Randy Travis

Randy Travis | |

|---|---|

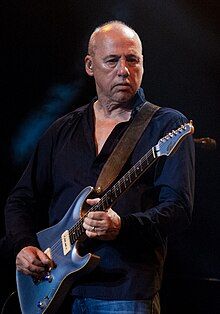

Travis performing in Bolingbrook, Illinois, in 2007 | |

| Born | Randy Bruce Traywick May 4, 1959 |

| Other names | Randy Ray |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1979–present |

| Works | |

| Spouses | Lib Hatcher

(m. 1991; div. 2010)Mary Davis (m. 2015) |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Discography | |

| Labels |

|

| Website | randytravis.com |

Randy Bruce Traywick (born May 4, 1959), known professionally as Randy Travis, is an American country and gospel music singer and songwriter, as well as a film and television actor. Active since 1979, he has recorded over 20 studio albums and charted over 50 singles on the Billboard Hot Country Songs charts, including sixteen that reached the number-one position.

Travis's commercial success began in the mid-1980s with the release of his album Storms of Life, which was certified triple-platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America. He followed up his major-label debut with a string of platinum and multi-platinum albums, but his commercial success declined throughout the 1990s. In 1997, he left Warner Bros. Records for DreamWorks Records; he signed to Word Records for a series of gospel albums beginning in 2000 before transferring back to Warner at the end of the 21st century's first decade. His musical accolades include seven Grammy Awards, eleven ACM Awards, eight Dove Awards, and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In 2016, Travis was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. Major songs of his include "On the Other Hand", "Forever and Ever, Amen", "I Told You So", "Hard Rock Bottom of Your Heart", and "Three Wooden Crosses".

He is noted as a key figure in the neotraditional country movement, a return to more traditional sounds within the genre following the country pop crossovers of the early 1980s. Nearly all of his albums were produced or co-produced by Kyle Lehning, and feature frequent co-writing credits from Paul Overstreet, Don Schlitz, and Skip Ewing. Critics have compared his baritone singing voice to other artists such as Lefty Frizzell, Merle Haggard, and George Jones. Since surviving a near-fatal stroke in 2013, which severely limited his singing and speaking ability, he has released archival recordings and made limited public appearances. James Dupré has toured singing Travis's songs with his road band. In 2024, Travis released "Where That Came From", his first studio recording since his stroke, for which his voice was re-created using artificial intelligence.

Travis's acting roles include the television movies Wind in the Wire and A Holiday to Remember, episodes of the television series Matlock, and the Patrick Swayze movie Black Dog.

Early life

[edit]Randy Bruce Traywick was born May 4, 1959, in Marshville, North Carolina.[1] He is the second of six children to Bobbie Traywick (née Tucker) and Harold Traywick.[2][3] Harold Traywick worked as a meat packer and also built houses.[4] He also enjoyed listening to country music such as Ernest Tubb and Patsy Cline, in addition to singing, playing guitar, and writing his own songs. By the time Randy was eight years old, his father would send him and his brothers to the house of a friend named Kate Magnum, who would teach him and his brothers Ricky and David how to play guitar.[5] Harold also constructed a stage behind the family house, where he would invite friends over to hear his sons sing.[6] Randy and Ricky performed publicly for the first time in 1968 at a talent show held at the local elementary school; while the brothers did not win, they continued to perform at local talent shows, with David later joining to accompany them on bass guitar.[7]

Randy dropped out of school in the ninth grade.[8] As a teenager, he committed a number of criminal offenses. These included reckless driving after he crashed Ricky's car in a cornfield, breaking into a church to hold a party, driving under the influence, resisting arrest, and stealing knives and watches from a local store.[8] On his seventeenth birthday, Randy was arrested for public intoxication and faced imprisonment.[9] Despite his charges, Don Cusic noted in the 1990 book Randy Travis: The King of the New Country Traditionalists that his parents still supported him, as they would pay his bail and support him in court whenever he was arrested.[9]

In 1977, the Traywicks entered a talent competition held in Charlotte, North Carolina, after hearing an advertisement for it on the radio. The grand prize for the contest was $100 cash and a recording session.[10] The contest consisted of eight semi-final audition rounds held every Tuesday at Country City USA, a nightclub co-owned by Randy's future wife, Mary Elizabeth "Lib" Hatcher.[10][11] At the performance, Randy played rhythm guitar and sang, while Ricky played lead guitar. However, Ricky had to drop out of the competition partway through because he had to serve time at a youth detention center, leaving Randy to continue as a solo act. Randy ended up winning the competition.[12] Afterward, he held a conversation with Hatcher about his then-impending arrest charges for hot-wiring a neighbor's truck.[13] Hatcher and disc jockey John Harper, who also worked at the club, chose to represent Randy in court, which led to him serving probation and coming under the custody of Hatcher in lieu of a jail sentence.[13][14] Additionally, Hatcher employed Randy as a singer at Country City USA.[13] During this time, Hatcher advised him on his singing and performance. Harold would attend Randy's performances in this timespan, but was later banned from the club after altercations with patrons.[15]

Music career

[edit]Hatcher booked a number of country music singers to perform at her club as a means of making connections with country music executives in Nashville, Tennessee.[16] One such singer, Joe Stampley, agreed to produce a session for Traywick in Nashville. Hatcher paid $10,000 for the recording session and promotion, which was done through an independent label based out of Shreveport, Louisiana, called Paula Records. The session accounted for the singles "She's My Woman" and "I'll Take Any Willing Woman". Traywick and Hatcher distributed copies of the single to radio stations throughout the Southern United States in 1979. The former reached number 91 on the Billboard Hot Country Songs charts.[17] After the failure of these singles, Hatcher and Traywick continued submitting demo recordings to executives but were unable to garner interest at first.[18] In 1981, Traywick and Hatcher chose to move to Nashville to put themselves closer to the center of the country music industry. Despite this, they would still travel back to Charlotte on weekends to tend to business at Country City USA, which by that point had relocated to a larger building.[19] They supported themselves by renting out part of their Nashville house to songwriter Keith Stegall, who used it as an office.[20] Stegall then introduced the two to song publisher and disc jockey Charlie Monk at a golf game, which led to him performing songs for Monk. Stegall also submitted Traywick's demos to various Nashville producers to garner interest in a recording contract. Traywick recorded one session with producer John Ragsdale for the intent of signing him to Curb Records, but the label ultimately chose not to sign him.[21]

In 1982 Hatcher began managing a nightclub called the Nashville Palace through the recommendation of singer Ray Pillow. She initially hired Traywick to wash dishes, but soon began to have him perform there as well. By this point, he began crediting himself as Randy Ray, as he and Hatcher thought the name was easier to pronounce than "Traywick".[22] Hatcher also rented her in-house office space out to other industry executives, including staff of Radio & Records magazine; meanwhile, Randy Ray continued to work on his songwriting under Stegall's mentorship.[23] By the end of the year, Hatcher and Nashville Palace owner John Hobbs financed an independent album titled Randy Ray Live at the Nashville Palace, which consisted of ten songs recorded by him at the Palace. Stegall served as producer on this project.[24] He also auditioned on You Can Be a Star, a talent show on the former Nashville Network (TNN), in early 1983. He placed second behind Lang Scott, who would later marry country singer Linda Davis.[25] Ralph Emery also invited him to perform several times on the TNN talk show Nashville Now, which he hosted.[26]

Despite the exposure from Nashville Now, he still failed to secure a recording contract throughout 1984.[26] Martha Sharp, then working in artists and repertoire (A&R) at Warner Bros. Records's Nashville division, attended a seminar in late 1984 where executives suggested signing attractive young artists with a "traditional" sound. Through mutual contacts with Monk and Stegall, she became aware of Randy Ray, who at the time was working on more songs with the latter.[27] Sharp arranged for him to be signed to a contract initially consisting of four songs. Executives disliked the name "Randy Ray" as they thought it sounded "podunk", and Sharp suggested "Randy Travis".[28]

