Qesem cave

מערת קסם | |

| |

| Location | Central District, near the town of Kafr Qasim |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Periods | Lower Paleolithic |

Qesem cave is a Lower Paleolithic archaeological site near the town of Kafr Qasim in Israel. Early humans were occupying the site by 400,000 until c. 200,000 years ago.

The karstic cave attracted considerable attention in December 2010, when reports suggested Israeli and Spanish archaeologists had found the earliest evidence yet of modern humans. Science bloggers pointed out that the media coverage had inaccurately reflected the scientific report.[1]

Selective large-game hunting was regularly done followed by butchery of desired carcass parts for transport back to a residence for food sharing and cooking.

Description

[edit]

The cave exists in Turonian limestone in the western mountain ridge of Israel between the Samaria Hills and the Israeli coastal plain.[2][3] It is 90m above sea level and about 12 kilometers from the east coast of Mediterranean Sea.[4]

Deposits at the site are 7.5 m (25 ft) deep, and are divided into two layers: the upper is about 4.5 m (15 ft) thick, and the lower 3 m (10 ft). The upper forms a step on the lower one. The deposits contain stone tools and animal remains from the Acheulo-Yabrudian complex. This a period that follows after the Acheulian but before the Mousterian. No traces of Mousterian occupation have been found.[2][3]

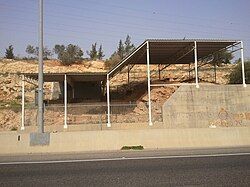

The cave was found in October 2000 when road construction destroyed its ceiling. This led to two rescue excavations in 2001. At present the site is protected, covered and fenced and subject to on-going excavations.[5]

Dating

[edit]Qesem Cave was occupied from about 420–220 ka,[6] although there is some uncertainty regarding the end date.[7] All archaeological finds at Qesem Cave have been assigned to the Acheulo-Yabrudian Cultural Complex (AYCC) of the late Lower Paleolithic.[8][9] In 2003, 230Th/234U dating on speleothems established the beginning of the occupation as "well before about 382,000 years ago."[2] Further research in 2010, 2013, and 2016, involved thermoluminescence dating (TL) on burnt flints and ESR/U-series (Electron spin resonance dating) on speleothems and herbivorous teeth.[10] [11] [7] As a result, the date for the start of the occupation has been revised to 420 ka.[12][13][14] The date for the end of the occupation has been problematic, with an early estimate of "before 152,000,"[2] subsequently revised to "between 220 and 194 ka" but rounded to "ca. 200 ka";[10] more recently "closer to 220 ka than to 194 ka"[7] and thus rounded to "220 ka."[6]

Artifacts

[edit]

Qesem Cave stone tools are made of flint. They are mainly blades, end scrapers, burins, and naturally backed knives. There are also flakes and hammerstones. Some of the horizons contain many blades and related blade-tools but they are absent in others. However thick side-scrapers are found throughout them. Acheulian type hand-axes are found at the top and at the bottom of the archaeological sequence. All stages of stone tool manufacture have been found. Many of the cores have sufficient of the surface cortex to allow reconstruction of the original stone's shape.[3] Stone tools of Qesem belong to 2 industries: Amudian (blades dominated) and Yabrudian (scraper dominated).[4]

Using the concentration of cosmic ray created Beryllium-10 it has been argued that the flint used at Qesem Cave was surface-collected or only dug from shallow quarries. This is in contrast to flint of the same period from Tabun Cave nearby that originated two or more metres below the surface, probably after being mined.[15]

A 2020 study led by researcher Ella Assaf from Tel Aviv University concluded that shaped stone balls discovered at Qesem cave were used to break the bones of large animals in order to extract the nutritious marrow inside.[16][17]

Fire

[edit]The Qesem Cave contains one of the earliest examples of regular use of fire in the Middle Pleistocene. Large quantities of burnt bone, defined by a combination of microscopic and macroscopic criteria, and moderately heated soil lumps suggest butchering and prey-defleshing occurred near fireplaces.

10–36% of identified bone specimens show signs of burning and on unidentified bone ones it could be up to 84%. Such heat reached 500 degrees C.[18]

A 300,000-year-old hearth was unearthed in a central part of the cave. Layers of ash was discovered in the pit, and burnt animal bones and flint tools used for carving meat were found near the hearth, suggesting it was used repeatedly and was a focal point for the people living there.[19]

"These were a very sophisticated, very clever people whose toolmaking was advanced, who hunted skillfully, could produce fire at will, and of course ate well, we believe it would have been a fairly small group of people staying here”, said Tel Aviv University archaeologist Ran Barkai.[20][4][21]

A 2020 study concluded that hominins living in Qesem cave managed to heat their flint to different temperatures before knapping it into different tools, for instance, blades were heated at 259 °C (498 °F) and flakes at 413 °C (775 °F) .[22]

