Rarotonga

NASA satellite image of Rarotonga | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Central-Southern Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 21°14′6″S 159°46′41″W / 21.23500°S 159.77806°W |

| Archipelago | Cook Islands |

| Major islands | Motutapu, Oneroa, Koromiri, Taakoka |

| Area | 67.39 km2 (26.02 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 2,139 ft (652 m) |

| Highest point | Te Manga |

| Administration | |

| Largest settlement | Avarua (pop. 4,906) |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Rarotongan |

| Population | 13,007[1] |

Rarotonga is the largest and most populous of the Cook Islands. The island is volcanic, with an area of 67.39 km2 (26.02 sq mi), and is home to almost 75% of the country's population, with 10,898 of a total population of 15,040.[2] The Cook Islands' Parliament buildings and international airport are on Rarotonga. Rarotonga is a very popular tourist destination with many resorts, hotels and motels. The chief town, Avarua, on the north coast, is the capital of the Cook Islands.

Captain John Dibbs, master of the colonial brig Endeavour, is credited as the European discoverer on 25 July 1823, while transporting the missionary Reverend John Williams.

Geography

[edit]Rarotonga is a kidney-shaped volcanic island, 32 km (20 mi) in circumference, and 11.2 km (7.0 mi) wide on its longest (east-west) axis.[3] The island is the summit of an extinct Pliocene or Pleistocene volcano, which rises 5,000 metres (16,000 feet) from the seafloor.[4] The island was formed between 2.3 to 1.6 million years ago, with a later stage of volcanism between 1.4 and 1.1 million years ago.[4] While its position is consistent with being formed by the Macdonald hotspot, its age is too young, and its formation is attributed to a short-lived Rarotonga hotspot,[5] or to rejuvenated volcanism at Aitutaki.[6]

The core of the island consists of densely forested hills cut by deep valleys, the eroded remnants of the original volcanic cone.[7] The hills are drained by a number of radial streams, including the Avatiu Stream and Takuvaine Stream.[7] Te Manga, at 658 m (2,140 ft) above sea level, is the highest peak on the island. Ikurangi, a smaller peak, overlooks the capital.

The hills are surrounded by a low coastal plain consisting of beaches, a storm ridge, lowland swamps, and alluvial deposits.[8]: 9 This in turn is surrounded by a fringing reef, which ranges from 30 to 900 metres (98 to 2,953 feet) wide.[8]: 30 The reef is shallow, with a maximum depth of 1.5 m (4.9 ft),[8]: 31 and has a number of passages, notably at Avarua, Avatiu and Ngatangiia. Beyond the reef crest, the outer reef slopes steeply to deep water.[8]: 31

The lagoon is at its widest off the southeast coast in the area of the Muri Lagoon. This area contains four small islets or motu. From north to south, the islets are:[9]

- Motutapu, 10.5 hectares (26 acres)

- Oneroa, 8.1 hectares (20 acres)

- Koromiri, 2.9 hectares (7.2 acres)

- Taakoka, 1.3 hectares (3.2 acres)

Another small islet, Motutoa, lies on the reef flat on the northwest coast.[8]: 33

Natural environment

[edit]The interior of the island is dominated by eroded volcanic peaks cloaked in dense vegetation. Paved and unpaved roads allow access to valleys but the interior of the island remains largely unpopulated due to forbidding terrain and lack of infrastructure.