1985–1986: Storms of Life

[edit]Travis signed with Warner Nashville in early 1985. His first contract with them resulted in the recording of four songs: "Prairie Rose", "On the Other Hand", "Carrying Fire", and "Reasons I Cheat". "Prairie Rose" appeared on the soundtrack of the 1985 film Rustlers' Rhapsody.[29] Keith Whitley also recorded "On the Other Hand" for his 1985 debut album L.A. to Miami.[30] These four songs were all recorded in the same session, with Stegall and Kyle Lehning co-producing. At the time, Lehning was best known for producing Dan Seals and had also worked with Stegall on his own singles for Epic Records. Although Lehning did not want to work with Travis at first, he chose to do so after Monk and Sharp encouraged him.[29] After recording these songs, Travis appeared on Nashville Now again on May 17, 1985, where he performed with Johnny Russell and Lorrie Morgan.[31] Warner also included him among the performers at their talent showcase at the Fan Fair (now CMA Music Festival) in downtown Nashville in mid-1985.[32] Warner released "On the Other Hand" in August 1985, and the song charted at number 67 on Hot Country Songs before falling off.[33] The follow-up "1982" peaked at number six on the country charts in early 1986,[1] thus becoming Travis's first hit single.[34] Following the success of "1982", Travis was booked as an opening act for Barbara Mandrell and T. G. Sheppard, leading to both Travis and Hatcher quitting the Palace.[35] The song's success also led to him performing on the Grand Ole Opry for the first time in March 1986.[36] He also received an award for Top New Male Vocalist from the Academy of Country Music (ACM).[37] This was followed by further opening act gigs throughout early 1986, which resulted in gigs from California to Georgia. Hatcher and Travis bought a former bread truck which they converted to a tour bus, in addition to hiring a five-piece band to perform with him.[38]

After "1982" became Travis's first top-ten hit, Warner executives chose to re-release "On the Other Hand". Nick Hunter, who promoted singles to country radio for Warner, noted that the song was popular in sales and listener demand despite its initially low chart peak. Although some radio disc jockeys considered the song "too country", it received very high requests from listeners and continued to sell strongly.[39] Upon re-release, "On the Other Hand" became his first number-one single on the Billboard country charts in July 1986.[40] "On the Other Hand" and "1982" were both included on Travis's debut album for Warner, Storms of Life.[14] The album was released on June 2, 1986, and sold over 100,000 copies in its first sales week in addition to reaching number one on Top Country Albums.[41] Six years after its release, the album was certified triple platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), honoring U.S. sales of three million copies.[42] One of the tracks, Travis's own composition "Send My Body", had previously appeared on the Randy Ray album in 1982.[43] Lehning and Stegall co-produced the album; they also contributed on keyboard and guitar, respectively. Other musicians on the project included drummers Eddie Bayers, Larrie Londin, and James Stroud; guitarist Larry Byrom; Dobro player Jerry Douglas; bassist David Hungate; and backing vocals from Lehning, Baillie & the Boys, Paul Davis, and Paul Overstreet.[44] The album produced another number-one in "Diggin' Up Bones" in late 1986, and a number two single in "No Place Like Home" in early 1987. Overstreet wrote "On the Other Hand" with Don Schlitz, "Diggin' Up Bones" with Nat Stuckey, and "No Place Like Home" by himself.[1] The latter was also Travis's first single to be promoted through a music video.[45]

In late 1986, Travis was asked to host the Country Music Association (CMA) Awards telecast to replace original host Ricky Skaggs, who had to back out after his son was hospitalized with a neck injury.[46] Travis won the Horizon Award (now called Best New Artist) at that ceremony, while also receiving a nomination for Male Vocalist of the Year. Additionally, "On the Other Hand" was nominated for Single of the Year and Storms of Life for Album of the Year.[47] On November 15, 1986, Travis performed a concert with George Jones and Patty Loveless in Charlotte, North Carolina, where Charlotte's then-mayor Harvey Gantt declared November 15 to be "Randy Travis Day". A similar acknowledgement was passed as a city ordinanace in Travis's hometown of Marshville soon afterward.[48] Warner also issued a Christmas single in December 1986 titled "White Christmas Makes Me Blue", which sold over 79,000 copies.[49] By year's end, Skaggs had inducted Travis into the Grand Ole Opry.[50] "Diggin' Up Bones" also accounted for Travis's first Grammy Award nomination, in the category of Best Male Country Vocal Performance, in early 1987.[51][52]

Storms of Life received critical favor. Mark A. Humphrey of AllMusic wrote that Travis had "astonishing Lefty Frizzell-style pipes, excellent material, and sympathetic production".[53] An uncredited review in Billboard also described Travis's voice with favor, additionally stating that " He has the material—introspective lyrics and gorgeous melodies—and the understated, classic country production here to make the most of his gifts."[54] Writing for the Chicago Tribune, Jack Hurst also compared Travis's voice favorably to both Frizzell and Merle Haggard, while also praising the lyrics of the singles in particular.[55]

1987–1988: Always & Forever

[edit]In early 1987, Travis released the single "Forever and Ever, Amen". It held the number-one position on the Billboard country charts for three weeks,[56] becoming the first song to hold that position for that long since Johnny Lee's "Lookin' for Love" in 1980.[57] The song served as the lead single to his second Warner album Always & Forever.[14] As with "On the Other Hand", Schlitz and Overstreet co-wrote the song.[1] Corresponding with this song's success, Travis won Male Vocalist of the Year from the ACM awards, where Storms of Life won Album of the Year and "On the Other Hand" won both Song and Single of the Year.[37] During the awards ceremony, Travis performed "Forever and Ever, Amen" live for the first time. Cusic described the song in 1990 as a "career record".[56] In addition to topping the country charts, "Forever and Ever, Amen" was a minor hit single in the United Kingdom, reaching number 55 on the UK Singles Chart.[58] In 2019, editors of The Tennessean listed it as one of the 100 greatest country songs of all time, while also referring to it as Travis's signature song.[59] "Forever and Ever, Amen" is also Travis's highest-certified single, having earned double-platinum RIAA certification in 2021.[42]

Always & Forever included Lehning as producer, with many of the same vocal and instrumental contributors as its predecessor such as Baillie & the Boys, Douglas, and Overstreet.[60] Lehning worked with Travis, Hatcher, and Sharp to pick from several hundred songs before determining which ones would appear on the album.[61] One track on the album was Dennis Linde's composition "What'll You Do About Me", which was previously released by Steve Earle in 1984;[62] the song would later be released by the Forester Sisters in 1992,[63] and Doug Supernaw in 1995.[64] During the promotion of the album, Travis began to notice strain on his vocal cords, which was treated through consultations at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.[65] Always & Forever spent 43 weeks at the top of the Billboard Top Country Albums charts, breaking the previous longevity record of 28 weeks set by Alabama's Mountain Music earlier in the decade.[57]

"I Won't Need You Anymore (Always and Forever)", "Too Gone Too Long", and "I Told You So" were all released as singles from Always & Forever, with all three reaching number one on the Billboard country charts between 1987 and 1988.[1] Travis wrote "I Told You So" by himself in 1982 around the time he attempted to sign with Curb Records. Monk submitted the song to Lee Greenwood at that time, although he declined it. Both Darrell Clanton and Barbara Mandrell had recorded the song,[66] the former as the B-side of his 1985 single "I Forgot That I Don't Live Here Anymore".[67] In 1996, Always & Forever received Travis's highest certification of quintuple platinum for sales of five million copies.[42]

Always & Forever and its singles accounted for several award wins and nominations for Travis. "Forever and Ever, Amen" won both Song and Single of the Year at the following year's ACM awards (honoring the year 1987), where Travis also won Top Male Vocalist. He was also nominated for Entertainer of the Year, while "Forever and Ever, Amen" received a Music Video of the Year nomination and Always & Forever was nominated for Album of the Year.[37] At the 1987 CMA Awards, Travis won Male Vocalist of the Year and was nominated for Entertainer of the Year while "Forever and Ever, Amen" won Single of the Year and was nominated for Music Video of the Year and Always & Forever won Album of the Year.[47] Additionally, Always & Forever accounted for Travis's first Grammy Award win, for Best Male Country Vocal Performance at the 30th Annual Grammy Awards in March 1988.[52] Stephen Thomas Erlewine, writing for AllMusic, thought the album "rivaled its predecessor in its quality" while also stating that it had "lean" production and "nuanced" vocals.[68]

