (2002-07-01). "Transmission properties of composite metamaterials in free space" (PDF). Applied Physics Letters. 81 (1): 120. Bibcode:2002ApPhL..81..120B. doi:10.1063/1.1492009. hdl:11693/24684.[dead link]

External links

[edit]- Manipulating the Near Field with Metamaterials Slide show, with audio available, by Dr. John Pendry, Imperial College, London

- Laszlo Solymar; Ekaterina Shamonina (2009-03-15). Waves in Metamaterials. Oxford University Press, USA. March 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-921533-1.

- "Illustrating the Law of Refraction".

- Young, Andrew T. (1999–2009). "An Introduction to Mirages". SDSU San Diego, CA. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- Garrett, C.; et al. (1969-09-25). "Light pulse and anamolous dispersion". Phys. Rev. A. 1 (2): 305–313. Bibcode:1970PhRvA...1..305G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.1.305.

- List of science website news stories on Left Handed Materials

- Caloz, Christophe (March 2009). "Perspectives on EM metamaterials". Materials Today. 12 (3): 12–20. doi:10.1016/S1369-7021(09)70071-9.