Takitumu Conservation Area

[edit]A tract of 155 ha (380 acres) of land has been set aside in the south-east as the Takitumu Conservation Area to protect native birds and plants, especially the Vulnerable kakerori or Rarotonga monarch. Other threatened birds in the conservation area include the Rarotonga fruit dove and Rarotonga starling. The site has been recognised as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International.[10]

History

[edit]The earliest evidence of human presence in the Southern Cook Islands has been dated to around AD 1000. Oral tradition tells that Rarotonga was settled by various groups, including Ata-i-te-kura, Apopo-te-akatinatina and Apopo-te-ivi-roa in the ninth century, and Tangi'ia Nui from Tahiti and Karika from Samoa in 1250.[3] An early ariki, Toi, is said to have built Te Ara Nui o Toi or Ara Metua, a paved road that encircles the island, though the sites adjacent to it are dated to 1530.[11] Trading contact was maintained with the Austral Islands, Samoa and the Marquesas to import basalt that was used for making local adze heads,[12] while a pottery fragment found on Ma'uke has been traced to Tongatapu to the west, the main island of Tonga.[13] The ultimate origin of almost all the islanders’ settlement cargo can be traced back to Southeast Asia: not just their chickens, Pacific rats, Polynesian pigs, Pacific dogs and crops, but also several kinds of lizards and snails. Among the species that are understood to have reached Rarotonga by this means are at least two species of geckos and three of skinks. Likewise, the ultimate origin of almost 30 of their crops lies in the west.[14][better source needed]

According to New Zealand Māori tradition, Kupe, the discoverer of Aotearoa, visited Rarotonga, and the Māori migration canoes Tākitimu, Te Arawa, Tainui, Mātaatua, Tokomaru, Aotea, and Kurahaupō passed through on their way to Aotearoa.[3]

Fletcher Christian visited the island in 1789 on HMS Bounty but did not land.[3] Captain Theodore Walker sighted the island in 1813 on the ship Endeavour. The first recorded landing by a European was Captain Philip Goodenough with William Wentworth in 1814 on the schooner Cumberland.[15] On 25 July 1823, while transporting the missionary Reverend John Williams, the Endeavour returned to Rarotonga. Papeiha, a London Missionary Society evangelist from Bora Bora, went ashore to teach his religion.[3] Further missionaries followed, and by 1830 the island had converted to Christianity.

From 1830 to 1850, Rarotonga was a popular stop for whalers and trading schooners,[3] and trade began with the outside world. The missionaries attempted to exclude other Europeans as a bad influence, and in 1845 Rarotongan ariki prohibited the sale of land to Europeans, though they were allowed to rent land on an annual basis.[16] Despite a further ban on foreign settlement in 1848, European traders began to settle. In 1865, driven by rumours that France planned to annex the islands, the ariki of Rarotonga unsuccessfully petitioned Governor George Grey of New Zealand for British protection.[16] In 1883 the Royal navy de facto recognised the ariki of Rarotonga as an independent government.[17] By this time Makea Takau Ariki had become paramount among the ariki, and was recognised as the "Queen of Rarotonga" on a visit to New Zealand.[17] In 1888 the island became a British protectorate after a petition from the ariki.[18] In 1901, it was annexed by New Zealand.

Oranges had been introduced by the Bounty mutineers, and after annexation developed into a major export crop, though exports had been disrupted by poor shipping.[19] In 1945 the industry was revived with a government-led citrus replanting scheme,[20] and in 1961 a canning factory was opened to allow the export of juice.[21][22] The industry survived until the 1980s,[22] but collapsed after New Zealand adopted Rogernomics and removed privileged market access.[23]

An airstrip was built in 1944, leading to regular flights to Fiji, Tonga, Samoa and Aitutaki.[3] The airport and better shipping links saw the beginnings of large-scale migration to New Zealand.[24] Emigration increased further in the early 1970's when the airport was upgraded,[25] but this was balanced by immigration from elsewhere in the Cook Islands.[24]: 48–49 [26]

Flooding in April and May 1967 damaged bridges on the island and caused widespread crop losses, raising risks of a food shortage.[27] An unnamed tropical cyclone in December of that year left hundreds homeless and caused widespread devastation after demolishing homes and offices in Avarua.[28][29] In December 1976 80% of the island's banana crop was destroyed by tropical cyclone Kim.[30] In January 1987 Tropical Cyclone Sally made a thousand people homeless and damaged 80% of the buildings in Avarua.[31][32]