1988–1990: Old 8×10 and No Holdin' Back

[edit]Travis continued to tour throughout the United States in 1988, including a spot on the Marlboro Country Music Tour in Madison Square Garden, which also featured Alabama, the Judds, and George Strait.[69] That same year he released his third Warner album, Old 8×10.[14] The album was originally slated to be released on July 12, but was moved up to June 30 to make it eligible for CMA Awards.[70] Nine years after its release, it was certified double-platinum.[42] The first three singles off the album all went to number one on the country charts between 1988 and early 1989. These were "Honky Tonk Moon", "Deeper Than the Holler" (another Overstreet-Schlitz collaboration), and "Is It Still Over?"[1] The fourth and final single, "Promises" (which Travis wrote with John Lindley), was much less successful with a number 17 peak on Hot Country Songs.[1] Music journalists Tom Roland and Colin Larkin both attributed the song's failure to it featuring just vocals and acoustic guitar.[71][11] Old 8×10 became his third consecutive album to reach the number one position on Top Country Albums.[72] It also won Travis a Grammy Award for Best Male Country Vocal Performance.[52] "I Told You So" received a Single of the Year nomination from the Academy of Country Music, while Travis himself was nominated as both Entertainer of the Year and Top Male Vocalist in 1988 and 1989.[37] Also in 1988, the Country Music Association awarded him as Male Vocalist of the Year a second time, along with an Entertainer of the Year nomination, as well as Single and Song of the Year nominations for "I Told You So".[47] The foundation also nominated Old 8×10 for Album of the Year alongside additional Male Vocalist and Entertainer of the Year nominations.[47] Reviewing the album for AllMusic, Brian Mansfield stated that it "lacks the monster hits of his debut but wears just as well."[73] In 1997, Old 8×10 received its highest certification of double-platinum.[42]

Travis ended 1989 with two studio albums. First was a Christmas album titled An Old Time Christmas, which included the previously-released Christmas single "White Christmas Makes Me Blue". The other tracks included a mix of Christmas standards and original songs, one of which ("How Do I Wrap My Heart Up for Christmas") Travis co-wrote with Overstreet.[74] A month later was the studio release No Holdin' Back. Prior to the album's release, Travis had recorded a cover of Brook Benton's "It's Just a Matter of Time" with producer Richard Perry for a covers album titled Rock, Rhythm & Blues. Because he liked the sound of the recording, he chose to include it on No Holdin' Back as the album's first single. The rendition reached number one on the country charts in December 1989.[71] At the 32nd Annual Grammy Awards, this rendition was nominated for Best Male Country Vocal Performance.[52] After the "It's Just a Matter of Time" cover came "Hard Rock Bottom of Your Heart". Written by Hugh Prestwood, the song held the number one position on Billboard Hot Country Songs for four weeks, accounting for Travis's longest stay at that position.[1][14] The third and final single from No Holdin' Back was "He Walked on Water", which peaked at number two.[1] The song was the first successful cut for songwriter Allen Shamblin.[75] Also included on No Holdin' Back were a cover of Marty Robbins' "Singing the Blues" and the track "Somewhere in My Broken Heart", later a single for its co-writer Billy Dean.[76][77] Thom Jurek's review for AllMusic praised Travis's vocal deliveries on "It's Just a Matter of Time" and "Hard Rock Bottom of Your Heart" while also calling Lehning's production "flawless".[77] In a review for Cash Box magazine, Kimmy Wix described "He Walked on Water" as having "detailed lyrics to which we can all relate" and thought the song was well suited for Travis's voice.[78]

1990–1992: Heroes & Friends, High Lonesome, and greatest-hits albums

[edit]Travis's first album to be released in the 1990s was Heroes & Friends, a duets album. Among the duet artists featured were Tammy Wynette, Merle Haggard, George Jones, B. B. King, and Clint Eastwood.[11] According to journalist Gary Graff, Travis had wanted to record a duet album for several years, and he and Hatcher spent over a year and a half arranging for the recording sessions.[79] The album accounted for two singles in "A Few Ole Country Boys" (a duet with Jones) and title track "Heroes and Friends" (the only track on the album not to be a duet). Both songs peaked within the top 10 of the country charts between late 1990 and early 1991.[1] Travis performed "Heroes and Friends" at the 1991 CMA Awards telecast, joined by Jones, Wynette, Vern Gosdin, and Roy Rogers.[80] Unlike his previous albums, Heroes & Friends was met with mixed reception from critics. Austin American-Statesman writer Lee Nichols thought that the album's songs were "not particularly notable, but nonetheless enjoyable".[81] Knight Ridder writer Dan DeLuca (in a review re-published in The Anniston Star) praised the duets with Haggard and Jones, and considered the duet version of Dolly Parton's "Do I Ever Cross Your Mind" to be the strongest track, although he also panned the contributions of King and Eastwood.[82] In a review for Entertainment Weekly, Alanna Nash thought that "[t]he guests show up more to bolster Travis's profile than to actually perform full-out", although she praised Loretta Lynn's duet vocals on "Shopping for Dresses".[83] Despite the mixed reception, Heroes & Friends certified platinum in 1991.[42] Travis also noted that 1990 was the first year in which he did not receive any ACM or CMA awards, but that he was still receiving significant radio airplay and sales, and positive feedback from fans in concert.[79] Relatedly, Mansfield and Colin Larkin both observed that in the early 1990s, Travis's success began to diminish as newer artists such as Clint Black and Garth Brooks grew in popularity.[14][11]

Travis's next studio album was 1991's High Lonesome, led off by the single "Point of Light".[1] George H. W. Bush, then President of the United States, commissioned Schlitz and Thom Schuyler to write the song as a tie-in to his "thousand points of light" campaign for volunteerism.[84] Because of its inspiration, Travis noted that journalists often asked him about political matters, and he refused to answer them as he did not think the song itself was political.[85] He also performed the song for a number of events intended to honor American soldiers returning from Operation Desert Storm.[86] Next from High Lonesome was Travis's twelfth number-one, "Forever Together",[1] one of several songs he wrote with Alan Jackson while the two were on tour together in 1991.[87] These collaborations also produced the album's next two singles "Better Class of Losers" and "I'd Surrender All" between late 1991 and early 1992, as well as Jackson's number one single "She's Got the Rhythm (And I Got the Blues)" later in 1992.[88] Jackson also co-wrote the track "Allergic to the Blues", while Travis wrote "I'm Gonna Have a Little Talk" (featuring backing vocals from gospel group Take 6[89]) and "Oh, What a Time to Be Me". Travis said that he wrote more songs for the album than previous ones.[87] Jurek praised the Jackson co-writes in particular, highlighting their lyrics and vocal deliveries in his review for AllMusic.[89] Nash also praised the lyrics on the songs co-written by Jackson, while also stating that Travis "never sounded so relaxed or so confident".[90]

Later the same year, Warner released a pair of greatest hits albums: Greatest Hits, Volume One and Greatest Hits, Volume Two. In addition to featuring most of his hit singles to this point, the projects also included four new tracks and the album cut "Reasons I Cheat" from Storms of Life.[91] Among the new tracks, "If I Didn't Have You" and "Look Heart, No Hands" both went to number one upon release as singles that year. Skip Ewing and Max D. Barnes wrote the former, while Trey Bruce and Russell Smith wrote the latter.[1] Despite these songs' successes on radio, their follow-up "An Old Pair of Shoes" reached number 21 upon release in early 1993.[1] Both greatest-hits albums certified platinum in 1995.[42]

1992–1995: Wind in the Wire and This Is Me

[edit]Travis took a hiatus from touring in 1992 and 1993, citing exhaustion as the reason for doing so.[92] He and Hatcher chose to spend time at a property in Maui they had acquired. According to Travis, the touring hiatus caused some fans and news reporters to believe he had retired,[93] so he asked his publicists to put out press releases indicating he was "merely taking a break".[94] During the hiatus, he released an album of Western music titled Wind in the Wire, a tie-in to a television movie of the same name in which he starred.[14] The album was produced by session guitarist Steve Gibson, making it his first since the Randy Ray album not to be produced by Kyle Lehning.[95] It was commercially unsuccessful, with none of its singles reaching top 40 on the Billboard charts.[14] However, lead single "Cowboy Boogie" reached number 10 on the Canadian country music charts then published by RPM.[96] Travis and one of his managers later attributed the album's commercial failure to its Western swing sound proving unpopular with radio.[93]

