De-extinction

De-extinction (also known as resurrection biology, or species revivalism) is the process of generating an organism that either resembles or is an extinct species.[1] There are several ways to carry out the process of de-extinction. Cloning is the most widely proposed method, although genome editing and selective breeding have also been considered. Similar techniques have been applied to certain endangered species, in hopes to boost their genetic diversity. The only method of the three that would provide an animal with the same genetic identity is cloning.[2] There are benefits and drawbacks to the process of de-extinction ranging from technological advancements to ethical issues.

Methods

[edit]Cloning

[edit]

Cloning is a commonly suggested method for the potential restoration of an extinct species. It can be done by extracting the nucleus from a preserved cell from the extinct species and swapping it into an egg, without a nucleus, of that species' nearest living relative.[3] The egg can then be inserted into a host from the extinct species' nearest living relative. This method can only be used when a preserved cell is available, meaning it would be most feasible for recently extinct species.[4] Cloning has been used by scientists since the 1950s.[5] One of the most well known clones is Dolly the sheep. Dolly was born in the mid 1990s and lived normally until the abrupt midlife onset of health complications resembling premature aging, that led to her death.[5] Other known cloned animal species include domestic cats, dogs, pigs, and horses.[5]

Genome editing

[edit]Genome editing has been rapidly advancing with the help of the CRISPR/Cas systems, particularly CRISPR/Cas9. The CRISPR/Cas9 system was originally discovered as part of the bacterial immune system.[6] Viral DNA that was injected into the bacterium became incorporated into the bacterial chromosome at specific regions. These regions are called clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, otherwise known as CRISPR. Since the viral DNA is within the chromosome, it gets transcribed into RNA. Once this occurs, the Cas9 binds to the RNA. Cas9 can recognize the foreign insert and cleaves it.[6] This discovery was very crucial because now the Cas protein can be viewed as a scissor in the genome editing process.

By using cells from a closely related species to the extinct species, genome editing can play a role in the de-extinction process. Germ cells may be edited directly, so that the egg and sperm produced by the extant parent species will produce offspring of the extinct species, or somatic cells may be edited and transferred via somatic cell nuclear transfer. The result is an animal which is not completely the extinct species, but rather a hybrid of the extinct species and the closely related, non-extinct species. Because it is possible to sequence and assemble the genome of extinct organisms from highly degraded tissues, this technique enables scientists to pursue de-extinction in a wider array of species, including those for which no well-preserved remains exist.[3] However, the more degraded and old the tissue from the extinct species is, the more fragmented the resulting DNA will be, making genome assembly more challenging.

Back-breeding

[edit]Back breeding is a form of selective breeding. As opposed to breeding animals for a trait to advance the species in selective breeding, back breeding involves breeding animals for an ancestral characteristic that may not be seen throughout the species as frequently.[7] This method can recreate the traits of an extinct species, but the genome will differ from the original species.[4] Back breeding, however, is contingent on the ancestral trait of the species still being in the population in any frequency.[7] Back breeding is also a form of artificial selection by the deliberate selective breeding of domestic animals, in an attempt to achieve an animal breed with a phenotype that resembles a wild type ancestor, usually one that has gone extinct.

Iterative evolution

[edit]A natural process of de-extinction is iterative evolution. This occurs when a species becomes extinct, but then after some time a different species evolves into an almost identical creature. For example, the Aldabra rail was a flightless bird that lived on the island of Aldabra. It had evolved some time in the past from the flighted white-throated rail, but became extinct about 136,000 years ago due to an unknown event that caused sea levels to rise. About 100,000 years ago, sea levels dropped and the island reappeared, with no fauna. The white-throated rail recolonized the island, but soon evolved into a flightless species physically identical to the extinct species.[8][9]

Herbarium specimens for de-extincting plants

[edit]Not all extinct plants have herbarium specimens that contain seeds. Of those that do, there is ongoing discussion on how to coax barely alive embryos back to life.[10] See Judean date palm and tsori.

In-vitro fertilisation and artificial insemination

[edit]In-vitro fertilisation and artificial insemination are assisted reproduction technology commonly used to treat infertility in humans. However, it has usage as a viable option for de-extinction in cases of functional extinction where all remaining individuals are of the same sex, incapable of naturally reproducing, or suffer from low genetic diversity such as the northern white rhinoceros, Yangtze giant softshell turtle, Hyophorbe amaricaulis, baiji, and vaquita. [11] For example, viable embryos are created from preserved sperm from deceased males and ova from living females are implemented into a surrogate species.[12]

Advantages of de-extinction

[edit]The technologies being developed for de-extinction could lead to large advances in various fields:

- An advance in genetic technologies that are used to improve the cloning process for de-extinction could be used to prevent endangered species from becoming extinct.[13]

- By studying revived previously extinct animals, cures to diseases could be discovered.

- Revived species may support conservation initiatives by acting as "flagship species" to generate public enthusiasm and funds for conserving entire ecosystems.[14][15]

Prioritising de-extinction could lead to the improvement of current conservation strategies. Conservation measures would initially be necessary in order to reintroduce a species into the ecosystem, until the revived population can sustain itself in the wild.[16] Reintroduction of an extinct species could also help improve ecosystems that had been destroyed by human development. It may also be argued that reviving species driven to extinction by humans is an ethical obligation.[17]

Disadvantages of de-extinction

[edit]The reintroduction of extinct species could have a negative impact on extant species and their ecosystem. The extinct species' ecological niche may have been filled in its former habitat, making it an invasive species. This could lead to the extinction of other species due to competition for food or other competitive exclusion. It could lead to the extinction of prey species if they have more predators in an environment that had few predators before the reintroduction of an extinct species.[17] If a species has been extinct for a long period of time the environment they are introduced to could be wildly different from the one that they can survive in. The changes in the environment due to human development could mean that the species may not survive if reintroduced into that ecosystem.[13] A species could also become extinct again after de-extinction if the reasons for its extinction are still a threat. The woolly mammoth might be hunted by poachers just like elephants for their ivory and could go extinct again if this were to happen. Or, if a species is reintroduced into an environment with disease for which it has no immunity, the reintroduced species could be wiped out by a disease that current species can survive.