Demographics and settlements

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1906 | 2,441 | — |

| 1916 | 3,064 | +25.5% |

| 1926 | 3,936 | +28.5% |

| 1936 | 5,054 | +28.4% |

| 1945 | 5,573 | +10.3% |

| 1951 | 6,048 | +8.5% |

| 1961 | 8,676 | +43.5% |

| 1966 | 9,971 | +14.9% |

| 1971 | 11,478 | +15.1% |

| 1976 | 9,802 | −14.6% |

| 1981 | 9,530 | −2.8% |

| 1986 | 9,826 | +3.1% |

| 1996 | 11,225 | +14.2% |

| 2001 | 12,188 | +8.6% |

| 2006 | 13,890 | +14.0% |

| 2011 | 13,095 | −5.7% |

| 2016 | 13,007 | −0.7% |

| Source:[1] | ||

The population of Rarotonga was 13007 in 2016.[1]

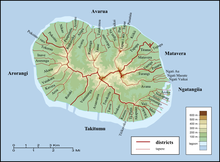

The island is traditionally divided into three tribal districts or vaka. Te Au O Tonga on the northern side of the island (Avarua is the capital), Takitumu on the eastern and southern side and Puaikura on the western side. For administrative purposes it is divided into five Land Districts. The Land District of Avarua is represented under vaka Te Au O Tonga, the Land Districts of Matavera, Ngatangiia and Titikaveka are represented under vaka Takitumu and the Land District Arorangi is represented under vaka Puaikura. The districts are subdivided into 54 tapere (traditional sub-districts).

In 2008, the three vaka councils of Rarotonga were abolished.[33][34]

Area attractions

[edit]Palm-studded white sandy beaches fringe most of the island, and there is a popular cross-island walk that connects Avatiu valley with the south side of the island. It passes the Te Rua Manga, the prominent needle-shaped rock visible from the air and some coastal areas. Hikes can also be taken to the Raemaru, or flat-top mountain. Other attractions include Wigmore Falls (Papua Falls) and the ancient marae, Arai te Tonga.

Popular island activities include snorkeling, scuba diving, bike riding, kite surfing, hiking, deep-sea fishing, boat tours, scenic flights, going to restaurants, dancing, seeing island shows, squash, tennis, zipping around on mopeds, and sleeping on the beach. There are many churches open for service on Sunday, with a cappella singing. People congregate at the sea wall that skirts the end of the airport's runway to be "jetblasted" by aircraft.[35]

Transport

[edit]

Rarotonga has three harbours, Avatiu, Avarua and Avana, of which only Avatiu harbour is of commercial significance. The Port of Avatiu serves a small fleet of inter-island and fishing vessels, with cargo ships regularly visiting from New Zealand via other Pacific Islands ports. Large cruise ships regularly visit Rarotonga but the port is too small for cruise ships to enter and they are required to anchor off shore outside the harbour. The island is encircled by a main road, Ara Tapu, that traces the coast. Three-quarters of Rarotonga is also encircled by the ancient inner road, Ara Metua. Approximately 29 km (18 mi) long, this road was constructed in 11th century and for most or all of its whole length was paved with large stone slabs. Along this road are several important marae, including Arai Te Tonga, the most sacred shrine in Rarotonga. Due to the mountainous interior, there is no road crossing the island. Rarotonga has only two bus routes: clockwise and anticlockwise.[36] The clockwise bus runs from morning operating an hourly schedule until a last service at 11pm. The anti-clockwise route leaves Avarua on the half-hour, with the last service at 4.30 pm. Although there are bus stops, the buses pick up and set down anywhere en route.

Rarotonga International Airport is the international airport of the Cook Islands.

Popular culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

- The travel writer Robert Dean Frisbie died on the island, after having lived there only briefly.