In late 1993, Travis began working on a follow-up album with Lehning when he was contacted by a representative for the then-under construction MGM Grand Las Vegas in Las Vegas, Nevada. The representative wanted Travis to be the first country artist to perform at the new venue once it opened, which inspired Travis to begin touring again. He and Hatcher joined with Jeff Davis, another former manager of Travis's who was then working with Brother Phelps, to assemble a backing band for the Las Vegas shows, which included Lehning as keyboardist.[97] The Las Vegas shows, held in early 1994, were his first concerts in over 14 months.[93] Due to the success of these shows, Travis resumed his touring schedule soon afterward. He re-established his existing touring band and performed at a showcase of Warner Bros. artists held in Nashville during the Country Radio Seminar, an annual promotional concert series held by Country Radio Broadcasters.[98][93] At the same time, Travis continued writing and compiling songs for his next studio album. "Before You Kill Us All" was released on February 28, 1994,[93] as the lead single to his next Warner album This Is Me.[14] The song peaked at number two on the Billboard country charts.[1] Travis and Lehning chose the song because the two wanted "story songs and some with a wink of humor".[99] Similarly, he told Billboard in 1994 that the song was an example of a more modern and "rowdy" sound he wanted to achieve relative to his prior albums.[93] It was followed later in the year by "Whisper My Name", his fifteenth number-one on Billboard.[1] The album's title track and "The Box" were both top-ten hits between late 1994 and early 1995 as well.[1] Travis wrote "The Box" with Buck Moore and later said he became emotional writing and performing the song, as its theme of a father struggling to express love to his children reminded him of his own "fractured" relationship with his father.[99]

Bob Saporiti, then an executive at Warner Bros. Nashville, noted that the failure of Wind in the Wire and length of time since High Lonesome had created "angst" among label executives, but added that they considered This Is Me "back to the basics".[93] To promote the album, Travis hosted an episode of the TNN talk show Music City Tonight; the network also re-aired the Country Radio Seminar concert.[93] Jurek praised the lyrical contributions of Trey Bruce, Larry Gatlin, and Kieran Kane, and considered "Whisper My Name" to be "among the greatest songs Travis has ever recorded".[100] Nash thought that the lyrics of the singles were among Travis's strongest, also stating that the album had "zippier instrumental touches" than his 1980s albums.[101] Additionally, Larkin stated that the album was "as strong as ever".[11] By mid-1994, This Is Me was certified gold by the RIAA.[42] Despite spending most of 1995 without a charted single,[1] Travis continued to tour throughout the year alongside Sammy Kershaw and George Jones.[102]

1996–1997: Full Circle

[edit]

Travis's final album for Warner was Full Circle in 1996.[14] Travis told Billboard prior to its release that he and Lehning spent over a year selecting songs for the album because they wanted to be sure they were fully satisfied with its content.[103] Its lead single was "Are We in Trouble Now", a song written by Mark Knopfler. Both this song and follow-up "Would I" failed to reach the top 20 on the country charts, while neither "Price to Pay" nor a cover of Roger Miller's "King of the Road" (which also appeared on the soundtrack of the 1997 movie Traveller[104]) made top 40.[1] Richmond Times-Dispatch writer Gordon Ely noted the failure of the album's lead single and questioned whether the album and Travis in general could still be successful in the long term, due to an influx of younger artists in the intervening years.[105] Ely considered the album "strong as ever", with a focus on Lehning's production and Travis's voice, as well as the lyrics of "Price to Pay".[105] Country Standard Time writer Don Yates found the influence of honky-tonk in certain songs and praised the lyrics and vocal delivery of "Are We in Trouble Now", but criticized "Would I" as "gimmicky" and closing track "Ants on a Log" as "trite".[106] AllMusic writer Thom Owens said of Full Circle, "his mid-'90s albums suffered from a tendency to sound a bit too similar to each other. Full Circle solves that problem by simultaneously reaching back into his hardcore honky-tonk roots and moving toward more contemporary material".[107]

In mid-1997, Travis announced that he had departed from Warner Bros. due to disagreements over the promotion of Full Circle, as well as concerns that the country music industry was beginning to move toward back country pop influences.[108] Travis also observed at the time that Warner executives were not letting him, Lehning, and Hatcher have as much liberty on selecting singles as they had on previous albums.[109] At the time of his departure from Warner, Travis was offered contracts by the Nashville divisions of both Asylum Records and the then-new DreamWorks Records.[108] Lehning had just become president of Asylum Records's Nashville division at the time, but Travis chose not to follow him to that label as he did not think Lehning's position was long-term.[110]

1997–1999: DreamWorks Records

[edit]By August 1997, Travis had become the first artist signed to DreamWorks Records's Nashville division.[111] The new label's president was musician and producer James Stroud, whom Travis knew because he had played drums on some of his earlier singles such as "Forever and Ever, Amen".[112] Because Lehning's duties as president of Asylum left him temporarily unavailable as a producer, Stroud and Byron Gallimore (best known for his work with Tim McGraw) produced Travis's music for DreamWorks.[110] Travis's late-1997 single "Out of My Bones" was the first release for DreamWorks Nashville.[113] Co-written by Gary Burr and Sharon Vaughn, it peaked at number two on the country charts in early 1998.[1] It appeared on his first DreamWorks album You and You Alone, issued in April.[14] The project also accounted for the top-ten hits "The Hole" and "Spirit of a Boy, Wisdom of a Man" and the top-20 "Stranger in My Mirror". Both "The Hole" and "Stranger in My Mirror" were co-written by Skip Ewing.[1] "Spirit of a Boy, Wisdom of a Man" was previously recorded by Mark Collie on his 1995 album Tennessee Plates.[114] Jeffrey B. Remz of Country Standard Time criticized the heavy drums on "I Did My Part", but otherwise praised the use of acoustic instruments and the strength of Travis's voice.[115] Lincoln Journal Star writer L. Kent Wolgamott noted the presence of fiddle and steel guitar in the production while also calling Travis's voice "expressive".[116]

In 1999, Travis was one of several artists on the collaborative song "Same Old Train", featured on the multi-artist album Tribute to Tradition. Other acts appearing on the song included Clint Black, Dwight Yoakam, Pam Tillis, and Marty Stuart, the last of whom also wrote and produced it.[117] The track won a Grammy Award for Best Country Collaboration with Vocals for all artists involved.[52] Travis's second and final DreamWorks album A Man Ain't Made of Stone also came out in 1999.[14] The title track (also co-written by Burr) was a top-20 country hit by year's end, but the other singles—"Where Can I Surrender", "A Little Left of Center", and "I'll Be Right Here Loving You"—all failed to reach top 40.[1] Gallimore and Stroud recorded the album largely in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where Travis and Hatcher had a house at the time.[118] Following the failure of the album's singles, Travis exited DreamWorks Records in October 2000.[119] Shortly after his departure, Travis told Country Standard Time that he chose to leave DreamWorks because he felt the label was not properly distributing the album to stores. He also thought that Stroud's production style put too much emphasis on the instrumentation instead of his singing voice.[120]

2000–2003: Switch to gospel and "Three Wooden Crosses"

[edit]

While he was still on Warner, Travis had begun working with Lehning on a gospel music album.[121][122] Other than a cover of "Amazing Grace", the two intentionally sought to include original content. Travis finished the tracks at a time when he was not on a record label. Through a connection Lehning had with Word Records executive Barry Landis, Travis was signed to that label in late 2000 and released the gospel album, by then titled Inspirational Journey.[123] Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter provided guest vocals on the track "The Carpenter".[121] Kenny Chesney sang duet vocals on the track "Baptism" (also titled "Down with the Old Man (Up with the New)"), which served as the first single. The two had previously recorded the track on Chesney's 1999 album Everywhere We Go.[120] The project won Travis two Dove Awards in 2001: Bluegrass Album of the Year for the album itself, and Country Recorded Song of the Year for "Baptism".[124] AllMusic reviewer Todd Everett found influences of bluegrass, Don Williams, and Lefty Frizzell, and found it consistent with Travis's 1980s and 1990s albums in tone.[121] Alanna Nash of Entertainment Weekly was less favorable, as she thought that the album had strong opening tracks but added that "midway, it deteriorates into Nashville formula, with simplistic homilies [and] overblown production".[125]

Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, Travis co-wrote and released a promotional patriotic single titled "America Will Always Stand".[126] Proceeds from sales of the single were donated to the American Red Cross.[127] He continued to record on Word Records as a gospel artist and put out his next album for the label, Rise and Shine, in late 2002. The album's lead single was "Three Wooden Crosses". According to Travis, Kim Williams and Doug Johnson had provided the song to Michael Peterson, who at the time was recording songs with Lehning. Peterson suggested Lehning take the song to Travis, for whom he thought it was better suited.[128] By early 2003, "Three Wooden Crosses" became Travis's sixteenth and final number-one on Billboard Hot Country Songs. It also accounted for his highest solo peak on the Billboard Hot 100 at number 31. The project accounted for only one other single in "Pray for the Fish", which fell below top 40 on the country charts.[1] Robert L. Doerschuk of AllMusic called the album "a strong performance, presented with flawless studio clarity and persuasive, understated feeling."[129] Remz noted the consistency of Lehning's production and Travis's voice, as well as the presence of original songs co-written by Travis.[130] In October 2003, Rise and Shine was certified gold.[42] At the 2004 Grammy Awards, Rise and Shine won a Grammy Award for Best Southern, Country or Bluegrass Gospel Album, while "Three Wooden Crosses" was nominated for Best Male Country Vocal Performance.[52] In 2004, "Pray for the Fish" won a Dove Award for Country Recorded Song of the Year.[124]

2003–2007: Continued gospel albums

[edit]His next gospel album was 2003's Worship & Faith. Unlike the previous projects, it included 20 acoustic covers of existing praise songs and hymns.[131] Among the tracks included were "In the Garden", "How Great Thou Art", "Peace in the Valley", and "I'll Fly Away". Jurek called the album "direct, unfiltered, hard-line gospel at its best, by a master" in a review for AllMusic.[132] Worship & Faith also became a gold album,[42] and accounted for his second consecutive Grammy Award for Best Southern, Country or Bluegrass Gospel Album.[52] A year later he released Passing Through.[14] This album accounted for his last solo chart singles until 2024, "Four Walls" and "Angels".[128] The latter was Travis's 50th entry on the chart.[1] Co-writers on the album included Jamie O'Hara, Dennis Linde, Sharon Vaughn, and Travis.[133] "Four Walls" was previously cut by Keith Harling,[134] while the album track "That Was Us" was previously recorded by both Tracy Lawrence and Chad Brock, whose version was a single in 2003.[135][133][136] Erlewine wrote of Passing Through, "It's inspirational music in the purest sense—it doesn't preach, it instructs and inspires through its carefully observed tales."[133] Travis received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in September 2004.[137]

In 2005, Travis released another gospel album, Glory Train: Songs of Faith, Worship, and Praise.[14] It, too, won a Grammy Award for Best Southern, Country or Bluegrass Gospel Album.[52] Some tracks on the project included backing vocals from the Blind Boys of Alabama. Unlike the previous albums, it contained a mix of Black spirituals and contemporary Christian music such as Darlene Zschech's "Shout to the Lord". Erlewine thought the inclusion of such material made it "Travis's best gospel album to date".[138] Writing for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Nick Marino praised Travis's "bluesy" vocals and the variety of songs.[139] Altogether, Travis's first four gospel albums each won the Dove Award for Country Album of the Year, accounting for a streak of four consecutive wins in that category from 2003 to 2006.[124] Also in 2006, Travis began recording footage for a Christmas DVD titled Christmas on the Pecos. This footage consisted of him singing Christmas songs and reading Helen Steiner Rice's poem "The Christmas Guest" inside the Big Room, a cavern at Carlsbad Caverns National Park.[140] Some of the performances also included vocal accompaniment from the choir of the Carlsbad First Baptist Church. The DVD was released in late 2006.[141] Another Christmas project, the album Songs of the Season, followed in 2007.[142]

2008–2011: Return to Warner and Carrie Underwood version of "I Told You So"

[edit]In 2008, he released his next studio album Around the Bend.[14] The project was his first country music release since A Man Ain't Made of Stone.[143][144] The album also placed him back on Warner, which had been a distributor of his Word Records releases.[145] Travis promoted the album in an interview with WSM-FM radio host Bill Cody.[143] He also released its lead single "Faith in You" as a free download from his website.[146] "Dig Two Graves" was the project's second single.[144] In addition to these songs, the album included a cover of Bob Dylan's "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right".[143] Jeff DeDekker of The Leader-Post noted that while it was not marketed as a Christian album, individual songs still held themes of "redemption and the afterlife".[144] He praised the lyrics of "Dig Two Graves" and Travis's singing voice in particular.[144] Erlewine criticized the use of a string section on "Faith in You", but otherwise reviewed the album's song selection and Travis's voice with favor.[147] Despite not being explicitly marketed as a Christian album, it won Travis his eighth and final Dove Award, in the category of Country Album of the Year.[124]

Carrie Underwood recorded a cover of "I Told You So" on her late-2007 album Carnival Ride.[148] Her version was released in January 2009 as the album's fifth single. Two months after her rendition was released to radio, disc jockey Jesse Tack at WUBE-FM in Cincinnati, Ohio combined Underwood's recording with the vocal track from Travis's original and distributed the results to 75 other radio stations. Due to the popularity of the combined recording with radio listeners, Underwood and Travis performed the song together on American Idol soon after.[149] The two also recorded an official duet version, which was sent to radio as well.[150] With both Travis and Underwood receiving chart credit, the duet version of "I Told You So" peaked at number two on the country charts in 2009, and accounted for Travis's highest overall Billboard Hot 100 peak of number nine.[151] The duet won both artists the 2010 Grammy Award for Best Country Collaboration with Vocals.[52]

Travis continued to record for Warner at the time. To honor the 25th anniversary of Storms of Life, he released Anniversary Celebration in 2011.[14] The album consisted entirely of collaborations, on both re-recordings of Travis's previous singles and new songs.[152] Among the artists involved were Zac Brown Band ("Forever and Ever, Amen"), Kenny Chesney ("He Walked on Water"), Jamey Johnson ("A Few Ole Country Boys"). Alan Jackson contributed to a medley of Travis's "Better Class of Losers" and Jackson's "She's Got the Rhythm (And I Got the Blues)", both of which the two co-wrote. George Jones, Lorrie Morgan, Ray Price, Connie Smith, Joe Stampley, and Gene Watson all provided vocals to the track "Didn't We Shine". Karlie Justus of Country Standard Time highlighted these tracks in particular among the strongest.[153] Next on Warner was 2013's Influence Vol. 1: The Man I Am, consisting of cover songs such as Lefty Frizzell's "Saginaw, Michigan", Ernest Tubb's "Thanks a Lot", and George Jones's "Why Baby Why". The only track on the album not to be a cover was "Tonight I'm Playin' Possum", a duet with Joe Nichols. Remz noted that many of the cover songs chosen were written or performed by Merle Haggard, and spoke favorably of Lehning's "low-key" production.[154]

2013–present: Career after stroke

[edit]In July 2013, Travis experienced difficulty breathing while working out at his home gym.[155] He was hospitalized in Dallas, Texas, for viral cardiomyopathy. While undergoing treatment, Travis suffered congestive heart failure and a stroke.[156][157][158] The stroke affected the left side of Travis's brain, impacting movement on the right side of his body. Travis was placed on life support after the infection caused his lungs to collapse, and was declared to have a one percent chance of survival.[158] The infection, subsequent stroke, and three separate bouts of pneumonia led to Travis undergoing three tracheostomies and two brain surgeries.[158] He also suffered aphasia, lost the ability to speak and sing, and had vision problems. These issues were mitigated through years of therapy with Davis, to whom he was engaged at the time.[158] While the stroke removed most of Travis's ability to sing, he has made sporadic onstage appearances and to perform in a limited capacity. By November 2014, Travis was beginning to recover, could walk short distances without assistance, and was relearning to write and to play guitar.[159] He also continued releasing songs recorded prior to the stroke, starting in 2014 with Influence Vol. 2: The Man I Am.[14][160] In 2015, he made a guest appearance at the Academy of Country Music awards ceremony, where Lee Brice paid tribute to him by singing "Forever and Ever, Amen".[161]