De-extinction is a very expensive process. Bringing back one species can cost millions of dollars. The money for de-extinction would most likely come from current conservation efforts. These efforts could be weakened if funding is taken from conservation and put into de-extinction. This would mean that critically endangered species would start to go extinct faster because there are no longer resources that are needed to maintain their populations.[18] Also, since cloning techniques cannot perfectly replicate a species as it existed in the wild, the reintroduction of the species may not bring about positive environmental benefits. They may not have the same role in the food chain that they did before and therefore cannot restore damaged ecosystems.[19]

Current candidate species for de-extinction

[edit]

Woolly mammoth

[edit]The existence of preserved soft tissue remains and DNA from woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) has led to the idea that the species could be recreated by scientific means. Two methods have been proposed to achieve this:

The first would be to use the cloning process;[20] however, even the most intact mammoth samples have had little usable DNA because of their conditions of preservation. There is not enough DNA intact to guide the production of an embryo.[21]

The second method would involve artificially inseminating an elephant egg cell with preserved sperm of the mammoth. The resulting offspring would be a hybrid of the mammoth and its closest living relative the Asian elephant. After several generations of cross-breeding these hybrids, an almost pure woolly mammoth could be produced. However, sperm cells of modern mammals are typically potent for up to 15 years after deep-freezing, which could hinder this method.[22] Whether the hybrid embryo would be carried through the two-year gestation is unknown; in one case, an Asian elephant and an African elephant produced a live calf named Motty, but it died of defects at less than two weeks old.[23]

In 2008, a Japanese team found usable DNA in the brains of mice that had been frozen for 16 years. They hope to use similar methods to find usable mammoth DNA.[24] In 2011, Japanese scientists announced plans to clone mammoths within six years.[25]

In March 2014, the Russian Association of Medical Anthropologists reported that blood recovered from a frozen mammoth carcass in 2013 would now provide a good opportunity for cloning the woolly mammoth.[22] Another way to create a living woolly mammoth would be to migrate genes from the mammoth genome into the genes of its closest living relative, the Asian elephant, to create hybridized animals with the notable adaptations that it had for living in a much colder environment than modern day elephants.[26] This is currently being done by a team led by Harvard geneticist George Church.[27] The team has made changes in the elephant genome with the genes that gave the woolly mammoth its cold-resistant blood, longer hair, and an extra layer of fat.[27] According to geneticist Hendrik Poinar, a revived woolly mammoth or mammoth-elephant hybrid may find suitable habitat in the tundra and taiga forest ecozones.[28]

George Church has hypothesized the positive effects of bringing back the extinct woolly mammoth would have on the environment, such as the potential for reversing some of the damage caused by global warming.[29] He and his fellow researchers predict that mammoths would eat the dead grass allowing the sun to reach the spring grass; their weight would allow them to break through dense, insulating snow in order to let cold air reach the soil; and their characteristic of felling trees would increase the absorption of sunlight.[29] In an editorial condemning de-extinction, Scientific American pointed out that the technologies involved could have secondary applications, specifically to help species on the verge of extinction regain their genetic diversity.[30]

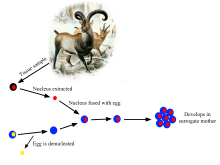

Pyrenean ibex

[edit]

The Pyrenean ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) was a subspecies of Iberian ibex that lived on the Iberian Peninsula. While it was abundant through medieval times, over-hunting in the 19th and 20th centuries led to its demise. In 1999, only a single female named Celia was left alive in Ordesa National Park. Scientists captured her, took a tissue sample from her ear, collared her, then released her back into the wild, where she lived until she was found dead in 2000, having been crushed by a fallen tree.

In 2003, scientists used the tissue sample to attempt to clone Celia and resurrect the extinct subspecies. Despite having successfully transferred nuclei from her cells into domestic goat egg cells and impregnating 208 female goats, only one came to term. The baby ibex that was born had a lung defect, and lived for only seven minutes before suffocating from being incapable of breathing oxygen. Nevertheless, her birth was seen as a triumph and is considered the first de-extinction.[31] In late 2013, scientists announced that they would again attempt to resurrect the Pyrenean ibex.[32][33]

A problem to be faced, in addition to the many challenges of reproduction of a mammal by cloning, is that only females can be produced by cloning the female individual Celia, and no males exist for those females to reproduce with. This could potentially be addressed by breeding female clones with the closely related Southeastern Spanish ibex, and gradually creating a hybrid animal that will eventually bear more resemblance to the Pyrenean ibex than the Southeastern Spanish ibex.[32]

Aurochs

[edit]

The aurochs (Bos primigenius) was widespread across Eurasia, North Africa, and the Indian subcontinent during the Pleistocene, but only the European aurochs (B. p. primigenius) survived into historical times.[34] This species is heavily featured in European cave paintings, such as Lascaux and Chauvet cave in France,[35] and was still widespread during the Roman era. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, overhunting of the aurochs by nobility caused its population to dwindle to a single population in the Jaktorów forest in Poland, where the last wild one died in 1627.[36]

However, because the aurochs is ancestral to most modern cattle breeds, it is possible for it to be brought back through selective or back breeding. The first attempt at this was by Heinz and Lutz Heck using modern cattle breeds, which resulted in the creation of Heck cattle. This breed has been introduced to nature preserves across Europe; however, it differs strongly from the aurochs in physical characteristics, and some modern attempts claim to try to create an animal that is nearly identical to the aurochs in morphology, behavior, and even genetics.[37] There are several projects that aim to create a cattle breed similar to the aurochs through selectively breeding primitive cattle breeds over a course of twenty years to create a self-sufficient bovine grazer in herds of at least 150 animals in rewilded nature areas across Europe, for example the Tauros Programme and the separate Taurus Project.[38] This organization is partnered with the organization Rewilding Europe to help revert some European natural ecosystems to their prehistoric form.[39]

A competing project to recreate the aurochs is the Uruz Project by the True Nature Foundation, which aims to recreate the aurochs by a more efficient breeding strategy using genome editing, in order to decrease the number of generations of breeding needed and the ability to quickly eliminate undesired traits from the population of aurochs-like cattle.[40] It is hoped that aurochs-like cattle will reinvigorate European nature by restoring its ecological role as a keystone species, and bring back biodiversity that disappeared following the decline of European megafauna, as well as helping to bring new economic opportunities related to European wildlife viewing.[41]

Quagga

[edit]

The quagga (Equus quagga quagga) is a subspecies of the plains zebra that was distinct in that it was striped on its face and upper torso, but its rear abdomen was a solid brown. It was native to South Africa, but was wiped out in the wild due to overhunting for sport, and the last individual died in 1883 in the Amsterdam Zoo.[42] However, since it is technically the same species as the surviving plains zebra, it has been argued that the quagga could be revived through artificial selection. The Quagga Project aims to breed a similar form of zebra by selective breeding of plains zebras.[43] This process is also known as back breeding. It also aims to release these animals onto the western Cape once an animal that fully resembles the quagga is achieved, which could have the benefit of eradicating introduced species of trees such as the Brazilian pepper tree, Tipuana tipu, Acacia saligna, bugweed, camphor tree, stone pine, cluster pine, weeping willow and Acacia mearnsii.[44]

Thylacine

[edit]

The thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger, was native to the Australian mainland, Tasmania and New Guinea. It is believed to have become extinct in the 20th century. The thylacine had become extremely rare or extinct on the Australian mainland before British settlement of the continent. The last known thylacine died at the Hobart Zoo, on September 7, 1936. He is believed to have died as the result of neglect—locked out of his sheltered sleeping quarters, he was exposed to a rare occurrence of extreme Tasmanian weather: extreme heat during the day and freezing temperatures at night.[45] Official protection of the species by the Tasmanian government was introduced on July 10, 1936, roughly 59 days before the last known specimen died in captivity.[46]