- The 1995 album Finn by the Finn Brothers ends with the song "Kiss the Road of Rarotonga", which was inspired by a motorcycle accident that Tim Finn had during a visit there.

- The U.S. television series Survivor: Cook Islands was filmed on Aitutaki, one of the islands in the southern group. One of the tribes was called Rarotonga (or Raro for short).

- A number of feature-length films are linked to Rarotonga: Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, depicting a Japanese POW camp for British prisoners in the island of Java in the year 1942, was filmed here, The Other Side of Heaven, which is set in Niuatoputapu, Tonga, but was filmed in part on Rarotonga, and Johnny Lingo which was set here.

- In the 2008 film Nim's Island, Rarotonga is portrayed as a waypoint for fictional adventure writer Alexandra Rover (Jodie Foster) on her journey from San Francisco to a South Pacific island.

- In 1951, Mexican writers Yolanda Vargas Dulché and Guillermo de la Parra wrote Rarotonga, a comic book whose plot unfolds on the island. The heroine of the story is called Zonga, an enigmatic woman with superhuman powers. The comic inspired a Mexican movie filmed in 1978 and a song by the Mexican rock band Café Tacuba.

- The 1948 film Another Shore has as its central character an Irish civil servant who fantasises about going to live on Rarotonga.

- Smooth Walker (Howard Hesseman) books a flight to Rarotonga in the 1983 film Doctor Detroit.

- Former New Zealand cricket captain John Wright's 1990 autobiography is titled Christmas in Rarotonga.[37]

Gallery

[edit]-

Te Rua Manga (The Needle) lookout

-

Te Rua Manga (The Needle)

-

Cook Islands Christian Church (CICC) in Avarua

See also

[edit]- Auparu – in Cook Islands mythology, Auparu ("gentle dew") is a stream in Rarotonga, the bathing-place of nymphs or fairies.

- Nukutere College – the country's only Roman Catholic secondary school

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Rarotonga

- Treaty of Rarotonga – 1985 South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Cook Islands 2016 Census Main Report" (PDF). Cook Islands Statistical Office. 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "2021 Census of Population and Dwellings | Cook Islands Statistics Office". Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alphons M.J. Kloosterman (1976). Discoverers Of The Cook Islands And The Names They Gave. pp. 44–47.

- ^ a b Thompson, G. M.; Malpas, J.; Smith, Ian E. M. (1998). "Volcanic geology of Rarotonga, southern Pacific Ocean". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 41 (1): 95-104. doi:10.1080/00288306.1998.9514793.

- ^ Clouard, Valérie; Bonneville, Alain (2001). "How many Pacific hotspots are fed by deep-mantle plumes?". Geology. 29 (8): 695-698. Bibcode:2001Geo....29..695C. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0695:HMPHAF>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ Jackson, M G; Halldórsson, S A; Price, a; Kurz, M D; Konter, J G; Koppers, a A P; Day, J M D (5 March 2020). "Contrasting Old and Young Volcanism from Aitutaki, Cook Islands: Implications for the Origins of the Cook–Austral Volcanic Chain". Journal of Petrology. 61 (3). doi:10.1093/petrology/egaa037.

- ^ a b B. L. Wood (1967). "Geology of the Cook Islands". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 10 (6): 1431–1434. doi:10.1080/00288306.1967.10423227. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Richmond, Bruce M (1990). "CCOP/SOPAC Technical Report 65: Coastal morphology of Rarotonga, Cook Islands". South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Collins, William T (1993). "SOPAC Technical Report 181: Bathymetry and sediments of Ngatangiia Harbour and Muri Lagoon, Rarotonga, Cook Islands" (PDF). South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Takitumu Conservation Area, Rarotonga". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ Matthew Campbell (2002). "Ritual landscape in late pre-contact Rarotonga: a brief reading". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 111 (2): 147–170. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Weisler, Marshall I.; Bolhar, Robert; Ma, Jinlong; et al. (5 July 2016). "Cook Island artifact geochemistry demonstrates spatial and temporal extent of pre-European interarchipelago voyaging in East Polynesia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (29): 8150–8155. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.8150W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1608130113. PMC 4961153. PMID 27382159.