In 2016, Travis was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame, and sang "Amazing Grace" at the induction ceremony.[155][162][163] The same year, he appeared in the music video for "Forever Country", a multi-artist medley of "Take Me Home, Country Roads", "On the Road Again", and "I Will Always Love You" done to honor the 50th anniversary of the Country Music Association.[164] Although he had begun appearing in public again at this point, his speech remained limited and he was confined to a wheelchair.[155] Despite the limitations, Travis appeared onstage with singer Michael Ray during a cover performance of "Forever and Ever, Amen" in June 2017.[165] He did the same during his 60th birthday party, hosted by the Grand Ole Opry on May 4, 2019.[166]

In September 2019, Travis announced his return to touring. The tour features James Dupré as lead vocalist singing with Travis's backing band.[167] Travis selected Dupré after seeing him perform on The Voice. During these shows, Travis makes selected appearances throughout, which include singing the final "Amen" at the end of "Forever and Ever, Amen".[168] Announced as a twelve-city tour, the first performances with Dupré cut back to three concerts shortly before the tour began in October "due to unexpected production and technical issues related to the elaborate content of the show," with the intent to reschedule the canceled shows after the technical problems were resolved.[169][170] As of 2024, Dupré still tours in this capacity alongside Travis.[171]

Travis released Precious Memories (Worship & Faith) through Bill Gaither's Music label in February 2020. The project contains 12 songs that were recorded in 2003 at the Calvary Assembly of God Church in Orlando, Florida.[172] This was followed four months later by a new single titled "Fool's Love Affair", consisting of a demo recording he had done in the early 1980s.[173] In April 2024, Travis posted to TikTok a clip of a new song titled "Where That Came From", his first new studio recording since the stroke. The song was released to country radio soon afterward.[174][175] CBS News correspondence revealed that Lehning created the song through voice cloning technology, wherein he used an artificial intelligence program to re-create Travis's voice.[176] The program was trained on 42 recordings of Travis's voice as well as the voice of Dupré.[177]

Musical style

[edit]Travis is noted as a key figure in the neotraditional country movement, a shift in mainstream country music sound toward a more traditional style after the country pop crossovers of the early 1980s. Brian Mansfield wrote in AllMusic that "At a time when most were still pursuing the pop-oriented sound of the Urban Cowboy craze, Travis's strong, honest vocal style and relatable songs of everyday life helped launch the New Traditionalist movement".[14] In the Virgin Encyclopedia of Country Music, Colin Larkin wrote that Travis "was the first modern performer to demonstrate that country music could appeal to a wider public, and perhaps Garth Brooks owes him a debt."[11] Alanna Nash similarly stated that Travis was a "standard bearer" for the genre's shift toward neotraditional country through later acts such as Brooks and Clint Black, whom she stated "immediately began to surpass Travis at the awards shows and in record stores."[90] Regarding his physical appearance, Gary Graff stated that "his hunkish, weight-pumping good looks have established a physical sexuality that had been missing from many of country's male stars."[79]

Writing for AllMusic, Mansfield found influences of Merle Haggard and George Jones in Travis's singing voice,[14] and Mark A. Humphrey compared his voice to Lefty Frizzell on the same site.[53] Nash called his voice a "glass-rattling baritone".[90] Cusic found influences of Waylon Jennings and Ernest Tubb in tracks from Storms of Life, highlighting conventionally country lyrical themes of "lost love" in "1982" and infidelity in "Reasons I Cheat".[43] Critics have also noted Lehning's long-time role as Travis's producer, with Jurek stating in a review of High Lonesome that the "production is unobtrusive and clean, setting Travis in perfect balance with a band that feels live."[89] In a review for Country Standard Time, Karlie Justus referred to Travis as having a "trademark baritone" and "steel [guitar]-laced, storytelling catalog."[153] Robert L. Doerschuk said that Travis has a "familiar unforced, relaxed style".[129] Reviewing You and You Alone, Jeffrey B. Remz wrote that "He generally remains tried and true to his roots dishing out ballads with his usual great vocal phrasing...Travis doesn't rush through the songs, delivering them in a passionate, understated singing style".[115] Of his shift to gospel music at the beginning of the 21st century, Erlewine wrote that such albums were "fruitful, producing a series of good, heartfelt records, yet they also had a nice side effect of putting commercialism way on the back burner, as the gospel albums were made without the charts in mind".[147]

Travis has been cited as an influence on later generations of singers. Travis and Hatcher booked Daryle Singletary as an opening act and member of their touring band after hearing his vocals on the demo of "An Old Pair of Shoes", and he would often join Travis in this capacity to sing "It's Just a Matter of Time". After Singletary signed a recording contract with Giant Records in 1995, Travis co-produced Singletary's self-titled debut album.[178] Nash referred to Singletary as a "protégé" of Travis's with a "sonorous baritone".[179] Josh Turner cites Travis as an influence, and said that "Diggin' Up Bones" was the first song he performed in public. The two collaborated in 2006 on the show CMT Cross Country.[180] Travis contributed a guest vocal to Turner's cover of "Forever and Ever, Amen" on his 2020 covers album Country State of Mind.[181] Turner and Chris Janson both cited "Diggin' Up Bones" as an influence when interviewed for a 2017 tribute concert.[182] Justus also noted Turner as a successor to Travis in a review of Anniversary Celebration, where she also thought the themes of musical aspiration in "A Few Ole Country Boys", originally a duet with George Jones, were a "full circle moment" when Travis sang the same song with Jamey Johnson.[153]

Acting

[edit]Travis made his acting debut in 1988, making an uncredited cameo in the Emilio Estevez movie Young Guns. Although most of his part was cut from the final movie, he sang the title track to the movie's soundtrack.[65] He began acting on television in the early 1990s when he was cast as a house painter in an episode of Matlock.[80] A year later he starred in the television movie Wind in the Wire which aired on ABC. Travis's 1993 album of the same name was a soundtrack to this film.[183] Travis's acting roles would continue into the mid-1990s with such films as Frank and Jesse and Maverick.[184] In late 1995, he and Rue McClanahan starred in the CBS television movie A Holiday to Remember. Before the movie's release, Travis stated that the appearance on Matlock earlier in the decade was what inspired him to take on more acting roles, and that A Holiday to Remember was one of his first roles not related to the Western genre.[185] Coinciding with the release of You and You Alone, Travis starred alongside Patrick Swayze in the film Black Dog, playing the role of a country music singer.[186] In turn, Swayze contributed backing vocals to the track "I Did My Part" on You and You Alone.[116] In February 2024, Travis appeared as a special guest on an episode of the game show The Price Is Right.[187]

Personal life

[edit]Travis and Hatcher lived together for several years at early points in their career.[188] The couple secretly married on May 31, 1991 and bought a house on Maui soon afterward.[189] Because of the secrecy of their marriage and the relocation to Maui, Travis later noted that many fans theorized he was gay and had contracted HIV/AIDS.[189] In early 1991, the tabloid National Enquirer ran an article alleging that Travis was gay. In response, Travis considered suing the publication until a lawyer convinced him otherwise.[189][190] Journalist Michael Corcoran noted that their marriage was seen as controversial at first, due both to its initial secrecy and the fact that Hatcher was 18 years older than Travis.[189] Travis and Hatcher divorced in October 2010, citing incompatibility. Despite this, Hatcher continued to serve as his manager at the time.[191] After a period of engagement, he married Mary Davis on March 21, 2015.[162][161] The couple reside at Chrysalis Ranch, a property they own near Tioga, Texas.[162][192] Davis tended to Travis's medical needs during his stroke in 2013, and has made public appearances on his behalf to compensate for his limited speech.[162]

