Republic of Letters

The Republic of Letters (Res Publica Litterarum or Res Publica Literaria) was the long-distance intellectual community in the late 17th and 18th centuries in Europe and the Americas.[clarification needed] It fostered communication among the intellectuals of the Age of Enlightenment, or philosophes as they were called in France. These communities that transcended national boundaries formed the basis of a metaphysical Republic. Because of societal constraints on women, the Republic of Letters consisted mostly of men.

The Republic of Letters relied heavily on handwritten letters for correspondence.[1][clarification needed]

The first known occurrence of the term in its Latin form (Respublica literaria) is in a letter by Francesco Barbaro to Poggio Bracciolini dated July 6, 1417.[2] Currently, the consensus is that Pierre Bayle first translated the term in his journal Nouvelles de la République des Lettres in 1684. But there are some historians who disagree and some have gone so far as to say that its origin dates back to Plato's Republic.[3]

Historians are presently debating the importance of the Republic of Letters in influencing the Enlightenment.[4][page needed]

Academies

[edit]

The Royal Society primarily promoted science, which was undertaken by gentlemen of means acting independently. The Royal Society created its charters and established a system of governance. Its most famous leader was Isaac Newton, president from 1703 until his death in 1727. Other notable members include diarist John Evelyn, writer Thomas Sprat, and scientist Robert Hooke, the Society's first curator of experiments. It played an international role to adjudicate scientific findings, and published the journal "Philosophical Transactions" edited by Henry Oldenburg.[5]

The seventeenth century saw new academies open in France,[6] Germany,[7] and elsewhere. By 1700 they were found in most major cultural centers.[8][page needed]

Salons

[edit]

The salons were literary institutions that relied on a new ethic of polite sociability based on hospitality, distinction, and the entertainment of the elite. The salons were open to intellectuals, who used them to find protectors and sponsors and to fashion themselves as 'hommes du monde.' In the salons after 1770 there emerged a radical critique of worldliness, inspired by Rousseau. These radicals denounced the mechanisms of polite sociability and called for a new model of the independent writer, who would address the public and the nation.[9]

American salons

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2024) |

Printing press

[edit]The printing press also played a prominent role in the establishment of a community of scientists who could easily communicate their discoveries through the establishment of widely disseminated journals. Because of the printing press, authorship became more meaningful and profitable. The main reason was that it provided correspondence between the author and the person who owned the printing presses – the publisher. This correspondence allowed the author to have a greater control of its production and distribution.

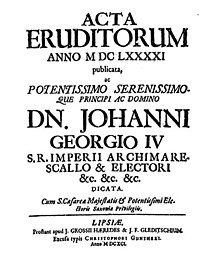

Journals

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2024) |

Transatlantic Republic of Letters

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2024) |

Historiographical debates

[edit]Anglo-American historians have turned their attention to the Enlightenment's dissemination and promotion, inquiring into the mechanisms by which it played a role in the collapse of the Ancien Régime.[10] This attention to the mechanisms of dissemination and promotion has led historians to debate the importance of the Republic of Letters during the Enlightenment.

Enlightenment as a rhetoric

[edit]In 1994, Dena Goodman published The Republic of Letters: A Cultural History of the French Enlightenment.

Engendering the Republic of Letters

[edit]In 2003, Susan Dalton published Engendering the Republic of Letters: Reconnecting Public and Private Spheres. Dalton supports Dena Goodman's view that women played a role in the Enlightenment.[11]

Conduct and community

[edit]In 1995, Anne Goldgar published Impolite Learning: Conduct and Community in the Republic of Letters, 1680–1750. Goldgar argues that, in the transitional period between the 17th century and the Enlightenment, the most important common concern by members of the Republic was their own conduct. In the conception of its own members, ideology, religion, political philosophy, scientific strategy, or any other intellectual or philosophical framework were not as important as their own identity as a community.[12]

Intellectual transparency and laicizations

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2024) |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Goodman 1994, p. 17.

- ^ Bots & Waquet 1997, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Lambe 1988, p. 273.

- ^ Mokyr 2017.

- ^ Hunter 2010, pp. 34–40.

- ^ Stroup 1990.

- ^ Evans 1977.

- ^ Jacob 2006.

- ^ Lilti 2005a, pp. 415–45.

- ^ Brockliss 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Dalton 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Brockliss 2002, p. 7.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bots, Hans; Waquet, Françoise (1997), La République des lettres (in French), Paris, France & Brussels, Belgium: Belin & De Boeck, ISBN 9782701121116

- Brockliss, L. W. B. (2002), Calvet's Web: Enlightenment and the Republic of Letters in Eighteenth-Century France, Oxford, England & New York, NY: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199247486

- Casanova, Pascale (2004) [1999], The World Republic of Letters, translated by DeBevoise, M. B., Cambridge, MA & London, England: Harvard University Press, ISBN 9780674013452

- Dalton, Susan (2003), Engendering the Republic of Letters: Reconnecting Public and Private Spheres, Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press, ISBN 9780773526181

- Daston, Lorraine (1991), "The Ideal and Reality of the Republic of Letters in the Enlightenment", Science in Context, 4 (2): 367–386, doi:10.1017/s0269889700001010