- ^ Richard Walter; W.R. Dickinson (1989). "A ceramic sherd from Ma'uke in the Southern Cook Islands". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 98 (4): 465–470. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Crowe, Andrew (2018). Pathway of the Birds: The Voyaging Achievements of Māori and their Polynesian Ancestors. Auckland, New Zealand: Bateman. p. 122. ISBN 9781869539610.

- ^ Coppell, W. G. (1973). "About the Cook Islands. Their Nomenclature and a Systematic Statement of Early European contacts". Journal de la Société des océanistes. 29 (38): 43. doi:10.3406/jso.1973.2410. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ a b Richard Phillip Gilson (1980). Ron Crocombe (ed.). The Cook Islands, 1820–1950. Wellington: Victoria University press. pp. 41–43.

- ^ a b Gilson (1980), p. 50

- ^ "Protectorate Over the Cook's Group: The official ceremony performed". New Zealand Herald. Vol. XXV, no. 9227. 3 December 1888. p. 11. Retrieved 20 August 2020 – via Papers Past.

- ^ Johnston, W. B. (1951). "The Citrus Industry of the Cook Islands". New Zealand Geographer. 7 (2): 121-138. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7939.1951.tb01760.x.

- ^ Menzies, Brian John (1970). A study of a development scheme in a Polynesian community : the citrus replanting scheme on Atiu, Cook Islands (MA). Massey University. p. 60-62. hdl:10179/13651. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Joseph Henry Burke (1963). Australia and New Zealand: Citrus Producers and Markets in the Southern Hemisphere. U.S. Department of Agriculture. p. 38.

- ^ a b "Sweet Orange". Cook Islands Biodiversity. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Mark Scott (1991). "In search of the Cook Islands". New Zealand Geographic. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ a b Curson, Peter Hayden (1972). "COOK ISLANDERS IN TOWN" A STUDY OF COOK ISLAND URBANISATION (PDF) (PhD). University of Tasmania. p. 38-40. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Carl Walrond (8 February 2005). "Cook Islanders – Migration". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Ward, R. Gerard (1961). "A note on population movements in the Cook Islands". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 70 (1): 1-10. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ W. H. Perceval (1 July 1967). "Food shortage may follow RAROTONGA FLOODS PLAY HAVOC WITH FOOD CROPS". Pacific Islands Monthly. Vol. 38, no. 7. p. 75. Retrieved 24 July 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Hurricane lashes Cook Is. group". Canberra Times. 20 December 1967. p. 10. Retrieved 24 July 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ W. H. Perceval (1 January 1968). "Devastating hurricane lashes the Cook Islands". Pacific Islands Monthly. Vol. 39, no. 1. p. 22-23. Retrieved 24 July 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Lashes Island". Papua New Guinea Post-Courier. 15 December 1976. p. 6. Retrieved 24 July 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Sally's $35m trail". Canberra Times. 5 January 1987. p. 5. Retrieved 24 July 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Hurricane Sally, "Worst in Memory," Leaves Island Devastated". AP. 5 January 1987. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ "Cook Islands govt abolishes Rarotonga Vaka councils". 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ "Statoids: Cook Islands". Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Vaimoana Tapaleo (3 July 2015). "Tourists hurt by Air New Zealand jet blast in Rarotonga". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Bus & Taxis / Sokala Villas, Muri Beach, Rarotonga, Cook Islands

- ^ Gideon Haigh (20 December 2003). "Cricket, the Wright way". The Age. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

External links

[edit] Media related to Rarotonga at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rarotonga at Wikimedia Commons- History of districts and villages

- Original Tapere subdivision of Rarotonga