Retinal detachment

| Retinal detachment | |

|---|---|

| |

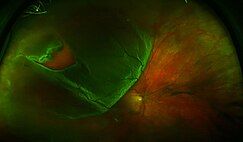

| Cross section of retinal detachment | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

Retinal detachment is a condition where the retina pulls away from the tissue underneath it.[1][2][3] It may start in a small area, but without quick treatment, it can spread across the entire retina, leading to serious vision loss and possibly blindness.[4] Retinal detachment is a medical emergency that requires surgery.[2][3]

The retina is a thin layer at the back of the eye that processes visual information and sends it to the brain.[5] When the retina detaches, common symptoms include seeing floaters, flashing lights, a dark shadow in vision, and sudden blurry vision.[1][3] The most common type of retinal detachment is rhegmatogenous, which occurs when a tear or hole in the retina lets fluid from the center of the eye get behind it, causing the retina to pull away.[6]

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is most commonly caused by posterior vitreous detachment, a condition where the gel inside the eye breaks down and pulls on the retina.[4][7] Risk factors include older age, nearsightedness (myopia), eye injury, cataract surgery, and inflammation.[7][8]

Retinal detachment is usually diagnosed through a dilated eye exam.[4] If needed, additional imaging tests can help confirm the diagnosis.[8] Treatment involves surgery to reattach the retina, such as pneumatic retinopexy, vitrectomy, or scleral buckling.[2] Prompt treatment is crucial to protect vision.[8]

Mechanism and classification

[edit]

The retina is a thin layer of tissue located at the back of the eye.[1][5] It processes visual information and transmits it to the brain.[5] Retinal detachment occurs when the retina separates from the layers underneath it.[2] This impairs its function, potentially leading to vision loss.[2][4] Retinal detachment often requires urgent medical intervention to prevent permanent vision loss.[3]

Retinal detachments are divided into three main types based on their distinct causes.[6]

- Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is caused by a tear or break in the retina.[6][9] This allows vitreous humor, the fluid that normally sits in the center of the eye, to build up behind the retina.[6][9] As a result, the retina can eventually separate from the tissues underneath it.[6][9][10] This is the most common type of retinal detachment.[6]

- Tractional retinal detachment occurs when scar tissue on the retina exerts a pulling force, leading to detachment.[6][10] This is occurs in the absence of retinal tears or breaks and is most commonly associated with abnormal blood vessel growth due to proliferative diabetic retinopathy.[6][9][10] Other causes include trauma, retinal vein occlusion, sickle cell retinopathy, and retinopathy of prematurity.[8][9][10][11]

- Exudative retinal detachment occurs when fluid accumulates beneath the retina, causing it to detach.[6][10][11] This occurs in the absence of retinal tears or breaks. Common causes include age-related macular degeneration, inflammatory diseases, ocular tumors, and injuries to the eye.[6][9][10][11]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Retinal detachment is typically painless, with symptoms often starting in the peripheral vision.[3][9][10]

Symptoms of retinal detachment, as well as posterior vitreous detachment (which often, but not always, precedes it), may include:[3][4][9][10][12]

- Floaters suddenly appearing in the field of vision or a sudden increase in the number of floaters. Floaters may resemble cobwebs, specks of dust, or shapes such as ovals or circles

- Flashes of light in vision (photopsia)

- Experiencing a "dark curtain" or shadow moving from the peripheral vision toward the central vision

- Sudden blurred vision

Rarely, a retinal detachment may be caused by atrophic retinal holes, in which case symptoms such as floaters or flashes of light may not occur.[9][10]

Causes and risk factors

[edit]Rhegmatogenous retinal detachments are most often caused by posterior vitreous detachment (PVD).[1][3] This occurs when the vitreous begins to liquefy and shrink, pulling away from the retina.[13][14] While this process is typically harmless and often presents without symptoms, it can lead to retinal holes or tears that may progress to a full retinal detachment if left untreated.[8][15]

Risk Factors Related to Posterior Vitreous Detachment

[edit]Factors that increase the likelihood of posterior vitreous detachment and therefore, retinal detachment, include:

- Age: The vitreous liquefies as a normal part of aging, increasing the risk for subsequent detachment.[9][15][16]

- Myopia (nearsightedness): Individuals with myopia have a longer axial length of the eyeball, which increases their risk of developing posterior vitreous detachment.[10][16]