Several incidents in which the singer became publicly intoxicated were reported in the early 2010s. Travis was arrested in February 2012, when he was found in a parked car outside a church in Sanger, Texas, with an open bottle of wine and smelling of alcohol.[193] On August 7, 2012, state troopers in Grayson County, Texas, responded to a call that an unclothed man was lying in the road. Troopers reported that they arrived to find Travis unclothed and smelling of alcohol.[194] The Texas Highway Patrol said that Travis crashed his car in a construction zone, and that when they attempted to apprehend him, the singer threatened their lives. Travis was subsequently arrested for driving under the influence and making terroristic threats against a public servant. He posted bail in the amount of $21,500.[195] Earlier in the same evening, just prior to the DUI arrest, Travis allegedly walked into a Tiger Mart convenience store naked, demanding cigarettes from the cashier, who in turn called the authorities. According to the store clerk, Travis left the store upon realizing he did not have any money to pay for the cigarettes.[196] Travis filed a lawsuit to block the release of police dashcam video of the incident. After a five-year legal battle, a judge ruled that the video did not violate his right to privacy; it was released to the public in December 2017.[197]

Awards

[edit]Travis has won seven Grammy Awards, six CMA Awards, and eleven ACM awards.[52][37][47]

Discography

[edit]- Studio albums

- Storms of Life (1986)

- Always & Forever (1987)

- Old 8×10 (1988)

- No Holdin' Back (1989)

- An Old Time Christmas (1989)

- Heroes & Friends (1990)

- High Lonesome (1991)

- Wind in the Wire (1993)

- This Is Me (1994)

- Full Circle (1996)

- You and You Alone (1998)

- A Man Ain't Made of Stone (1999)

- Inspirational Journey (2000)

- Rise and Shine (2002)

- Worship & Faith (2003)

- Passing Through (2004)

- Glory Train: Songs of Faith, Worship, and Praise (2005)

- Songs of the Season (2007)

- Around the Bend (2008)

- Anniversary Celebration (2011)

- Influence Vol. 1: The Man I Am (2013)

- Influence Vol. 2: The Man I Am (2014)

- Precious Memories (Worship & Faith) (2020)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Whitburn 2017, pp. 365–366.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 1–3, 8, 9.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 8, 9.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 12.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 13.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b Cusic 1990, pp. 18.

- ^ a b Cusic 1990, p. 19.

- ^ a b Cusic 1990, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f Colin Larkin (1998). The Virgin Encyclopdia of Country Music. Virgin Books. pp. 427–428.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b c Cusic 1990, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Brian Mansfield. "Randy Travis biography". AllMusic. Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 30.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 31.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 29, 40.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 39, 41.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 54.

- ^ a b Cusic 1990, pp. 63, 64.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 72.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Cusic 1990, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Al Campbell. "L.A. to Miami". AllMusic. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 77.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 81.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 86.

- ^ a b c d e "Search results for Randy Travis". Academy of Country Music. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 93.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 97.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 97–99.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Search results for Randy Travis". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ a b Cusic 1990, p. 99.

- ^ Storms of Life (CD booklet). Randy Travis. Warner Bros. Records. 1986. 9 25435-2.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b c d e "Search results for Randy Travis". Country Music Association. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 112.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 114.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 115.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Randy Travis artist page". Grammy Awards. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ a b Mark A. Humphrey. "Storms of Life review". AllMusic. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ "Reviews" (PDF). Billboard. June 14, 1986. p. 72.

- ^ "In review". Chicago Tribune. August 24, 1986. pp. 22, 23. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Cusic 1990, p. 122.

- ^ a b Roland 1991, p. 490.

- ^ "The Official Charts Company - Randy Travis". Official Charts Company. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ Matthew Leimkuehler; Dave Paulson; Cindy Watts (August 25, 2019). "What are the all-time greatest country songs? These 100 top our list". The Tennessean. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ Always & Forever (CD booklet). Randy Travis. Warner Bros. Records. 1987. 9 25568-2.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Cusic 1990, p. 124.

- ^ McGee, David (2005). Steve Earle: Fearless Heart, Outlaw Poet. CMP Media. p. 69. ISBN 9780879308421.

- ^ Whitburn 2017, p. 130.

- ^ Whitburn 2017, p. 353.

- ^ a b Cusic 1990, p. 125.

- ^ Cusic 1990, pp. 42, 43, 63, 81.

- ^ Whitburn 2017, p. 83.

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "Always & Forever review". AllMusic. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 150.

- ^ Cusic 1990, p. 152.

- ^ a b Roland 1991, pp. 569–570.

- ^ "Randy Travis Album & Song Chart History - Country Albums". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ Brian Mansfield. "Old 8×10". AllMusic. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ "An Old Time Christmas". AllMusic. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ Thomas Goldsmith (June 15, 1990). "Writer uses nostalgia for Travis hit". The Tennessean. pp. 1D. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Whitburn 2017, p. 105.

- ^ a b Thom Jurek. "No Holdin' Back". AllMusic. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ Kimmy Wix (May 12, 1990). "Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box: 24.

- ^ a b c Gary Graff (November 7, 1990). "Randy Travis gets fans, if not awards". Daily Press. pp. C4. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 123.

- ^ Lee Nichols (November 22, 1990). "Randy Travis pays tribute with 'Heroes & Friends'". Austin American-Statesman. p. 23. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ "'Heroes & Friends' pairs Randy Travis with country music legends". The Anniston Star. October 6, 1990. p. 9. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Alanna Nash (December 12, 1990). "Notable country album releases". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 115.

- ^ Jack Hurst (February 16, 1992). "Travis in his prime". Chicago Tribune. p. 11. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, pp. 115–116.

- ^ a b "Travis returns to roots". San Bernardino County Sun. September 26, 1991. pp. D1. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 124.

- ^ a b c Thom Jurek. "High Lonesome". AllMusic. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b c Alanna Nash (August 30, 1991). "High Lonesome review". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Susan Beyer (October 31, 1992). "Travis collection guaranteed to be around for a long time". The Ottawa Citizen. pp. H3. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jim Bessman (April 13, 1994). "New Warner set returns Travis to country spotlite". Billboard. pp. 14, 127. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 127.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 130.

- ^ "RPM 100 Country Tracks". RPM. October 30, 1993. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 131-132.

- ^ a b Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 133.

- ^ Thom Jurek. "This Is Me". AllMusic. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ "This Is Me review". Entertainment Weekly. April 29, 1994. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 135.

- ^ Deborah Evans Price (July 6, 1996). "Randy Travis comes 'Full Circle'". Billboard. pp. 27, 29.

- ^ "Traveller soundtrack". AllMusic. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Gordon Ely (September 15, 1996). "So has Randy Travis fallen victim to ol' boy syndrome?". Richmond Times-Dispatch. pp. J8. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Don Yates. "Full Circle review". Country Standard Time. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Thom Owens. "Full Circle". AllMusic. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Mel Shields (August 10, 1997). "Randy Travis travels 'Full Circle' with new album". The Sacramento Bee. p. 25. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 142.

- ^ a b Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 143.

- ^ Will Pinkston (August 28, 1997). "Singer's going Hollywood". The Tennessean. pp. 1A. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 142, 135-136.

- ^ Phyllis Stark (April 21, 2001). "DreamWorks Nashville hits stride with Keith, Andrews". Billboard. p. 25.

- ^ Thom Owens. "Tennessee Plates". AllMusic. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Jeffrey B. Remz. "You and You Alone". Country Standard Time. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b L. Kent Wolgamott (May 1, 1998). "Getting back to their roots". Lincoln Journal Star. p. 20. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Jana Pendragon. "Tribute to Tradition". AllMusic. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Tim Brook (September 29, 2000). "Randy Travis rolls into town for concert". Journal and Courier. p. 10. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Lise Morgan (October 13, 2000). "Daddy-to-be Vince Gill plans light tour". Dayton Daily News. p. 29. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Jeffrey B. Remz (December 2000). "Randy Travis finds inspiration". Country Standard Time. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b c Todd Everett. "Inspirational Journey". AllMusic. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Mark Price (November 12, 2000). "Mysterious rhinestone cowboy to play the Palomino Club". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 10F. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 149-150.