In December 2017, it was announced in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution that the full nuclear genome of the thylacine had been successfully sequenced, marking the completion of the critical first step toward de-extinction that began in 2008, with the extraction of the DNA samples from the preserved pouch specimen.[47] The thylacine genome was reconstructed by using the genome editing method. The Tasmanian devil was used as a reference for the assembly of the full nuclear genome.[48] Andrew J. Pask from the University of Melbourne has stated that the next step toward de-extinction will be to create a functional genome, which will require extensive research and development, estimating that a full attempt to resurrect the species may be possible as early as 2027.[47]

In August 2022, the University of Melbourne and Colossal Biosciences announced a partnership to accelerate de-extinction of the thylacine via genetic modification of one of its closest living relatives, the fat-tailed dunnart.[49] In 2024, a 99.9% complete genome of the thylacine was created from a well-preserved skull that is estimated to be 110 years old.[50]

Passenger pigeon

[edit]

The passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) numbered in the billions before being wiped out due to unsustainable commercial hunting and habitat loss during the early 20th century. The non-profit Revive & Restore obtained DNA from the passenger pigeon from museum specimens and skins; however, this DNA is degraded because it is so old. For this reason, simple cloning would not be an effective way to perform de-extinction for this species because parts of the genome would be missing. Instead, Revive & Restore focuses on identifying mutations in the DNA that would cause a phenotypic difference between the extinct passenger pigeon and its closest living relative, the band-tailed pigeon. In doing this, they can determine how to modify the DNA of the band-tailed pigeon to change the traits to mimic the traits of the passenger pigeon. In this sense, the de-extinct passenger pigeon would not be genetically identical to the extinct passenger pigeon, but it would have the same traits. In 2015, the de-extinct passenger pigeon hybrid was forecast ready for captive breeding by 2025 and released into the wild by 2030.[51]

Bush moa

[edit]

The bush moa, also known as the little bush moa or lesser moa (Anomalopteryx didiformis) is a slender species of moa slightly larger than a turkey that went extinct abruptly, around 500–600 years ago following the arrival and proliferation of the Māori people in New Zealand, as well as the introduction of Polynesian dogs.[52] Scientists at Harvard University assembled the first nearly complete genome of the species from toe bones, thus bringing the species a step closer to de-extinction.[53] The New Zealand politician, Trevor Mallard has also previously suggested bringing back a medium-sized species of moa.[54] The proxy of the species will likely be the emu.[55]

Maclear's rat

[edit]

The Maclear's rat (Rattus macleari), also known as the Christmas Island rat, was a large rat endemic to Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean. It is believed Maclear's rat might have been responsible for keeping the population of Christmas Island red crab in check. It is thought that the accidental introduction of black rats by the Challenger expedition infected the Maclear's rats with a disease (possibly a trypanosome),[56] which resulted in the species' decline.[57] The last recorded sighting was in 1903.[58] In March 2022, researchers discovered the Maclear's rat shared about 95% of its genes with the living brown rat, thus sparking hopes in bringing the species back to life. Although scientists were mostly successful in using CRISPR technology to edit the DNA of the living species to match that of the extinct one, a few key genes were missing, which would mean resurrected rats would not be genetically pure replicas.[59]

Dodo

[edit]

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) was a flightless bird endemic to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Due to various factors such as the inability to feel fear caused by isolation from significant predators, predation from humans and introduced invasive species such as pigs, dogs, cats, rats, and crab-eating macaques, competition for food with invasive species, habitat loss, and the birds naturally slow reproduction, the species' numbers declined rapidly.[60] The last widely accepted recorded sighting was in 1662. Since then, the bird has become a symbol for extinction and is often cited as the primary example of man-made extinction.[61] In January 2023, Colossal Biosciences announced their project to revive the dodo alongside their previously announced projects for reviving the woolly mammoth and thylacine in hopes of restoring biodiversity to Mauritius and changing the dodo's status as a symbol of extinction to de-extinction.[62] [63]

Steller's sea cow

[edit]

The Steller's sea cow was a sirenian endemic to Bering Sea between Russia and the United States but had a much larger range during the Pleistocene. First described by Georg Wilhelm Steller in 1741. It was hunted to extinction 27 years later due to its buoyancy making it an easy target for humans hunting it for its meat and fur in addition to an already low population caused by climate change. In 2021, the nuclear genome of the species was sequenced.[64] In late 2022, a group of Russian scientists funded by Sergei Bachin began their project to revive and reintroduce the giant sirenian to its former range in the 18th century to restore its kelp forest ecosystem. Artic Sirenia plans to revive the species through genome editing of the dugong, but they need an artificial womb to conceive a live animal due to lack of an adequate surrogate species.[65] Ben Lamm of Colossal Biosciences has also expressed desire to revive the species once his company develops an artificial womb.[66]

Northern white rhinoceros

[edit]

The northern white rhinoceros or northern white rhino (Ceratotherium simum cottoni) is a subspecies of the of white rhinoceros endemic to East and Central Africa south of the Sahara. Due to widespread and uncontrollable poaching and civil warfare in their former range, the subspecies' numbers dropped quickly over the course of the late 1900s and early 2000s.[67][68] Unlike the majority of the potential candidates for de-extinction, the northern white rhinoceros is not extinct, but functionally extinct and is believed to be extinct in the wild with only two known female members left, Najin and Fatu who reside on the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya.[69] The BioRescue Team in collaboration with Colossal Biosciences plan to implement 30 northern white rhinoceros embryos made from egg cells collected from Najin and Fatu and preserved sperm from dead male individuals into female southern white rhinoceros by the end of 2024.[12][70]

Ivory-billed woodpecker

[edit]

The ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) is the largest woodpecker endemic to the United States with a subspecies in Cuba. The species numbers have declined since the late 1800s due to logging and hunting.[71] Similar to the northern white rhinoceros, the ivory-billed woodpecker is not completely extinct, but functionally extinct with occasional sightings that suggest that 50 or less individuals are left.[72] In October 2024, Colossal Biosciences announced their non-profit Colossal Foundation, a foundation dedicated to conservation of extant species with their first projects being the Sumatran rhinoceros, vaquita, red wolf, pink pigeon, northern quoll, and ivory-billed woodpecker. Colossal plans to revive or rediscover the species through genome editing of its closest living relatives and using drones and AI to identify any potential remaining individuals in the wild.[73][74]

Heath hen

[edit]

The heath hen (Tympanuchus cupido cupido) was a subspecies of greater prairie chicken endemic to the heathland barrens of coastal North America. It is even speculated that the pilgrims' first Thanksgiving featured this bird as the main course instead of wild turkey.[75] Due to overhunting caused by its perceived abundancy, the population became extinct in mainland North America by 1870, leaving a population of 300 individuals left on Martha's Vineyard. Despite conservation efforts, the subspecies became extinct in 1932 following the disappearance and presumed death of Booming Ben, the final known member of the subspecies. In the summer of 2014, non-profit organisation, Revive & Restore held a meeting with the community of Martha's Vineyard to announce their project to revive the heath hen in hopes of restoring and maintaining the sandplain grasslands.[76][77] On April 8th, 2020, germs cells were collected from greater prairie chicken eggs at Texas A&M.[78][79]

Yangtze giant softshell turtle

[edit]

The Yangtze giant softshell turtle (Rafetus swinhoei) is a softshell turtle endemic to China and Vietnam and is possibly the largest living freshwater turtle. Due to various factors such as habitat loss, wildlife trafficking, trophy hunting, and the Vietnam War, the species population has been reduced to only three male individuals, rendering it functionally extinct similar to the northern white rhinoceros and ivory-billed woodpecker.[80][81] There is one captive individual in Suzhou Zoo in China, and two wild individuals at Dong Mo Lake in Vietnam. Efforts to save the species from extinction through various means of assisted reproduction in captivity have been ongoing since 2009 by the Suzhou Zoo and Turtle Survival Alliance.