- Dibon, Paul (1978), "Communication in the Respublica Literaria of the 17th Century", Res Publica Litterarum, 1: 43–55, ISSN 0275-4304

- Evans, R. J. W. (1977), "Learned Societies in Germany in the Seventeenth Century", European History Quarterly, 7 (2): 129–151, doi:10.1177/026569147700700201, S2CID 143795722

- Feingold, Mordechai, ed. (2003), Jesuit Science and the Republic of Letters, Cambridge, MA & London, England: MIT Press, ISBN 9780262062343

- Fiering, Norman (1976), "The Transatlantic Republic of Letters: A Note on the Circulation of Learned Periodicals to Early Eighteenth-Century America", William and Mary Quarterly, 33 (4): 642–660, doi:10.2307/1921719, JSTOR 1921719.

- Furey, Constance M. (2006), Erasmus, Contarini, and the Religious Republic of Letters, Cambridge, England & New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521849876

- Füssel, Marian (2006), "'The Charlatanry of the Learned': On the Moral Economy of the Republic of Letters in Eighteenth-Century Germany", Cultural and Social History, 3 (3): 287–300, doi:10.1191/1478003806cs062oa, S2CID 145805291

- Goldgar, Anne (1995), Impolite Learning: Conduct and Community in the Republic of Letters, 1680–1750, New Haven, CT & London, England: Yale University Press, ISBN 9780300053593

- Goodman, Dena (1991), "Governing the Republic of Letters: The Politics of Culture in the French Enlightenment", History of European Ideas, 13 (3): 183–199, doi:10.1016/0191-6599(91)90180-7

- Goodman, Dena (1994), The Republic of Letters: A Cultural History of the French Enlightenment, Ithaca, NY & London, England: Cornell University Press, ISBN 9780801429682

- Hunter, Michael (November 2010), "The Great Experiment: The Royal Society", History Today, vol. 60, no. 11, pp. 34–40, retrieved 2023-06-21

- Israel, Jonathan (2001), Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity, 1650–1750, Oxford, England & New York, NY: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780198206088

- Jacob, Margaret C. (2006), Strangers Nowhere in the World: The Rise of Cosmopolitanism in Early Modern Europe, Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 9780812239331

- Kale, Steven (2004), French Salons: High Society and Political Sociability from the Old Regime to the Revolution of 1848, Baltimore, MD & London, England: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 9780801877292

- Konig, David Thomas (2004), "Influence and Emulation in the Constitutional Republic of Letters", Law and History Review, 22 (1): 179–182, doi:10.2307/4141670, JSTOR 4141670, S2CID 146969519

- Lambe, Patricke (1988), "Critics and Skeptics in the Seventeenth-Century Republic of Letters", The Harvard Theological Review, 81 (3): 271–296, doi:10.1017/S0017816000010105, JSTOR 1509705

- Lilti, Antoine (2005a), "Sociabilité et mondanité: Les hommes de lettres dans les salons parisiens au XVIIIe siècle" [Sociability & Mundanity: The Men of Letters in the Parisian Salons of the XVIII Century], French Historical Studies (in French), 28 (3): 415–445, doi:10.1215/00161071-28-3-415

- Lilti, Antoine (2005b), Le Monde des salons: sociabilité et mondanité à Paris au XVIIIe siècle (in French), Paris, France: Fayard, ISBN 9782213622927; published in English as The World of the Salons: Sociability and Worldliness in Eighteenth-Century Paris, translated by Cochrane, Lydia G., Oxford, England & New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 9780199772346

- Lux, David S.; Cook, Harold J. (1998), "Closed Circles or Open Networks: Communicating at a Distance during the Scientific Revolution" (PDF), History of Science, 36 (2): 179–211, doi:10.1177/007327539803600203, archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-05-08

- Maclean, Ian (March 2008), "The Medical Republic of Letters before the Thirty Years War", Intellectual History Review, 18 (1): 15–30, doi:10.1080/17496970701819327, S2CID 162244659

- Mayhew, Robert (April 2004), "British Geography's Republic of Letters: Mapping an Imagined Community, 1600–1800", Journal of the History of Ideas, 65 (2): 251–276, doi:10.1353/jhi.2004.0029, JSTOR 3654209, S2CID 143514543

- Mokyr, Joel (2017), A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy, Princeton, NJ & Oxford, England: Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691168883

- Ostrander, Gilman M. (1999), Republic of Letters: The American Intellectual Community, 1776–1865, Madison, WI: Madison House, ISBN 9780945612636

- Shelford, April G. (2007), Transforming the Republic of Letters: Pierre-Daniel Huet and European Intellectual Life, 1650–1720, Rochester, NY & Woodbridge, England: University of Rochester Press & Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 9781580462433

- Stroup, Alice (1990), A Company of Scientists: Botany, Patronage, and Community at the Seventeenth-Century Parisian Royal Academy of Sciences, Berkeley & Los Angeles, CA; London, England: University of California Press, ISBN 9780520059498, retrieved 2023-06-20

- Ultee, Maarten (1987), "The Republic of Letters: Learned Correspondence 1680–1720", The Seventeenth Century, 2 (1): 95–112, doi:10.1080/0268117X.1987.10555263