- Trauma: Blunt and penetrating trauma to the eye can disrupt the vitreous, leading to posterior vitreous detachment.[7][16]

- Cataract surgery: Previous cataract surgery, particularly when associated with vitreous loss, is linked to shifts in the vitreous, increasing the risk of posterior vitreous detachment.[7][9][17]

- Inflammation: Inflammatory eye conditions, such as uveitis, are associated with an increased risk of posterior vitreous detachment.[7][9]

Other Risk Factors

[edit]Less frequently, rhegmatogenous retinal detachments can occur without PVD. Risk factors for retinal detachment that are not related to posterior vitreous detachment include:

- Family history of retinal detachment[10]

- Previous retinal detachment in the other eye[8][9][10]

- Lattice degeneration: Thinning of the retina, which increases its susceptibility to breaks or tears.[9][10][18]

- Cystic retinal tuft: A small, raised spot present on the retina from birth that increases the risk for tears and detachment.[9][10]

Diagnosis

[edit]

The gold standard for diagnosing retinal detachment is a dilated fundus examination to check the back of the eye using an indirect ophthalmoscope.[8][10][13] This often involves a technique called scleral depression, which helps provide a clear view of the entire retina.[8][10][14] A slit lamp examination of the front of the eye may also reveal small pigment particles, called Shafer's sign, which may indicate a retinal tear.[8][9][10]

If the view of the retina is not clear, imaging techniques such as ultrawide-field fundus photography, B-scan ultrasonography, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) may help to identify a detachment.[8][13][14] Fundus photography provides a detailed view of the back of the eye, potentially revealing retinal tears or breaks.[8][16] On B-scan ultrasonography, a detached retina typically appears as a membrane floating in the vitreous cavity, moving in a wave-like motion.[19] OCT can detect fluid behind the retina, involvement of the macula (the central part of the retina), and other abnormalities within the retinal layers.[8][20]

MRI and CT scans are less commonly used for the diagnosis of retinal detachment, but they may be useful in certain cases.[8][10] In an emergency department setting, bedside ultrasonography can also be used for diagnosis.[8][13][14]

Treatment

[edit]Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment typically requires prompt surgical intervention to preserve vision.[3][8][9][10] The 3 main options include pneumatic retinopexy, vitrectomy, and scleral buckle.[2] These are selected based on how the patient presents, including the number, location and size of retinal tears, surgeon preference, and cost.[8][10][21]

Pneumatic retinopexy

[edit]Pneumatic retinopexy is an office-based procedure often used for small and uncomplicated retinal detachments, particularly those involving a single tear in the superior part of the retina.[9][10] A gas bubble is injected into the vitreous cavity to push the retina back into place against the back of the eye.[2][9][22] Additionally, freezing (cryotherapy) or lasers are used to seal the retinal tears and prevent further detachment.[9][10][22] Following the procedure, patients are advised to maintain a specific head position to ensure the gas bubble remains in place over the tear and to facilitate proper healing.[8][22] Patients must also avoid air travel, high altitudes, and scuba diving until the gas bubble dissolves.[22] Over time, the gas bubble will be naturally replaced by the eye’s vitreous fluid.[2]

Vitrectomy

[edit]Vitrectomy is a surgical procedure used to treat complicated retinal detachments.[8] It is especially useful for large retinal tears or tears that are not easily visible.[8] Vitrectomy is also used for proliferative vitreoretinopathy, which is the growth of scar tissue on the retina that can occur after a retinal detachment.[8][23][24] In this technique, the vitreous gel is removed from the eye to relieve the pulling force on the retina.[8][10] Any fluid behind the retina is drained, and tears are sealed with freezing or lasers.[8][10] The removed vitreous is then replaced with either a gas bubble or silicone oil, which stabilizes the retina.[8][10][25] Patients treated with a gas bubble are advised to maintain a face-down position and refrain from air travel, high altitudes, and scuba diving.[8][10][25][26] In patients treated with silicone oil, a follow-up surgery is required to remove the oil.[8][10][26] For patients who have not previously undergone cataract surgery, vitrectomy increases the risk of developing a cataract in the treated eye.[8][10][26]