Despite efforts to breed the turtles naturally, the eggs laid by the final known female were all infertile and unviable. In May 2015, artificial insemination was performed for the first time in the species.[82] In July of the same year, the female laid 89 eggs, but like all previous natural attempts, they were all unviable.[83] In April 2019, the female individual at the zoo died after another failed artificial insemination attempt.[84] In 2020, a female was discovered in the wild, reigniting hope for the survival of the species.[85] However, this individual was found dead in early 2023.[86] Several searches across China and Vietnam are currently underway to locate female individuals to breed with the final known males, or to undergo artificial insemination.[87][88][89]

Future potential candidates for de-extinction

[edit]A "De-extinction Task Force" was established in April 2014 under the auspices of the Species Survival Commission (SSC) and charged with drafting a set of Guiding Principles on Creating Proxies of Extinct Species for Conservation Benefit to position the IUCN SSC on the rapidly emerging technological feasibility of creating a proxy of an extinct species.[90]

Birds

[edit]- Giant moa – The tallest birds to have ever lived, but not as heavy as the elephant bird. Both the northern and southern species became extinct by 1500 due to overhunting by the Polynesian settlers and Māori in New Zealand.[91]

- Elephant bird – The heaviest birds to have ever lived, the elephant birds were driven to extinction by the early colonization of Madagascar. Ancient DNA has been obtained from the eggshells but may be too degraded for use in de-extinction.[91][92]

- Carolina parakeet - One of the only indigenous parrots to North America, it was driven to extinction by destruction of its habitat, overhunting, competition from introduced honeybees, and persecution for crop damages. Hundreds of specimens with viable DNA still exist in museums around the world, making them a prime candidate for revival. In 2019, a full genome of the carolina parakeet was sequenced.[91][93][94]

- Great auk - A flightless bird native to the North Atlantic similar to the penguin. The great auk went extinct in the 1800s due to overhunting by humans for food. The last two known great auks lived on an island near Iceland and were clubbed to death by sailors. There have been no known sightings since.[95] The great auk has been identified as a good candidate for de-extinction by Revive and Restore, a non-profit organization. Because the great auk is extinct it cannot be cloned, but its DNA can be used to alter the genome of its closest relative, the razorbill, and breed the hybrids to create a species that will be very similar to the original great auks. The plan is to introduce them back into their original habitat, which they would then share with razorbills and puffins, who are also at risk for extinction. This would help restore the biodiversity and restore that part of the ecosystem.[96]

- Imperial woodpecker – A large possibly extinct woodpecker endemic to Mexico that has not been seen since 1956 due to habitat destruction and hunting. The Federal government of Mexico has considered the species extinct since 2001, 47 years after the last widely accepted sighting. However, they have conservation plans if the species is rediscovered or revived.[91][93][97]

- Cuban macaw – A colourful macaw that was native to Cuba and Isla de la Juventud. It became extinct in the late 19th century due to overhunting, pet trade, and habitat loss. [91][93]

- Labrador duck – A duck that was native to North America. it became extinct in the late 19th century due to colonisation in their former range combined with an already naturally low population. It is also the first known endemic North American bird species to become extinct following the Columbian Exchange.[98] [91][93]

- Huia – A species of Callaeidae that was native to New Zealand. It became extinct in 1907 due to overhunting from both the Māori and European settlers, habitat loss, and predation from introduced invasive species. In 1999, students of Hastings Boys' High School proposed the idea of de-extinction of the huia, the school's emblem through cloning.[99] The Ngāti Huia tribe approved of the idea and the de-extinction process would have been performed by the University of Otago with $100,000 funding from a Californian based internet startup.[100] However, due to the poor state of DNA in the specimens at Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, a complete huia genome could not be created, making this method of de-extinction improbable to succeed.[101] [91][93]

- Moho – An entire genus of Hawaiian birds that were native to various islands in Hawaii. The genus became extinct in 1987 following the extinction of its final living member, Kauaʻi ʻōʻō. The reasons for the genus' decline were overhunting for their plumage, habitat loss caused by both colonisation of Hawaii and natural disasters, mosquito-borne diseases, and predation from introduced invasive species. [91][93]

Mammals

[edit]- Caribbean monk seal – A species of monk seal that was native to the Caribbean. It became extinct in 1950 due to poaching and starvation caused by overfishing of its natural prey.[91][93]

- Irish elk – The largest deer to have ever lived, formerly inhabiting Eurasia from present day Ireland to present day Sibera during the Pleistocene. It became extinct 5-10 thousand years ago due to suspected overhunting. [91][93]

- Cave lion – A species of Panthera endemic to Eurasia and Northwest North America during the Pleistocene. It is estimated that the species died out 14-15 thousand years ago due to climate change and low genetic diversity. The discovery of preserved cubs in the Sakha Republic ignited a project to clone the animal.[102][103]

- Steppe bison – The ancestor of all modern bison in North America, formerly endemic to Western Europe to eastern Beringia in North America during the Late Pleistocene. The discovery of the mummified steppe bison of 9,000 years ago could help people clone the ancient bison species back, even though the steppe bison would not be the first to be "resurrected".[104] Russian and South Korean scientists are collaborating to clone steppe bison in the future, using DNA preserved from an 8,000-year-old tail,[105][106] in wood bison, which themselves have been introduced to Yakutia to fulfill a similar niche.

- Tarpan – A population of free-ranging horses in Europe that went extinct in 1909. Much like the aurochs, there have been many attempts to breed tarpan-like horses from domestic horses, the first being by the Heck brothers, creating the Heck horse as a result. Though it is not a genetic copy, it is claimed to bear many similarities to the tarpan.[107] Other attempts were made to create tarpan-like horses. A breeder named Harry Hegardt was able to breed a line of horses from American Mustangs.[108] Other breeds of supposedly tarpan-like horse include the Konik and Strobel's horse.[citation needed]

- Baiji – A freshwater dolphin native to the Yangtze River in China. Unlike most potential candidates for de-extinction, the baiji is not completely extinct, but instead functionally extinct with a low population in the wild due to entanglement in nets, collision with boats, and pollution of the Yangtze River with occasional sightings, with the most recent in 2024.[109] There are plans to help save the species if a living specimen is found.[93]

- Vaquita – The smallest cetacean to have ever lived that is endemic to the upper Gulf of California in Mexico. Similar to the baiji, the vaquita is not completely extinct, but functionally extinct with an estimate of 8 or less members left due to entanglement in gillnets meant to poach totoabas, a fish with a highly valued swim bladder on black markets due to its perceived medicinal values.[110][111] In October 2024, Colossal Biosciences launched their Colossal Foundation, a non-profit foundation dedicated to conservation of extant species with one of their first projects being the vaquita. In addition to using technology to monitor the final remaining individuals, they aim to collect tissue samples from vaquitas in order to revive it if it does become extinct in the near future.[112]