Hunted prey

[edit]The faunal assemblages consist of 14 taxa.[21][4] Bones from 4,740 prey animals have been identified. These are mostly large mammals such as fallow deer (Dama, large-bodied form, 73–76% of identified specimens), aurochs (Bos), horse (Equus, caballine type), wild pig (Sus), wild goat, roe deer, wild ass and red deer (Cervus). Tortoise (Testudo) and a rare rhinoceros remains have also been found but no gazelle bones.[23]

These animal bones show marks of butchery, marrow extraction and burning from fire. Analysis of the orientation and anatomical placements of the cut marks suggest meat and connective tissue were cut off in a planned manner from the bone.[23]

Deer remains are limited to limb bones and head parts without remains of vertebrae, ribs, pelvis, or feet suggesting that butchery was selective in regard to the body parts that had been carried to the cave following initial butchery of the animal carcasses elsewhere.[23]

Moreover, the presence of fetal bones and the absence of deer antlers implies that much of the hunting took place in late winter through early summer. At that time the need for additional fat in the diet would have made those animals particularly important prey. The excavators described this as "prime-age-focused harvesting, a uniquely human predator–prey relationship".[23]

See also

[edit]- Archaeological sites in Israel

- Mugharet el-Zuttiyeh

- List of fossil sites

- Control of fire by early humans

- Skhul and Qafzeh hominins

References

[edit]- ^ Watzman, Haim (31 December 2010). "Human remains spark spat". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2010.700. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d Barkai R, Gopher A, Lauritzen SE, Frumkin A (June 2003). "Uranium series dates from Qesem Cave, Israel, and the end of the Lower Palaeolithic" (PDF). Nature. 423 (6943): 977–9. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..977B. doi:10.1038/nature01718. PMID 12827199. S2CID 4415446.

- ^ a b c Gopher A, Barkai R, Shimelmitz R, Khalaily M, Lemorini C, Heshkovitz I, et al., (2005). Qesem Cave: An Amudian Site in Central Israel. Journal of The Israel Prehistoric Society, 35:69-92

- ^ a b c d Hirst, K. Kris. "Qesem Cave - Middle and Lower Paleolithic Site in Israel". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- ^ Qesem Cave Project Excavations

- ^ a b Fornai, Cinzia; Benazzi, Stefano; Gopher, Avi; Barkai, Ran; Sarig, Rachel; Bookstein, Fred L.; Hershkovitz, Israel; Weber, Gerhard W. (2016). "The Qesem Cave hominin material (part 2): A morphometric analysis of dm2-QC2 deciduous lower second molar". Quaternary International. 398: 175–189. Bibcode:2016QuInt.398..175F. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.102. ISSN 1040-6182.

The Qesem Cave...site...has yielded...teeth associated to the...(AYCC) and dated to about 420-220 ka.

- ^ a b c Falguères, C.; Richard, M.; Tombret, O.; Shao, Q.; Bahain, J.J.; Gopher, A.; Barkai, R. (2016). "New ESR/U-series dates in Yabrudian and Amudian layers at Qesem Cave, Israel". Quaternary International. 398: 6–12. Bibcode:2016QuInt.398....6F. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.02.006. ISSN 1040-6182.

420-200 ka...closer to 220 ka.

- ^ Hershkovitz, Israel; Weber, Gerhard W.; Fornai, Cinzia; Gopher, Avi; Barkai, Ran; Slon, Viviane; Quam, Rolf; Gabet, Yankel; Sarig, Rachel (2016). "New Middle Pleistocene dental remains from Qesem Cave (Israel)". Quaternary International. 398: 148–158. Bibcode:2016QuInt.398..148H. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.059. ISSN 1040-6182.

All archaeological finds at Qesem Cave have been assigned to the Acheulo-Yabrusian Cultural Complex (AYCC) of the late Lower Paleolithic.

- ^ Assaf, Ella; Barkai, Ran; Gopher, Avi (2016). "Knowledge transmission and apprentice flint-knappers in the Acheulo-Yabrudian: A case study from Qesem Cave, Israel". Quaternary International. 398: 70–85. Bibcode:2016QuInt.398...70A. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.02.028. ISSN 1040-6182.

The site of Qesem Cave...consists of AYCC layers only.

- ^ a b Gopher, A.; Ayalon, A.; Bar-Matthews, M.; Barkai, R.; Frumkin, A.; Karkanas, P.; Shahack-Gross, R. (2010). "The chronology of the late Lower Paleolithic in the Levant based on U–Th ages of speleothems from Qesem Cave, Israel". Quaternary Geochronology. 5 (6): 644–656. Bibcode:2010QuGeo...5..644G. doi:10.1016/j.quageo.2010.03.003. ISSN 1871-1014.