Scleral buckle surgery

[edit]Scleral buckle surgery is a procedure in which one or more silicone bands are placed around the outer layer of the eye, known as the sclera.[1][8] The procedure typically begins with freezing (cryotherapy) to seal retinal tears.[10][21] Next, the silicone band is placed to create an indentation on the sclera, applying inward pressure that helps reattach the retina to the back of the eye.[1][2][8][9] After surgery, the person is often positioned in a prone position to reduce the risk of hemorrhages by preventing blood from reaching the macula.[27] The band typically remains in place permanently unless complications occur.[8] During the procedure, subretinal fluid may also be drained, though it is sometimes left to reabsorb naturally.[8][9] This approach is often preferred for younger patients, those who have not undergone cataract surgery, those without posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), and those with retinal dialysis, a type of tear commonly caused by trauma.[8][9][14][21] Possible complications of this procedure include missed retinal breaks, improper positioning of the buckle, infection, inflammation, and double vision immediately after surgery, which typically resolves on its own.[8][9][21] Scleral buckling can also be combined with vitrectomy for specific cases.[10][14]

Prognosis

[edit]If left untreated, retinal detachment can lead to permanent vision loss.[2]

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair has a success rate of approximately 95%, meaning the retina is successfully reattached in most cases.[14] It is important for the repair to be successful the first time, as the chances of reattachment and good vision decrease with each additional surgery.[14]

Visual outcomes may vary even after successful reattachment.[3] The results for a patient’s vision depend greatly on whether the macula, the central part of the retina responsible for detailed vision, remains attached.[10][14] If the macula detaches, the risk of poor vision increases, particularly if surgery is delayed.[10][14]

Other factors that can affect the prognosis include the extent of the detachment and the timing of surgery, with earlier treatment generally leading to better outcomes.[3][16]

Common causes of failure in retinal detachment repair include missed or poorly sealed retinal breaks, new retinal breaks, and proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR).[10][14] PVR, a condition where scar tissue grows on the retina, occurs in approximately 8–10% of patients undergoing treatment for retinal detachment.[10]

Prevention

[edit]Patients at high risk for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, such as those with myopia (nearsightedness), those who have had cataract surgery, those with a previous detachment in the other eye, and those with lattice degeneration or posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), should be educated on the symptoms and warning sings of retinal detachment and seek urgent treatment if they occur.[8][16]

They should also have regular eye exams, even if they are not experiencing symptoms.[8]

Individuals with certain types of retinal tears or breaks may require treatments such as lasers or freezing (cryotherapy) to prevent detachment.[8][10]

Additionally, these patients are advised to avoid contact sports, eye trauma, and other high-risk activities, and to wear protective eyewear to reduce the risk of eye injury.[3][8]

Epidemiology

[edit]Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment affects between 5.3 and 12.6 individuals per 100,000 each year, depending on the geographic region.[14] The highest rates are seen in Europe, followed by the Western Pacific and then the Americas.[8][28] Additionally, the prevalence of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is increasing alongside the rising rates of myopia worldwide.[14]

See also

[edit]- Uveitis

- Posterior vitreous detachment

- Retinal artery occlusion

- Retinal vein occlusion

- Vitreous hemorrhage

- Optic neuritis

- Migraine with aura

- Transient ischemic attack

- Macular hole

- Age-related macular degeneration

- Diabetic retinopathy

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Detached retina (retinal detachment)". www.nhs.co.uk. NHS. 2020-12-16. Retrieved 2023-05-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Detached Retina". American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2024-10-11. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Retinal detachment". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. National Institutes of Health. 2005. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- ^ a b c d e "Retinal Detachment | National Eye Institute". www.nei.nih.gov. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ a b c "Retina". American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2020-09-08. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Types and Causes of Retinal Detachment | National Eye Institute". www.nei.nih.gov. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ a b c d e Ahmed, Faryal; Tripathy, Koushik (2024), "Posterior Vitreous Detachment", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 33085420, retrieved 2024-12-06

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Lin, Jonathan B.; Narayanan, Raja; Philippakis, Elise; Yonekawa, Yoshihiro; Apte, Rajendra S. (2024-03-14). "Retinal detachment". Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 10 (1): 18. doi:10.1038/s41572-024-00501-5. ISSN 2056-676X. PMID 38485969.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Kanski's Synopsis of Clinical Ophthalmology. Elsevier. 2023. doi:10.1016/c2013-0-19108-8. ISBN 978-0-7020-8373-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Blair, Kyle; Czyz, Craig N. (2024), "Retinal Detachment", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31855346, retrieved 2024-12-04

- ^ a b c Basic and Clinical Science Course Section 12: Retina and Vitreous. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2023–2024.