- Woolly rhinoceros – A species of rhinoceros that was endemic to Northern Eurasia during the Pleistocene. It is believed to have become extinct as a result of both climate change and overhunting by early humans. In November 2023, scientists managed to create a woolly rhinoceros genome from faeces of cave hyenas in addition to the existence of frozen specimens.[113][114] However, the woolly rhinoceros' closest living relative is the critically endangered Sumatran rhinoceros with an estimate of only 80 individuals left in the wild, which presents ethical dilemmas similar to the woolly mammoth.[91][93]

- Cave bear – A species of bear that was endemic to Eurasia during the Pleistocene. It is estimated to have become extinct 24 thousand years ago due to climate change and suspected competition with early humans.[91][93]

- Castoroides – An entire genus of giant beavers endemic to North America during the Pleistocene. It is estimated that the species died out due to overhunting by early humans. Beth Shapiro of Colossal Biosciences has expressed interest in reviving a species from this genus.[115]

- Arctodus – An entire genus of short-faced bears endemic to North America during the Pleistocene. It is estimated that they became extinct 12 thousand years ago following the death of its final member, Arctodus simus due to climate change and low genetic diversity. Beth Shapiro of Colossal Biosciences has expressed interest in reviving one of the two species from the genus.[115]

Reptiles

[edit]- Floreana giant tortoise – A subspecies of the Galápagos tortoise that became extinct in 1950. In 2008, mitochondrial DNA from the Floreana tortoise species was found in museum specimens. In theory, a breeding program could be established to "resurrect" a pure Floreana species from living hybrids.[116][117]

Amphibians

[edit]- Gastric-brooding frog – An entire genus of ground frogs that were native to Queensland, Australia. They became extinct in the mid-1980s primarily due to Chytridiomycosis. In 2013, scientists in Australia successfully created a living embryo from non-living preserved genetic material, and hope that by using somatic-cell nuclear transfer methods, they can produce an embryo that can survive to the tadpole stage.[91][118]

Insects

[edit]

- Xerces blue – A species of butterfly that was native to the Sunset District of San Francisco in the American state of California. It is estimated that the species became extinct in the early 1940s due to urbanization of their former habitat. Similar species to the Xerces blue, such as Glaucopsyche lygdamus and the Palos Verdes blue, have been released into the Xerces blue's former range to substitute its role. On April 15, 2024, non-profit organisation Revive & Restore announced the early stages of their plans to potentially revive the species.[91][119]

Plants

[edit]- Paschalococos – A genus of coccoid palm trees that were native to Easter Island, Chile. It is believed to have become extinct around 1650 due to its disappearance from the pollen records.[91]

- Hyophorbe amaricaulis – A species of palm tree from the Arecales family that is native to the island of Mauritius. Unlike the majority of potential candidates, this palm is not completely extinct, but functionally extinct and is believed to be extinct in the wild with only one known specimen left in the Curepipe Botanic Gardens. In 2010, there was an attempt to revive the species through germination in vitro in which Isolated and growing embryos were extracted from seeds in tissue culture, but these seedlings only lived for three months.[11]

Successful de-extinctions

[edit]

Judean date palm

[edit]The Judean date palm is a species of date palm native to Judea that is estimated to have originally become extinct around the 15th century due to climate change and human activity in the region.[120] In 2005, preserved seeds found in the 1960s excavations of Herod the Great's palace were given to Sarah Sallon by Bar-Ilan University after she came up with the initiative to germinate some ancient seeds.[121] Sallon later challenged her friend, Elaine Solowey of the Center for Sustainable Agriculture at the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies with the task of germinating the seeds. Solowey managed to revive several of the provided seeds after hydrating them with a common household baby bottle warmer along with average fertiliser and growth hormones.[122] The first plant grown was named after Lamech's father, Methuselah, the oldest living man in the Bible. In 2012, there were plans to crossbreed the male palm with what was considered its closest living relative, the Hayani date of Egypt to generate fruit by 2022. However, two female Judean date palms have been sprouted since then.[123] By 2015 Methuselah had produced pollen that has been used successfully to pollinate female date palms. In June 2021, one of the female plants, Hannah, produced dates. The harvested fruits are currently being studied to determine their properties and nutritional values.[124] The de-extinct Judean date palms are currently at a Kibbutz located in Ketura, Israel.[125]

Rastreador Brasilerio

[edit]

The Rastreador Brasilerio (Brazilian Tracker) is a large scent hound from Brazil that was bred in the 1950s to hunt jaguars and wild pigs. It was originally declared extinct and delisted by the Fédération Cynologique Internationale and Confederação Brasileira de Cinofilia in 1973 due to tick-borne diseases and subsequent poisoning from insecticides in attempt to get rid of the ectoparasites.[126] In the early 2000s, a group named Grupo de Apoio ao Resgate do Rastreador Brasileiro (Brazilian Tracker Rescue Support Group) dedicated to reviving the breed and having it relisted by Confederação Brasileira de Cinofilia began work to locate dogs in Brazil that had genetics of the extinct breed to breed a purebred Rastreador Brasilerio.[127] In 2013, the breed was de-extinct through preservation breeding from descendants of the final original members and was relisted by the FCI.[128][129]

Unknown Commiphora

[edit]

In 2010, Sarah Sallon of Arava Institute for Environmental Studies grew a seed found in excavations of a cave in the northern Judean desert in 1986. The specimen, Sheba reached maturity in 2024 and is believed to be an entirely new species of Commiphora with many believing that she may be the tsori or Judean balsam, plants that are said to have healing properties in the Bible.[130][131]

Montreal melon

[edit]

The Montreal melon, also known as the Montral market muskmelon, Montreal nutmeg melon, and in French as melon de Montréal (Melon of/from Montreal) is a cultivar of melon native to Canada and traditionally grown around the Montreal area. Despite its status as a delicacy on the east coast of North America, the Montreal melon disappeared from farms and was presumed extinct by the 1920s due to urbanisation in the region and being ill-suited for agribusiness. In 1996, seeds of the lost melon were discovered in a seed bank in the American state of Iowa. Since then, the plant has been reintroduced to its former range by local gardeners.[132][133]

See also

[edit]- Breeding back

- Preservation breeding

- Cryoconservation of animal genetic resources

- Endangered species

- Functional extinction

- Endling

- Holocene extinction

- List of introduced species

- Pleistocene Park

- Pleistocene rewilding

- Colossal Biosciences

- Arava Institute for Environmental Studies

- List of resurrected species

References

[edit]- ^ Yin, Steph (20 March 2017). "We Might Soon Resurrect Extinct Species. Is It Worth the Cost?". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ^ Sherkow, Jacob S.; Greely, Henry T. (2013-05-05). "What If Extinction Is Not Forever?". Science. 340 (6128): 32–33. Bibcode:2013Sci...340...32S. doi:10.1126/science.1236965. hdl:2142/111005. PMID 23559235.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Beth (2016-08-09). "Pathways to de-extinction: How close can we get to resurrection of an extinct species?". Functional Ecology. 31 (5): 996–1002. Bibcode:2017FuEco..31..996S. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12705. ISSN 0269-8463. S2CID 15257110.