- ^ a b c d "Dove Awards search". Dove Awards. Retrieved February 15, 2024. Enter "Randy Travis" in search box.

- ^ Alanna Nash (November 10, 2000). "Inspirational Journey". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ "Randy Travis may sing patriotic new single in O.C. at weekend concerts". The Los Angeles Times. October 3, 2001. p. F4. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ "Randy Travis stands with America". CMT. October 1, 2001. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 152-153.

- ^ a b Robert L. Doerschuk. "Rise and Shine". AllMusic. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Jeffrey B. Remz. "Rise and Shine review". Country Standard Time. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Mark Price (November 9, 2003). "Raise your glass to the top 40 drinkin' songs". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 5H. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Thom Jurek. "Worship & Faith". AllMusic. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b c Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "Passing Through". AllMusic. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ William Ruhlmann. "Bring It On". AllMusic. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Liana Jonas. "Tracy Lawrence". AllMusic. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Whitburn 2017, p. 53.

- ^ "19 years ago: Randy Travis receives a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame". The Boot. September 29, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2024.

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "Glory Train". AllMusic. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Nick Marino (October 25, 2005). "Randy Travis still covering sacred ground". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. pp. E12. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ "Randy Travis to sing inside cave at Carlsbad Caverns". Longview News-Journal. May 2, 2006. pp. 2A. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 160-161.

- ^ "Songs of the Season". AllMusic. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 165.

- ^ a b c d Jeff DeDekker (September 6, 2008). "Simpson's country debut a good effort". The Leader-Post. pp. B1. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Deborah Evans Price (July 28, 2008). "Randy Travis returns to country roots". The Leader-Post. pp. B3. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ "Randy Travis offers free download". Country Standard Time. March 11, 2008. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "Around the Bend". AllMusic. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "Carnival Ride". AllMusic. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ John Kiesewetter (March 17, 2009). "B105 DJ to see superstars perform his creation". The Cincinnati Enquirer. pp. A1. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Sterling Whitaker (March 18, 2017). "Remember when Carrie Underwood sang a duet with Randy Travis?". Taste of Country. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Whitburn 2017, pp. 365–366, 374–375.

- ^ "Randy Travis celebrates 25 years with friends". ABC 7. March 29, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c Karlie Justus. "Anniversary Celebration". Country Standard Time. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Jeffrey B. Remz. "Influence Vol. 1: The Man I Am". Country Standard Time. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c Cindy Watts (February 7, 2017). "Randy Travis: 'Damaged,' but still fighting after near fatal stroke". The Tennessean. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ "Rutgers cardiologist explains singer Randy Travis' heart disease". NJ.com. July 25, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Chris Talbott (July 11, 2013). "Singer Randy Travis suffers stroke". The Paducah Sun. pp. 3C. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Don Rauf (August 13, 2019). "Singer Randy Travis: Regaining His Voice — and His Life — After a Massive Stroke". Everyday Health. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Whitaker, Sterling (November 7, 2014). "Randy Travis' Fiancee Updates His Recovery". Tasteofcountry.com. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ Lorge, Melinda (August 4, 2023). "Randy Travis Is Preparing To Release A Brand New Album From The Vault: "It Has Already Been Mixed, Everything's Ready To Go"". Music Mayhem Magazine. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "Randy Travis Secretly Marries Mary Davis". ABC News. April 21, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Emily J. Shiffer (December 31, 2023). "Who Is Randy Travis' Wife? All About Mary Davis". People. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Watts, Cindy (March 29, 2016). "Randy Travis, Charlie Daniels, Fred Foster to be inducted to Country Music Hall of Fame". The Tennessean. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "30 Country Music Stars Join Forces for Historic CMA Music Video". ABC News. September 22, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Kruh, Nancy (June 2017). "Without Words, Randy Travis Makes Fans' Dreams Come True". People Country. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Hermanson, Wendy (May 5, 2019). "Randy Travis Celebrates 60th Birthday at Grand Ole Opry". Tasteofcountry.com. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ "For The First Time In Six Years, Randy Travis Is Going Back On Tour". Whiskeyriff.com. September 7, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Shakalis, Connie (July 14, 2023). "James Dupre performs with Randy Travis Band, and Travis, at Brown County Music Center". AOL. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Music of Randy Travis". maconcentreplex.org. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ Mims, Taylor (October 7, 2019). "Randy Travis cancelling most of 2019 tour due to production issues". Billboard. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ Brian Blair (July 6, 2023). "Country vocalist Dupre stands in for Randy Travis on tour". The Republic. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- ^ "Gaither Music Announces Randy Travis Precious Memories: Worship & Faith Album". Gaither. January 31, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ Moore, Bobby (July 21, 2020). "'Fool's Love Affair': The 38-Year History of Randy Travis' First Single Since 2013". Wide Open Country. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ "Randy Travis Announces First Album In Over A Decade, 'Where That Came From'". Whiskey Riff. May 1, 2024. Retrieved May 1, 2024.

- ^ Martin, Annie (May 3, 2024). "Randy Travis releases first song since 2013 stroke". UPI. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

- ^ "'CBS News Sunday Morning' gets an exclusive look inside the making of singer Randy Travis' new AI-created song". CBS News. May 3, 2024. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

- ^ Davis, Wes (May 5, 2024). "Randy Travis gets his voice back in a new Warner AI music experiment". The Verge. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 135-136.

- ^ Alanna Nash (March 6, 1998). "Ain't It the Truth". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 159.

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "Country State of Mind". AllMusic. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Cillea Houghton (February 9, 2017). "Country Stars Celebrate Randy Travis' 'Timeless' Legacy Backstage at Tribute Concert". Taste of Country. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ "Country music singer Travis stars in first TV special". Albuquerque Journal. August 25, 1993. pp. 4B. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, p. 128.

- ^ Sally Stone (November 30, 1995). "Randy Travis gets romantic". The Press Gazette. p. 15. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Jack Hurst (June 19, 1998). "Playing a terrible singer was strangely easy for Randy Travis". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Marcus K. Dowling. "Is that Randy Travis on 'The Price is Right'?". The Tennessean. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Becky Whitlock (October 16, 1992). "Marriage does not change country star". Kingsport Times-News. pp. 4D. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Michael Corcoran (August 24, 1993). "Common man Travis stars in first TV special Wednesday". The Day. pp. C3. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Travis & Abraham 2019, pp. 113–114.

- ^ "Randy Travis and wife-manager Elizabeth divorce". The Los Angeles Times. October 29, 2010. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Heller, Corine. "Randy Travis Arrested near Church, for Public Intoxication". Abc7.com. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ Moraski, Lauren (February 6, 2012). "Randy Travis arrested for public intoxication". CBS News. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ Martinez, Michael; Arioto, David (August 8, 2012). "Country singer Randy Travis arrested, accused of DWI". CNN. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (August 9, 2012). "Randy Travis arrested after trying to buy cigarettes while naked". The Guardian.

- ^ "Nude Travis demanded smokes?". August 13, 2012. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Video of Randy Travis' naked 2012 arrest released". ABC7 Chicago. December 5, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- Works cited

- Cusic, Don (1990). Randy Travis: The King of the New Country Traditionalists. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-04412-7.

- Travis, Randy; Abraham, Ken (2019). Forever and Ever, Amen: A Memoir of Music, Faith, and Braving the Storms of Life. Nelson Books. ISBN 978-1-4002-1483-9.

- Roland, Tom (1991). The Billboard Book of Number One Country Hits. Billboard Books. ISBN 0-8230-7553-2.

- Whitburn, Joel (2017). Hot Country Songs 1944 to 2017. Record Research, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89820-229-8.

External links

[edit]- Randy Travis at AllMusic

- Randy Travis at IMDb

- 1959 births

- 20th-century American guitarists

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century American male actors

- American baritones

- American country singer-songwriters

- American male singer-songwriters

- American country guitarists

- American acoustic guitarists

- American male guitarists

- Country Music Hall of Fame inductees

- Country musicians from North Carolina

- DreamWorks Records artists

- Grammy Award winners

- Grand Ole Opry members

- Living people

- People from Marshville, North Carolina

- Singer-songwriters from North Carolina

- Warner Records artists

- Word Records artists