- ^ "Posterior Vitreous Detachment - Patients - The American Society of Retina Specialists". www.asrs.org. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ a b c d Walls, Ron M.; Hockberger, Robert S.; Gausche-Hill, Marianne; Rosen, Peter, eds. (2023). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-75789-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Yanoff, Myron; Duker, Jay S., eds. (2023). Ophthalmology (Sixth ed.). London New York Oxford Philadelphia St. Louis Sydney: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-79515-9.

- ^ a b "What Is a Posterior Vitreous Detachment?". American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2024-11-07. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ a b c d e f Flaxel, Christina J.; Adelman, Ron A.; Bailey, Steven T.; Fawzi, Amani; Lim, Jennifer I.; Vemulakonda, G. Atma; Ying, Gui-shuang (January 2020). "Posterior Vitreous Detachment, Retinal Breaks, and Lattice Degeneration Preferred Practice Pattern®". Ophthalmology. 127 (1): P146 – P181. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.09.027. ISSN 0161-6420. PMID 31757500.

- ^ Sadda, SriniVas R.; Wilkinson, Charles P.; Wiedemann, Peter; Schachat, Andrew P., eds. (2023). Ryan's Retina. Volume 3 / editor-in-chief SriniVas R. Sadda, MD (Professor of Ophthalmology, Doheny Eye Institute, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA) (Seventh ed.). London New York Oxford Philadelphia St Louis Sydney: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-72213-1.

- ^ "Lattice Degeneration - Patients - The American Society of Retina Specialists". www.asrs.org. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ "Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment: Features, Part 1". American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2018-12-01. Retrieved 2024-12-18.

- ^ Duker, Jay S.; Waheed, Nadia K.; Goldman, Darin; Desai, Shilpa J., eds. (2023). Atlas of Retinal OCT: Optical Coherence Tomography (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-93104-5.

- ^ a b c d Sultan, Ziyaad Nabil; Agorogiannis, Eleftherios I.; Iannetta, Danilo; Steel, David; Sandinha, Teresa (2020-10-08). "Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a review of current practice in diagnosis and management". BMJ Open Ophthalmology. 5 (1): e000474. doi:10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000474. ISSN 2397-3269. PMC 7549457. PMID 33083551.

- ^ a b c d "Surgery for Retinal Detachment | National Eye Institute". www.nei.nih.gov. Retrieved 2024-12-08.

- ^ "Complex Retinal Detachment - Patients - The American Society of Retina Specialists". www.asrs.org. Retrieved 2024-12-08.

- ^ Idrees, Sana; Sridhar, Jayanth; Kuriyan, Ajay E. (2019). "Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy: A Review". International Ophthalmology Clinics. 59 (1): 221–240. doi:10.1097/IIO.0000000000000258. ISSN 1536-9617. PMC 6310037. PMID 30585928.

- ^ a b "Vitrectomy | National Eye Institute". www.nei.nih.gov. Retrieved 2024-12-08.

- ^ a b c "What Is Vitrectomy?". American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2024-10-01. Retrieved 2024-12-08.

- ^ Fallico, Matteo; Alosi, Pietro; Reibaldi, Michele; Longo, Antonio; Bonfiglio, Vincenza; Avitabile, Teresio; Russo, Andrea (2022-01-09). "Scleral Buckling: A Review of Clinical Aspects and Current Concepts". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 11 (2): 314. doi:10.3390/jcm11020314. PMC 8778378. PMID 35054009.

- ^ Ge, Jasmine Yaowei; Teo, Zhen Ling; Chee, Miao Li; Tham, Yih-Chung; Rim, Tyler Hyungtaek; Cheng, Ching-Yu; Wong, Tien Yin; Wong, Edmund Yick Mun; Lee, Shu Yen; Cheung, Ning (2024-05-01). "International incidence and temporal trends for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Survey of Ophthalmology. 69 (3): 330–336. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2023.11.005. ISSN 0039-6257. PMID 38000699.

External links

[edit]- Retinal Detachment Resource Guide from the National Eye Institute (NEI)

- Overview of retinal detachment from eMedicine

- Retinal detachment information from WebMD