- ^ a b Shultz, David (2016-09-23). "Should we bring extinct species back from the dead?". Science. AAAS. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- ^ a b c Wadman, Meredith (2007). "Dolly: A decade on". Nature. 445 (7130): 800–801. doi:10.1038/445800a. PMID 17314939. S2CID 6042005.

- ^ a b Palermo, Giulia; Ricci, Clarisse G.; McCammon, J. Andrew (April 2019). "The invisible dance of CRISPR-Cas9. Simulations unveil the molecular side of the gene-editing revolution". Physics Today. 72 (4): 30–36. doi:10.1063/PT.3.4182. ISSN 0031-9228. PMC 6738945. PMID 31511751.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Beth (2017). "Pathways to de-extinction: how close can we get to resurrection of an extinct species?". Functional Ecology. 31 (5): 996–1002. Bibcode:2017FuEco..31..996S. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12705. S2CID 15257110.

- ^ Hume, Julian P.; Martill, David (2019-05-08). "Repeated evolution of flightlessness in Dryolimnas rails (Aves: Rallidae) after extinction and recolonization on Aldabra". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 186 (3): 666–672. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz018.

- ^ Harris, Glenn (2019-05-09). "The bird that came back from the dead". EurekAlert!.

- ^ Marinelli, Janet (12 July 2023). "Back from the Dead: New Hope for Resurrecting Extinct Plants". Yale Environment 360. Yale School of the Environment.

- ^ a b Sarasan, Viswambharan (2010-12-01). "Importance of in vitro technology to future conservation programmes worldwide". Kew Bulletin. 65 (4): 549–554. Bibcode:2010KewBu..65..549S. doi:10.1007/s12225-011-9250-7. ISSN 1874-933X.

- ^ a b Kluger, Jeffrey; Vitale, Photos by Ami (2024-01-25). "An Inside Look at the Embryo Transplant That May Help Save the Northern White Rhino". TIME. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

- ^ a b Brand, Stewart (2014-01-13). "De-Extinction Debate: Should We Bring Back the Woolly Mammoth?". Yale Environment 360. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

- ^ Bennett, Joseph (25 March 2015). "Biodiversity gains from efficient use of private sponsorship for flagship species conservation". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 282 (1805): 20142693. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2693. PMC 4389608. PMID 25808885.

- ^ Whittle, Patrick; et al. (12 Dec 2014). "Re-creation tourism: de-extinction and its implications for nature-based recreation". Current Issues in Tourism. 18 (10): 908–912. doi:10.1080/13683500.2015.1031727. S2CID 154878733.

- ^ Bouchard, Anthony (2017-03-20). "The Pros and Cons of Reviving Extinct Animal Species | Plants And Animals". LabRoots. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

- ^ a b Kasperbauer, T. J. (2017-01-02). "Should We Bring Back the Passenger Pigeon? The Ethics of De-Extinction". Ethics, Policy & Environment. 20 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/21550085.2017.1291831. ISSN 2155-0085. S2CID 90369318.

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul; Ehrlich, Anne H. (2014-01-13). "The Case Against De-Extinction: It's a Fascinating but Dumb Idea". Yale Environment 360. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

- ^ Richmond, Douglas J.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (2016). "The potential and pitfalls of de-extinction". Zoologica Scripta. 45 (S1): 22–36. doi:10.1111/zsc.12212. ISSN 1463-6409.

- ^ Charles Q. Choi (December 8, 2011). "Woolly Mammoths Could Be Cloned Someday, Scientist Says". Live Science.

- ^ Worrall, Simon (2017-07-09). "We Could Resurrect the Woolly Mammoth. Here's How". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on September 11, 2019. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- ^ a b Treu, Zachary (2014-03-14). "Welcome to Pleistocene Park: Russian scientists say they have a 'high chance' of cloning a woolly mammoth". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Stone, R. (1999). "Cloning the Woolly Mammoth". Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Mammoth Genome Project". Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Lendon, B. (17 January 2011). "Scientists trying to clone, resurrect extinct mammoth". CNN. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ Michael Greshko (September 13, 2021). "Mammoth-elephant hybrids could be created within the decade. Should they be?". National Geographic.

- ^ a b Koebler, Jason (2014-05-21). "The Plan to Turn Elephants Into Woolly Mammoths Is Already Underway". Motherboard. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Hendrik Poinar (30 May 2013). "Hendrik Poinar: Bring back the woolly mammoth! - Talk Video - TED.com". Ted.com. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ a b Church, George. "George Church: De-Extinction Is a Good Idea." Scientific American, 1 Sept. 2013. Web. 13 Oct. 2016.

- ^ "Why Efforts to Bring Extinct Species Back from the Dead Miss the Point". Scientific American. June 2013. Retrieved 2021-03-11.

- ^ "First extinct-animal clone created". National Geographic (nationalgeographic.com). 2009-02-10. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ a b Rincon, Paul (2013-11-22). "Fresh effort to clone extinct animal". BBC News. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Elcacho, Joaquim (2013-11-26). "¿Es posible clonar el bucardo, la cabra extinguida del Pirineo?". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-04-11.

- ^ Tikhonov, A. (2008). "Bos primigenius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T136721A4332142. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T136721A4332142.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "BBC Nature – Cattle and aurochs videos, news and facts". bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2014-04-11. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Rokosz, Mieczyslaw (1995). "History of the aurochs (Bos taurus primigenius) in Poland". Animal Genetic Resources Information. 16: 5–12. doi:10.1017/S1014233900004582.

- ^ Lawson, Kristan (2014-09-10). "'Jurassic farm' can bring prehistoric barnyard animals back from extinction". Modern Farmer. Archived from the original on 2015-03-08. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Pais, Bárbara. "TaurOs Programme". Atnatureza.org. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 23 November 2014. "TaurOs Programme fact sheet" (PDF). Rewilding Europe (Press release). 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2023-03-24.

- ^ "Tauros Programme". Rewilding Europe (Rewildingeurope.com). Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ "Aurochs". True Nature Foundation (truenaturefoundation.org). Archived from the original on 2015-01-16. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ^ "The Aurochs: Born to be wild". Rewilding Europe (Rewildingeurope.com). Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Rodriguez, Debra L. (1999). "Equus quagga". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ "OBJECTIVES :: The Quagga Project :: South Africa". Quaggaproject.org. Archived from the original on 1 December 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Harley, Eric H.; Knight, Michael H.; Lardner, Craig; Wooding, Bernard; Gregor, Michael (2009). "The Quagga Project: Progress over 20 Years of Selective Breeding". South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 39 (2): 155–163. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.653.4113. doi:10.3957/056.039.0206. S2CID 31506168.

- ^ Paddle (2000)[broken anchor], p. 195.

- ^ "National Threatened Species Day". Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government. 2006. Archived from the original on July 9, 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- ^ a b "Tasmanian Tiger Genome May Be First Step Toward De-Extinction". 2017-12-11. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved 2018-08-25.