- ^ Mercier, Norbert; Valladas, Hélène; Falguères, Christophe; Shao, Qingfeng; Gopher, Avi; Barkai, Ran; Bahain, Jean-Jacques; Vialettes, Laurence; Joron, Jean-Louis; Reyss, Jean-Louis (2013). "New datings of Amudian layers at Qesem Cave (Israel): results of TL applied to burnt flints and ESR/U-series to teeth". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (7): 3011–3020. Bibcode:2013JArSc..40.3011M. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.03.002. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ Parush, Yoni; Gopher, Avi; Barkai, Ran (2016). "Amudian versus Yabrudian under the rock shelf: A study of two lithic assemblages from Qesem Cave, Israel". Quaternary International. 398: 13–36. Bibcode:2016QuInt.398...13P. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.01.050. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ Barkai, Ran; Rosell, Jordi; Blasco, Ruth; Gopher, Avi (2017). "Fire for a Reason: Barbecue at Middle Pleistocene Qesem Cave, Israel". Current Anthropology. 58 (S16): S314 – S328. doi:10.1086/691211. ISSN 0011-3204. S2CID 148900875.

- ^ Weber, Gerhard W.; Fornai, Cinzia; Gopher, Avi; Barkai, Ran; Sarig, Rachel; Hershkovitz, Israel (2016). "The Qesem Cave hominin material (part 1): A morphometric analysis of the mandibular premolars and molar" (PDF). Quaternary International. 398: 159–174. Bibcode:2016QuInt.398..159W. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.027. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ Verri, G.; Barkai, R.; Bordeanu, C.; Gopher, A.; Hass, M.; Kaufman, A.; Kubik, P.; Montanari, E.; Paul, M.; Ronen, A.; Weiner, S.; Boaretto, E. (2004-05-17). "Flint mining in prehistory recorded by in situ -produced cosmogenic 10 Be". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (21): 7880–7884. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.7880V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402302101. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 419525. PMID 15148365.

- ^ Assaf, Ella; Caricola, Isabella; Gopher, Avi; Rosell, Jordi; Blasco, Ruth; Bar, Oded; Zilberman, Ezra; Lemorini, Cristina; Baena, Javier; Barkai, Ran; Cristiani, Emanuela (2020-04-09). "Shaped stone balls were used for bone marrow extraction at Lower Paleolithic Qesem Cave, Israel". PLOS ONE. 15 (4). Public Library of Science (PLoS): e0230972. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1530972A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230972. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7145020. PMID 32271815.

- ^ David, Ariel (2020-04-14). "Israeli Archaeologists Solve Mystery of Prehistoric Stone Balls". Haaretz. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- ^ Karkanas P, Shahack-Gross R, Ayalon A, et al. (August 2007). "Evidence for habitual use of fire at the end of the Lower Paleolithic: site-formation processes at Qesem Cave, Israel" (PDF). J. Hum. Evol. 53 (2): 197–212. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.04.002. PMID 17572475.

- ^ Gannon, Megan (2014-01-28). "Ancient Hearth Found In Israel Dates Back 300,000 Years, Scientists Say". Huffington Post. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ Blasco, R.; Rosell, J.; Arilla, M.; Margalida, A.; Villalba, D.; Gopher, A.; Barkai, R. (2019-10-01). "Bone marrow storage and delayed consumption at Middle Pleistocene Qesem Cave, Israel (420 to 200 ka)". Science Advances. 5 (10): eaav9822. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.9822B. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav9822. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6785254. PMID 31633015.

- ^ a b "Oldest Known Hearth Found in Israel Cave". National Geographic News. 2014-01-29. Archived from the original on May 9, 2020. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- ^ Agam, Aviad; Azuri, Ido; Pinkas, Iddo; Gopher, Avi; Natalio, Filipe (2020). "Estimating temperatures of heated Lower Palaeolithic flint artefacts" (PDF). Nature Human Behaviour. 5 (2): 221–228. doi:10.1038/s41562-020-00955-z. PMID 33020589. S2CID 222160202.

- ^ a b c d Stiner MC, Barkai R, Gopher A (July 2009). "Cooperative hunting and meat sharing 400–200 kya at Qesem Cave, Israel". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (32): 13207–12. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10613207S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900564106. PMC 2726383. PMID 19666542.

32°07′N 34°59′E / 32.11°N 34.98°E

External links

[edit]- Hardy, Karen; Radini, Anita; Buckley, Stephen; Sarig, Rachel; Copeland, Les; Gopher, Avi; Barkai, Ran (2016). "Dental calculus reveals potential respiratory irritants and ingestion of essential plant-based nutrients at Lower Palaeolithic Qesem Cave Israel". Quaternary International. 398: 129–135. Bibcode:2016QuInt.398..129H. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.04.033.