- ^ Feigin, Charles Y.; Newton, Axel H.; Doronina, Liliya; Schmitz, Jürgen; Hipsley, Christy A.; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Gower, Graham; Llamas, Bastien; Soubrier, Julien (2018). "Genome of the Tasmanian tiger provides insights into the evolution and demography of an extinct marsupial carnivore". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (1): 182–192. Bibcode:2017NatEE...2..182F. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0417-y. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 29230027.

- ^ "Lab takes 'giant leap' toward thylacine de-extinction with Colossal genetic engineering technology partnership" (Press release). The University of Melbourne. 2022-08-16. Archived from the original on 2022-08-16. Retrieved 2022-08-16.

- ^ "MSN". www.msn.com. Retrieved 2024-10-20.

- ^ Journal, Amy Dockser Marcus Wall Street. "Passenger Pigeon Project Update". Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ "Little bush moa | New Zealand Birds Online". nzbirdsonline.org.nz. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ "Scientists reconstruct the genome of a moa, a bird extinct for 700 years". STAT. 2018-02-27. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ "Time to bring back... the moa". Stuff. 10 July 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Begley, Sharon (2018-02-27). "With DNA from a museum specimen, scientists reconstruct the genome of a bird extinct for 700 years". STAT. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ Pickering J. & Norris C.A. (1996). "New evidence concerning the extinction of the endemic murid Rattus macleari from Christmas Island, Indian Ocean". Australian Mammalogy. 19: 19–25.

- ^ Wyatt KB, Campos PF, Gilbert MT, Kolokotronis SO, Hynes WH, et al. (2008). "Historical mammal extinction on Christmas Island (Indian Ocean) correlates with introduced infectious disease"

- ^ Flannery, Tim & Schouten, Peter (2001). A Gap in Nature: Discovering the World's Extinct Animals. Atlantic Monthly Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-87113-797-5.

- ^ Lin J, Duchêne D, Carøe C, Smith O, Ciucani MM, Niemann J, Richmond D, Greenwood AD, MacPhee R, Zhang G, Gopalakrishnan S, Gilbert MTP (11 April 2022). "Probing the genomic limits of de-extinction in the Christmas Island rat". Current Biology. 32 (7): 1650–1656.e3. Bibcode:2022CBio...32E1650L. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.02.027. hdl:11250/3052724. PMC 9044923. PMID 35271794.

- ^ Hume, Julian P. (2017). Extinct birds (Second ed.). London New York: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-1-4729-3744-5.

- ^ Turvey, Samuel T.; Cheke, Anthony S. (June 2008). "Dead as a dodo: the fortuitous rise to fame of an extinction icon". Historical Biology. 20 (2): 149–163. Bibcode:2008HBio...20..149T. doi:10.1080/08912960802376199. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ Snider, Mike. "Scientists are trying to resurrect the dodo – centuries after the bird famously went extinct". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

- ^ "Dodo | Reviving the Dodo". Colossal. 2023-01-31. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

- ^ Sharko, Fedor S.; Boulygina, Eugenia S.; Tsygankova, Svetlana V.; Slobodova, Natalia V.; Alekseev, Dmitry A.; Krasivskaya, Anna A.; Rastorguev, Sergey M.; Tikhonov, Alexei N.; Nedoluzhko, Artem V. (2021-04-13). "Steller's sea cow genome suggests this species began going extinct before the arrival of Paleolithic humans". Nature Communications. 12 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22567-5. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8044168.

- ^ "Arctic Sirenia". www.arcticsirenia.com. Retrieved 2024-11-18.

- ^ Writer, Anna Skinner Senior; Assignment, General (2023-12-01). "Extinct animals could suddenly be brought back to life". Newsweek. Retrieved 2024-11-18.

- ^ "Northern White Rhino". 2007-10-23. Archived from the original on 2007-10-23. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

- ^ Smith, Kes Hillman (July–December 2001). "Status of northern white rhinos and elephants in Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo, during the wars" (PDF). Pachyderm Journal.

- ^ "Just two northern white rhinos are left on Earth. A new breakthrough offers hope". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

- ^ "Colossal Biosciences Joins BioRescue in Its Mission to Save the Northern White Rhino From Extinction | BioSpace". 2024-02-07. Archived from the original on 2024-02-07. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

- ^ Recovery Plan for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus Principalis) (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Southeast Region. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-08.

- ^ "Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) - BirdLife species factsheet". datazone.birdlife.org. Retrieved 2024-08-26.

- ^ Jacobo, Julia (2024-10-01). "How the process of de-extinction will be used to restore this fabled species". ABC News. Retrieved 2024-10-02.

- ^ "The Colossal Foundation Aims to Save Threatened Species with De-Extinction Science". Yahoo Entertainment. 2024-10-01. Retrieved 2024-10-02.

- ^ "The Original "Thanksgiving Turkey" is Now Extinct". IDA USA. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ "The Heath Hen Could Come Back". Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ "Heath Hen Debate Contains Vineyard DNA". The Vineyard Gazette - Martha's Vineyard News. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ "Heath Hen Project: Progress to Date". Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ Revive & Restore (2020-04-08). Greater Prairie Chicken In Mating Call and Stamping. Retrieved 2024-09-01 – via YouTube.

- ^ Department of Animal Science and Fishery, Faculty of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Bintulu Sarawak Campus, 97008 Bintulu, Sarawak, Malaysia; Al-Asif, Abdulla (2022). "A ray of hope in the darkness: What we have learned from Yangtze giant soft-shell turtle Rafetus swinhoei (Gray, 1873) conservation?" (PDF). Asian Journal of Conservation Biology. 11 (2): 167–168. doi:10.53562/ajcb.EN00022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Rafetus swinhoei field guide - Asian Turtle Conservation Network". web.archive.org. 2006-12-14. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ "Scientists Make Novel Attempt to Save Giant Turtle Species - NYTimes.com". web.archive.org. 2015-05-26. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ "First Artificial Breeding Attempt for World's Rarest Turtle Unsuccessful | Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA)". web.archive.org. 2015-09-10. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ "1 of world's 4 remaining giant softshell turtles dies – DW – 04/14/2019". dw.com. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ "World's Most Endangered Turtle Gets Some Good News In 2020". newsroom.wcs.org. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ Hanoi, Chris Humphrey / (2023-04-28). "Rare, Revered Reptile on Brink of Extinction After Last Female Dies". TIME. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ "Interview surveys in northern Vietnam look for remaining Swinhoe's softshell turtles in the wild". web.archive.org. 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ "The Yangtze Softshell Turtle – TURTLE ISLAND". web.archive.org. 2019-04-18. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ Price, Katie (2024-11-13). "There are Only 2 of These Turtles Left in the Wild". A-Z Animals. Retrieved 2024-12-06.

- ^ IUCN SSC (2016). IUCN SSC Guiding principles on Creating Proxies of Extinct Species for Conservation Benefit. Version 1.0. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN Species Survival Commission

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Candidate species | Revive & Restore". 2017-02-08. Archived from the original on 2017-02-08. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- ^ Alleyne, Richard (10 March 2010). "Extinct elephant bird of Madagascar could live again". Telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dodgson, Lindsay. "25 animals that scientists want to bring back from extinction". Business Insider. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ Smith, Kiona N. "Scientists Sequenced The Genome Of The Carolina Parakeet, America's Extinct Native Parrot". Forbes. Retrieved 2024-09-19.

- ^ "Bringing Them Back to Life". Magazine. 2013-04-01. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ "Can the great auk return from extinction? | Conservation | Earth Touch News". Earth Touch News Network. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/cop/16/prop/E-CoP16-Prop-21.pdf

- ^ Renko, Amanda. "EXTINCT: Seeking a bird last seen in 1878". Star-Gazette. Retrieved 2024-08-27.

- ^ "NZSM OnLine -- Ten years of New Zealand Science Monthly magazine". 2008-06-12. Archived from the original on 2008-06-12. Retrieved 2024-08-27.

- ^ Dorey, Emma (1999-08-01). "Huia cloned back to life?". Nature Biotechnology. 17 (8): 736. doi:10.1038/11628. ISSN 1546-1696. PMID 10429272.

- ^ "The last huia - Health - Science - The Listener". 2014-08-26. Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2024-08-27.

- ^ "South Koreans kick off efforts to clone extinct Siberian cave lions". siberiantimes.com. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ "Scientists to clone Ice Age cave lion". NewsComAu. 5 March 2016.

- ^ "9,000-year-old bison found mummified in Siberia". techtimes.com. 6 November 2014.

- ^ Surugue, Léa (2016-12-02). "Cloning ancient extinct bison sounds like sci-fi, but scientists hope to succeed within years". International Business Times UK. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "The remains of an 8,000 year old lunch: an extinct steppe bison's tail". siberiantimes.com. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "Breeds of Livestock - Tarpan Horse — Breeds of Livestock, Department of Animal Science". Breeds of Livestock. 28 June 2021.

- ^ Flaccus, Gillian (2002-07-15). "Couple revives prehistoric Tarpan horses from genes in mustangs". The Daily Courier.

- ^ "中华白鱀豚功能性灭绝十年后疑似重现长江,科考队称拍到两头_绿政公署_澎湃新闻-The Paper". m.thepaper.cn. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ Stickney • •, R. (2013-04-24). "Multi-Million Dollar Fish Bladder Factory Uncovered in Calexico". NBC 7 San Diego. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

- ^ devon11 (2024-06-11). "Vaquita Survey 2024 - Executive Summary". Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Innovates, Dallas; Murray, Lance (2024-10-01). "Colossal Launches The Colossal Foundation with $50M for 'BioVault' Biobanking, Genetic Rescues, and More". Dallas Innovates. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

- ^ Starr, Michelle (2023-11-02). "Europe's Wooly Rhino Genes Reconstructed From DNA in Predator Poop". ScienceAlert. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ Cassella, Carly (2021-01-02). "A Freakishly Well-Preserved Woolly Rhino Was Plucked From Siberia's Melting Tundra". ScienceAlert. Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ a b "First it was the dodo – now scientists want to resurrect the giant bear and jumbo beaver". The Telegraph. 2024-10-05. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ Poulakakis, N.; Glaberman, S.; Russello, M.; Beheregaray, L. B.; Ciofi, C.; Powell, J. R.; Caccone, A. (2008-10-07). "Historical DNA analysis reveals living descendants of an extinct species of Galápagos tortoise". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (40): 15464–15469. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10515464P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805340105. PMC 2563078. PMID 18809928.

- ^ Ludden, Maizy (2017-11-12). "Extinct tortoise species may return to the Galápagos thanks to SUNY-ESF professor - The Daily Orange - The Independent Student Newspaper of Syracuse, New York". The Daily Orange. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- ^ "Scientists successfully create living embryo of an extinct species". Archived from the original on 2017-11-16. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

- ^ Tuff, Kika. "Relative of extinct butterfly helps fill ecological void". Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ^ Issar, Arie S. (2004-08-05). Climate Changes during the Holocene and their Impact on Hydrological Systems. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-43640-3.

- ^ Zhang, Sarah (2020-02-05). "After 2,000 Years, These Seeds Have Finally Sprouted". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2024-08-18.

- ^ Sallon, Sarah; Cherif, Emira; Chabrillange, Nathalie; Solowey, Elaine; Gros-Balthazard, Muriel; Ivorra, Sarah; Terral, Jean-Frédéric; Egli, Markus; Aberlenc, Frédérique (2020-02-05). "Origins and insights into the historic Judean date palm based on genetic analysis of germinated ancient seeds and morphometric studies". Science Advances. 6 (6): eaax0384. Bibcode:2020SciA....6..384S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax0384. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7002127. PMID 32076636.

- ^ Kresh, Miriam (2012-03-25). "Ancient 2000-year old date pit sprouts - Green Prophet". Retrieved 2024-08-18.

- ^ "Extinct tree from the time of Jesus rises from the dead - BBC Reel". 2021-06-23. Archived from the original on 2021-06-23. Retrieved 2024-08-18.

- ^ "Dr. Elaine Solowey". Arava Institute for Environmental Studies. Retrieved 2024-08-18.

- ^ "DESENVOLVIMENTO E RECONHECIMENTO" (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2011-07-06. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

- ^ "Materia Revista Mania de Bicho" (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2011-07-06. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

- ^ "The Brazilian Tracker". The Academic Hound. 2023-08-15. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

- ^ "RASTREADOR BRASILEIRO". www.fci.be. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

- ^ Sallon, Sarah; Solowey, Elaine; Gostel, Morgan R.; Egli, Markus; Flematti, Gavin R.; Bohman, Björn; Schaeffer, Philippe; Adam, Pierre; Weeks, Andrea (2024-09-10). "Characterization and analysis of a Commiphora species germinated from an ancient seed suggests a possible connection to a species mentioned in the Bible". Communications Biology. 7 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1038/s42003-024-06721-5. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 11387840.

- ^ "MSN". www.msn.com. Retrieved 2024-10-11.

- ^ "Missing melon: Abstract- Canadian Geographic Magazine". 2011-10-11. Archived from the original on 2011-10-11. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ "Montreal melon, once thought to be all but gone, makes long-awaited comeback | Globalnews.ca". Global News. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

Further reading

[edit]- O'Connor, M.R. (2015). Resurrection Science: Conservation, De-Extinction and the Precarious Future of Wild Things. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9781137279293. Archived from the original on 2016-07-04.

- Shapiro, Beth (2015). How to Clone a Mammoth: The Science of De-Extinction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691157054.

- Pilcher, Helen (2016). Bring Back the King: The New Science of De-extinction Archived 2021-05-07 at the Wayback Machine. Bloomsbury Press ISBN 9781472912251

External links

[edit]- TEDx DeExtinction March 15, 2013 conference sponsored by Revive and Restore project of the Long Now Foundation, supported by TEDx and hosted by the National Geographic Society, that helped popularize the public understanding of the science of de-extinction. Video proceedings, meeting report, and links to press coverage freely available.

- De-Extinction: Bringing Extinct Species Back to Life April 2013 article by Carl Zimmer for National Geographic magazine reporting on 2013 conference.